Revision note: A close long at Michel Ruppli's discography of The King Labels has turned up a previously unknown issue of two Miracle masters on Henry Stone's Rockin' label. Rockin' 521, released in 1953, was credited to "Royal Brent," a pseudonym that Thompson occasionally used at King when he was the vocalist on a side. Not having heard this rarity, we don't know which take of "Dreams" or of "Danny Boy" was used, but we do have evidence of a release on each. Prompted by an email from Marv Goldberg (March 28, 2024), we have corrected the dates for Johnny Desmond's TV show (on which the Four Vagabonds appeared). Marv Golberg's research on Gladys Palmer, besides dispelling multiple tall tales that Palmer told about herself, has led us to correct our attributions on takes of "Fool That I Am." It turns out that Miracle released an edited version of the long take 1, whereas take 2 was used on a Federal release after Syd Nathan acquired nearly all of the Miracle masters. Goldberg's research on Bill Samuels has convinced us that the vocal harmonies on several sides from his first session for Miracle could not be the work of the Vagabonds. A brief article by Mike Rowe ("The Miracle/Esquire Mysteries," Bits 'n' Pieces 16/1) corrects a couple of errors we had made about reissues on the British Esquire label, then documents at least two releases that appeared only on Esquire (with artists wrongly identified). We will be adding new information on Browley Guy, also courtesy of Marv Goldberg, who has done extensive research on him (see http://www.uncamarvy.com/BrowleyGuy/browleyguy.html). We can finally report something about Miracle 138, from John Sellers' second session for the label. We've made a few minor corrections to our Sunrise listing. Marv Goldberg also pointed out to us that the guitarist in the Sharps and Flats was Arvid Garrett, not "Arvin." We have concluded that the 6 sides by accordion player Joe Petrak, which appeared on Old Swing-Master in 1949, were not originally recorded for Miracle. We have corrected the recording date for the first two Tommy Dean sides, released on Miracle 135, which were probably cut in Saint Louis. Our thanks to Galen Gart for reminding us that the vocal on "Jump for Joy" is credited on 135 to Pee Wee Matthews, a blues singer then active in Saint Louis. Dean's signing to Miracle was announced on April 30, 1949. We have finally been able to provide a real biography of Lee Egalnick, and to supply further details about Miracle's first year in business. We have added to our coverage of Rudy Richardson, who went to Manor after his two sessions for Miracle, then recorded more extensively for Manor than we'd realized. With help from Mary Unger of Ripon College, we have identified the mysterious S & S Studios. They were located in the back of Lew Simpkins' bookstore.

Chicago-based Miracle Records, in operation from June 1946 to May 1950, was a typical post-World War II independent operation. The company focused its recordings on a particular niche market, the African-American community, and released a variety of rhythm and blues recordings that sounded fresh and new next to the tired "Bluebird Beat" that the majors were putting out. Unlike Aristocrat—a similar Chicago independent that arose a few months later—Miracle did not record the deep Mississippi Delta style blues that was growing in appeal in the city. Instead the company put out balladeers, rhythm instrumentalists, and uptown blues singers. Miracle's recordings represented an era when jazz, rhythm and blues, and pop were not so carefully divided into different musical camps. Jazz musicians were viewed as entertainers as well as artists—as part of the same African American recording world that was producing ballads, blues, jive, and rhythm numbers.

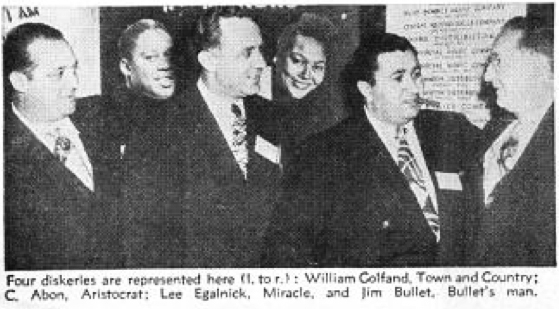

Miracle Records was officially launched in August of 1946. (Recording started in June of that year—see below.) Lee Egalnick served as president of the firm. Lew Simpkins was Egalnick's partner from the beginning.

The Social Security Death Index includes a Lee J. Egalnick who was born June 1, 1921, and was issued his Social Security card in Illinois. Leo L. Egalnick, as he was called in his younger days, was born in Chicago. He was the son of Sam Egalnick (born December 17, 1895) and Celia Turner Egalnick (born July 12, 1899), who lived at 7500 South Phillips Avenue, later at 7719 South Phillips. Leo had an older brother, Charles (born April 12, 1918), and a younger sister, Margaret (who was born October 3, 1929).

He enlisted in the Army Air Force in August 1941, and was sent to Trinidad where he worked as a radio mechanic for an air depot group. Promoted to sergeant, Leo Egalnick transferred to the Brazilian state of Natal, where he was involved in setting up air supply bases for the North African theater. After officer candidate school, he was assigned in April 1943 to the air traffic division in Kansas City and promoted to first lieutenant. On October 3, 1943, the Chicago Tribune (part 7, p. 3) annonced Lt. Lee Egalnick's engagement to Francine Fisher (born November 8, 1922 in Chicago), the daughter of Marvin and Sadye Fisher. But on December 22, Egalnick was court-martialed for padding his travel expenses. At trial he admitted to submitting fraudulent travel vouchers, and on leaving the courtroom he told a reporter, "It was a fair verdict. I had just been trying to live above my incomce." He was sentenced to dismissal from the Army and ordered to pay a $500 fine ("An Army Career Ends in Dismissal," Chillicothe [Missouri] Constitution-Tribune, December 22, 1943, p 7). However, the verdict was subject to review by his commanding officer, at the air service command in Oklahoma City. Apparently the verdict was changed on review, because Lt. Lee L. Egalnick was stationed in Oklahoma City when he and Francine were married, on Valentine's Day (Chicago Tribune, March 19, 1944, part 7, p. 8). In the announcements of his engagement and marriage, he was already being referred to as Lee, as was his preference from then on. His middle initial, in every published reference other than his Social Security information, was given as L. It may have stood for Lawrence.

Miracle's original address was 107 East 47th Street, on the main business strip of the South Side African American community; S&S Recording Studios, with the same address, is mentioned on the labels of the company's earliest releases. Courtesy of Mary Unger, a professor at Ripon College who is researching Black-owned bookstores on the South Side from the 1930s through the 1950s, we have learned that S. & S. was a bookstore—and that Lew Simpkins owned it. Lewis Conrad Simpkins was born in Mississippi on November 7, 1918; he was the son of Lube Simpkins and Lily Jackson Simpkins (see the late Eric LeBlanc's tribute at https://groups.google.com/forum/#!topic/bit.listserv.blues-l/ShkSbJqIdJ0). The family moved to Chicago at an unknown date.

We first catch sight of Lew Simpkins in the business world as the owner S & S Bookstore at 107 East 47th. The store was open by the summer of 1944; in the July-August issue of Negro Story: A Magazine for All Americans, a Chicago-based literary magazine featuring African-American writers (one of the contributors to that issue was Ralph Ellison), S&S Bookstore is listed as one of the magazine's "Agents" or distributors. The magazine closed in 1946, but a 1947 display ad for the store in Scott's Business & Service Directory (p. 124) includes a photo of Lewis Simpkins, Proprietor, "Featuring a Complete Line of Books By and About Negroes plus All Current Best Sellers." In addition, S & S sold the "Latest Records" and boasted of a "New and Modern Recording Studio." Since the ad promoted the use of the studio for "Auditions," we've inferred that it was a small room in the back of the store, rather like Jimmy Davis's studio in the 1950s, and that it was used primarily to make demos. We don't know of commercial releases on Miracle, or on any other label, that were recorded at S & S.

The relationship between Egalnick and Simpkins was something like the relationship between Nathan Rothner and Freddie Williams at Hy-Tone. Operating a store that sold books and records in Bronzeville and inviting performers on the South Side to make demos there, Simpkins had developed the connections that would make him a successful recruiter of talent. Egalnick presumably brought some capital into the company, though we don't know how much—or what business he'd been in for the last year or two. Billboard for November 30, 1946, said he was a "former race record distribber" (p. 36). Who he'd been working for, and in what capacity, we don't know. We also don't know how long, though Egalnick probably remained in the Army Air Force until the war ended. Someone at the new company had a connection with J. Mayo Williams, whose New York distribution operation was handling Miracle early on. Unlike Freddie Williams at Hy-Tone, Simpkins kept his A∓R role for the life of the company, and continued in the record business afterwards.

After just two releases in August, the company went on hiatus for three months.

Then a teaser ad was placed in the November 30 issue of Billboard (p. 46), promising "A Miracle." There was also a one-paragraph article ("Chi Diskery, Agent Teamed," p. 36) on the "opening" of the company; bets were hedged with the announcement that Egalnick and Simpkins were also functioning as booking agents for their artists. On December 7 Billboard ran an ad announcing the launch of the label, "Here It Is! Announcing Miracle The Greatest Label in the Race Field Watch for Sensational New Releases" (by now the trial balloon in August must have been nothing more than a bad memory). Smaller copy on the ad promised "the finest talent" that will make their debut "in the near future."

Over the next few months, the label obviously had done more recording, including a crucial session involving Floyd Hunt and Gladys Palmer, and releases were starting to come out, but there was hardly any attention paid in the trades.

In February 1947, the company's address was still the S. & S. bookstore. It had acquired a New York distributor, Mayo Williams' Ebony operation at 307 Lenox Avenue.

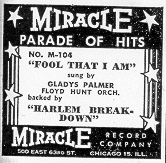

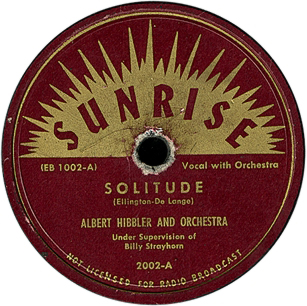

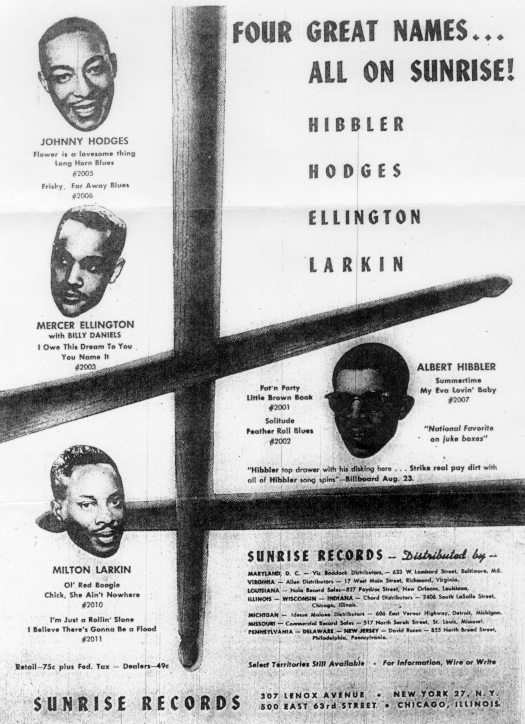

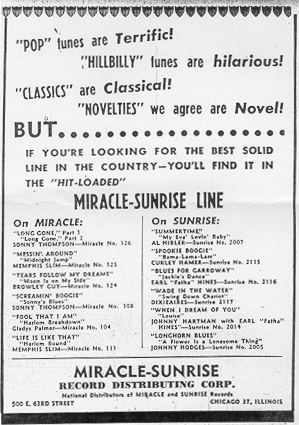

In the Billboard directory of record companies for May 31, 1947, there is a listing for Miracle, at a new address, 500 East 63rd Street, in the heart of a growing nightclub district. Maybe Lew Simpkins had decided to close his bookstore so he could focus on Miracle full-time. Trade ads on the company's acts first appeared in Billboard on August 23, 1947 (indicating enhanced revenue as well as greater marketing ambitions). The occasion for the ad was rising sales for Miracle 104 by Gladys Palmer and Floyd Hunt. Egalnick and Simpkins had built a network of distributors, which was duly sported in the same ad. The single in question, which had been selling for two or three months, and had already been reviewed, was noted as received in the next issue, for August 30.

Ebony would run its own ad (Cash Box, September 22, 1947, p. 24), boasting that it carried Miracle 104. Before the year was out, however, Egalnick and Simpkins thought they could find a New York area distributor with more reach than Ebony had (it's also possible that Mayo Williams was getting ready to leave the distribution business). By the end of November (Cash Box, November 29, 1947, p. 28), the Miracle account had gone to Major Distributing, a New York firm that carried a wide range of independent labels.

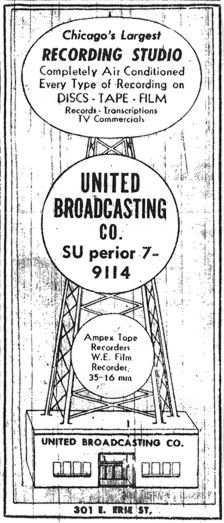

Some early Miracles were made at Myron Bachman's Studio on Carmen Avenue. But the principal recording venue was United Broadcasting Studio, which was owned by Egmont Sonderling. Born in Germany on February 27, 1906, Sonderling immigrated to the US in 1923. After a number of years working as a radio announcer, Sonderling opened United Broadcasting Studio in 1939; the first location was the former RCA Victor studio. In 1945, Sonderling moved his studios to 64 East Lake. Next he opened a pressing plant: a January 5, 1946 ad in Billboard declared Sonderling's readiness to press 2 million platters for delivery during the year. By 1947 Sonderling was calling his operation Master Records, though this seems to have encompassed just the studio and pressing plant; it was not yet being applied to commercial releases. Somewhere between June 1947 and March 1948 (we are using telephone books as our source, so we can't pinpoint the date), Sonderling bought World Broadcasting Studios at 301 East Erie and moved his UB operation there. In January 1949, stuck with a pile of R&B and jazz masters that the defunct Vitacoustic company hadn't paid him for, Sonderling opened a subsidiary called Old Swing-Master in partnership with DJ Al Benson (the label was named after Benson's DJ handle).

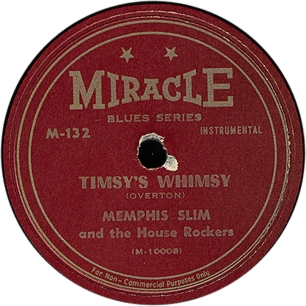

Toward the end of the label's history, 6 sides that Miracle recorded appeared on Old Swing-Master; 2 of the Old Swing-Master releases also came out on Master, which by then was an actual record label. In addition, further sides by Memphis Slim were eventually dealt to Master—we know of 2 singles derived from these—and a single by Jack Cooley (from the early days of Miracle's successor, Premium) was also dealt off to Master. Most likely these sides went to Sonderling in compensation for unpaid studio, mastering, or pressing bills. The Old Swing-Master sides and three of the Master issues bear the original UB matrix numbers and are placed with their original sessions below. Two Memphis Slim issues on Master have no UB numbers; since we do not know the sessions that they came from, we have listed them separately beneath the 1947 recordings for Miracle. (The sides originated with as many as 4 different sessions.)

Recording for Miracle began in June 1946 (see below for details). Meanwhile, Lee and Francine's first son, Robert Allen Egalnick, was born on July 13, 1946.

The first singles that the new company released were the work of effeminate male singer Rudy Richardson, who usually accompanied himself on piano in the clubs. He was often plugged as "America's only male torch singer." One caption said, "his piano boogies are really on the ball too." His first session took place in mid to late June 1946. The release party for two Richardson singles was scheduled for August 16, as advertised in a sizable display in the Chicago Defender.

Richardson was born Rudolph Valentina Riles, in Memphis on September 30, 1923. His father was identified as Cyrus Lockett and his mother as Martha Marie Waidlington, so it could be that his birth father was named Riles. When he was three, his family moved to Chicago, where he atended the Douglas School. After graduating from DuSable High, he entered the club scene; "Rudolphe" Richardson first appears in the Local 208 Board minutes as a leader on April 6, 1944, when he filed an indefinite contract with the Chicken Palace. On September 21, 1944, he posted an indefinite contract with The Hurricane Lounge as "Rudy" Richardson. Richardson was close to continuously employed in Chicago clubs during 1945 and 1946; on February 1, 1945 he filed a contract for 13 weeks at Rudy's Chicken Shack (in which he did not have an ownership interest, so far as we know), and on April 5 he posted one for 8 weeks (3 days per) at The Hurricane. On June 21, 1945, he filed a contract for 12 more weeks at the Chicken Shack (no longer Rudy's). In September of that year he moved over to El Casino (indefinite contract filed on September 20); in December he picked up for 2 weeks at Rupneck's (contract filed December 6).

On the four tunes that formed his first two Miracle releases, Richardson turned over the piano chores to Ted Craig; the trio was completed by William "Lefty" Bates on guitar and Eddie Calhoun on bass. These 78s were apparently released under their matrix numbers, in a 1000 series. But they also carry a second set of matrix numbers in an A-5100 series (and three of these, such as A-5158 seem to have been misprinted, as A-5188). The 1000 series numbers are what appear in the trail-off shellac. The first two Miracles bear the further distinction of being issued on dark blue or purple-blue labels.

The recording date was a Swing-oriented outing, with the excellent work by the trio. "Chauffeur" is a torch song with a pleasant tune, rather amateurish lyrics ("I'm broken-hearted, so discarded"), and a monologue in the middle ("Chauffeur, take me home, I'm really gone... Don't think I'm wiggin', man, I'm just gone, you understand"). Richardson sings his weary plea in a high tenor voice, and Lefty Bates gets a little guitar solo. (We wondered whether the take we heard was issued, as it runs to 3:45 or so. However, the issued "Chauffeur" runs to 3:43—on a 10-inch 78, and it's faded at the end!). "Hick-Botham" is an uptempo Swing number featuring lots of scatting from Richardson and interesting solos by Craig, Calhoun (doing his Slam Stewart thing), and Bates. "I Need You" is a droopy ballad and "I'm Turning in My Chips," despite the torch aspect, could pass for a Nat King Cole number.

Despite the optimistic annotation "Select Rhythm Hits," nothing much seems to have happened commercially with the first two releases, which are rare today. Miracle decided to relaunch itself in December, now with a 100 series and a red label. (Richardson was mentioned in the November 30 article in Billboard.) Still, the company was putting more sides in the can during this period: the diversified investments included a second session by Richardson, as well as items by a jazz vocalist (Gladys Palmer with Floyd Hunt's combo), a blues artist (Memphis Slim), a gospel singer (Brother John Sellers), and a swing combo (the Dick Davis Orchestra).

All of the Rudy Richardson sides appear to have been cut at the same studio, a place whose 1000 series matrix numbers also show up on recordings made around this time for Hy-Tone, Sunbeam, Gold Seal, and Rondo. Richardson's last two sides for the label, released on Miracle 100, bear numbers later in the same 1000 series.

From clues provided by pianist Max Miller, who recorded for Gold Seal in August 1946, and John Steiner, who was familiar with the venue, we have concluded that the 1000-series venue was Myron Bachman's studio on Carmen Avenue, and from evidence about the first releases on Rondo, we've identified mid to late June 1946 as the likely time for Richardson's session. The 1057-1060 block immediately precedes the matrix numbers for a long session by the piano and organ duo of Ruth Noller and Evelyn Straub, and advance orders for one of their Rondo records were being taken by July 5, 1946.

By contrast, the first Dick Davis release, on Miracle 101, carries matrix numbers with the UB prefix, for United Broadcasting, which would become the company's studio of choice in October 1946. Tenor saxophonist Dick Davis (birth name Richard Earl Davis) was born in Jackson, Mississippi on April 15, 1917 (according to the Chicago Federation of Musicians Member Death Files 1940 - 1979). His family moved to Chicago in 1924. He graduated from DuSable High School in January 1938 (the Chicago school ran mid-year and June graduations then). And he won an award while in the DuSable band, which means he was trained by Captain Walter Dyett. On graduating he went promptly to work as a professional musician. The first name band he joined was the Sunset Royals (1938). After World War II service in the Army's 869th Engineer Aviation battalion in the Pacific, where he led the unit's dance band, he returned to Chicago and reestablished himself on the local club scene. He rejoined Local 208 on January 23, 1946 and was soon leading his own group at the Tradesmen's Show Lounge (6240 Cottage Grove Avenue). To make something of his time in the military, his outfit was billed as "Richard E. Davis & His Westcoast Swingsters." Davis spent several months at the Tradesmen's, posting a 1-month contract on June 6 and an 8-week contract on July 18. He also worked the Boulevard Lounge (indefinite contract filed on March 21) and Jimmie's Palm Garden (2-week contract filed May 2).

Dick Davis cut his first recordings for Miracle in June 1946, if we are reading the UB matrix numbers correctly; his first session could even have preceded Rudy Richardson's. He made the customary four sides, but only three were used. They were held for release until the label was relaunched (with Dick Davis as a listed artist) at the end of the year, when they appeared on Miracle 101. (Three sides were used because the company came out with two versions of 101, using different B sides. Somebody had second thoughts about the coupling.)

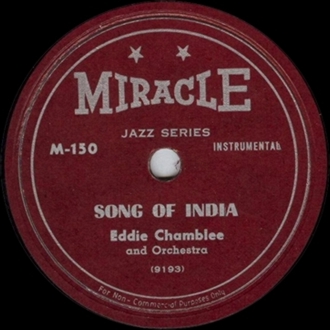

Egalnick and Simpkins got the idea to record Davis with George Rhodes, piano; Eddie Calhoun, bass; and "Little Jimmy" [Hoskins], drums—and an enhanced front line with Tommy "Madman" Jones and Eddie Chamblee also on tenor sax. The three tenors make a massive wall of sound that still excites the listener. According to the contract lists maintained by Musicians Union Local 208 during this period, in early June a group led by George Rhodes took up a residency at the Blue Heaven Lounge for 3 months. On the same date (June 6, 1946), "Edwin" Chamblee posted a contract for 2 weeks at the same venue. And Tommy Jones was a known quantity at the Blue Heaven, having performed there earlier in the year (his 3 week contract was accepted and filed on January 3; a 3-month contract followed on February 21). Around the time of the session he was working at the Band Box (1-week contract filed June 6) and Frank's Caravan (indefinite contract filed on the same day).

One of the vocal sides used on Miracle 101 is "Blues in My Heart," a superior ballad written by Benny Carter. It may have been George Rhodes who sought to evoke Carter's brilliant scoring with a lush arrangement for the three saxes (one of the tenorists—our guess is Eddie Chamblee—makes an unannounced switch to alto). The vocal line is affectingly handled by Savannah Strong. (She was mentioned, her first name mispelled, in the "launch" article in Billboard as being "inked"; the piece mentioned a second singer, Frances Holliday, who never had a release on Miracle.) "Tenor-Mental Moods" is a vigorous late-Swing instrumental based on "I Got Rhythm." There are solos for Dick Davis, Tommy Jones, and Eddie Chamblee (in that order) and the fast tempo leaves room for a little barrelhouse piano by Rhodes and some surprise bowing by Calhoun before the ensemble takes it out. The three tenors make an imposing ensemble whether riffing or playing the theme. A complete alternate take also survives.

Used on some other copies of 101 was "Sorry We Said Goodbye," featuring another vocal by Savannah Strong. This is a better than average lounge ballad, nicely sung, but the arrangement is much looser and the song is just not the equal of "Blues in My Heart." Davis does provide a ballad intro in the Coleman Hawkins tradition. The fourth, unissued side, "Ain't That Just like a Man," is a fast blues sung by Savannah Strong. The riffing is thrilling and Dick Davis provides a booting tenor solo with an uncharacteristic reed bite. It's too bad that they didn't extend the number, which clocks in under 2 1/2 minutes. Miracle would redo the piece, with extra verses and more instrumental interludes, as a vehicle for Gladys Palmer.

In September, Miracle recorded Rudy Richardson for the second time, but now the company was trying to position him as an R&B artist and the backing was provided by Dick Davis's band. George Rhodes had moved to New York City, where he got steady work in Arnett Cobb's combo. Sonny Thompson was now at the piano, along with Eddie Calhoun on bass, and probably Jimmie Hoskins on drums. "No Meat" is a humorous reaction to rationing that continued after the war (though other interpretations are simultaneously possible). Here Richardson (who exclaims "A steak! Why, man, you must be wiggin'," and makes the unsatisfactory offer of a "meatless stew" during the opening conversation), sings the lead and banters with the other members of the group. "No Meat" required 6 takes, on account of the complicated vocal exchanges; on one take a group member forgets the acronym for the Office of Price Administration. Davis and Thompson get a little solo space. "My Apartment" is a pseudo-Latin novelty number, apparently completed in one take. Vocally, it is mainly noteworthy for the sexual ambiguity of its lyrics; Davis and Calhoun (doing a passable imitation of the bowing and singing Slam Stewart) provide straightahead solos. If other sides were made on this date, they appear to be lost.

Rudy Richardson also recorded for the Manor label, using the standard piano-guitar-bass lineup (and Manor let him play piano on his dates). Of course, he may not have used the same bassist and guitarist as on his first Miracle session. Manor's headquarters were in Newark, New Jersey (later New York City) and its recording was generally done in the city, though in 1946 Manor was also recording another Chicago-based performer, singer June Davis. Manor 1039 coupled a medley of "They Raided the Joint" and "Route 66" with "A Stranger in Town" (we don't know the release date for 1039, but November 1946 is most likely). "Walkie Talkie" was used on Manor 1045 (a new release in Billboard, December 14, 1946, p. 34), with a flip by The Cats & The Fiddle. In addition, Rudy's Trio was credited in a Manor new release advertisement (Billboard, December 7, 1946) for accompanying Savannah Churchill on her big hit record, Manor 1046. Richardson plays celeste on both sides. On Manor 1047 by The Sentimentalists (who in a short while changed their name to the Four Tunes), there is accompaniment by a piano trio. According to Marv Goldberg, who has done detailed work on the Brown Dots and the Four Tunes (see http://www.uncamarvy.com/BrownDots/browndots.html), none of them played piano or bass, so the Rudy Richardson Trio was very likely on that release as well.

The sessions or sessions that produced Manor 1039, 1045, 1046, and 1047 took place in October (maybe also November, if there was more than one). We used to think they'd pre-dated Richardson's Miracles. Now that he had two Miracles and two and a half or three and a half Manors out, Rudy Richardson would sign a contract for 6 months at Kennedy's Honey Dripper Lounge (accepted and filed by Musicians Union Local 208 on January 16, 1947). Nearly a year later, a final Richardson Trio single appeared as Manor 1092 (this is the rarest of his Manors, and we haven't heard it). Trio accompaniment (and another switch to celeste behind Savannah Churchill) lead us to wonder about Manor 1093, which was split between Savannah Churchill on one side and the Four Tunes (the vocal group that she most often recorded with) on the other. Manor 1093 was reviewed in Billboard on November 1, 1947 (p. 116).

Richardson also worked the Flamingo Lounge ("One of 63rd Street's Gay Spots"). Now often spelling his first name "Rudi," Richardson appeared on two singles for the tiny Rim label; these were released in June 1949 and may have been recorded a couple of months earlier. He sang "If You Get It" and "You Made My Heart Cry Out" on Rim 100, and "Write Me a Letter" on Rim 101, to accompaniment by a solid jazz sextet led by one Bob Carter (confusingly, this was not the bass-playing Robert J. Carter who recorded for Specialty, Sunbeam, and Universal during this period). Richardson continued to appear fairly often in Chicago nightspots through the early 50s. He enjoyed a long residency at the Clover Lounge (he was in his 60th week there, according to Ted Watson, "Chicago Night Life Gets Lift from Name Artists," Pittsburgh Courier, September 12, 1953, p. 19) and another long residency at the Kitty Kat Club. In 1956, he participated in the opening of McKie's Disc Jockey Lounge.

1956 was also the year of his last recording. Richardson cut four sides in Nashville, most likely for Joe Johnson, the songwriting partner of Gene Autry, who was looking to start a new label featuring songs controlled by Autry's publishing company. In late 1956 or January 1957, with the new label not yet launched, either Joe Johnson or Troy Martin (the composer of "Why Should I Cry," who plugged songs for Autry in Nashville) pitched the session to Sam Phillips. In April 1957, Phillips put out "Fool's Hall of Fame" (a song he later had Johnny Cash and Roy Orbison record, with little success in either case; Cash's master was actually destroyed) and "Why Should I Cry"; the other two sides remained in the can. Although Sun 271 showed a small effort to update Richardson's sound, "Fool's Hall of Fame" still qualifies as torch material. (See http://www.boija.com for more about the Sun singles.) Rudy Richardson returned to Chicago on May 11, 1957, for the funeral of his (step)father, Cyrus Lockett, but was working primarily in Nashville, where from 1955 through 1958 he had several long runs at the Del Morocco lounge. On June 1, 1958, Richardson's body was found in a rooming house in Nashville, one block south of Fisk University. He had drunk denatured alcohol, very possibly with suicide in mind. (Our thanks to Colin Escott's liner notes to The Sun Rock Box 1954-1959, an 8 CD set on Bear Family 17313, for an updated and expanded bio on Rudolph Richardson, including details about his last recording session.)

On January 25, 1947, "Dick Davis and his swing combo" were still holding the fort at the Tradesmen's Lounge, according to the Defender. The rhythm section consisted of Sonny Thompson, piano; Eddie Calhoun, bass; and Jimmie Hoskins, drums. The caption claimed that the combo had recorded several numbers, including "Tenor-mental Moods." In fact, they had also backed Rudy Richardson, and would soon be cutting Davis's second session for Miracle. But it was Sonny Thompson who would end up selling a ton of records for Miracle; the company would not be recording Dick Davis again as a leader.

In early April 1947, Dick Davis moved out of the Tradesmen's, where he was replaced by Buster Bennett, and headed to Jimmy's Palm Garden, 808 Oakwood Boulevard. According to the caption on a photo of him that the Defender ran on April 26, his combo was participating in a Saturday battle of the bands series being broadcast over WGES (Al Benson's radio station) and would be up against "Linn's aggregation" (i.e., Claude McLin's group) the next day. In October 1947, Davis and his band were back at the Tradesmen's Lounge. When the band's engagement wound up on November 1, however, Matt Lightfoot, the owner, emptied the cash register and absconded; Davis had to press a claim against Ralph and Harold Lightfoot, who managed the place, with the Musicians Union for one week plus 3 days' pay (see Board meeting minutes to Local 208, November 20, 1947, p. 3).

Davis did get at least one more opportunity to record as a leader (see http://crownpropeller.wordpress.com/2011/12/26/dick-davis-combo-on-gateway-john-young-singing/). On April 16, 1949, Billboard announced (p. 51) that Ivan Ballen, the Philadelphia-based proprietor of 20th Century, Gotham, and other imprints, had been on a "Southern trip," leading to several artist signings to his Gotham label. A Defender ad from July 2, 1949 had Dick Davis and His Combo headlining at the "Q" Lounge, 114 East 43rd Street. The rhythm section consisted of Johnny Young, piano; Eddie Calhoun, bass; and Buddy Smith, drums. This was the same lineup that appeared on Gotham 182, a single most likely released in July or August 1949 with vocals by the leader on both sides. John Young later recalled that he had also done some singing during the gig at the "Q" (in later years, he would beg off requests for vocals, claiming to have laryngitis).

Possibly in 1952, another single by the same Dick Davis quartet (featuring blues singing by John Young on one side, and a composer credit to all four band members on the others) would appear on Gateway 5001. This was almost certainly derived from the Gotham session, though the chain of transactions (more than one could have been shady) that brought it to Gateway remains to be established. Gateway was a Cincinnati-based label, specializing in 49-cent singles, that also released a couple of other "race" items, including 5002 by Jump Jackson. It put out a lot of other material, but was best known for its Country sides. In April 1950, the Dick Davis Combo was holding forth at the Corner Lounge (1900 West Lake), in a variety show format that included Grant "Mr. Blues" Jones (see the Chicago Defender, April 29, 1950, p. 34).

From September 1951 until he became ill at the beginning of 1954 Dick Davis was a regular member of the King Kolax combo, which brought him a few more recording opportunities. On January 19, 1954 he died after a three-day battle with lobar pneumonia. (His obituary ran in the Chicago Defender on January 30, unfortunately with an incorrect date of death). Dick Davis was only 36.

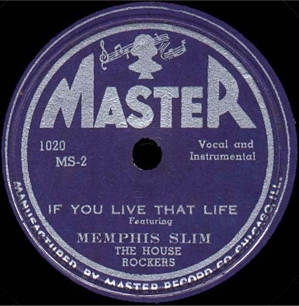

Blues pianist Memphis Slim was among the most prolifically recorded of Miracle's artists. He was born John L. Chatman (not Peter Chapman Jr. as many sources say) on September 3, 1915, in Memphis. In 1939 he moved to Chicago, and in 1940 made his first recordings, for OKeh, under the name Peter Chapman. (Meanwhile, the Musicians Union local knew him as Peter Chatman.) He recorded for Bluebird in 1940 and 1941 as Memphis Slim. From 1940 to 1944, and occasionally in 1945 and 1946, he was teamed up with Big Bill Broonzy. After several years away from the studios, he recorded with two different trios for Hy-Tone in late 1945 or early 1946. He also made a non-commercial recording (as much talk as music) with Big Bill and John Lee "Sonny Boy" Williamson in New York City, probably in the summer of 1946; it was released years later on a United Artists LP. He joined Miracle in the fall, cutting his first session for the label in October. During this period he was a mainstay at the South Side's preeminent blues club, the Flame Lounge (3020 Indiana Avenue). For instance, on November 7, 1946 Slim's contract for another 3 months at the Flame was accepted and filed by Musicians Union Local 208. Miracle had the happy idea of recording him with two saxes and string bass, in an ensemble that was eventually dubbed the House Rockers. Slim's piano style included elements of boogie-woogie and traditional blues, and the House Rockers, driven by fervent riffing from the alto and tenor sax, helped to transform his music into rhythm and blues.

Slim's quartet on his first session for Miracle included Alex Atkins on alto saxophone, Ernest Cotton (1926 - ) on tenor—both had come to Chicago from Memphis—and Willie Dixon (1915 - 1991) on string bass.

Dixon, whose usual gig at the time was with the Big Three Trio, contributes to the conversation that opens "Kilroy Has Been Here." (On the first two takes, Slim actually addresses him as "Big Three.") It took five attempts to properly coordinate Slim and Dixon's alternating shouts of "Kilroy!" with the continuation "have been here and gone." The rousing boogie "Rockin' the House," which ended up giving Slim's group its name, achieved takeoff after one false start. At this point in the group's evolution, Alex Atkins was the major soloist after the leader—he can be heard to advantage on "Kilroy" and "Rockin'." Ernest Cotton also gets a solo on "Rockin'." The two vigorous numbers are counterbalanced by the pensive "Lend Me Your Love" and the brooding "Darling I Miss You," each of which needed just one take. All four numbers from this classic session were promptly released, selling well enough to bring Slim and his ensemble back for no fewer than five follow-up sessions in 1947.

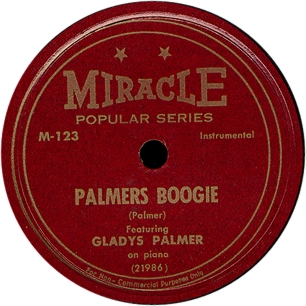

Jazz singer Gladys Palmer was profiled in Sharon A. Pease's column in Down Beat, July 14, 1947. She told Pease that she was born in Kingston, Jamaica (misrendered by Down Beat as "Kensington"), and came to America at the age of seven to attend boarding school in Atlanta. Her mother was a talented vocalist and pianist and taught young Gladys piano. In the States, she continued to develop her pianistic skills, and cited her influences as Duke Ellington and Fats Waller. (Accompanying the Pease profile was her boogie woogie composition, "Palmer's Boogie," which formed the flip of her second Miracle release.) She began performing professionally while still in high school. She was enjoying a long run at Atlanta's Biltmore Hotel when she was discovered by J. Mayo Williams and Dave Kapp of Decca Records. They brought her to Chicago to record a solo session in 1935, followed by a legendary appearance with Roy Eldridge in 1937. Palmer made her home in Chicago, and played a long run at the Three Deuces. From 1937 to 1940, she worked the clubs in New York, then returned to Chicago. (Recent research by Marv Goldberg shows that much of what Palmer told Pease was a complete fabrication. When his bio is completed, we will make the necessary corrections here.)

From 1942 to 1946, Palmer was based in Hollywood (also unlikely to be true), though she made trips to Chicago from time to time (for instance, on October 7, 1943, her contract for 1 week at the Latin Quarter was accepted and filed by Musicians Union Local 208). She returned to the Windy City in time to produce Miracle's first national hit.

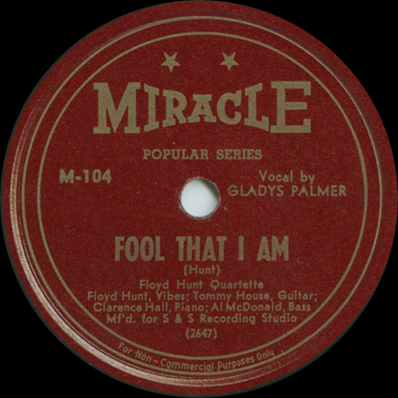

Palmer recorded "Fool That I Am" (Miracle 104) as the vocalist on the Floyd Hunt Quartet session in October 1946. With slender resources, Miracle didn't release it until May 1947. By August, it was starting to move, and the ballad standard went to the lofty #3 position on Billboard's Race Jukebox chart in the fall of 1947. Her other vocal side, "Ain't That Just like a Man," was eventually released, but only after Miracle had gone out of business.

A classic torch song, "Fool That I Am" was initially done so slowly the first completed take ran to 3 minutes and 58 seconds. This made it a poor candidate for uncut release on a 10-inch 78. After a brief introduction, the first take went straight into Palmer's vocal. She sang the entire song, there was a long guitar solo, and then Palmer reprised the song at "Fool that I am, I thought you would understand." Despite the availability of the shorter take 2, Egalnick and Simpkins obviously preferred take 1. It underwent surgery. Palmer's complete rendition of the song was cut starting at "Fool that I am, I thought you would understand"; so was the ensuing guitar solo. Instead the remastered side picked up with her vocal reprise and ended as take 1 had originally done. To our knowledge all releases of take 1 have been as edited.

The second completed take, which featured a 45-second solo on the vibes before the vocal, was just a hair faster, but it ended with the vocal chorus. At 3:05 or so, take 2 was easily mastered uncut for a 10-inch 78. It was eventually released, on a Federal 78 after Miracle closed down. Federal had both takes in its possession, so there must have been a deliberate decision somewhere.

The Floyd Hunt group consisted of Hunt (vibes), Tommy House (guitar), Clarence Hall (piano), and Al McDonald (bass). The release was credited to the "Floyd Hunt Quartette" with Gladys Palmer indicated as the vocalist. The flip side, "Harlem Breakdown," was a moderate boogie instrumental that prominently featured Hall's two-fisted piano, House's rocking guitar, a Hamptonesque solo by Hunt, even an interlude for McDonald. Two sides were left unissued. "Ain't That Just like a Man" (the same piece previously recorded by Savannah Strong with Dick Davis) was an uptempo blues feature for Gladys Palmer, with plentiful solo space for Hunt and House. But the success of "Fool That I Am" apparently ruled out further efforts at R&B from the singer. Meanwhile, "I'll Get By" was a Swing performance by an older male vocalist with some ensemble vocal accompaniment. The vibes fall silent after the Hamp-style solo that precedes the vocal, so the singer was Floyd Hunt himself.

Meanwhile, Palmer was also generating considerable notice during 1947 at the Monte Carlo, playing a 24-week engagement. Said the Chicago Defender in April, "Miss Palmer who handles the spot's entertainment program was grabbed from the Loop several months ago and has become a fixture at the hot spot. Her singing and fine piano plucking attracts large crowds from the Loop district nightly and is the reason for the lounge being the gathering place for musicians from theatres and other places on the southside and the Loop."

Although Gladys Palmer landed Miracle a hit, her style of singing did not have lasting appeal with the record-buying public. The company brought her back into the studio on several occasions as 1947 wound down, probably recording much of her active repertoire, but her later singles did not sell well and much of her work for Miracle has never seen release.

When Miracle signed Brother John Sellers in 1946 he had already built careers in both blues and gospel singing. He was born May 27, 1924 in Clarksville, Mississippi, and moved to Chicago as a youngster. In the early 1940s he was mentored by Mahalia Jackson. He recorded both blues and gospel for Mayo Williams' Chicago label during 1945. His first session for Miracle consisted of 4 gospel numbers, including Mahalia's signature song, "Move On Up a Little Higher."

On Miracle 106 and 107 the accompaniment on vibes, piano, and bass were provided by Floyd Hunt and two of his musicians, Clarence Hall and Al McDonald. Hunt adapted to the gospel setting by cranking the motor on his vibes way up (as he had already done on "Fool That I Am") and playing sweetly to approximate the sound of an organ, while Hall provided rather stiff elementary accompaniment on the piano. (The sweetness and the clunky pianistics can be heard on "Precious Lord," which McDonald joins only on the final chord. Hunt does work jazzy runs into "Move On Up.") On "Beginning of Sorrow," a remarkably jaunty tune considering its references to "the last days," which also gives Hunt ample solo space, Sellers can be heard using the folk pronunciation "Norah" for Noah. The more reverential "Just Wait a Little While" cuts back to just Hunt and McDonald in accompaniment. The unorthodox backing was reasonably effective, and Sellers sang soulfully in a pleading tenor voice, but one wonders how the sides did in the marketplace.

The unusual instrumentation behind Sellers, the consecutive matrix numbers—and the fact that Floyd Hunt's last and Memphis Slim's first track sit next to each other on the same 16 inch acetate—indicate a ganged session for Hunt's group, Memphis Slim, and Brother Sellers on the same day.

In 1947 Sellers recorded a blues session for RCA Victor. In late 1948, as Rev. John Sellers, he returned to Miracle for another gospel session. After two Chance blues sessions in 1952 (he was billed as "Johnny" Sellers for these), Sellers moved to New York and became involved in the folk club scene, recording albums that included blues, gospel, and folk stylings. Sellers died on March 27, 1999.

For Miracle, 1946 was a year of dipping toes into the water. Total output was 26 sides. Just 4 singles were released before the end of the year: the two blue-label Miracles by Rudy Richardson, and red-label Miracle 100 and 101.

| Matrix | Artist | Title | Release # | Recording date | Release date |

| UB 2196 [tk. 2] | Dick Davis Sextette | Vocal by Savannah Strong | Ain't That Just like a Man | unissued | 6/1946 | |

| UB 2197 [tk. 1] | Dick Davis Sextette | Dick Davis, Tenor; T. Jones, Tenor; E. Chamblee, Tenor; George Rhodes, Piano; E. Calhoun, Bass; Little Jimmy, Drums | Tenor-mental Moods | Miracle 101 | 6/1946 | 12/1946 |

| UB 2197 [tk. 2] | Dick Davis Sextette | Tenor-mental Moods | unissued | 6/1946 | |

| UB 2197 [tk. 3 - inc] | Dick Davis Sextette | Tenor-mental Moods | unissued | 6/1946 | |

| UB 2198 [tk. 1 - fs] | Dick Davis Sextette | Vocal by Savannah Strong | Blues in My Heart | unissued | 6/1946 | |

| UB 2198 [tk. 2] | Dick Davis Sextette | Dick Davis, Tenor; T. Jones, Tenor; E. Chamblee, Tenor; George Rhodes, Piano; E. Calhoun, Bass; Little Jimmy, Drums | Vocal by Savannah Strong | Blues in My Heart | Miracle 101 [some copies] | 6/1946 | 12/1946 |

| UB 2199 | Dick Davis Sextette | Vocal by Savannah Strong | Sorry We Said Goodbye | Miracle 101 [some copies] | 6/1946 | 12/1946 |

| 1057-S (A-5187) | Rudy Richardson and Ted Craig Piano - Eddie Calhoun Bass - Lefty Bates Guitar | Hick-Botham | Miracle 1057/1059 | 6/1946 | 8/1946 |

| 1058-S (A-5188) | Rudy Richardson and Ted Craig Piano - Eddie Calhoun Bass - Lefty Bates Guitar | I'm Turning in My Chips | Miracle 1058/1060 | 6/1946 | 8/1946 |

| 1059-S (A-5189) | Rudy Richardson and Ted Craig Piano - Eddie Calhoun Bass - Lefty Bates Guitar | Chauffeur | Miracle 1057/1059 | 6/1946 | 8/1946 |

| 1060-S (A-5160) | Rudy Richardson and Ted Craig Piano - Eddie Calhoun Bass - Lefty Bates Guitar | I Need You | Miracle 1058/1060 | 6/1946 | 8/1946 |

| 1152SS [alt tk. 1] | Rudy Richardson | No Meat | unissued | 10/1946 | |

| 1152SS [alt tk. 2] | Rudy Richardson | No Meat | unissued | 9/1946 | |

| 1152SS [alt tk. 3] | Rudy Richardson | No Meat | unissued | 9/1946 | |

| 1152SS [alt tk. 4] | Rudy Richardson | No Meat | unissued | 9/1946 | |

| 1152SS | Rudy Richardson | No Meat | Miracle 100 | 9/1946 | 12/1946 |

| 1152SS [alt tk. 5] | Rudy Richardson | No Meat | unissued | 9/1946 | |

| 1154SS | Rudy Richardson | My Apartment | Miracle 100 | 9/1946 | 12/1946 |

| UB2646 [tk. 1] |

Floyd Hunt Quartettte (vocals: Gladys Palmer) | Ain't That Just like a Man | unissued | c. 10/46 | |

| UB2646[tk. 2] [F1012] |

Floyd Hunt Quartette (vocals: Gladys Palmer) | Ain't That Just like a Man | [Federal 12006] | c. 10/46 | [c. 3/1951] |

| UB2646 [tk. 3 - inc] |

Floyd Hunt Quartette (vocals: Gladys Palmer) | Ain't That Just like a Man | unissued | c. 10/46 | |

| 2647 [tk. 1] (UB2647SS-1 in wax) |

Floyd Hunt Quartette (vocals: Gladys Palmer) | Fool That I Am | Miracle 104 [edited] | c. 10/46 | 5/1947 |

| 2647 [tk. 2] [F-1030] |

Gladys Palmer | Vocal: Gladys Palmer | Fool That I Am | [Federal 12018-AA] | c. 10/46 | |

| 2648 [tk. 1] | Floyd Hunt Quartette | Harlem Breakdown | unissued | c. 10/46 | |

| 2648 [tk. 2] (UB2648SS in wax) |

Floyd Hunt Quartette | Harlem Breakdown | Miracle 104 | c. 10/46 | 5/1947 |

| 2649 [tk. 1] | Floyd Hunt Quartette (vocal: Floyd Hunt) | I'll Get By | unissued | c. 10/46 | |

| 2649 [tk. 2] | Floyd Hunt Quartette (vocal: Floyd Hunt) | I'll Get By | unissued | c. 10/46 | |

| UB2650 [tk. 1 - inc] | Memphis Slim Quartette | Kilroy Has Been Here | unissued | c. 10/46 | |

| UB2650 [tk. 2 - inc] | Memphis Slim Quartette | Kilroy Has Been Here | unissued | c. 10/46 | |

| UB2650 [tk. 3 - inc] | Memphis Slim Quartette | Kilroy Has Been Here | unissued | c. 10/46 | |

| UB2650 [tk. 4 - inc] | Memphis Slim Quartette | Kilroy Has Been Here | unissued | c. 10/46 | |

| UB2650 [tk. 5] | Memphis Slim Quartette | Kilroy Has Been Here | Miracle 102 | c. 10/46 | c. 1/1947 |

| UB2651 [tk. 1 - fs] | Memphis Slim, Piano; Alex Atkins, Alto Sax; Ernest Cotton, Tenor Sax; Willie Dixon, Bass. | Rockin' the House | unissued | c. 10/46 | |

| UB2651 [tk. 2] (some copies have 2651 on label, 2651SS in wax) |

Memphis Slim, Piano; Alex Atkins, Alto Sax; Ernest Cotton, Tenor Sax; Willie Dixon, Bass. | Rockin' the House | Miracle 103 | c. 10/46 | 5/1947 |

| UB2652 (some copies have 2652 on label, 2652SS in wax) [F1047] |

Memphis Slim, Piano; Alex Atkins, Alto Sax; Ernest Cotton, Tenor Sax; Willie Dixon, Bass. | Lend Me Your Love | Miracle 103 [Federal 12033] |

c. 10/46 | 5/1947 |

| UB2653 [F1046-1] |

Memphis Slim Quartette | Darling I Miss You | Miracle 102 [Federal 12033] |

c. 10/46 | c. 1/1947 |

| 2654 [tk. 1] | Brother Sellers | Vibraharp - Piano - Bass | Precious Lord | unissued | c. 10/46 | |

| 2654 [tk. 2] | Brother Sellers | Vibraharp - Piano - Bass | Precious Lord | unissued | c. 10/46 | |

| 2654 [tk. 3] | Brother Sellers | Vibraharp - Piano - Bass | Precious Lord | Miracle 106 | c. 10/46 | prob. 5/1947 |

| 2655 [tk. 1] |

Brother Sellers | Vibraharp-Piano-Bass | Move On Up a Little Higher | unissued | c. 10/46 | |

| 2655 [prob. tk. 2] (UB2655 SS in wax) |

Brother Sellers | Vibraharp-Piano-Bass | Move On Up a Little Higher | Miracle 107 | c. 10/46 | prob. 5/1947 |

| 2656 [tk. 1 - fs] | Brother Sellers | Vibraharp - Piano - Bass | Beginning of Sorrow | unissued | c. 10/46 | |

| 2656 [tk. 2] | Brother Sellers | Vibraharp - Piano - Bass | Beginning of Sorrow | unissued | c. 10/46 | |

| 2656 [tk. 3 - inc] | Brother Sellers | Vibraharp - Piano - Bass | Beginning of Sorrow | unissued | c. 10/46 | |

| 2656 [tk. 4 - inc] | Brother Sellers | Vibraharp - Piano - Bass | Beginning of Sorrow | unissued | c. 10/46 | |

| 2656 [tk. 5] | Brother Sellers | Vibraharp - Piano - Bass | Beginning of Sorrow | Miracle 106 | c. 10/46 | 1947 |

| 2657 (UB2657 SS in wax) |

Brother Sellers | Vibraharp-Bass | Just Wait a Little While | Miracle 107 | c. 10/46 | 1947 |

The first sides recorded in 1947, probably in January, were by the Dick Davis Orchestra featuring Sonny Thompson. The personnel as listed by Walter Bruyninckx were Dick Davis on tenor sax; Eddie Chamblee on tenor sax and vocals; Tommy "Mad Man" Jones on tenor sax and vocals; Sonny Thompson on piano; Lefty Bates on electric guitar; Eddie Calhoun on bass; and Buddy Rich on drums. (The Dave Penny story on Sonny Thompson, "Screaming Boogie," published in Blues & Rhythm, gives Buddy Smith on drums, which rather strongly suggests that "Buddy Rich" is a mistype, and says that Bates is inaudible.)

Bruyninckx and subsequent disocgraphers were way off. There was only one tenor saxophonist on Miracle 108 and 109: Dick Davis himself (thanks to Tom Kelly and Daniel Gugolz for confirming this). Jones and Chamblee were incorrectly carried over from the June 1946 session. And the rhythm section was misidentified as well. The band that was playing the Tradesmen's Show Lounge in late January of 1947 featured Davis on tenor sax, Thompson on piano, Jimmie Hoskins on drums, and Eddie Calhoun on bass. The caption to a wonderful photo of the group in action says, "The combo, shown above, has recorded several numbers, including 'Tenor-Mental Moods' that are hit parade material." ("Tenor-Mental" had been recorded the previous year, with George Rhodes at the piano.) In February the outfit was billed as "Dick Davis Combo, featuring Sonny Thompson, Savannah Strong on vocals." Meanwhile, on March 12, 1949, the Defender stated that Dick Davis and his combo had just come back from a three-month stand in Cincinnati at the Sportsman Club, and was opening March 14 for a long engagement at the Congo Club. The personnel for that group was John Young on piano, Eddie Calhoun on bass, and Buddy Smith on drums. Clearly, Jimmie Hoskins and not Buddy Smith was the drummer on the January 1947 session.

For the second session, Miracle kept on with the trend set by the second Rudy Richardson session, pushing the Davis ensemble away from Swing and into R&B. A copy of Miracle 109 in the late Otto Flückiger's collection reveals an ensemble vocal (a common device on Miracle releases). Typical of the period, Miracle 109 was a recording designed to get the powerful deejay Al Benson to play the company's records. On "Benson Jump" an ensemble vocal (three males, including Sonny Thompson who sings the bridge by himself, with obbligato by Dick Davis) sing about the joys of jivin' to the music played by Al Benson; the flip is a dramatization of two travelers, a porter, and a lady on the train from Chicago to Memphis.

According to Dave Penny, Sonny Thompson was the featured vocalist on "Sonny's Blues" from this session. Aside from some bantering on Rudy Richardson's "No Meat," and contributions to the ensemble vocals on "Benson Jump" and "Memphis Train" from this session, it would be the first time his voice was heard on a record. However, Miracle would make only sparing use of Thompson's vocal talents during his residency with the company; when one of his vocal sides saw release, Thompson wasn't creditd on the label.

A May issue of Billboard reported that "Miracle Records, independent race label, has started sponsoring a 15-minute disk jock spot by Al Benson weekly over WGES." The item also discussed how the firm was building up its distribution net, adding distributors in Dallas, Houston, Birmingham, Jackson. Miss., and Cleveland.

Memphis Slim continued his work for Miracle with four more sessions in 1947 (his band backed Lillie Mae Kirkman on a fifth). His quartet continued to feature Alex Atkins (alto sax) and Ernest Cotton (tenor sax). Charles Jenkins played the string bass on the first session; after that the chair was occupied by Ernest "Big" Crawford, whose trademark string-snapping could also be heard on more down-home sessions by Sunnyland Slim and Muddy Waters. Slim took up residence at the Hollywood Lounge in January 1947 (indefinite contract accepted and filed by Local 208 on January 16). Around the end of April he moved his group into the Timber Tap (indefinite contract posted on May 1).

The first session (which included the invigorating "Pacemaker Boogie" and the reflective "Life Is like That") took place around March 1947, in time for the third and final launch of Miracle Records that took place in May. After that the band didn't return to the studio until October. By then, though, the "recording ban" had been announced for January 1, 1948, and the company was eager to stockpile Memphis Slim slides. So several further visits followed before the end of the year.

Memphis Slim gave Miracle a #1 national hit in the spring of 1948 with the reflective "Messin' Around" (Miracle 125), which was recorded in December of 1947. Interestingly, the composition was credited to another Miracle artist, pianist and vibraphonist Floyd Hunt, whose work would occasionally surface on Slim's later sessions. The flip of Miracle 125, "Midnight Jump" is, unusually for Slim, a late Swing number with strong solos by Alex Atkins and Ernest Cotton. Slim has no trouble with the idiom; it's just not what Miracle's customers most wanted to hear. Miracle 125 was on the regional Cash Box charts for several months in 1948; the company apparently didn't submit the single for review because it started selling right away. Recorded at the end of October 1947 were "Blue and Lonesome" (Miracle 136) and "Angel Child" (Miracle 145), both of which made the national R&B charts in 1949. Miracle was able to mine a deep Memphis Slim catalog throughout the history of the label.

The flip side of "Angel Child" deserves some notice as well. Under the title "Nobody Loves Me," it was Memphis Slim's first recording of "Every Day I Have the Blues." (A second take of "Nobody Loves Me," also apparently cut in October 1947, has survived and can be heard on Memphis Slim: The Complete Recordings Vol. 2 1946-1948 on Blues Collection CD 159862. Vol. 3 1948-1950 in this most valuable series, Blues Collection CD 160142, includes Slim's Miracle recordings from "Midnight Jump" onward, includes the four sides that were taken over by Master, and continues through his first session for Premium.) Slim claimed writing credit (and often got it on subsequent releases) but in fact the tune was first recorded, under its usual title, back in 1935 by Aaron "Pinetop" Sparks for Bluebird. The celebrated 1952 version by Joe Williams with King Kolax could have been inspired by either Slim's "Nobody Loves Me" or Lowell Fulson's 1950 hit version under the "Every Day" title.

Miracle also recorded local blues singer Lillie Mae Kirkman, who appeared as plain old "Lillie Mae" on two sides with Memphis Slim's House Rockers, "Lovin' Man Blues" and "Lonesome." Each was apparently cut in one take during a session around December 20. (Another couple of Memphis Slim tracks that have lost their original UB numbers could have been done at this same session.) Released on Miracle 129 in November 1948, the two sides retained too much of the old "Bluebird beat" to attract buyer interest. The slow "Lovin' Man" features a thoughtfully lyrical tenor sax solo by Ernest Cotton. The perkier "Lonesome" makes good use of the House Rockers' sax riffing and Big Crawford's string slapping.

A singer out of the Victoria Spivey school, Lillie Mae had previously recorded twice in 1939. Her first session was made for Bluebird in May 1939 under the pseudonym of Ramona Hicks. It featured Buster Bennett on alto sax, and full details can be found on his page. (An item in the Chicago Defender for June 17, 1939 refers to one Ramona Hicks, originally from St. Louis, "who is also known as Lillie Mae Kirk.") In July 1939 she made a session for Vocalion, with accompaniment by pianist Curtis Jones and guitar Hobson "Hot Box" Johnson. Now billed as Lillie Mae Kirkman, she had two discs released (these featured such family-values titles as "Hop Head Blues"; another titled "He's Just My Size" has been featured on several latter-day packages of blues with bawdy lyrics). Kirkman spent much of the 1940s singing at Martin's Corner (1500 West Lake) on the West Side, often backed by the Jump Jackson band. She was variously called Kirkman, Kirkmond, Kerkmond and Kirkland in Defender ads and items. Maybe Egalnick threw up his hands and avoided the quandary by leaving her last name off the label. Though often billed as "Queen of the Blues," Kirkman obviously built her reputation as a local club performer. These were in fact her last performances on record.

One of the sides on Lillie Mae's Miracle release is credited to John E. Coppage, a songwriter and record producer who had some kind of association with United Broadcasting Studios. Coppage's relationship with Miracle may have been casual, but we know that he freelanced at the studio (for instance, when he recorded two sessions with guitarist Floyd Smith at UB in 1949, later selling one of them to Aristocrat.)

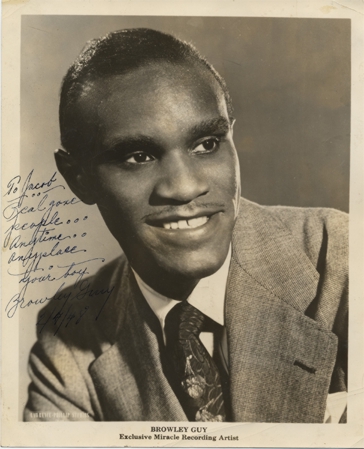

In August 1947, Miracle recorded the first of six sessions featuring a singer named Browley Guy. Possessed of a smooth baritone instrument, Browley Guy graduated from Wendell Phillips High School in June 1936, which means he was probably born in 1918 or 1919 (we will be upgrading our bio to take advantage of Marv Goldberg's reseearch on the singer). Guy served in the Army during World War II, posted to Fort Huachuca in southern Arizona. Browley Guy and his Fort Huachuca Quartet were among the performers when an army chaplain was honored for his service ("Chaplain Hodge To Be Honored: Being Given Certificate Today in Recognition of Services," Arizona Daily Star [Tucson], March 19, 1944, p. 12). Some months later, Private Browley Guy was part of a vocal sextet that appeared in several Arizona towns as the 5th War Bond Cavalcade ("Huachuca Personnel Participates in Bond Selling Cavalcade," New York Age, August 12, 1944, p. 7). One of the other members was "Call Cobb, jr." In other words, Harvey Call Cobbs, Jr., the pianist from Ohio who resurfaced many years later with Albert Ayler. In May 1946, Guy was in the Swingaroo revue at Smalls' Paradise in Harlem (New York Age, May 11, 1946, p. 11). The Pittsburgh Courier ventured to declare that Guy, whose next booking was at Bali in Washington, "has one of the best male voices this side of Billy Eckstine" (June 1, 1946, p. 16). Not quite. We are not sure where in Chicago Guy was working when Lee Egalnick and Lew Simpkins picked him up. Much was expected from him, but his first session, which featured Sonny Thompson at the piano with an otherwise unknown band, was held back.

The company would record Guy again in October, with his vocal group The Skyscrapers and a band led by Eddie Chamblee. Miracle was much happier with these items, releasing "Certain Other Someone" and "Last Call" (an instrumental) in December 1947 and bringing out "Knock Me a Zombie" at some point during the next year and a half.

Before 1947 was out, Guy appeared on two more sessions with Sonny Thompson and the Sharps and Flats; one of his vocal sides from the first session would see release. "That Gal of Mine" is partly redeemed by Thompson's Wilsonian piano and a few splashes of vibes from Floyd Hunt. But "For the First Time," a solo vocal from the early December session, is pretty dire, and "Just Can't Fool Myself," which exists in at least four takes (two from around November 27 and two from early December) didn't get any better with practice. Guy's faithful clientele in the clubs never translated into record sales, so most of his tracks were left unissued.

There is little prospect of reviving them now. For today's listener, the lounge ballads of the late 1940s are what has badly dated, and lounge ballads, crooned sweetly, were what Guy most often recorded. He didn't treat slow standards much better. But when Miracle let him do a jump, he and his mates in the Skyscrapers took care of business. "Knock Me a Zombie" is a hip late Swing number (complete with a little Swing scatting, and a reference to Duke Ellington on the jukebox). Unfortunately it is one of just two such pieces that Miracle recorded. The other jump, which celebrates the "Man from Timbuktu" (who, despite his exotic origins and large shoe size, wears a "zoot suit with a reet pleat"), was left in the vault. There is further evidence, from their February and August 1952 session for States, that Guy (who got some help on States from his brother Slim) could sing blues and jumps respectably.

Guy and group would get two further opportunities to record, for Al Benson in June 1953 (leading to one single on Checker), and for Mercury, for a release in January 1956. By the time of their Mercury session, which was meant to compete with the work of much younger doowop groups, the Skyscrapers sounded extremely dated. Browley Guy kept going as a solo artist; he snagged a session with Vee-Jay in 1963. So far as we know, Vee-Jay 541, an extremely rare 45-rpm single, was his last release. In fact, the only photo we've been able to find is of a DJ copy.

In October 1947, the company brought the great tenor saxophonist Eddie Chamblee, who had appeared on the first Dick Davis session, back into the studio as a leader. Edwin Leon Chamblee was born in Atlanta, Georgia, on February 24, 1920. He attended Wendell Phillips High in Chicago, where he was a classmate of Ruth Jones (1924 - 1963, better known to posterity as Dinah Washington). While in the Army during World War II he became deeply involved in music, and after the war he joined the Lionel Hampton Orchestra, touring with the band for two years.

The October 1947 session uses accompaniment by a piano, guitar, and bass trio. Chamblee makes the most of his limited opportunities on the two vocal ballads from the date and shines on the jump ("Knock Me a Zombie"). And "Last Call" is a booting instrumental that should have encouraged Miracle to bring Chamblee right back into the studio without a vocalist. Miracle 119, a December 1947 release which coupled one of the vocal group ballads with the instrumental, did not sell well. (Another drippy ballad, titled "On the Blue Side," was never released.) Chamblee's big break would come just a little later, out of his work as a sideman on several of Sonny Thompson's sessions.

Miracle scored its biggest hit in the spring of 1948 with keyboardist Sonny Thompson's great rolling instrumental, "Long Gone." Like so many other things, it was recorded during the last quarter of 1947 while the company was feverishly stockpiling sides in anticipation of "B-Day." (B-Day was the Petrillo-led "recording ban" that went into effect on January 1, 1948.) On Part 1, the record featured Thompson on piano and Arvid Garrett of the Sharps and Flats on guitar; tenor sax player Eddie Chamblee took over for Part 2. The two parts actually came from different sessions. Part 1 was done at Thompson's second session, in early November, while part 2 had to wait for his third session toward the end of the same month). The relaxed rhythm behind the pair was maintained by the Sharps and Flats, namely Arvid Garrett (guitar), Leroy Morrison (bass), and Thurman "Red" Cooper (drums). The Sharps and Flats had been working the clubs for some time on their own when Miracle teamed them up with Thompson (who at this point in his career often worked as a solo pianist). The Sharps and Flats did a lot of harmony singing on their club gigs; however, Miracle was not initially interested in this aspect of their work. (Sharps and Flats vocals would be featured on a session with Sonny Thompson around December 22, 1947 and, at greater length on a session they shared with Eddie Chamblee around July of 1948, but the company never released any of them.)

The company brought Sonny Thompson into the studio in August, primarily to back Browley Guy on two ballads. Nothing from the session was ever released. Thompson brought in a guitarist and a bass player; a violinist can also be heard on "I Live to Worship You." Despite some interesting solo work by the pianist, the performance is lugubrious and syrupy and the instruments sound as though they're being played in somebody's living room. "Out of Nowhere" is a far better song, the violinist is now approximately in balance with the other musicians, and Sonny Thompson pulls out all of his Teddy Wilson and Art Tatum tricks—but Guy's drippy vocal, marred by tasteless scoops and slides, is hard to bear. After the two vocal tracks were completed, the violinist was sent packing and Thompson turned in a Tatumesque performance of "Just You, Just Me" that cries out for reissue.

Undaunted by this false start, Miracle began to get the results that it wanted when Thompson and the Sharps and Flats came into the studio in October to back Gladys Palmer. A vibraphonist, probably Floyd Hunt, was added on the two of the numbers. "Strangest Feeling," "I Understand We're Through," and "If It's Love" were strong ballad performances. "I'm Pullling Through" is Palmer's tribute to Billie Holiday. Palmer and Thompson brought a lighter touch to "S'posin'," which seems to have been too much of a Swing number to interest Miracle's management.

In November, Thompson and company made "Long Gone Part 1" in a session that mostly featured the vocalist once again. Gladys Palmer's ballad performance on "If I Didn't Have You," which was issued in December 1947, before "Long Gone," adds vibes, again by Floyd Hunt; the flip, "Palmer's Boogie," credits Palmer for playing piano.

Around a week later, Gladys Palmer returned to the studio to lay down more ballads. "In the Rain," credited on the label to freelance producer John Coppage, is one of her better ballad vehicles, with Tatumesque accompaniment by Sonny Thompson and splashes of vibes from Floyd Hunt. "Forget It" picks up the tempo a little and gives Thompson and the Sharps and Flats some interesting things to do (check out Sonny's introduction to the second take), but the song is nothing special. Nor is "You're Getting Me Down," another fairly slow ballad, despite Thompson's Wilsonesque accompaniment. A real curiosity, worked in at the end of the session, is "Heartaches"—the first item that Miracle chose to record with just the Sharps and Flats. It features whistling by one member of the trio.

Providing further evidence that Egalnick and Simpkins needed time to discover what Sonny Thompson could do for them, "Long Gone Part 2" was made around November 27, at the tail end of a session on which Thompson's group backed Browley Guy and his vocal group. The combo's ebullient contributions to "Man from Timbuktu" suggested that something special might be in the offing, but Guy and company's two ballads called for nothing more than calm professionalism. "Long Gone Part 2," however, proves that the decision to add Eddie Chamblee's tenor sax to Thompson and the Sharps and Flats gave Part 2 the precise touch that it needed.

Miracle was now seeing a lot of commercial potential in Sonny Thompson, for the company brought him back into the studio seven times during the stockpiling period in December. The first, around December 7, consisted mostly of solid instrumentals with Eddie Chamblee and the Sharps and Flats. "Walkin'" and "Late Freight" were blues, while "Bounce" and "Devil Grape" were Swing numbers out of Hines, Wilson, Tatum, and Basie. Only "Late Freight" would see release while Miracle was in business.

Particularly noteworthy is the session from around December 16, when Sonny, Eddie Chamblee, and the Sharps and Flats got to lay down four instrumentals without any vocal distractions. They obliged with two tasty Swing originals, "Sonny's Special" and "Tip Lightly," and a Jacquet-style romp on "Sweet Georgia Brown" featuring Chamblee. Miracle used nothing but the eloquent "Blue Dreams," whose genre is obvious from the title: Chamblee, Garrett, and Thompson are the soloists. It required two complete runthroughs only because of some cutting faults on take 2.

The session of December 19, or thereabouts, caught Gladys Palmer apparently suffering from laryngitis. She turned in two affecting takes of "Once You Were Mine," on which her hoarseness was already audible. But after that she either had to quit singing—or she should have, and her sides were rejected by the company. On "I Really Did," a pretty good male vocalist took over—Sonny Thompson, doing his first ballad for Miracle. At the end of the session, Palmer essayed a runthrough of "Don't Be That Way" (a lounge ballad unrelated to the Swing instrumental by that name); she finished the song, hoarser than ever. Nothing from the session was released, and the company had to try again with Palmer less than two weeks later.

A session around December 22 finally gave the Sharps and Flats a chance to show off their group vocals. "Turn It Over" is a slickly swinging R&B number featuring strong guitar and piano solos. One member of the group takes a solo turn at "Rash Trash," a number in the mold of "You Rascal You," but less creative. The company left these items in the can. "In a Little Spanish Town" is an instrumental feature for Sonny Thompson and the Sharps and Flats; the guitar-piano unison in the theme statement is on the precious side, but Thompson gets to do his Wilson-Tatum thing (becoming more extravagant on the unissued second take), and Garrett takes a swinging solo. (Maybe Egalnick and Simpkins shared our opinion, because the acetate of the master take carries a notation to fade the piece around 2:45, before the out chorus.) "Dreams" is an instrumental ballad on which Thompson pulls several runs out his bag of tricks, but in the end the tune drags him and Garrett down; it was done in two takes only because the band couldn't decide how to end the first). Nothing from the session ended up being released on Miracle, but "In a Little Spanish Town" eventually came out on the British Esquire label in the early 1950s.

During a session a couple of days later, Thompson and the Sharps and Flats without Eddie Chamblee backed Browley Guy on one plodding old schmaltzy ballad ("Tears Follow My Dreams"). They also recorded an instrumental version of the sentimental pop tune, "Moon Is on My Side," in a style akin to King Cole's (and in a better performance than "Dreams" from the previous session). This pairing was promptly released on Miracle 124. Obviously Thompson and the Sharps and Flats could handle material like "Moon Is on My Side," and Thompson was probably doing so regularly during his nightclub sets, but once the bluesy stuff caught on with record buyers, Miracle stopped asking for such performances. Among the instrumental sides from the session, "Blues on Rhumba" and "Just Boogie" (which were used on Miracle 131 and 127, respectively) were better suited to Miracle's intended market. And the laid-back blues "Sonny's Return" was the second item to see release from the session, on Miracle 128. The session stands out among Miracle's from December 1947, because five out of the six sides recorded were released. Just "Swing Alley," a superior performance in a genre that Miracle felt it had no buyers for, was held back.

Sonny Thompson and the Sharps and Flats' final session of the year, which may well have taken place on December 31, brought Gladys Palmer back to redo "Once You Were Mine." Just one take was needed to get a satisfactory result, but the company sat on the song. Palmer completed four others on the date, which would be her last for Miracle. Floyd Hunt was again added on vibes; he can be heard on the first take of the moody ballad "Caress Me," with the motor on his instrument turned up. The other two takes were done without Hunt. "I'll Say It Again" is a run-of-the-mill ballad, lent some interest by Sonny Thompson's piano intro à la Wilson and his Tatumesque runs behind the vocal; "My Heart Cries" is a somewhat better ballad, again with good accompaniment by Thompson et al. With some studio time left over, the late-1920s classic, "If I Could Be with You One Hour Tonight," was given a loose, impromptu performance; unusually for her, Palmer gets into an Ella Fitzgerald groove. "Not on a Xmas Tree" is an impromptu New Orleans-flavored blues featuring Sonny Thompson himself (thanks to Dani Gugolz and Big Joe Louis for verifying this, because Miracle never credited Thompson's vocals on the label). Because Miracle lost interest in Gladys Palmer, only "Not on a Xmas Tree" would see release—and it had to wait for nearly two years.

Egalnick's investment in Sonny Thompson paid off hansomely when Miracle 126, a two-part release of "Long Gone," sold some 200,000 copies and went to the top of the charts. It lasted more than 30 weeks on the Billboard R&B charts, and was still logging non-trivial sales into the first half of 1949. On July 3, 1948, Cash Box announced that "Sonny Thompson and Memphis Slim, setting the pace on Miracle Records, [are] planning a joint nationwide tour in the next few weeks." "Long Gone" even nosed briefly into the pop charts (where it hit #29 for the week of July 10, 1948). The record was so popular that Egalnick had to fight bootleggers in Saint Louis, who were selling counterfeit copies of the record.

Thompson was born Alphonso Thompson in Memphis on August 22, 1916. While he was a preschooler, his family moved to Chicago. He attended Wendell Phillips High School, and studied at the Chicago Conservatory of Music. In the clubs he learned his craft from Art Tatum and Earl Hines. He began working regularly in 1940. After a short time in the Army (he was given a medical discharge after being injured in a cave-in accident), Thompson returned to Chicago to recuperate, resuming work in the clubs as a soloist in early 1944. He continued to work as a solo pianist, except for a period of 7 months (May through December 1945) when he led a big band at El Grotto, the basement club in the Pershing Hotel.

Thompson made his first two sides under his own name as a solo pianist for the Detroit-based Sultan label in May of 1946. Morton Sultan, who owned the label, was a pianist who had studied in Chicago himself; he was no longer performing in public himself but probably admired Thompson's playing. Sultan's gimmick was "double-headed hits," which meant that Thompson, billed for the occasion as the "Prince of the Ivories," split one 78 with an Eddie Wiggins combo and another with Red Saunders. The gimmick wasn't successful, and Sultan quit recording jazz after its first 3 releases, with material from a fourth session never issued. After several months in the Dick Davis combo, which included recording twice for Miracle with them, Sonny Thompson went back out on his own (on August 21, 1947, he posted an indefinite contract to play solo piano at the Bar o' Music). Thompson reached the peak of his performing career with his Miracle sides. After Miracle folded, he recorded extensively for King Records, then handled A&R for the label until 1964, when King closed its Chicago office. Thereafter he produced recordings on an occasional basis for Chess and other labels. Thompson died on August 11, 1989.

A new artist inked by Miracle in 1947 was blues shouter Piney Brown. The singer was born was born Columbus Perry on January 20, 1922, in Birmingham, Alabama. (He has kept his birth name under wraps; we got this information from Brian Baumgartner.) Piney Brown's first music experience was in a family gospel group. In 1940 he moved to Baltimore and there broke into show business. His October 1947 session for Miracle was his recording debut.

Although Piney Brown was described in the February 7, 1948 Chicago Defender as a "Miracle recording artist," just one side was ever released: "That's Right Little Girl," which came out only in Great Britain, on an Esquire release during the early 1950s. We know now that Piney Brown recorded 4 sides with Sonny Thompson and the Sharps and Flats, plus significant contributions by Eddie Chamblee. "That's Right" and "Return of Piney Brown" are declamatory blues showing a strong Kansas City influence; "Return of Piney Brown" even refers to 18th and Vine. "A New Kind of Lovin'" is closer vocally to Wynonie Harris; the number features strong solos by Chamblee, guitarist Arvid Garrett, and Thompson. "Vi," on the other hand, celebrates "a little girl in Chicago."

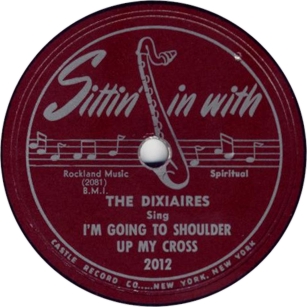

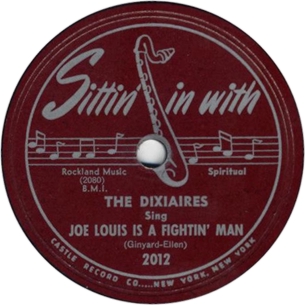

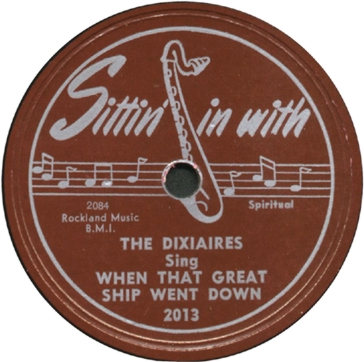

The Defender item said that Piney Brown was beginning a tour on March 13, and added, "The idea is to keep Brown before his record public and put a shot in the arm to a fast dying show business. Plan is to make [a] small compact package and offer to promoters at [a] price enabling them to make a profit. Package will feature Piney Brown, and include Randy Sherman Orchestra, Gip Roberts, comic; Toni Palmer, song thrush; Fred and Sledge, dancers; and Ann Butler, novelty dancer." The rest of the lineup indicates that Miracle wasn't sponsoring the tour. Piney Brown moved on pretty quickly after Miracle failed to use his material; he made a series of recordings in New York City for different labels, starting with Apollo in 1949, then Jubilee (1951), Sittin' in With (1952), Par (1952), and Atlas (1954). After a successful run at the Club DeLisa in a duo with Billy Brooks, Brooks and Brown recorded in Chicago for Duke in 1957 (see the King Kolax discography). In 1959 Piney Brown recorded for Tommy Jones' Mad label. Brown subsequently moved to Kansas City, and then to Dayton, Ohio, recording for several other small companies.

See the outstanding article by Brian Baumgartner, "Piney Brown: Now and Then," Juke Blues No. 48 (2000), pp. 28-37.

1947 was the make-or-break year for Miracle. Egalnick and Simpkins invested in 100 recorded sides that year, most of them during the frantic last quarter. Some of these items (the Memphis Slim numbers, and the Sonny Thompson R&B instrumentals) would keep bringing in revenue as long as the company was still in operation. Too many others lost their salability before 1948 was out, if they had any to begin with.

| Matrix | Artist | Title | Release # | Recording date | Release date |

| UB21046 [M-536] |

Dick Davis Orchestra featuring Sonny Thompson | Memphis Train | Miracle 109 | c. 1/47 | 6/1948? |