Note from August 1, 2020: After many years of relying on PageSpinner, RSRF has yielded at last to the march of Macintosh operating systems. From now on, all pages and all revisions to pages will be done with Abode DreamWeaver. Eventually..., this will allow us to make them look better...

Since 1997, the Red Saunders Research Foundation has been dedicated to increasing our knowledge of the musicians who filled the clubs and recording studios of Chicago with great music during the two decades after World War II.

Here is how Jack Tracy—who wrote for Down Beat, then became the editor, then produced jazz LPs for Argo and Mercury—described the scene (Steven Cerra, "Jack Tracy, 1927-2010 — Remembering an Old Friend," http://jazzprofiles.blogspot.com/2013/07/jack-tracy-1927-2010-remembering-old.html ):

Live music? Any night of any week you wanted to hear jazz there were at least two dozen places you could go to hear swing, bebop, Dixieland, mainstream jazz, excellent singers—take your pick. There’d be big names and big bands at the Chicago Theater, the Regal and the Oriental, and seemingly everywhere local talent waiting to break out nationally. You’d hear them at any of the many local bars and restaurants that would sporadically give music a try. A number of smaller local clubs made jazz their steady policy. [...]

The South Side, Chicago’s vast black community, was like a city unto itself. Places with live music abounded, and on the bandstands would be performers as varied as Gene Ammons, Muddy Waters, Lurlean Hunter, Frank Strozier, Willie Dixon, Von Freeman, Sun Ra, Jody Christian, Joe Williams, Tom Archia and John Young, plus the likes of stars such as Charlie Parker, Dinah Washington, Sonny Stitt, Cannonball Adderley and Miles Davis at clubs like the Bee Hive and the Sutherland Lounge.

So many names, such marvelous music and so many venues, all gone now but with echoes that can still be faintly heard if you close your eyes and listen very closely.

You should have been there.

Some musicians from Chicago were appreciated by the fans early on, like Gene Ammons and Johnny Griffin—yet their full worth only gradually become apparent to the writers over the years. Others were not widely recognized until much later in their careers, like John Gilmore, Clifford Jordan, Norman Simmons, or Muhal Richard Abrams. Far too many others have been forgotten.

There are two reasons for this neglect of Chicago musicians from the postwar period:

One is that most jazz writing has focused on New York or on the West Coast. Some attention has been paid to Chicago in the 1920s, but much less to the 1930s and virtually none to the period after World War II. Such a bias is still apparent in the work of older American jazz critics.

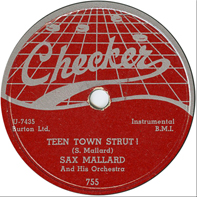

The other is that in Chicago, the boundaries between jazz and other forms of Great Black Music were highly permeable; the same individuals moved from jobs in jazz combos, to society band gigs, to dates with bar-walking R&B players. Andrew Hill could play adventurous jazz one night, back a doo-wop group the next, work a cocktail lounge the next. Tenor player Harold Ousley could rehearse with Sun Ra's experimental band, then turn in a set of R&B with King Kolax at the Crown Propeller Lounge. Sax Mallard, who once sat next to Johnny Hodges in Duke Ellington's reed section, might end up honking behind the Coronets, Mitzi Mars, or Roosevelt Sykes.

Until 1955 or so, R&B was not sharply distinguished from jazz, and R&B recordings were reviewed in jazz publications. But the rise of rock and roll led to a preoccupation with demarcating jazz from other, more "popular" forms of music, so it would get the respect owed to "serious music." Performers on the borderline between jazz and R&B, jazz and blues, jazz and rock and roll, were automatically suspect. It is only since around 1990 that the sharp boundaries have again come into question.

We dedicate this Web page to the memory of Vernel Fournier (1928-2000), Richie Dell Archia-Thomas (1922-2001), and Marv Taman (1948-2011).

The members of the Red Saunders Research Foundation are

- Len Bukowski, Florida Bureau (email: lenniBukowski aTaol DoT com)

- Armin Büttner, Zürich Bureau (email: abuettner At woz dOt ch)

- Robert L. Campbell, Clemson Bureau (email: campber aT clemson Dot edu)

- Bill Daniels, New Hampshire Bureau (email: billdani At comcast DoT net)

- Stephen Dikovics, New York City Bureau (email: flapsafterhours aT aol DoT com)

- Daniel Gugolz, Vienna Bureau (email: danielmgugolz aT gmx dOt at)

- John Holley, Mudford Bureau

- Tom Kelly, St. Louis Bureau (email: tomkellyarchives At aol Dot com)

- Dan Kochakian, Florida Bureau (email: danrandb At gmail Dot com)

- Big Joe Louis, London Bureau (email: louis Dot music aT virgin doT net)

- Mark Mumea, San Pedro, CA Bureau (email: mark aT devilstalemusic doT com)

- Konrad Nowakowski, Vienna Bureau (email: k doT nowakowski At tirol Dot com)

- Jim O'Neal, Kansas City Bureau (email: bluesoterica At aoL DoT com)

- Victor Pearlin, Worcester, MA Bureau (email: VPearlin At aol Dot com)

- Robert Pruter, Chicago Bureau (email: pruter aT comcast Dot net)

- Bill Sabis, Gainesville, Florida Bureau (email: bilsab At bellsouth Dot net)

- Yves François Smierciak, Chicago Bureau (email: rocambujazz At yahoo Dot com)

- Dr. Robert Stallworth, Nevada Bureau (email: robertstallworth aT aol dOt com)

- Helge Thygesen, Svendborg Bureau (email: patton aT mail doT dk)

- Chris Trent, Burrough on the Hill, UK Bureau (email: cdt AT calundronius DOT co DoT uk)

- Billy Vera, Los Angeles Bureau (email: billyvera At ca Dot rr dOt com)

- George R. White, York Bureau (email: music dOt mentor aT lineone doT net)

- Art Zimmerman, Jericho, New York Bureau (email: zimrecords At msn Dot com)

One of our founding members, Otto Flückiger, died on March 7, 2006. He was 76 years old. It was partly at Otto's urging that we started RSRF in 1997. One of our first two pages, on Tom Archia, we undertook because of Otto's unflagging commitment to an artist he believed had been unfairly neglected. Without Otto's years of efforts to document the music and his generous assistance with press clippings, label scans, and dubs of 78s from his collection, our pages would be much the poorer.

On November 15, 2014, we lost the great postwar blues record collector, George Paulus, who was 66. Also active in recording blues artists (and in preserving and reissuing historic recordings), George did a lot to improve many parts of this site over the years. Without his encouragement we would never have taken up the incredibly obscure and confusing Mayo Williams labels, and without George we would neither have a page on OraNelle—nor be able to hear most of the sides that were made in Bernard Abrams' store.

We lost another long-time member, Ferdie Gonzalez, the great vocal group discographer, on October 24, 2020.

We have received invaluable assistance from Robin Archia, Tom Ball, Anthony Barnett, Bob Buchholz, Nadine Cohodas, John Corbett, Chris DeVito, Ken Ellzey, Robert Ferlingere, Dan Ferone, the late Vernel Fournier, Peter Gibbon, Marv Goldberg, Brian Neal Green, Ronnie Haig, Alvin Hubert, Robert Javors, Shirley Klett, Bob Koester, the late Eric LeBlanc, John McCarthy, Sarah McLawler, Dave Penny, Bob Porter, Howard Rye, Dave Sax, the late Seymour Schwartz, Frank Scott, Joseph Nathan Scott, the late Marv Taman, the late Richie Dell Thomas, the late Charles Walton, Johnnie Mae Walton, Lucius Washington, and Stefan Wirz.

Our special thanks go to Richard Schwegal, music librarian of the Chicago Public Library, who has provided us access to the Chicago Federation of Musicians Member Death Files 1940-1979.

Abco was a small label, in operation just from February through August 1956. It was jointly owned by Joe Brown of JOB Records and Eli Toscano (born 1924) of A. B.'s One Stop; the company was housed in Toscano's premises at 2854 Roosevelt Road, while Joe Brown's Lawn Music handled the publishing. All Abcos were recorded at Universal, with high-quality sonic results. The company's first session, in February, was split between a well-known blues performer, Arbee Stidham, and an extremely obscure one who went as Herby Joe. The next, in March, was a jazz outing by an all-star group led by drummer Allan Williams, who recorded it under his calypso handle, Zono Sago. The band included Lucius Washington on tenor saxophone. Freddie Hall then laid down two two hard-rocking sides with Louis and Dave Myers' band, the Aces, and the Aces followed up with their own session, featuring Louis Myers on harmonica. In May Abco recorded the doowop group the Rip Chords (formerly the Knights of Rhythm) and bluesman Morris Pejoe with a studio band that featured Wayne Bennett (most likely) on lead guitar. The final session, in June, was Arbee Stidham's again; on this occasion he was accompanied by Wayne Bennett on lead guitar and, on one memorable side, Walter Horton playing double-tracked harmonica. Joe Brown also tried to sneak in a reissue of a JOB single from 1953, by Floyd Jones, but it appears that this was quickly withdrawn and replaced with the Freddie Hall. On July 11, Abco recorded four different artists, including bluesman Otis Rush, but by August, Abco had broken up. Toscano and a new business partner, Howard Bedno, launched Cobra Records and put the July 11 material out in September, while Joe Brown returned to JOB. Abco ended up responsible for just 9 releases, but these are nearly all top-quality music of the period. [Revised 2/26/2020]

One of our first projects was a discography of the forgotten Texas tenor, Tom Archia, who was born in Groveton, Texas in 1919, and raised in the Houston area. Although he grew up with Illinois Jacquet and Arnett Cobb, Archia modeled his style after Lester Young rather than Coleman Hawkins. Archia was a major contributor in Chicago from 1942, when he arrived in town with Milt Larkin's band, until he left the city in 1967, but his recording career was unfortunately a good deal shorter. All of his known appearances on record took place between 1943 and 1960, and the bulk of his work was compressed into just two years: 1947-1948. As the headliner at Leonard Chess's club, the Macomba Lounge, he was featured on the Aristocrat label before its financial future was assured by the rise of Muddy Waters. The appearance in 2001 of Tom Archia 1947-1948 (Classics 5006) made many of his Aristocrat recordings as a leader available for the first time in over 50 years; the 2002 release of Andrew Tibbs 1947-1951 (Classics 5028) puts two more sessions back in the light of day; only his session with Armand "Jump" Jackson awaits proper reissue. While a few items with Wynonie Harris have been renowned for years, some of his work with Hot Lips Page for King Records waited until 1999 to be issued, and some high-quality unreleased items with Wynonie Harris all the way to 2015. In 1952 Archia made an unannounced appearance on a session by Dinah Washington and another one on a session by blues singer Gates White; he probably also worked with Dinah Washington on a session from early 1953. He made another unheralded appearance behind the doowop group The Larks for Chess in 1959. His final recording session was a special Blues Party organized by Jump Jackson for William Claxton and Joachim Ernst Berendt in the summer of 1960; the artists included Sunnyland Slim, Roosevelt Sykes, Shakey Jake, Lee Jackson, and Eddie Clearwater, and at least 25 sides were made, 10 of which included Archia's tenor sax. Two sides from the party were included with Berendt and Claxton's book Jazz Life, which was published in Germany in 1961, but none of the material has ever been commercially released. Gigs became scarcer in the 1960s, and in 1967, Tom Archia returned to Houston to recuperate from a broken jaw. When he was able to play again, he rehearsed with Houston-area bands and took such gigs as were available for jazz musicians during those years. Tom Archia died of cancer in 1977; he was given a proper jazz funeral in Houston's Third Ward. With the help of his sister, the late Richie Dell Thomas, his daughter, Robin Archia, and his cousin, Johnnie Mae Walton, we have been able to provide the first biography of Tom Archia.[Last updated 5/17/2024]

The Aristocrat label was the predecessor of Chess Records. Aristocrat has often been assimilated to Chess, even though it had different owners and a different approach to recording and selling music. The company was founded by Charles and Evelyn Aron in April 1947. From June through December 1947, talent scout Sammy Goldberg helped to orient the new company toward rhythm and blues; he brought Jump Jackson, Tom Archia, Clarence Samuels, Andrew Tibbs, and Sunnyland Slim to the label. Leonard Chess, whose business at the time was running the Macomba Lounge, did not become involved with the new company until September 1947; his initial role was strictly as a salesman. During the company's first year of operation, Sunnyland Slim and a guitarist Slim brought to his first session, Muddy Waters, were the label's only down-home blue artists. The most-recorded musician during 1947 was Lee Monti, who led a polka band with two accordions; the second and third-most recorded artists were jazz tenor saxophonist Tom Archia and uptown blues singer Andrew Tibbs. In the early going, the company also recorded the piano trios of Prince Cooper, Duke Groner, and Jimmie Bell, ballad singer Danny Knight and crooner Jerry Abbott, and a gospel group called the Seven Melody Men; it even tried out Country and Western guitarist Dick Hiorns. When Muddy Waters scored a hit with "I Can't Be Satisfied" in June 1948, the label's orientation began to shift, but Andrew Tibbs was the company's top seller well into 1949. The dual emphasis on jazz (Gene Ammons) and down-home blues (Muddy Waters, Robert Nighthawk, The Blues Rockers) wasn't fully established until the first half of 1950, after the Chess brothers had bought out Evelyn Aron's remaining share of the company.

The Aristocrat label was the predecessor of Chess Records. Aristocrat has often been assimilated to Chess, even though it had different owners and a different approach to recording and selling music. The company was founded by Charles and Evelyn Aron in April 1947. From June through December 1947, talent scout Sammy Goldberg helped to orient the new company toward rhythm and blues; he brought Jump Jackson, Tom Archia, Clarence Samuels, Andrew Tibbs, and Sunnyland Slim to the label. Leonard Chess, whose business at the time was running the Macomba Lounge, did not become involved with the new company until September 1947; his initial role was strictly as a salesman. During the company's first year of operation, Sunnyland Slim and a guitarist Slim brought to his first session, Muddy Waters, were the label's only down-home blue artists. The most-recorded musician during 1947 was Lee Monti, who led a polka band with two accordions; the second and third-most recorded artists were jazz tenor saxophonist Tom Archia and uptown blues singer Andrew Tibbs. In the early going, the company also recorded the piano trios of Prince Cooper, Duke Groner, and Jimmie Bell, ballad singer Danny Knight and crooner Jerry Abbott, and a gospel group called the Seven Melody Men; it even tried out Country and Western guitarist Dick Hiorns. When Muddy Waters scored a hit with "I Can't Be Satisfied" in June 1948, the label's orientation began to shift, but Andrew Tibbs was the company's top seller well into 1949. The dual emphasis on jazz (Gene Ammons) and down-home blues (Muddy Waters, Robert Nighthawk, The Blues Rockers) wasn't fully established until the first half of 1950, after the Chess brothers had bought out Evelyn Aron's remaining share of the company.

"The Aristocrat of Records" was in operation from April 1947 until June 3, 1950, when Leonard and Phil Chess, who now owned 100% of it, officially changed the name of the label. (The kept the name for the distribution side of their operation.) Aristocrat recorded something like 271 tracks, purchased 28 more, and put out at least 94 releases (187 sides, since one was used twice). But pressing runs were short, sales on most were poor, and company documentation was scanty. What's more, the enterprise wasn't above a certain amount of subterfuge, issuing 6 live broadcast items from the first half of 1948 with bogus matrix numbers, crediting two of them to a phony bandleader. We have compiled a detailed history and a complete discography of the label. This is the most complete and accurate treatment of Aristocrat available anywhere. It includes label scans from many rare Aristocrat issues. We are eager to hear from collectors who might have additions and corrections. [Last updated 11/6/2022]

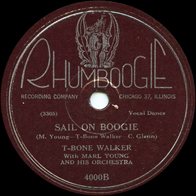

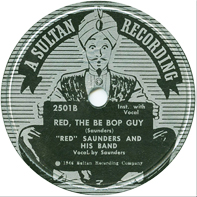

Buster "Leap Frog" Bennett (1914-1980) was born James Joseph Bennett in Pensacola, Florida. He became a professional musician at a young age, and was already performing on the road in Texas around 1930. He arrived in Chicago in the summer of 1938, first appearing on record in September of that year. He quickly became a top sideman for the Melrose combine in Chicago, working in the studio with Big Bill Broonzy, Jimmie Gordon, Merline Johnson (The Yas Yas Girl), Ramona Hicks, Jimmy McLain, Minnie Mathes, and Monkey Joe. His most fruitful association, however, was with Washboard Sam; he played on Sam's big hit "Diggin' My Potatoes" and many other sides. He began leading a trio in the Chicago clubs in 1941; despite recurring health problems, an incorrigible habit of tapping club owners for advances on his salary, and a fiery temper (he once got into a fistfight with a Union Board member during a meeting), he was sought out by club owners who valued his ability to bring in customers every night. For the next decade Buster sang and played alto, soprano, and tenor saxes as the leader of his own band. (He snuck in some piano and string bass as well.) His tight, very musical combos had the good fortune to cut 24 sides for Columbia over a three-year period. In addition, he made clandestine appearances on Rhumboogie (on a session nominally led by his trumpet player, Charles Gray), with the Red Saunders combo on Sultan, with Tom Archia's combo on Aristocrat, and with a quartet nominally led by his bassist, Israel Crosby, on a session that was picked up by Apollo. Though on the road for long periods from 1948 through 1950, he continued to work Chicago clubs until 1954, after which he dropped completely off the scene. He had had bouts with tuberculosis in 1941 and again in 1942-1943; it appears that he moved to Texas after developing further health problems that interfered with his playing. While record companies saw commercial potential in Buster's blues vocalizing, nightclub patrons also wanted him to sing standards (the "Buster Bennett Medley" is the only recorded evidence of his ballad side). The personnel of his different recording bands is still imperfectly known, but at different times he used Willie Jones (1920-1977) and Wild Bill Davis (1918-1995) on piano, Duke Groner (1908-1992) and Israel Crosby (1919-1962) on bass, Charles Gray (1918-1995), Harry "Pee Wee" Jackson (c. 1916-1954), and Fip Ricard (1923-1996) on trumpet, and Andrew "Goon" Gardner (1916-1975) on alto sax. Buster Bennett died in total obscurity in Houston, Texas; he had probably been away from music for a quarter century. In 2002, the first (and so far only) comprehensive reissue package of Buster's work as a leader appeared on Classics 5037.[Last updated 5/26/2021]

Buster "Leap Frog" Bennett (1914-1980) was born James Joseph Bennett in Pensacola, Florida. He became a professional musician at a young age, and was already performing on the road in Texas around 1930. He arrived in Chicago in the summer of 1938, first appearing on record in September of that year. He quickly became a top sideman for the Melrose combine in Chicago, working in the studio with Big Bill Broonzy, Jimmie Gordon, Merline Johnson (The Yas Yas Girl), Ramona Hicks, Jimmy McLain, Minnie Mathes, and Monkey Joe. His most fruitful association, however, was with Washboard Sam; he played on Sam's big hit "Diggin' My Potatoes" and many other sides. He began leading a trio in the Chicago clubs in 1941; despite recurring health problems, an incorrigible habit of tapping club owners for advances on his salary, and a fiery temper (he once got into a fistfight with a Union Board member during a meeting), he was sought out by club owners who valued his ability to bring in customers every night. For the next decade Buster sang and played alto, soprano, and tenor saxes as the leader of his own band. (He snuck in some piano and string bass as well.) His tight, very musical combos had the good fortune to cut 24 sides for Columbia over a three-year period. In addition, he made clandestine appearances on Rhumboogie (on a session nominally led by his trumpet player, Charles Gray), with the Red Saunders combo on Sultan, with Tom Archia's combo on Aristocrat, and with a quartet nominally led by his bassist, Israel Crosby, on a session that was picked up by Apollo. Though on the road for long periods from 1948 through 1950, he continued to work Chicago clubs until 1954, after which he dropped completely off the scene. He had had bouts with tuberculosis in 1941 and again in 1942-1943; it appears that he moved to Texas after developing further health problems that interfered with his playing. While record companies saw commercial potential in Buster's blues vocalizing, nightclub patrons also wanted him to sing standards (the "Buster Bennett Medley" is the only recorded evidence of his ballad side). The personnel of his different recording bands is still imperfectly known, but at different times he used Willie Jones (1920-1977) and Wild Bill Davis (1918-1995) on piano, Duke Groner (1908-1992) and Israel Crosby (1919-1962) on bass, Charles Gray (1918-1995), Harry "Pee Wee" Jackson (c. 1916-1954), and Fip Ricard (1923-1996) on trumpet, and Andrew "Goon" Gardner (1916-1975) on alto sax. Buster Bennett died in total obscurity in Houston, Texas; he had probably been away from music for a quarter century. In 2002, the first (and so far only) comprehensive reissue package of Buster's work as a leader appeared on Classics 5037.[Last updated 5/26/2021]

The Four Blazes began life as a vocal/string ensemble in 1940; the next year, they acquired their lead guitarist Floyd McDaniel (1915-1995). In 1945 they bulked up to Five Blazes by adding Ernie Harper's piano; this ensemble cut four sides for Aristocrat in April 1947, including the estimable "Chicago Boogie" and "All My Geets Are Gone." They downsized to Four Blazes in 1948, after Harper decided to go solo; he worked regularly in the Chicago clubs through the mid-1950s. After Prentice Butler died, the Four Blazes hired a bassist from Chattanooga, Tennessee, named Tommy Braden. Braden, who joined them in 1951, brought a distinctive lead vocal style to the group. The Blazes recorded a series of singles for United from 1952 to 1955. Their first release, "Mary Jo," hit #1 on the R&B charts, and three others reached the top 10. Braden became restless and went solo for a while in 1954, and the group broke up for good in 1955. Floyd McDaniel, drummer Paul Lindsley "Jelly" Holt (who remained with the Blazes from beginning to end) and bassist and lead vocalist Braden (who died in 1957) were all significant contributors to the R&B scene in Chicago. The group's United sides also benefited from excellent tenor saxophone work by guest artists Eddie Chamblee (1920 - 1999) and Red Holloway (1927 - 2012). Our page adds an up-to-date appendix on a Hollywood-based group that also called itself the Four Blazes, and even performed a "Chicago Boogie" and a "Chicago Blues." The Hollywood group, which recorded from 1944 through 1948, has sometimes been confused with the Chicago group on reissues. The Chicago group has been fairly well served in that regard; Delmark has put all of the Blazes' United tracks on CD. The Hollywood group could still use some attention. [Last updated 7/9/2013]

Boxer was a boutique label that operated in 1959 and 1960, toward the end of the RSRF time frame. It was started by Johnny Moore, a former janitor at Englewood High School who had discovered the vocal group The El Dorados singing in the hallway, became their manager, and in 1954 got them signed to Vee-Jay. The first act he recorded for Boxer, Jesse and the Sequins, was also a vocal group, but the other artists on his short roster were blues, soul, jazz, and novelty performers. The first Boxer session, in April 1959, featured Jesse Blackful (a drummer and vocalist) and the Sequins (a girl group), all of whom were from Battle Creek, Michigan. First-class accompaniment was provided by a Lefty Bates combo. Boxer 201 featured the entire lineup, while 203 was reserved to Bates and the Sequins. Moore next signed bluesman Bobo Jenkins (1916-1984), who was based in Detroit and had previously recorded for J V B, Chess, and Fortune. Jenkins recorded four sides with backing from guitarists Willie Johnson and Eddie Taylor and drummer Earl Phillips; two saw release on Boxer 202. Six months later, Boxer 204 was the work of rising soul singer McKinley Mitchell (1934-1986), making his recording debut with a rocking blues band (Willie Johnson again on lead guitar). Mitchell's next record, done for One-derful in 1962, would be a national hit. In September 1960, Moore cut a session featuring Harold Harris (1934- ), a jazz pianist he had discovered who recorded with a trio. There was a briefly available Harris single on Boxer 110. Boxer 111, by the eccentric singer Russell Taplin aka Saxie Russell, brought the label's run to an end. After 18 months, Moore's recording activity had exhausted his funds; however, he was able to sell the Jesse and the Sequins single to Mel London, who reissued it on his Profile label. And when Harold Harris signed with Vee-Jay, recording more than an album's worth of material in February 1961, Vee-Jay also bought his Boxer sides, though just one reissue (on the Japanese P-Vine label in 1998) has made further use of them. The Boxer legacy thus consists of six obscure singles and a few unissued tracks, all deserving of a coordinated reissue.[Revised 7/13/2020]

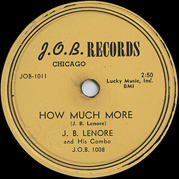

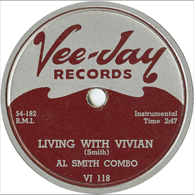

The Chance label was in business from August 1950 through December 1954. It was opened by Art Sheridan, who knew the record business from operating a pressing plant and a distributorship. Chance was unable to make new recordings for several months (August 1951 through early 1952) because of major trouble with the Musicians Union, but it bounced back and picked up Ewart Abner, Jr., who handled its accounting, in 1952. Despite wide-ranging activity in 1953, the label wound down in 1954, doing most of its final year's recording in January and February. It closed up shop at the end of the year when Abner moved over to Vee-Jay, where Sheridan became a silent partner. Chance recorded blues, doo-wop, R&B, gospel, pop, a little bit of country and western, and a fair amount of jazz (some of which has never been listed in any jazz discographies). In all, Chance recorded 360 sides and leased or purchased another 44 during its lifetime; there are 93 known issues on the Chance label, 1 on its ephemeral, nearly unknown Meteor subsidiary, and 9 on a more durable spinoff called Sabre. The blues, jazz, and R&B appeared on the main Chance 1100 series, to which a 5000 series for gospel and a 3000 series for pop were added later. Originally a 78-only label, Chance did not embrace the 45-rpm format till the fall of 1952, and never did get around to it for its gospel series. Major acts for Chance included The Moonglows, The Flamingos, Homesick James Williamson, J. B. Hutto, Bobby Prince, John Sellers, and John "Schoolboy" Porter; Chance's collaboration with JOB resulted in classic blues recordings by Johnny Shines, J. B. Lenoir, Big Boy Spires, and Little Hudson. Initially Schoolboy Porter and Wally Hayes ran the house bands; after it recovered from its union trouble and Schoolboy Porter joined the Air Force, the company relied heavily on Al Smith, with King Kolax or Red Holloway occasionally taking over the studio chores. The gospel series included classic sides by The Golden Tones and Sister Rosa Shaw. The pop series draws less interest today, though Jack Teter was a unique artist, Eddie Bracken had a long career on stage, Lucy Reed and Ann Gilbert were jazz singers of note (though they did not get the opportunity to record jazz for Chance), the Meadowlarks were an extremely capable vocal group, Eddie and Chuck were early rockabilly artists, and Remo Biondi made his unique creative contributions to two of the pop-series releases. [Latest update 3/30/2024]

The Chance label was in business from August 1950 through December 1954. It was opened by Art Sheridan, who knew the record business from operating a pressing plant and a distributorship. Chance was unable to make new recordings for several months (August 1951 through early 1952) because of major trouble with the Musicians Union, but it bounced back and picked up Ewart Abner, Jr., who handled its accounting, in 1952. Despite wide-ranging activity in 1953, the label wound down in 1954, doing most of its final year's recording in January and February. It closed up shop at the end of the year when Abner moved over to Vee-Jay, where Sheridan became a silent partner. Chance recorded blues, doo-wop, R&B, gospel, pop, a little bit of country and western, and a fair amount of jazz (some of which has never been listed in any jazz discographies). In all, Chance recorded 360 sides and leased or purchased another 44 during its lifetime; there are 93 known issues on the Chance label, 1 on its ephemeral, nearly unknown Meteor subsidiary, and 9 on a more durable spinoff called Sabre. The blues, jazz, and R&B appeared on the main Chance 1100 series, to which a 5000 series for gospel and a 3000 series for pop were added later. Originally a 78-only label, Chance did not embrace the 45-rpm format till the fall of 1952, and never did get around to it for its gospel series. Major acts for Chance included The Moonglows, The Flamingos, Homesick James Williamson, J. B. Hutto, Bobby Prince, John Sellers, and John "Schoolboy" Porter; Chance's collaboration with JOB resulted in classic blues recordings by Johnny Shines, J. B. Lenoir, Big Boy Spires, and Little Hudson. Initially Schoolboy Porter and Wally Hayes ran the house bands; after it recovered from its union trouble and Schoolboy Porter joined the Air Force, the company relied heavily on Al Smith, with King Kolax or Red Holloway occasionally taking over the studio chores. The gospel series included classic sides by The Golden Tones and Sister Rosa Shaw. The pop series draws less interest today, though Jack Teter was a unique artist, Eddie Bracken had a long career on stage, Lucy Reed and Ann Gilbert were jazz singers of note (though they did not get the opportunity to record jazz for Chance), the Meadowlarks were an extremely capable vocal group, Eddie and Chuck were early rockabilly artists, and Remo Biondi made his unique creative contributions to two of the pop-series releases. [Latest update 3/30/2024]

We held off covering Chess Part I in the past, because the Chess and Checker labels had been better documented than most of the companies covered here. Part I sketches the company's activities over its first two and a half years in business, from June 3, 1950, when Leonard and Phil Chess changed its name from Aristocrat, to the end of 1952. This was a period of considerable expansion (which led, in April 1952, to the opening of a new subsidiary called Checker). Even in 1952, money was tight: the combined Chess and Checker operation was still not recording as many sides per year in Chicago as its ancestor had in 1947, though it was aggressively buying material from other producers. In its first three years, Chess solidified its position in the down-home blues field with many releases by Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf; in 1952, Little Walter became a successful headliner as well, leaving Muddy Waters' band as soon as his first release became a hit. In February 1951, Chess got Al Hibbler sides from the defunct Sunrise operation, which brought in considerable revenue that year. At the end of 1951, Chess bought up most of the remains of Premium, including unsold pressings that were rebranded with Chess labels. In the fall of 1951 the company also dipped its toe into the emerging market for 7-inch 45s, slowly increasing the frequency of 45 rpm releases in 1952.

We held off covering Chess Part I in the past, because the Chess and Checker labels had been better documented than most of the companies covered here. Part I sketches the company's activities over its first two and a half years in business, from June 3, 1950, when Leonard and Phil Chess changed its name from Aristocrat, to the end of 1952. This was a period of considerable expansion (which led, in April 1952, to the opening of a new subsidiary called Checker). Even in 1952, money was tight: the combined Chess and Checker operation was still not recording as many sides per year in Chicago as its ancestor had in 1947, though it was aggressively buying material from other producers. In its first three years, Chess solidified its position in the down-home blues field with many releases by Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf; in 1952, Little Walter became a successful headliner as well, leaving Muddy Waters' band as soon as his first release became a hit. In February 1951, Chess got Al Hibbler sides from the defunct Sunrise operation, which brought in considerable revenue that year. At the end of 1951, Chess bought up most of the remains of Premium, including unsold pressings that were rebranded with Chess labels. In the fall of 1951 the company also dipped its toe into the emerging market for 7-inch 45s, slowly increasing the frequency of 45 rpm releases in 1952.

During 1951 and 1952, the Chess brothers were also heavily dependent on Sam Phillips' emerging recording operation in Memphis, which supplied them with blues, R&B, gospel, even a little bit of hillbilly. There was limited vocal-group activity during this period (just one session by The Dozier Boys, a session by the Bayou Boys, two sessions by the Coronets, and purchased sessions by the Clefs and the Encores). In the jazz department, Gene Ammons recorded extensively in 1950 and 1951; Claude McLin had a hit in 1950 but the label dropped him when he left Chicago at the beginning of 1952; Eddie Johnson got the sales push in 1951 and 1952, but dropped off the roster when he became ill in 1953. We have been able to shine additional light on the early Chess years, but additions and corrections are still needed and will be appreciated. [Revised 3/7/2024]

During 1951 and 1952, the Chess brothers were also heavily dependent on Sam Phillips' emerging recording operation in Memphis, which supplied them with blues, R&B, gospel, even a little bit of hillbilly. There was limited vocal-group activity during this period (just one session by The Dozier Boys, a session by the Bayou Boys, two sessions by the Coronets, and purchased sessions by the Clefs and the Encores). In the jazz department, Gene Ammons recorded extensively in 1950 and 1951; Claude McLin had a hit in 1950 but the label dropped him when he left Chicago at the beginning of 1952; Eddie Johnson got the sales push in 1951 and 1952, but dropped off the roster when he became ill in 1953. We have been able to shine additional light on the early Chess years, but additions and corrections are still needed and will be appreciated. [Revised 3/7/2024]

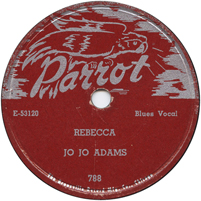

Our history of Chess Part II covers the years 1953 to 1955. During this period the Chess and Checker labels enjoyed a series of best sellers by Muddy Waters and Little Walter in the downhome blues field, and 1955 was the label's breakthrough year in rock and roll: both Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley made their debuts. Increased cash flow enabled the Chess brothers to invest more heavily in studio sessions, which were still being done primarily at Universal Recording in Chicago, and to purchase material from a variety of outside sources. The arrangement with Sam Phillips in Memphis came to an end in early 1953. The last Memphis-based Chess artist, Howlin' Wolf, had to be recorded in Lester Bihari's makeshift studio until the Chess brothers could prevail upon him to move to Chicago in early 1954. However, associations with Paul Gayten in New Orleans and some other suppliers proved fruitful, as did the collapse of Swing Time Records, which left Lowell Fulson available for signing. By 1955, the company was 100% invested in 45s; Chess 1603 was the last 78-only release. At the very end of this period, the company was gearing up to launch a third label, Marterry (the name was changed to Argo after just two releases on singles and one on LP). The Chess brothers were also succumbing to the inevitable onset of the 12-inch LP. In other genres, Chess and Checker recorded many other blues artists, released a few jazz items. and remained fairly active in gospel. While most of the Chess and Checker doowop acts remained obscure, the company had the good fortune to buy out the Moonglows' contract with Chance in late 1954, then picked the Flamingos up in 1955 as Parrot began to falter. There was even a 9 month venture into Country music, with a soupçon of rockabilly: the Chess 4858 series of 1954-1955, produced by Stan Lewis in Shreveport, Louisiana. [Revised 5/27/2024]

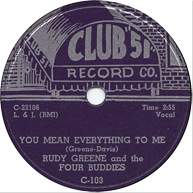

The Club 51 label was a side business for local roller skating impresario and record store owner Jimmie Davis. Davis operated the label from March 1955 to some point in 1957. In all there were just 7 releases on Club 51 (three other records that we know of were given limited circulation on test pressings but not actually released). The label's artist roster consisted of two doo-wop groups (the "Four" Buddies, of whom there were really five, and the Kings Men), guitarist and singer Rudy Greene, singers Bobbie James and Honey Brown, jazz pianist and singer Robert "Prince" Cooper, and veteran piano bluesman Sunnyland Slim. Quality accompaniment was initially provided by Eddie Chamblee's groups. After Chamblee left town for a while, his place was taken by guitarist Lefty Bates, whose studio band featured strong tenor sax work by Red Holloway and Lucius Washington. The doo-wop material was reissued years ago on LP, and the Sunnyland Slim sides were picked up a few years ago by Classics, but strong performances by Honey Brown, Rudy Greene, and Prince Cooper have been overlooked by reissue programs. Davis also showed some interest in gospel groups, but the closest he came to releasing anything was passing a few acetates of the Highway Travelers out to DJs; he also gave limited circulation to an acetate by the "Spitual" Voices, and recorded one other gospel group that we know of. Direct-to-78 demos survive that Davis cut in the back of his store for aspiring vocal groups, as well as acetates by various singers and jazz combos; an acetate by a blues singer has been issued on LP.[Revised 2/28/2020]

The Club 51 label was a side business for local roller skating impresario and record store owner Jimmie Davis. Davis operated the label from March 1955 to some point in 1957. In all there were just 7 releases on Club 51 (three other records that we know of were given limited circulation on test pressings but not actually released). The label's artist roster consisted of two doo-wop groups (the "Four" Buddies, of whom there were really five, and the Kings Men), guitarist and singer Rudy Greene, singers Bobbie James and Honey Brown, jazz pianist and singer Robert "Prince" Cooper, and veteran piano bluesman Sunnyland Slim. Quality accompaniment was initially provided by Eddie Chamblee's groups. After Chamblee left town for a while, his place was taken by guitarist Lefty Bates, whose studio band featured strong tenor sax work by Red Holloway and Lucius Washington. The doo-wop material was reissued years ago on LP, and the Sunnyland Slim sides were picked up a few years ago by Classics, but strong performances by Honey Brown, Rudy Greene, and Prince Cooper have been overlooked by reissue programs. Davis also showed some interest in gospel groups, but the closest he came to releasing anything was passing a few acetates of the Highway Travelers out to DJs; he also gave limited circulation to an acetate by the "Spitual" Voices, and recorded one other gospel group that we know of. Direct-to-78 demos survive that Davis cut in the back of his store for aspiring vocal groups, as well as acetates by various singers and jazz combos; an acetate by a blues singer has been issued on LP.[Revised 2/28/2020]

Cobra, the immediate successor to Abco, has gained tremendous posthumous fame on account of its blues recordings. On July 11, 1956, what was then still Abco recorded bluesmen Otis Rush and Walter Horton and two doowop groups, The Clouds and The Calvaes, in one long session at Boulevard Studio. Within a month, however, Joe Brown had dropped out. Eli Toscano found a new business partner in Howard Bedno (1919-2006), replaced Joe Brown's Lawn Music with his own Armel Music, and opened Cobra, which began its releases at the beginning of September. Cobra 5000, "I Can't Quit You Baby," a national R&B hit for Otis Rush, enabled the company to build its roster. Cobra continued recording through the end of 1958, even spinning off a small subsidiary called Artistic. There were 34 releases on Cobra and 6 on Artistic. Artists included the West Side blues triumvirate of Otis Rush, Magic Sam, and Buddy Guy, all of whom did their first commercial recordings for the company; singers Harold Burrage, Betty Everett, and Gloria Irving; the R and B combos of Duke Jenkins and Ike Turner; and additional blues contributions by Sunnyland Slim, Lee Jackson, Little Willie Foster, Clarence Jolly, Guitar Shorty, and Shakey Jake. The recession hit Cobra hard in 1958; Toscano had ambitions to record gospel and rock and roll, but all that came of them were one release each by the Reverend Robert Ballinger and by the Rock-A-Beats. Willie Dixon was in charge of the company's sessions, with some assistance from Ike Turner during the second half of 1958; starting in March 1957, most recording was done by Eli Toscano in his homemade studio at 3346 West Roosevelt Road. Howard Bedno left at the end of 1958 and ended up working for Chess. The last Cobra release appeared in August 1959, and the company was defunct before the year was out. For a couple of years Richard Stamz, proprietor of such labels as Paso and Fox, took over the former Cobra complex. Before his death in a boating accident in 1967, Toscano sold Armel Music to Jimmy Bracken of Vee-Jay. Some time between 1969 and 1975, the remains of Abco, Cobra, and Artistic ended up in the hands of Stan Lewis. Some Cobras were reissued on singles during Toscano's lifetime. LP reissues began with Blue Horizon in 1969 and picked up again around 1980 with Stan Lewis's licensees, Flyright in Britain and P-Vine Special in Japan, then on Lewis's own label, Paula. Because of the ongoing interest in the Otis Rush and Magic Sam material, most of the Cobras and Artistics have been well served by reissue programs.[Revised 10/7/2020]

Cobra, the immediate successor to Abco, has gained tremendous posthumous fame on account of its blues recordings. On July 11, 1956, what was then still Abco recorded bluesmen Otis Rush and Walter Horton and two doowop groups, The Clouds and The Calvaes, in one long session at Boulevard Studio. Within a month, however, Joe Brown had dropped out. Eli Toscano found a new business partner in Howard Bedno (1919-2006), replaced Joe Brown's Lawn Music with his own Armel Music, and opened Cobra, which began its releases at the beginning of September. Cobra 5000, "I Can't Quit You Baby," a national R&B hit for Otis Rush, enabled the company to build its roster. Cobra continued recording through the end of 1958, even spinning off a small subsidiary called Artistic. There were 34 releases on Cobra and 6 on Artistic. Artists included the West Side blues triumvirate of Otis Rush, Magic Sam, and Buddy Guy, all of whom did their first commercial recordings for the company; singers Harold Burrage, Betty Everett, and Gloria Irving; the R and B combos of Duke Jenkins and Ike Turner; and additional blues contributions by Sunnyland Slim, Lee Jackson, Little Willie Foster, Clarence Jolly, Guitar Shorty, and Shakey Jake. The recession hit Cobra hard in 1958; Toscano had ambitions to record gospel and rock and roll, but all that came of them were one release each by the Reverend Robert Ballinger and by the Rock-A-Beats. Willie Dixon was in charge of the company's sessions, with some assistance from Ike Turner during the second half of 1958; starting in March 1957, most recording was done by Eli Toscano in his homemade studio at 3346 West Roosevelt Road. Howard Bedno left at the end of 1958 and ended up working for Chess. The last Cobra release appeared in August 1959, and the company was defunct before the year was out. For a couple of years Richard Stamz, proprietor of such labels as Paso and Fox, took over the former Cobra complex. Before his death in a boating accident in 1967, Toscano sold Armel Music to Jimmy Bracken of Vee-Jay. Some time between 1969 and 1975, the remains of Abco, Cobra, and Artistic ended up in the hands of Stan Lewis. Some Cobras were reissued on singles during Toscano's lifetime. LP reissues began with Blue Horizon in 1969 and picked up again around 1980 with Stan Lewis's licensees, Flyright in Britain and P-Vine Special in Japan, then on Lewis's own label, Paula. Because of the ongoing interest in the Otis Rush and Magic Sam material, most of the Cobras and Artistics have been well served by reissue programs.[Revised 10/7/2020]

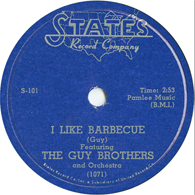

For many years, Jimmy Coe (1921-2004) was the top saxophonist in Indianapolis. We have included him because Naptown was not a recording center, and his important work for States was cut in Chicago, as well as his session activity for Note. Coe first hit the big time in 1942 as the baritone saxophonist in the Jay McShann band with Charlie Parker (he also played alto during a couple of spells when Bird was out of the band). He served in the military from 1943 to 1945, then returned to Indianapolis. After touring with Tiny Bradshaw's band in 1947, Coe studied music at Butler University. From 1950 through 1952 he led the house band at the Cotton Club in Cincinnati, which led to a session of his own for King (featuring his alto sax) and a guest appearance on a Tiny Bradshaw session (both were done in 1952). When King showed no interest in his composition "After Hours Joint," Coe moved over to Leonard Allen's States label, where he cut two sessions in 1953 featuring his tenor sax. United and States had many fine saxophonists in their employ—Tab Smith, Paul Bascomb, Eddie Chamblee, Chris Woods, Jimmy Forrest, Gene Ammons, Cozy Eggleston—but Coe's may be the very best of their small combo recordings. In 1958 and 1959, Coe did session work (some of it on baritone sax) for Indianapolis-based Note Records, backing two doowop groups (the Five Stars and The Students) and rock and rollers Ronnie Haig and Jerry Siefert; he managed to slip in two instrumental sides. These Note sides were recorded at Chess Studios in Chicago. In 1966 Coe operated a short-lived label of his own called Intro, which was responsible for three known releases on 45s. He made another small-label 45 in 1976. In the mid-1980s Coe intensified his musical activity after retiring from his day job. Because of the slow pace of the music business in Naptown, he did not record as much we might expect from his continuing activity as a musician; however, he was able to issue a CD featuring his big band in 1994. He made a second CD in 2000 with guitarist Paul Weeden, and appeared that same year on a jazz repertory CD put together by Naptown drummer Jack Gilfoy. In 2002 Jimmy Coe was recorded in Switzerland (it was his very first European tour!) with Red Holloway, Carrie Smith, and others. His arrangements also appeared on at least one CD around the turn of the century. After battling colon cancer and diabetes (he was still playing in public as late as November 2003), Jimmy Coe died in Indianapolis on February 26, 2004.[Latest update 1/14/2020]

For many years, Jimmy Coe (1921-2004) was the top saxophonist in Indianapolis. We have included him because Naptown was not a recording center, and his important work for States was cut in Chicago, as well as his session activity for Note. Coe first hit the big time in 1942 as the baritone saxophonist in the Jay McShann band with Charlie Parker (he also played alto during a couple of spells when Bird was out of the band). He served in the military from 1943 to 1945, then returned to Indianapolis. After touring with Tiny Bradshaw's band in 1947, Coe studied music at Butler University. From 1950 through 1952 he led the house band at the Cotton Club in Cincinnati, which led to a session of his own for King (featuring his alto sax) and a guest appearance on a Tiny Bradshaw session (both were done in 1952). When King showed no interest in his composition "After Hours Joint," Coe moved over to Leonard Allen's States label, where he cut two sessions in 1953 featuring his tenor sax. United and States had many fine saxophonists in their employ—Tab Smith, Paul Bascomb, Eddie Chamblee, Chris Woods, Jimmy Forrest, Gene Ammons, Cozy Eggleston—but Coe's may be the very best of their small combo recordings. In 1958 and 1959, Coe did session work (some of it on baritone sax) for Indianapolis-based Note Records, backing two doowop groups (the Five Stars and The Students) and rock and rollers Ronnie Haig and Jerry Siefert; he managed to slip in two instrumental sides. These Note sides were recorded at Chess Studios in Chicago. In 1966 Coe operated a short-lived label of his own called Intro, which was responsible for three known releases on 45s. He made another small-label 45 in 1976. In the mid-1980s Coe intensified his musical activity after retiring from his day job. Because of the slow pace of the music business in Naptown, he did not record as much we might expect from his continuing activity as a musician; however, he was able to issue a CD featuring his big band in 1994. He made a second CD in 2000 with guitarist Paul Weeden, and appeared that same year on a jazz repertory CD put together by Naptown drummer Jack Gilfoy. In 2002 Jimmy Coe was recorded in Switzerland (it was his very first European tour!) with Red Holloway, Carrie Smith, and others. His arrangements also appeared on at least one CD around the turn of the century. After battling colon cancer and diabetes (he was still playing in public as late as November 2003), Jimmy Coe died in Indianapolis on February 26, 2004.[Latest update 1/14/2020]

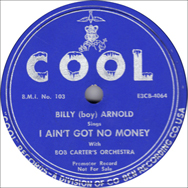

Cool, one of the tiniest of Chicago indepedents, opened in March 1953 and probably closed in October. Cool was a division of Co-Ben recording, a partnership between Collenane Cosey (1909-2010) and her brother-in-law, Charlie Bennett, aka Logan Bennett or Peachtree Logan. One source credits Gwendolyn Bennett, Collenane's sister and Charlie's wife, as a third partner. Collenane Cosey was a songwriter, the widow of alto saxophonist Antonio Cosey (1906-1951), and the mother of guitarist Pete Cosey (1943-2012). Co-Ben/Cool's address was 1231 South Holman Avenue, and the company used RCA Victor for mastering and pressing, as well as recording. Co-Ben made one known session, in March 1953, leading to two releases on Cool in July 1953. Cool 101/102 featured blues shouter Herbert Beard, about whom we otherwise know nothing. One of the Beard sides, a Collenane Cosey composition, was covered by Louis Jordan, whose January 1954 recording, issued around a year later by Aladdin, must have brought Cosey more money in composer royalties than she made off her company's recordings. Cool 103 was the debut release by harmonica-playing bluesman Billy Boy Arnold, who was 17 when it was made. Arnold published his autobiography (The Blues Dream of Billy Boy Arnold, with Kim Field) in 2021. His memories of recording for Cool are largely supportive of what we had already concluded about the session, which took place at RCA Victor (we did not know which musicians Arnold had planned to work with). Arnold and Beard ended up both being backed by a studio band led by bassist Bob Carter. This was the Robert James Carter who played bass and recorded for Specialty, Sunbeam, and Universal in 1946 and 1947, and led a studio ork on a 1949 session for a one-shot label called Rim. Dan Kochakian found the second and last trade paper advertisement for Cool (in Cash Box, September 19, 1953), which promised another Herbert Beard single and a single by co-owner Charlie Bennett. Though these had been promised in the early announcements for the company and we have every reason to think they were recorded, they never materialized. Cool had one distributor (Hy Frumkin, in Chicago). Its 78s and 45s barely sold (we would still like to see a 45 by Herbert Beard; we presume that RCA Victor pressed some) and are preposterously rare today. As of 2018, all 4 released sides have finally appeared on some kind of reissue, a mere 65 years since the company folded.[Revised 4/7/2024]

Tommy Dean was born in Franklin, Louisiana on September 6, 1909. While he was a child, his family moved to Beaumont, Texas, though in the late 1920s Tommy Dean spent some time in Lake Charles, Louisiana. The 1930 census listed his occupation as "musician"; during that period, he was working regularly with Texas-based carnivals and circuses. Probably in 1937, he moved to St. Louis after being hired away from a traveling show by bandleader Eddie Randle. Soon he was running his own combo, which toured regularly from his new base in St. Louis. he pianist and bandleader began occasonal appearances in Chicago in 1945, and would rely on Chicago-based labels for all but one of his recordings. He led a tight, swinging R&B combo with considerable jazz content, making records for Town and Country, Miracle, States, Chance, and Vee-Jay between 1947 and 1958. (His last two sessions for Vee-Jay were left unreleased.) During the 1950s, Dean successfully added organ, sometimes playing piano with one hand and organ with the other. Among the members of Tommy Dean's bands were outstanding alto saxophonist Chris Woods (1925-1985), alto saxophonist and arranger Oliver Nelson (1932-1975), baritonist Gene Easton (1927-1998), guitarist Grant Green (1935-1979; Green's recording debut was a 1956 session that remains entirely unissued), drummer Pee Wee Jernigan, and singers Jewel Belle and Joe Buckner (1924-1996). Dean also recorded with singers Melvin "Pee Wee" Matthews and Freddie "Barrel House" Blott. Continuing to tour after his Vee-Jay contract expired, he led a combo through 1960. From 1962 through 1964, he worked as a single, playing the organ in Saint Louis restaurants. Tommy Dean died suddenly in January 1965, probably of a heart attack.[Latest update 8/1/19]

Tommy Dean was born in Franklin, Louisiana on September 6, 1909. While he was a child, his family moved to Beaumont, Texas, though in the late 1920s Tommy Dean spent some time in Lake Charles, Louisiana. The 1930 census listed his occupation as "musician"; during that period, he was working regularly with Texas-based carnivals and circuses. Probably in 1937, he moved to St. Louis after being hired away from a traveling show by bandleader Eddie Randle. Soon he was running his own combo, which toured regularly from his new base in St. Louis. he pianist and bandleader began occasonal appearances in Chicago in 1945, and would rely on Chicago-based labels for all but one of his recordings. He led a tight, swinging R&B combo with considerable jazz content, making records for Town and Country, Miracle, States, Chance, and Vee-Jay between 1947 and 1958. (His last two sessions for Vee-Jay were left unreleased.) During the 1950s, Dean successfully added organ, sometimes playing piano with one hand and organ with the other. Among the members of Tommy Dean's bands were outstanding alto saxophonist Chris Woods (1925-1985), alto saxophonist and arranger Oliver Nelson (1932-1975), baritonist Gene Easton (1927-1998), guitarist Grant Green (1935-1979; Green's recording debut was a 1956 session that remains entirely unissued), drummer Pee Wee Jernigan, and singers Jewel Belle and Joe Buckner (1924-1996). Dean also recorded with singers Melvin "Pee Wee" Matthews and Freddie "Barrel House" Blott. Continuing to tour after his Vee-Jay contract expired, he led a combo through 1960. From 1962 through 1964, he worked as a single, playing the organ in Saint Louis restaurants. Tommy Dean died suddenly in January 1965, probably of a heart attack.[Latest update 8/1/19]

The Dozier Boys were a vocal/instrumental group that remained active for 24 years. The core members were Eugene Teague (1928-1958), who played guitar, Cornell Wiley (1929- ), who played string bass and handled the arrangements, and Benny Cotton (c. 1929- ), who started out strictly as a singer and eventually became the drummer as well. Other members at different times included Bill Minor, Frank Bell, Joe Boyce, Bobby Blevins, Pee Wee Branford, Truxton Kingslow, Wes Montgomery, Clifford Scott, and Jerry Hubbard. When they needed a session pianist, the Doziers used Sonny Blount (aka Sun Ra) for a 1948 session and King Fleming in 1950. The Doziers came out of a Swing-era tradition of vocal harmonizing that can be heard on most of their sides. In the late 50s, they made an effort to adapt to rock and roll, and they continued to tour and perform until 1970. Their recordings for Aristocrat, Chess, United (featuring sterling accompaniment by guest saxophonist Tab Smith), and other labels deserve more attention from jazz and doowop aficionados than they have gotten so far. [Latest update 11/15/16]

The Dozier Boys were a vocal/instrumental group that remained active for 24 years. The core members were Eugene Teague (1928-1958), who played guitar, Cornell Wiley (1929- ), who played string bass and handled the arrangements, and Benny Cotton (c. 1929- ), who started out strictly as a singer and eventually became the drummer as well. Other members at different times included Bill Minor, Frank Bell, Joe Boyce, Bobby Blevins, Pee Wee Branford, Truxton Kingslow, Wes Montgomery, Clifford Scott, and Jerry Hubbard. When they needed a session pianist, the Doziers used Sonny Blount (aka Sun Ra) for a 1948 session and King Fleming in 1950. The Doziers came out of a Swing-era tradition of vocal harmonizing that can be heard on most of their sides. In the late 50s, they made an effort to adapt to rock and roll, and they continued to tour and perform until 1970. Their recordings for Aristocrat, Chess, United (featuring sterling accompaniment by guest saxophonist Tab Smith), and other labels deserve more attention from jazz and doowop aficionados than they have gotten so far. [Latest update 11/15/16]

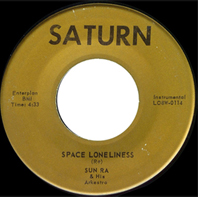

Drexel Records was an extremely modest independent label that operated from 1954 to 1958. Les Caldwell, who had been a salesman for King Records, and Paul King were partners in the label, along with a third individual who has never been publicly identified. The company never had its own business office; it was run out of Paul King's home at 7319 South Vernon. Drexel was responsible for 18 releases, all singles. The company's focus was R&B vocalists and vocal groups. The most recorded artists were The Gems, a vocal quintet whose lead singer Ray Pettis also made solo recordings for the label. The other featured artists were a vocal group called the Gay Notes, and singers Dorothy Logan, Dave Turner, Hattie Randolph, Bobby Elvin, and Roy Wright. Drexel did not promote its records effectively; they got some radio play locally, but the only distributor we can find for the label was United in Chicago and very few were ever sold anywhere else. Coverage in the trade papers, though more than one might expect for such a small operation, was fitful. The Gems broke up because they had realized virtually no income from their Drexel releases. Of the label's other artists, only Hattie Randolph is known today, on account of her slightly later recordings for Sun Ra and Alton Abraham's own small label, Saturn. Dave Turner earned local notoriety as a comic and an MC, hitting his peak of visibility when he toured with Dinah Washington, but nothing has been heard of him since 1963. All the same, the company's releases offered high production values, including excellent sound quality (courtesy of Universal Recording), and strong performances overall. Drexel's session musicans have still not been fully researched, but in 1956 pianist and combo leader Denni Tillman was identified as the label's music director, and veteran saxophonists Bert Patrick, Johnny Houser, and Red Holloway were involved at one time or another. Trombonist Johnny Avant also appeared on one session for the label. Reissue interest in Drexel has focused on the Gems, whose singles have been "reproed" by doowop aficionados. One Drexel reissue on CD (extensive, but not complete, at 29 out of the 36 released sides) is a bootleg. Another CD from 2018 includes four sides by Drexel's male vocalists.[Revised 5/12/2024]

Drexel Records was an extremely modest independent label that operated from 1954 to 1958. Les Caldwell, who had been a salesman for King Records, and Paul King were partners in the label, along with a third individual who has never been publicly identified. The company never had its own business office; it was run out of Paul King's home at 7319 South Vernon. Drexel was responsible for 18 releases, all singles. The company's focus was R&B vocalists and vocal groups. The most recorded artists were The Gems, a vocal quintet whose lead singer Ray Pettis also made solo recordings for the label. The other featured artists were a vocal group called the Gay Notes, and singers Dorothy Logan, Dave Turner, Hattie Randolph, Bobby Elvin, and Roy Wright. Drexel did not promote its records effectively; they got some radio play locally, but the only distributor we can find for the label was United in Chicago and very few were ever sold anywhere else. Coverage in the trade papers, though more than one might expect for such a small operation, was fitful. The Gems broke up because they had realized virtually no income from their Drexel releases. Of the label's other artists, only Hattie Randolph is known today, on account of her slightly later recordings for Sun Ra and Alton Abraham's own small label, Saturn. Dave Turner earned local notoriety as a comic and an MC, hitting his peak of visibility when he toured with Dinah Washington, but nothing has been heard of him since 1963. All the same, the company's releases offered high production values, including excellent sound quality (courtesy of Universal Recording), and strong performances overall. Drexel's session musicans have still not been fully researched, but in 1956 pianist and combo leader Denni Tillman was identified as the label's music director, and veteran saxophonists Bert Patrick, Johnny Houser, and Red Holloway were involved at one time or another. Trombonist Johnny Avant also appeared on one session for the label. Reissue interest in Drexel has focused on the Gems, whose singles have been "reproed" by doowop aficionados. One Drexel reissue on CD (extensive, but not complete, at 29 out of the 36 released sides) is a bootleg. Another CD from 2018 includes four sides by Drexel's male vocalists.[Revised 5/12/2024]

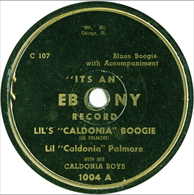

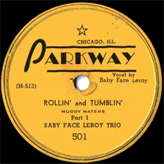

Ebony, Chicago, Southern and Harlem were independent labels operated by music business veteran J. Mayo Williams (1893 or 1894-1980), Williams had already enjoyed success as a professional football player and as an Artists and Repertoire man for Paramount and Decca when he went out on his own in January 1945. There were three phases to his independent label operations. From 1945 to 1949, he operated the Chicago (later Southern), and Harlem labels, dividing his time between New York City and Chicago (he was also involved with Ebony Distributors, out of New York). He started a red Ebony label in 1945, but seems to have shelved it after a year. But in 1947, he picked up with a new, very small Ebony operation in Chicago, with a new label design (on black or on red), an "Ink," Inc. logo, and no formal ties to Harlem-Chicago-Southern. To achieve wider distribution, he often struck deals in his early period with other companies, notably Syd Nathan's King Records, Ivan Ballen's 20th Cenury and Apex labels, and his former employer, Decca. The need become more urgent after he closed his New York office and its distribution wing (probably around the beginning of 1948). After a brief hiatus in 1950 and1951, he reopened an Ebony label based in Chicago; between 1952 and 1959, it was responsible for 31 known releases. For a little while, Williams licensed some of these Ebony masters to Art Sheridan's Chance label and Joe Brown's JOB. After being sidelined by illness in 1959, Williams regrouped and started a final incarnation of Ebony, which was responsible for at least 24 releases through 1971; some of these were licensed to Decca's Trend subsidiary. Williams always had a nose for talent, but eccentric concepts of marketing and no flair for popular music production. Consequently, releases on his labels have drawn little attention over the years. During the Chicago-Southern-Harlem era, Wiliams featured such artists as Bob Camp, Lee Brown, Dossie Terry, J. T. Brown, Johnny Temple, Brother John Sellers, the Famous Blue Jay Singers, the Dixieaires, and Tab Smith. He also gave bluesmen Jimmy Rogers, Muddy Waters, and Leroy Foster their first opportunities to record commercially—though not to get a whole lot of publicity. The first Chicago-based Ebony label recorded Lil "Caldonia" Palmore. During the Ebony II period, Williams recorded blues artists Birmingham Junior, Freddie Hall, Little Brother Montgomery, Earl Dranes, and Alfred "Blues King" Harris, gospel performers such as Brother George Curry, a doowop group (the Eagle-Aires), and R and B acts including Joe "Cool Breeze" Bell and more of Lil Palmore (who was now going as Cal Palmer). He also indulged in some trickery, overdubbing a 1945 Tab Smith instrumental with heavy drumming by Jack Cooley and marketing the resulting hybrid as "Tab's Rocker" and "Cooley's Cowboy Rock." The Ebony III period was less successful artistically (Williams intensified the overdubbing, applying it now to Decca recordings from the 1930s, and his new sessions gave undue attention to organ combos and lounge singers) but it provided opportunies to veterans such as Lil Hardin Armstrong and newcomers such as Bonnie "Bombshell" Lee. By 1973, Williams had a bunch of leftover Ebony 45s that he wanted to unload in quantity. Williams' manner of numbering his releases was wayward (there's no telling how many different Ebony 1000s he put out), his Ebony II and III operations had a makeshift distribution network confined to Chicago, and most of his records are very rare today; we are sure some remain to be discovered. [Revised 10/28/2022]

Ebony, Chicago, Southern and Harlem were independent labels operated by music business veteran J. Mayo Williams (1893 or 1894-1980), Williams had already enjoyed success as a professional football player and as an Artists and Repertoire man for Paramount and Decca when he went out on his own in January 1945. There were three phases to his independent label operations. From 1945 to 1949, he operated the Chicago (later Southern), and Harlem labels, dividing his time between New York City and Chicago (he was also involved with Ebony Distributors, out of New York). He started a red Ebony label in 1945, but seems to have shelved it after a year. But in 1947, he picked up with a new, very small Ebony operation in Chicago, with a new label design (on black or on red), an "Ink," Inc. logo, and no formal ties to Harlem-Chicago-Southern. To achieve wider distribution, he often struck deals in his early period with other companies, notably Syd Nathan's King Records, Ivan Ballen's 20th Cenury and Apex labels, and his former employer, Decca. The need become more urgent after he closed his New York office and its distribution wing (probably around the beginning of 1948). After a brief hiatus in 1950 and1951, he reopened an Ebony label based in Chicago; between 1952 and 1959, it was responsible for 31 known releases. For a little while, Williams licensed some of these Ebony masters to Art Sheridan's Chance label and Joe Brown's JOB. After being sidelined by illness in 1959, Williams regrouped and started a final incarnation of Ebony, which was responsible for at least 24 releases through 1971; some of these were licensed to Decca's Trend subsidiary. Williams always had a nose for talent, but eccentric concepts of marketing and no flair for popular music production. Consequently, releases on his labels have drawn little attention over the years. During the Chicago-Southern-Harlem era, Wiliams featured such artists as Bob Camp, Lee Brown, Dossie Terry, J. T. Brown, Johnny Temple, Brother John Sellers, the Famous Blue Jay Singers, the Dixieaires, and Tab Smith. He also gave bluesmen Jimmy Rogers, Muddy Waters, and Leroy Foster their first opportunities to record commercially—though not to get a whole lot of publicity. The first Chicago-based Ebony label recorded Lil "Caldonia" Palmore. During the Ebony II period, Williams recorded blues artists Birmingham Junior, Freddie Hall, Little Brother Montgomery, Earl Dranes, and Alfred "Blues King" Harris, gospel performers such as Brother George Curry, a doowop group (the Eagle-Aires), and R and B acts including Joe "Cool Breeze" Bell and more of Lil Palmore (who was now going as Cal Palmer). He also indulged in some trickery, overdubbing a 1945 Tab Smith instrumental with heavy drumming by Jack Cooley and marketing the resulting hybrid as "Tab's Rocker" and "Cooley's Cowboy Rock." The Ebony III period was less successful artistically (Williams intensified the overdubbing, applying it now to Decca recordings from the 1930s, and his new sessions gave undue attention to organ combos and lounge singers) but it provided opportunies to veterans such as Lil Hardin Armstrong and newcomers such as Bonnie "Bombshell" Lee. By 1973, Williams had a bunch of leftover Ebony 45s that he wanted to unload in quantity. Williams' manner of numbering his releases was wayward (there's no telling how many different Ebony 1000s he put out), his Ebony II and III operations had a makeshift distribution network confined to Chicago, and most of his records are very rare today; we are sure some remain to be discovered. [Revised 10/28/2022]

Pianist, singer, and arranger King Fleming (1922-2014) worked steadily as a jazz musician for 65 years. In 1939, he was leading an 8-piece band that played for high school dancers in Chicago. From September 1942 through July 1943, his Swing band (initially, 11 pieces) was a big local draw. After military service, he worked on the West Coast in 1945 and 1946; he was a member of the Johnny Alston and King Perry bands, recording behind Wynonie Harris on one occasion. He returned to Chicago late in 1946 and appeared regularly in the clubs with a trio or quartet. From 1953 through 1959, this was a highly distinctive vocal/instrumental ensemble, with a female lead vocalist (Ethel Duncan, Lorez Alexandria, or Lurlean Harris), Fleming singing and playing piano, plus a singing bassist (Russell Williams) and a singing drummer (Aubrie Jones). Fleming's first recording as a leader, done in 1954 with an augmented quartet, featured singer Lorez Alexandria (1925-2001) and legendary Chicago tenorist John Neely (1930-1994). From 1955 through 1957, he appeared on three sessions for Chess, leading vocal-instrumental groups, but just one 45 rpm single under his own name resulted; fortunately a demo disk has surfaced of the two tunes his group recorded at its first Chess session. In 1957, he backed Lorez Alexandria on her first two albums for the King label, the first done with an expanded King Fleming trio, the second with an all-star jazz group. During this period he also collaborated with Muhal Richard Abrams, who wrote arrangements for a big band that King Fleming led. The last vocal-instrumental group, featuring Lurlean Harris as the female vocal lead, broke up in 1959. From 1960 through 1965, Fleming returned to the Chess brothers, recording three outstanding piano trio albums for their jazz labels Argo and Cadet; these are all available, as of 2014, on a 2-CD Fresh Sounds reissue. Otherwise his recording opprortunities up through 1970 were limited to three boutique-label singles, on which he backed George "Stardust" Green, and arranger chores that he shared with Will Jackson for an Argo LP by Johnny Nash and another by the Ramsey Lewis Trio with strings. After 25 years of regular work in the Chicago area went by without any more opportunities to record his own music, while he turned down some offers he got to record pop tunes, King Fleming approached Bradley Parker-Sparrow and Joanie Pallatto's Southport label in 1995 about doing a CD of his compositions. King! came out in 1996. In 2000, Fleming suggested a collaboration with singer Joanie Pallatto, for which she wrote lyrics to five of his instrumental pieces; The King and I was released that same year. The King Fleming Trio continued to work in the Chicago area through 2003; King Fleming retired from performing in 2005. King Fleming died at the Illinois Home for Veterans in Manteno, Illinois, on April 1, 2014, at the age of 91.[Revised 3/9/2020]

Glo Tone may be the most obscure and fleeting of all the Chicago independents. We learned who owned it (trumpeter Melvin Moore) because long after the label went inactive, Billboard listed it with his parents' address ("Chicago 37, Illinois," is all that the labels say). Melvin Eugene Moore, who was born in Chicago on June 15, 1923, led the cornet and trumpet section of the Du Sable High School marching band, and had already recorded with Marl Young on 5 sessions. We don't know whether Glo Tone did its one recording session in the second half of 1948 or the first month of 1949 (United Broadcasting deliberately kept a mixed up matrix number series during that period). What we do know is that Glo Tone released two singles by Moore's fairly big bop band. One side featured a vocal group called the Original Calypso Boys and the other three gave the spotlight to a still-scuffling nightclub singer named Joe Williams. And the arrangements as well as the presence of a Marl Young composition already recorded for Sunbeam ("Too Lazy to Work, Too Nervous to Steal") hint at some piece of business left unfinished by the closedown of that label—in November 1947, when Young moved to Los Angeles. Glo Tone vanished after less than a year in operation. Joe Williams went on to record for Columbia, OKeh, and Blue Lake and finally caught his break in 1954. Melvin Moore made a brief stop at Chance and a slightly longer one at Vee-Jay before making his own move to Southern California, where he would eventually work with Charles Mingus and Johnny Otis, and play in the band for "Here's Lucy" under the direction of Marl Young. Melvin Moore died in Inglewood, California on February 27, 1989.[Revised 9/3/2018]

Gold Seal opened for business the first week of September 1946. The label was owned and managed by Leonard Klein, previously an employee of United Broadcasting Studios. It sought niches in jazz, Country and Western, and popular vocals and keyboard music. Gold Seal was the only company to make commercial recordings of the highly eclectic, classically trained pianist Robert Crum (1915-1981); it issued a 3-pocket album of his duets with uncharacteristically reticent drumming by Barrett Deems (1914-1998). Gold Seal also quickly absorbed Jack Green's abortive effort (October 1946) to promote jazz concerts in Chicago and record the artists. Three Gold Seal releases materialized, by a Max Miller piano trio, a quartet led by pianist Paul Jordan (1916-1989) featuring Bud Freeman on tenor saxophone, and a bold late-Swing experiment in arranging for an octet, also led by Jordan; the fate of the many other sides recorded for Green remains unknown. In the Country arena, Gold Seal availed itself of the services of musicians and DJs who worked for Chicago-area radio stations: an October 1946 session and one each from October and November 1947 were credited to the Ranch House Boys. The company announced the signing of operatically trained singer Arthur Lee Simpkins (1907-1972), who, because opera productions and aria and lieder recitals were effectively closed to black performers, worked in hotel lounges and fancy nightclubs; Billboard said that Gold Seal released a single on him, but confirmation would be nice. Gold Seal's most prolific artist was Kenny Jagger (1918-2010), who played piano with one hand and organ with the other and was a big draw on the "cocktail single" circuit. Jagger, who recorded in September and November 1946, was responsible for at least 10 releases; toward the end of the company's run, four of his singles were bundled into an album. Along with standards, light classics, and polkas, he cut a solid rendition of Pinetop's "Boogie Woogie." Inactive in the recording studio during the first 9 months of 1947, Gold Seal tried to regroup by purchasing masters from Bel-Tone, a Los Angeles-based company that had been in operation from July 1945 through November 1946. Gold Seal wanted and got more Country, releasing two singles by Merle Travis, two by Eddie Dean, and one each by Dale Evans, Monte Hale, and Herman the Hermit; four of these were packaged into an album, Cowboy Songs with Cliffie Stone and his orchestra, and there could still be more Bel-Tone reissues that we have not located. Gold Seal also reissued three Country records by Red Murrell, which originally appeared on a Southern California label called Acme. It snagged the first two sides by singer Frankie Laine (a hot commodity after Mercury signed him in 1946) and two by the great singer and trumpet player Valaida Snow (1904-1956). Gold Seal's own recordings, made at Bachman Studio and (of course) United Broadcasting, had very good sound quality, but pressings were grainy, the company never had much distribution, and it was so strapped that that it never bought a single advertisement in Billboard or Cash Box. It was still (feebly) in existence in October 1948, closing before the end of the year without owing enough money to get a final writeup in the trade press. We presently know of 32 Gold Seals. But Gold Seal singles are so obscure, and the company's numbering system so idiosyncratic, that additional undocumented releases probably exist. Nothing has ever been reissued from Gold Seal, except the Max Miller single, which was picked up by his new record company, Life, and the Paul Jordan/Bud Freeman, which made it onto a Classics CD 51 years after it was recorded. [Revised 4/20/2024]