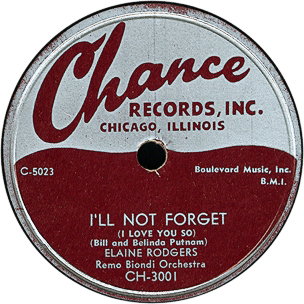

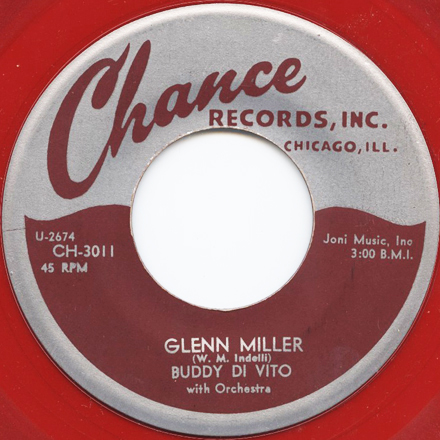

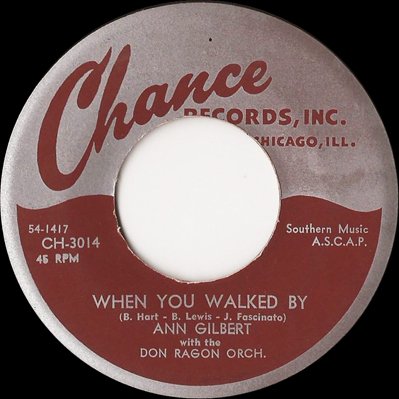

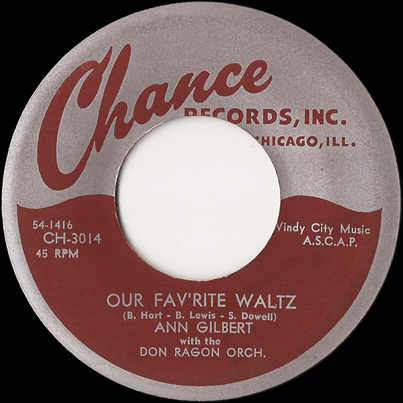

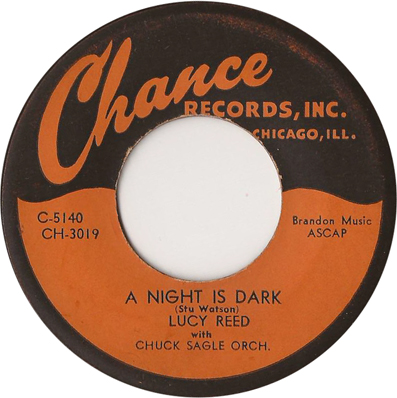

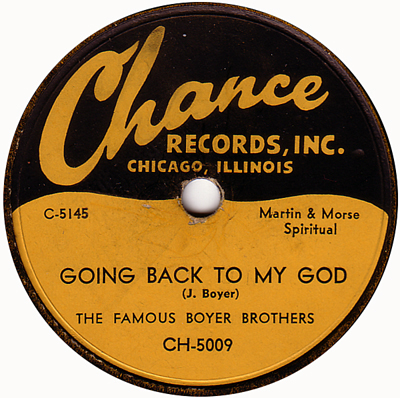

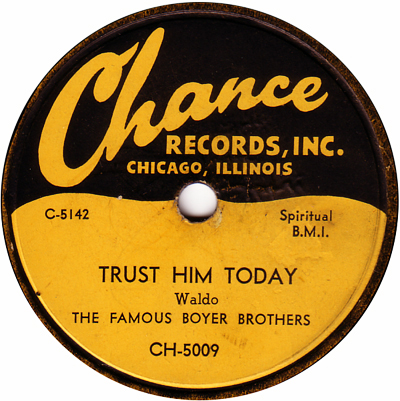

Revision note: We've provided more accurate background on Kitty Stevenson, whose Vitacoustic sides were acquired by Art Sheridan in 1952 (but not released on Chance). We've updated our listing for "Everything I Have Is Yours" by the Four Shades of Rhythm, which we can now also identify as a track originally recorded for Vitacoustic (even though we know only a Sensation matrix number for it). We have added some information about Art Hoyle, who worked with Schoolboy Porter, and about Don Ragon, whose band appeared on one Chance pop release. Courtesy of Big Joe Louis, we have a little more information about Chance 5001 by the Southern Clouds and Chance 5009 by the Boyer Brothers. We have added some material on Buddy DiVito, whose "Take My Heart" (released for a hot minute in 1951, on Tower 1508), may have been reissued on Chance 3015. DiVito had also made a single for Sharp in 1952, during that label's decline phase. We are able to say a tiny bit more about Henry Green, who was definitely a gospel performer. We are still upgrading our biographies of Lucy Reed (Chance 3006 and 3019) and Elaine Rodgers (Chance 3001). There are a few Chance releases we need to know more about, such as Chance 1100 by Arnold Jones, and Chance 5004 and 5005 in the gospel series. In the 3000 pop series, we'd still like to know for sure whether the Four Bits (Chance 3003) were the comedic quartet from South Florida... We'd also like to know who Jack Nelson was (Chance 3004; he later recorded for Stepheny), but we've come a long way.

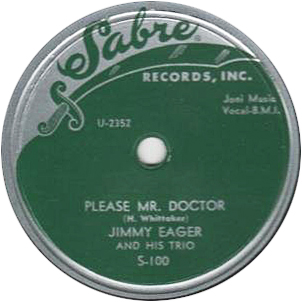

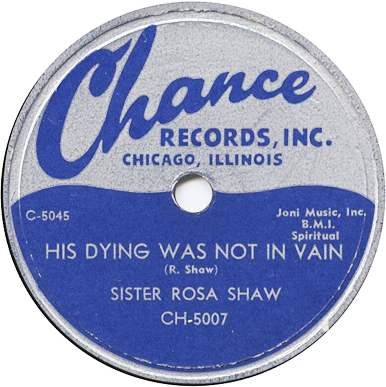

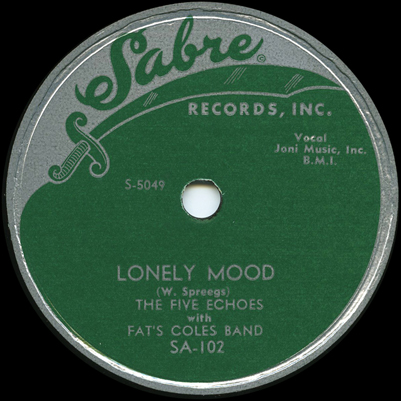

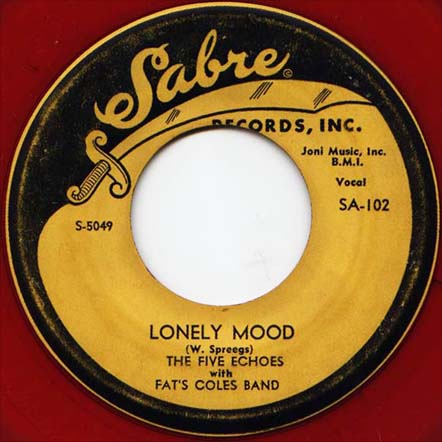

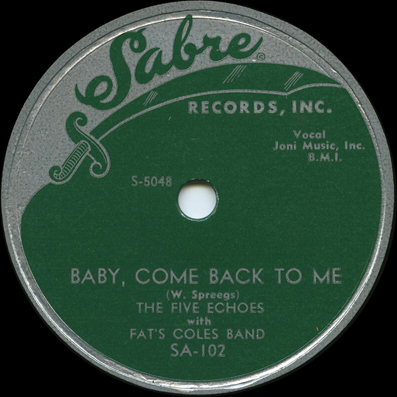

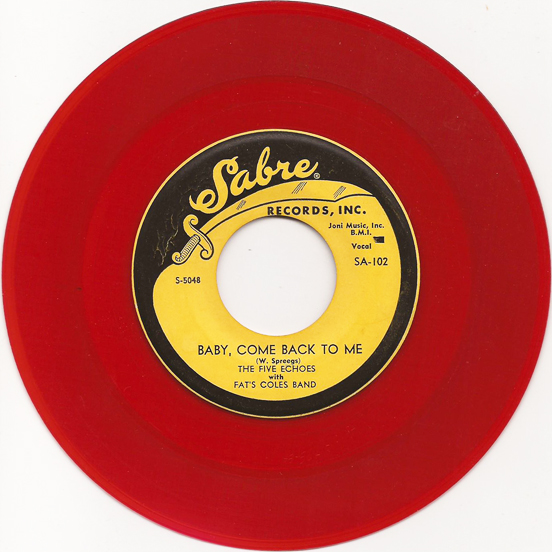

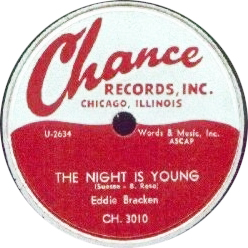

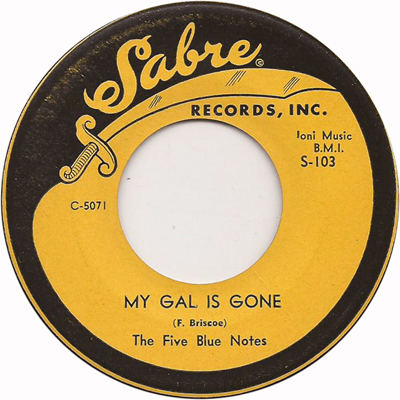

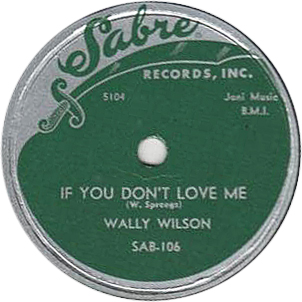

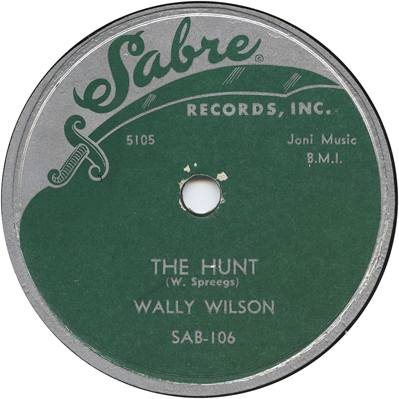

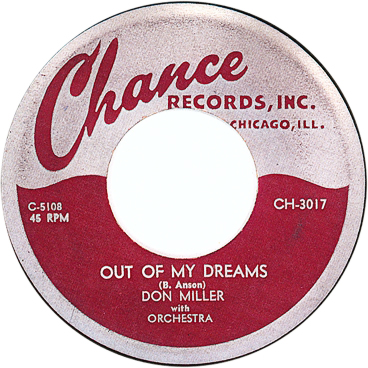

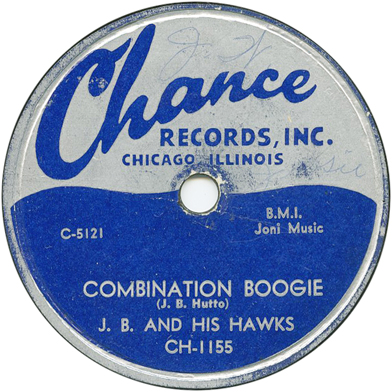

Chance Records, like Parrot, United, and Aristocrat, was an independent Chicago label that pioneered in recording the new African-American sounds that swept the city after World War II: the electrified Mississippi blues and the doowop harmony groups. Chance cut 360 known sides from September 1950 through October 1954. In addition, Chance purchased or licensed at least 44 sides. We know of 94 releases on Chance, accompanied by 1 on its very short-lived tributary Meteor and 9 on its later subsidiary Sabre.

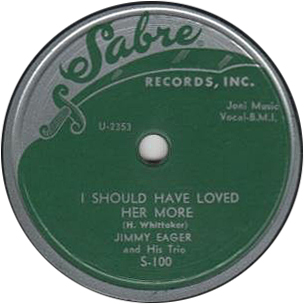

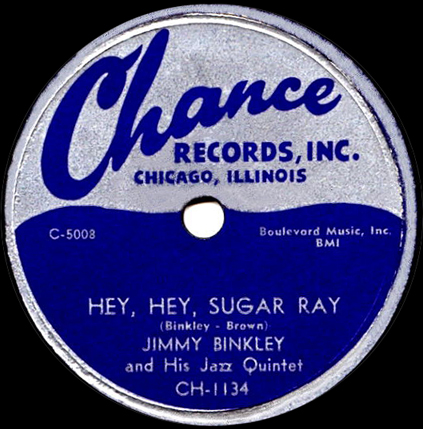

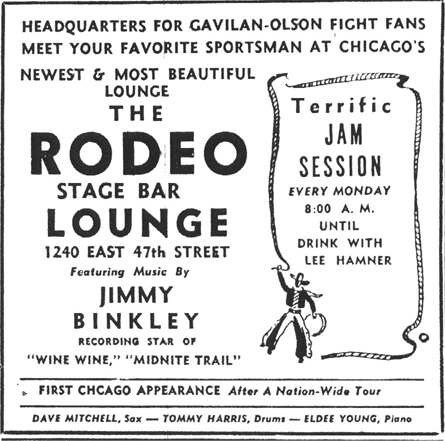

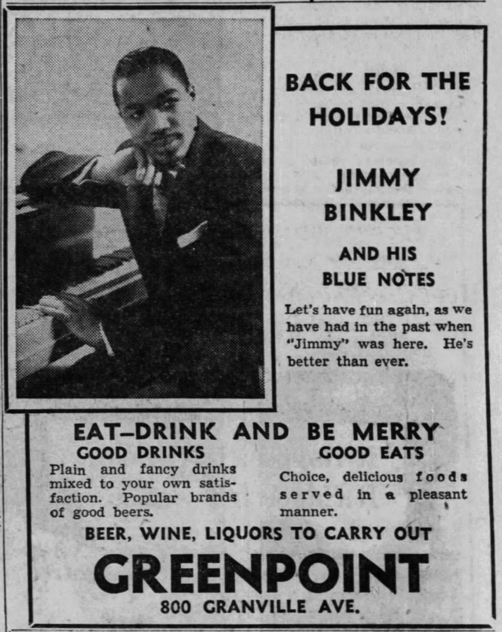

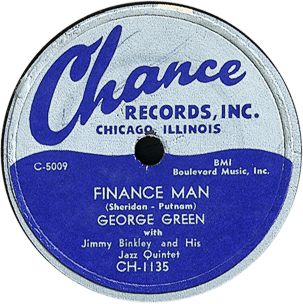

Although the blues and doowop garnered Chance a place in history, the company recorded pop, jazz, and gospel, and this discography is designed to profile those aspects of the label as well. The jazz sides were by the Wally Hayes Combo aka Calumet City Boys aka The Chanceteers, John "Schoolboy" Porter, the Jimmy Binkley Jazz Quintet, Chubby Jackson, Conte Candoli, Johnny Miller, and Remo Biondi. Schoolboy Porter recently got a limited-edition 10-inch LP from Japan; otherwise, just two of the jazz sides have been reissued.

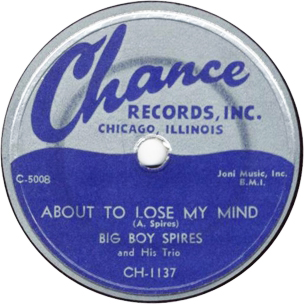

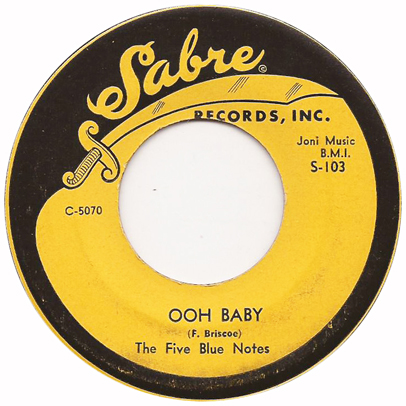

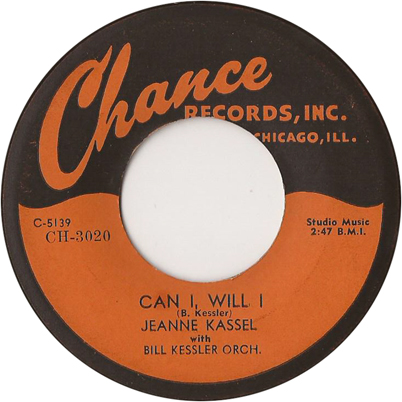

The bulk of Chance's output was in the R&B field, which reflected the knowledge amassed by the label's founder and owner, Art Sheridan. Sheridan (born July 16, 1925 in Chicago) had been running a distributor and a pressing plant, where the preponderance of his work was with African-American-oriented product. The main Chance 1100 series, the temporary Meteor 100 series, and the Sabre 100 series concentrated on blues, jazz instrumentals, doowop groups, and solo R&B stylists. The company also ran a Chance 3000 series for pop (with 21 releases) and a Chance 5000 series for gospel (for which we know 10 releases).

Most Chance recordings were done at Universal Recording Corporation (which was the source of the two main Chance master series: one starting in the U1800s and obviously shared with other labels; the other an exclusive series that began at U5000 or C5000, prefix not handled consistently). Some recordings were picked up from other sources and some were recorded at other studios in town. We know, for example, that the first Homesick James Williamson session was recorded at RCA Studios.

Our basic source for this work is a roughly chronological list of matrix numbers, artists, and titles provided by Art Sheridan to the French discographical researcher, Marcel Chauvard (1926-1968). We have thoroughly checked and considerably amplified his listing, but without M. Chauvard's work our discography would not have been possible. As often happens when working from company files, Sheridan sometimes supplied titles that were not used on the labels. When there is a disagreement, Sheridan's title appears in square brackets after the title that ended up being used. Occasionally Sheridan's matrix numbers disagreed with those that appeared on the labels; such numbers are also shown in brackets.

The Chance label officially opened for business in September 1950. Its headquarters were initially in the offices of Sheridan's American Record Distributors, located at 2011 South Michigan Avenue in Chicago. Art Sheridan had started American Record Distributors in December 1949, along with Evelyn Aron, who sold her share in Aristocrat to Leonard and Phil Chess (Cash Box, December 17, 1949, p. 16). Sheridan also operated a pressing plant called Armour Plastics. In March 1950, his pressing operation expanded by absorbing the remnants of Egmont Sonderling's Master Records (see our Old Swing-Master page). In July, Sheridan acquired the plating plant from Sonderling's mastering operation (Billboard, July 8, 1950, p. 19). Sonderling was shifting his holdings out of the record business and into radio stations.

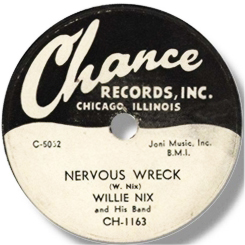

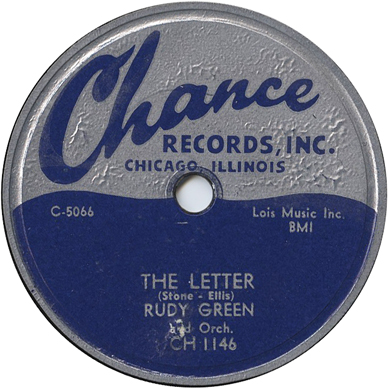

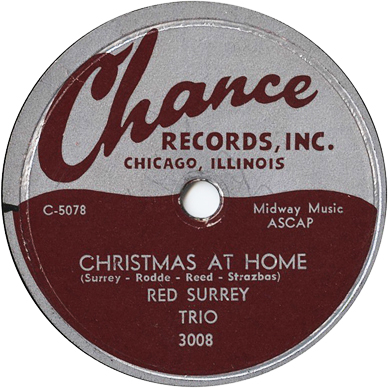

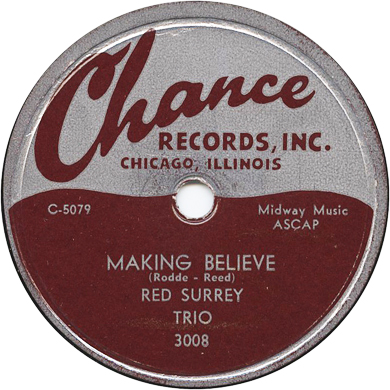

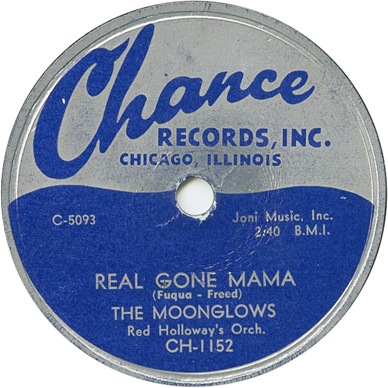

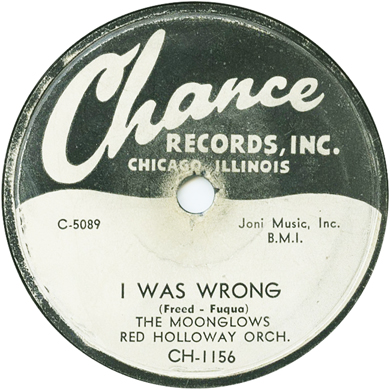

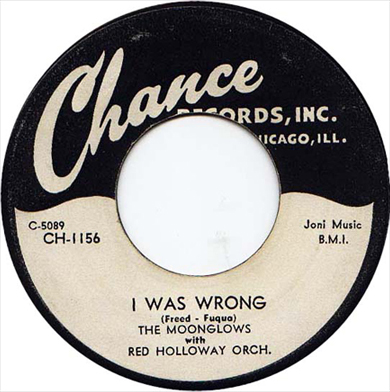

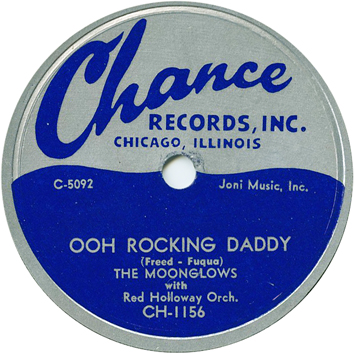

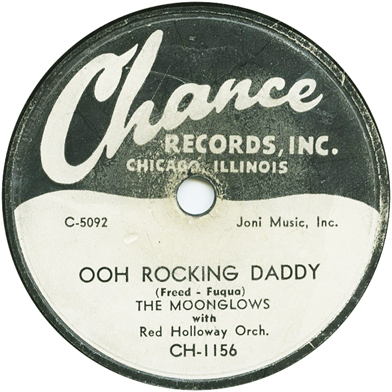

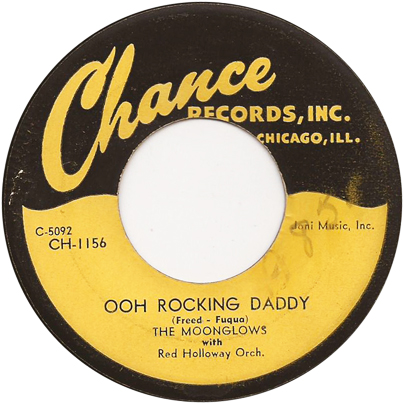

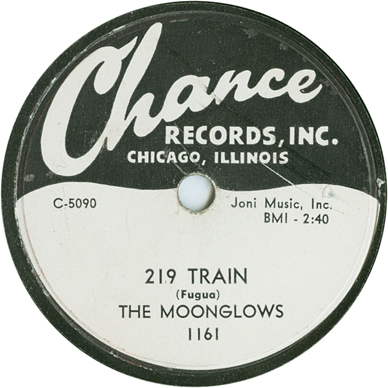

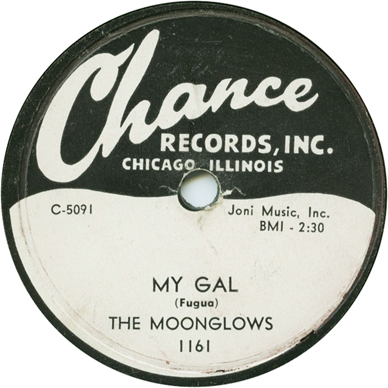

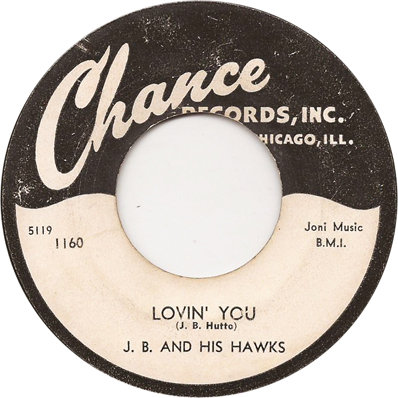

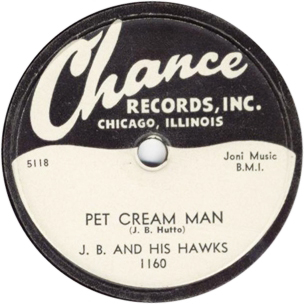

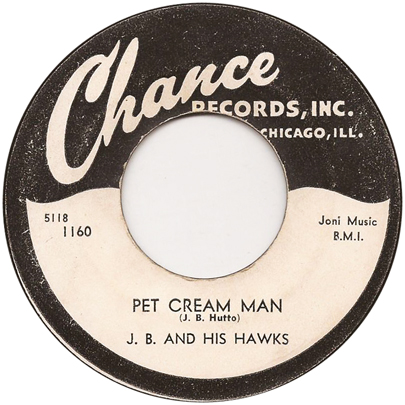

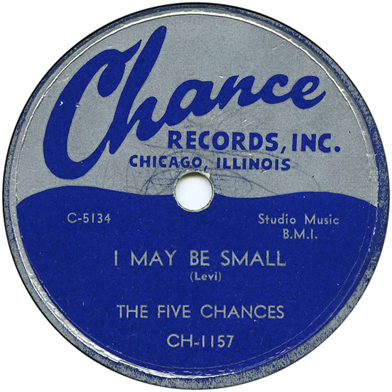

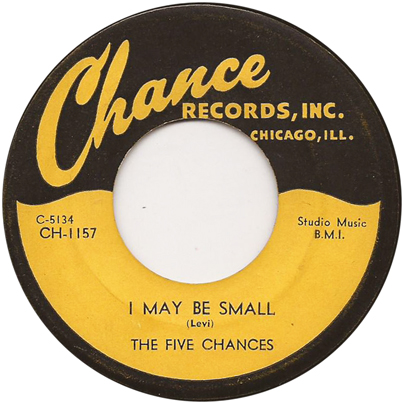

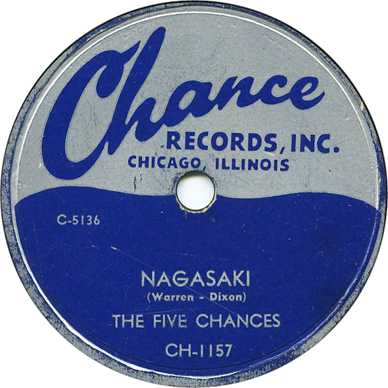

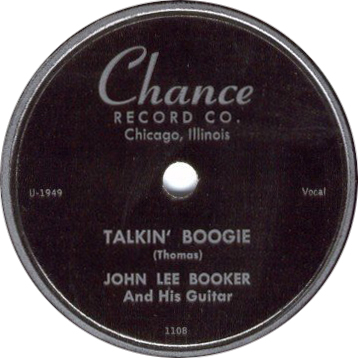

The first Chance label (on 78s) was black, with a silver rim and silver print. This was plain-looking, but serviceable, and Sheridan kept it until November 1952 (through Chance 1121). When Chance 45s eventually hit the market—the company was in no big hurry—they used a plain blue background and silver print. Because Chance made a late move to 45 rpm, nearly all of the company's 45s would appear with later label designs.

The company initially kept an extremely low profile. So low, we're inclined to wonder what was going on. In its first year and a half in business (September 1950 to the beginning of March 1952), Chance Records was mentioned all of four times in Billboard—and once in Cash Box. Art Sheridan had been in the business for a little while by then, and his initial partner in distribution, Evelyn Aron, had gotten a lot of ink out of both trades while she ran Aristocrat.

In any event, on December 16, 1950, Billboard announced that "Steve Chandler, local realty agent, has started Chance label. First r. and b. releases are by John (Schoolboy) Porter, tenor saxman, and his trio" (p. 16). (The very next item, not so coincidentally, was about Patti Page getting hastily re-booked into the Chicago Theater.) This was the only trade magazine notice Chance would get in 1950. It came three months after the company had opened, when it already had four releases out, one of them a cover of Patti Page's new hit. No ads. No records submitted for review. No mention of Art Sheridan. Who was Steve Chandler?

Chance's very first session had featured one Arnold Jones, who to judge from the titles he cut was a ballad singer. We can say no more, as Jones' solitary release on Chance 1100 is amazingly scarce and in 22 years at RSRF we have yet to hear it. Sales were evidently not militating for the release of the other two sides that Jones had recorded.

What really got the label started was its second session, consisting of four instrumentals by tenor saxophonist Schoolboy Porter. John A. Porter was a 24-year old native of Gary, Indiana, who had served for 2 1/2 years in the Navy during World War II. In the summer of 1947 he joined the Cootie Williams Band in Indianapolis and toured the Eastern states. Service with Williams helped him develop into a formidable honker (unfortunately, Porter didn't stay long enough to get onto a recording session, so we can't line his solos up against the work of "Weasel" Parker and "Gator Tail" Jackson). In 1948, he enrolled in the Midwestern College of Music, where he stayed for a year. After gigging around with some other bands in the Midwest, Porter was brought to the label by Gary deejay Jesse Coopwood.

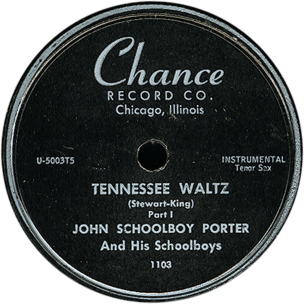

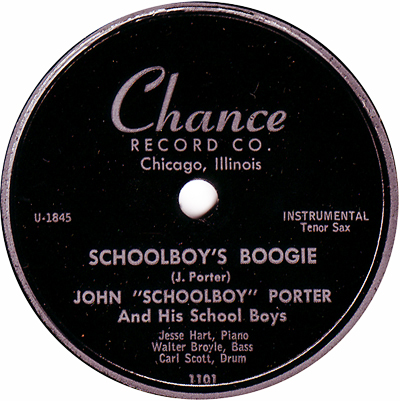

Schoolboy's first Chance release, an instrumental of the Tommy Dorsey / Frank Sinatra song, "I'll Never Smile Again," was something of a local hit in the fall of 1950. It was backed with "Schoolboy's Boogie," a number not in need of further explanation. Porter was backed by a rhythm section, consisting of Jesse Hart's rather florid piano, Walter Broyle's bass, and Carl Scott's drums. Studio reverb was laid on during his solos—more heavily on the ballads, as was the custom at the time. "Kayron" was a driving bop number on which Schoolboy showed off his jazz chops; "Deep Purple" was an affecting ballad performance.

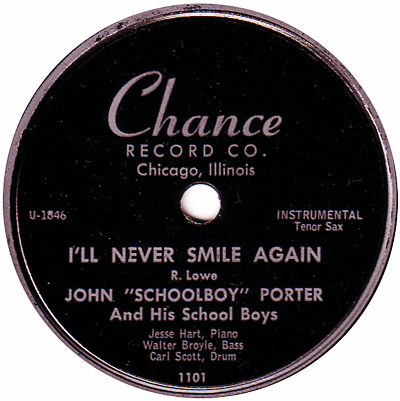

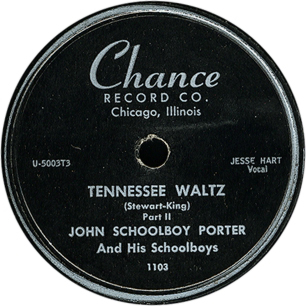

On November 15, Chance brought the same combo back to whip out a two-sided release of "Tennessee Waltz." Periodically a song would send the entire recording industry into a gold rush; "Tennessee Waltz" was the latest. The song has already been a Country and Western hit for Pee Wee King, who wrote the music to it, recorded it for RCA Victor in December 1947, and got it release in January 1948; then for Cowboy Copas, whose single on King was released in March 1948. More than 2 years later Erskine Hawkins' band, with Ace Harris singing the lyrics, cut an R&B version (Coral 60313 was listed as a new release in Billboard on October 14, 1950, p. 44). In turn, pop singer Patti Page, then in her third year with Mercury, was in the studio in mid-October to make a rush version of Mabel Scott's "Boogie Woogie Santa Claus" for the Christmas trade. Needing a B side even quicker, Page's manager and Mercury's East Coast A&R man noticed the Erskine Hawkins release. Mercury 5534 was rocketed into release at the beginning of November, becoming a monster hit on the strength of its B side. Mercury's advertising campaign was so hasty that the first display ad for the single give the wrong catalogue number. Patti Page's "Waltz" was #1 in the charts well past the New Year, selling well over a million copies. In January 1951, the no longer seasonal "Boogie Woogie Santa Claus" had to be replaced. On subsequent pressings of Mercury 5534, the B side was a brand-new recording of "Long Long Ago."

Lots more renditions of "Tennessee Waltz" would given priority recording, mastering, pressing, and distribution over the next few weeks. Some of the cover singles sold in the hundreds of thousands. Without a network that extended beyond American Record Distributors, Chance would have to be content with local sales. Still, Porter's "Tennessee Waltz" sold some 10,000 copies; Armour Plastics couldn't press that many in time, so part of the work was entrusted to RCA Victor's custom pressing operation in Chicago (such copies bear an extra matrix number on each side in RCA's E0 series). Said Sheridan, "That was the era when the saxophone solos and the saxophone copies of popular tunes were very popular. Patti Page had a big hit with 'Tennessee Waltz,' and it was just a normal thing to put out an instrumental on a pop hit as soon as you heard one that seemed to be going somewhere." Sheridan hedged his bet by including a square vocal by Schoolboy's pianist Jesse Hart on the B side.

Claude McLin, who'd scored a hit for Chess in August-September 1950 with his sax solo version of "Mona Lisa," also cut "Tennessee Waltz." But even though Chess had a lot better distribution than Chance at this stage in the game, Porter's version trounced McLin's at the cash register.

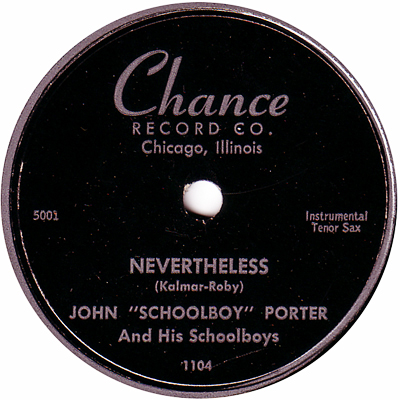

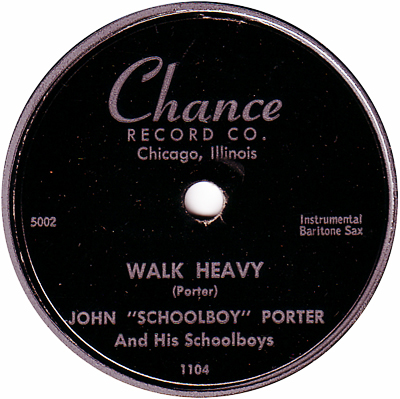

Three more sides were cut at the session. "Nevertheless" is a well-done ballad, and "Walk Heavy" got its name because Schoolboy played baritone sax on it; judging from this outing on the big horn, he could have given Leo Parker a run for his money. In all, Porter would be responsible for 4 of the 6 initial releases on the label: Chance 1101, 1103, 1104, and 1105.

Between the first and second Schoolboy Porter sessions, the company recorded two sides on the Al Sims Trio. Released on Chance 1102, both were uptown blues featuring an excellent vocalist named Sam Dawson. "I Wonder, Baby," a proto-rock-and-roll number, also features a two-chorus guitar solo. Sam Dawson was a guitarist, and presumably did the honors himself; did he leave any other recordings behind? "Moody Woman" is in the Charles Brown vein. Good as the results sound to us today, the sales must have been disappointing, because Sheridan (or was that Chandler?) didn't call Sims and company back.

The remainder of the label's early recording activity consisted of a coupld of big sessions featuring singer Clyde Wright and a jazz group (usually a quintet) led by Wally Hayes. Sheridan (or was that "Chandler"?) referred to the group by several names. On Chance 1106 and the first pressing of Chance 1107, the group was credited as the Wally Hayes Combo. (Our thanks to Richard Reicheg for alerting us to the Hayes variant of 1107.) Chance 1106 by Clyde Wright and the Wally Hayes Combo eluded discographical attention for 60 years; obviously it was pressed just once. On Meteor 100, a release nearly as rare, the group became the Calumet City Boys. Marcel Chauvard took down a "Copwood Session," a reference to the Gary deejay, Jesse Coopwood, who may have produced it. Going by the titles (because several of the items have never been released), we think the "Coopwood" items were mostly instrumentals by one of Wally Hayes' groups.

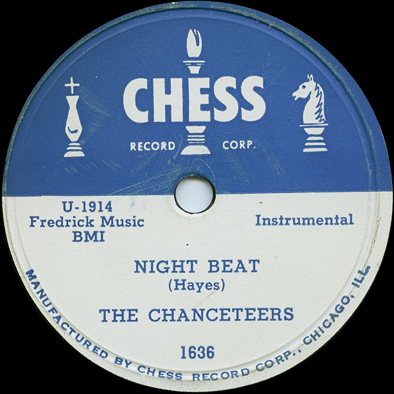

In April 1952, as the Chance label was being resurrected, Chance 1107 reappeared, first on 78 rpm (where it is much more common than the first pressing) and after a while on 45. The same titles, with "Hayes" still given as the composer on both sides, were now credited to "The Chanceteers." Publicity during the next three months claimed a major spot on the company's talent roster for The Chanceteers. But only the retreaded Chance 1107 and one side of Chance 1112 (released in March 1952, after already appearing on Meteor 100) were the only ones to use the name for the Wally Hayes Combo. To maximize confusion (and differentiate the records from those that been made with non-Union musicians), Schoolboy Porter's June 1951 group was called the Chanceteers on Chance 1111, probably released in October 1951, and on the side of Chance 1112 on which the group accompanied Clyde Wright.

We wish we could say more about the Wally Hayes Combo, a solid group that may also have included some who weren't paid up with the Union. Wallace Hayes was a drummer who had been active in the South Side clubs since 1945 or 1946, and would continue on the Musicians Union Local 208 contract lists through 1955. In 1946, he had William Huddleston (the future Yusef Lateef) playing tenor saxophone in his group, but there is a sore lack of information about the other musicians who worked with him. The combo he led for these studio dates included an excellent alto saxophonist, who is prominent on both sides of Chance 1106, 1107, and one side of 1112, along with piano, guitar, and bass. It would be nice to be able to name them, but the trail is stone cold. On one issued side (maybe too on some still unissued), trumpet and tenor sax were added.

Why it was singled out for such an honor we don't know, but Chance 1107 was reissued in 1956 as Chess 1636, under the Chanceteers name. We have no evidence of further Chance material being picked up by the Chess brothers—in this transaction or in any other.

The matrix number on "I'm Nobody's Trick," a blues sung by Clyde Wright, brings up more questions. Sheridan wrote down 2016, which was the number on Meteor 100. But Chance 1112, the March 1952 release that coupled the number with a side on which Wright sang with Schoolboy Porter's band in July 1951, shows U2105 on the label. (It's still 2016 in the trailoff...) Chance 1112 was one of the first products of Sheridan's revival, garnering a review in Cash Box on March 22, 1952 (p. 22).

Yet on "Trick" Wright is obviously backed by the same band that can be heard on Chance 1106 and 1107, and we've listed the side with the other Wally Hayes items. We suspect the "Nobody's Trick" matrix number was purposely altered for Chance 1112. If the renumbering helped to erase the recording trail, so much the better...

Meteor 100 is a 78 that was rediscovered by Bob Buchholz. It has a silver on blue Meteor label. There is no connection with the silver on red Meteor label operated by Lester Bihari (which, just to confuse matters, would license some Al Smith sides from Chance in 1953). This Meteor label is laid out just like an early Chance label (silver rim, same type face in the logo) except it's blue instead of black. "I'm Nobody's Trick" carries 2016. The other side, "Club 21," carries matrix 2017 and was never issued on Chance. Both sides of the Meteor are credited to the Calumet City Boys (abbreviated as "Cal City Boys" in the list Sheridan gave to Chauvard). Neither Meteor 100 nor Chance 1112 has composer credits at all.

"Club 21" throws in a reference to State Street but the main function of this Swing number is to talk up the strip joints of … Calumet City. A couple of further oddities: the vocalist is not Clyde Wright, and the alto saxophonist is joined up front by an excellent trumpet player with bop tendencies and a tenorist out of the Lester Young school. We wonder who the tenor player was, as the possibilities were fairly finite on the Chicago scene at the time. The horns and the bass all get to solo.

The much better known Lester Bihari Meteor label out of Memphis (which would be carried by Sheridan Distributors in Chicago) was launched in November 1952, and its first releases were advertised in the trades in December. By then Sheridan had long since decided to drop his own Meteor logo, after one release. The release date on Meteor 100 remains uncertain but obviously it was before Chance 1112 came out. Our best guess is the second half of 1951.

Chance was just starting: the company's total output for 1950 was 25 tracks. For whatever reason, the company was said to be Steve Chandler's, not Art Sheridan's, and coverage in the trades was limited to one delayed announcement, in Billboard, that the company had opened.

| Matrix | Artist | Title | Release Number | Recording Date | Release Date |

| *U1823 | Arnold Jones | Some Time | Chance 1100 | prob. August 1950 | prob. September 1950 |

| *U1823 [sic] | Arnold Jones | Wilderness | unissued | prob. August 1950 | |

| *U1824 | Arnold Jones | Yesterdays | Chance 1100 | prob. August 1950 | prob. September 1950 |

| *U1824 [sic] | Arnold Jones | Dark Eyes | unissued | prob. August 1950 | |

| *U-1845 | John "Schoolboy" Porter and His School Boys | Jesse Hart, Piano | Walter Broyle, Bass | Carl Scott, Drums | Schoolboy's Boogie | Chance 1101 | prob. September 1950 | September 1950 |

| *U-1846 | John "Schoolboy" Porter and His School Boys | Jesse Hart, Piano | Walter Broyle, Bass | Carl Scott, Drums | I'll Never Smile Again | Chance 1101 | prob. September 1950 | September 1950 |

| *U-1853 | John "Schoolboy" Porter and His Schoolboys [some copies: John Porter, His Tenor Sax and His Orchestra] |

Kayron | Chance 1105 | prob. September 1950 | March 1951? |

| *U-1854 | John "Schoolboy" Porter and His Schoolboys [some copies: John Porter, His Tenor Sax and His Orchestra] |

Deep Purple | Chance 1105 | prob. September 1950 | March 1951? |

| *U-1861 | Al Sims Trio | Sam Dawson Vocal | Moody Woman | Chance 1102 | October 1950 | late 1950 |

| *U-1862 | Al Sims Trio | Sam Dawson Vocal | I Wonder, Baby | Chance 1102 | October 1950 | late 1950 |

| *U5000 | John Porter | High Tide | unissued | November 15, 1950 | |

| *5001 | John "Schoolboy" Porter and His Schoolboys | Nevertheless | Chance 1104 | November 15, 1950 | December 1950 |

| *5002 | John "Schoolboy" Porter and His Schoolboys | Walk Heavy [Wig Deal] |

Chance 1104 | November 15, 1950 | December 1950 |

| U1855 *U5003T3 (T5 on label) E0-0B-13019-1 A A (in wax on some copies) |

John Schoolboy Porter and His Schoolboys | Tennessee Waltz Part I | Chance 1103 | November 15, 1950 | November 1950 |

| U1856 *U5003T5 (T3 on label) E0-0B-13020-1 A (in wax on some copies) |

John Schoolboy Porter and His Schoolboys (Jesse Hart Vocal) | Tennessee Waltz Part II | Chance 1103 | November 15, 1950 | November 1950 |

| U-1910 [*No Number] |

Clyde Wright with the Wally Hayes Combo | Whispering Grass [Green Grass] |

Chance 1106 | December 1950 | Early 1951 |

| U-1911 [*No Number] |

Clyde Wright with the Wally Hayes Combo | Hear My Call [No It Wasn't Right] |

Chance 1106 | December 1950 | Early 1951 |

| *U1913 | Wally Hayes Combo The Chanceteers |

The Flame [The Heat] |

Chance 1107 | December 1950 | Early 1951 April 1952 |

| *U1914 | Wally Hayes Combo The Chanceteers |

Night Beat | Chance 1107 | December 1950 | Early 1951 April 1952 |

| *No Number | [Jesse] Coopwood Session | Man of Parting | unissued | Dec. 1950 | |

| *No Number | Coopwood Session | Red Sails in the Sunset | unissued | Dec. 1950 | |

| *No Number | Coopwood Session | The City... | unissued | Dec. 1950 | |

| *U2016 U2105 on label |

Calumet City Boys Clyde Wright and The Chanceteers |

I'm Nobody's Trick | Meteor 100 Chance 1112 |

c. December 1950 | 1951? March 1952 |

| *U2017 | Calumet City Boys | Club 21 | Meteor 100 | c. December 1950 | 1951? |

Chance sputtered and almost went out in 1951. The company did record some titles during June and July on blues man Henry Green, plus more by Schoolboy Porter and Clyde Wright, but its total studio output came to a meager 11 sides.

After its peculiar, delayed announcement in Billboard, the company held off sending in singles for review until March 1951. Chance 1101, 1103, and 1105 were announced as new releases on March 10, 1951 (pp. 26-27). Except for Chance 1105, where we have no confirmation of an earlier date, these were obviously not new releases, and Billboard didn't review them. What followed in Billboard wasn't exactly favorable.

The company got into serious trouble in May, when the American Federation of Musicians, at the behest of its Chicago Local 208, revoked Chance's recording license for using non-union musicians on Schoolboy Porter's first session, the one that produced "I'll Never Smile Again." No union contracts for these sides were ever turned in to the AFM office. Billboard ("Petrillo Nixes Art Sheridan's Disking License," May 19, 1951, p. 13; the story was dated May 12) related that Sheridan "had okayed the use of his franchise by Steve Chandler, who cut the disks and had them pressed by Sheridan's Armour Plastics pressery." According to Sheridan "Chandler claimed that he used boys who had union cards, but who, at the time of the sessions, were not paid up members. As a result, he held back the contracts and the union took action."

The magazine reported that the revocation of the license was the "first such action locally in a long time." This we have no trouble believing. Some of the other record companies we have covered at RSRF were called in front of Local 208: Chess for recording in the back room at 4750 South Cottage Grove, Parrot/Blue Lake for recording two-tune sessions, United for using one musician on a session who wasn't current with his Union local. None of the others was ever hit with such sanctions.

When Robert Pruter talked to him in 1992, Sheridan amazingly said he had no recollection of a person named Steve Chandler or recalled any AFM problems. Said he, "It could have happened, but I don't recall having a difficult time with the AFM." Sheridan has said about operating the company, from management to producing, "I did it all in the beginning." Billboard, which mentioned Chandler in December 1950 and again on this occasion, gave no indication of actually talking to him—perhaps because he didn't exist. Besides which, Sheridan had taken out the recording license for Chance. Why would he start a new record company to turn over to another operator?

What if Art Sheridan realized in December 1950, by which time Schoolboy Porter had made two sessions with cats who weren't straight with the Union, that the local sales on Chance 1103 were making his company visible enough to invite attention from a Union local? Hence the delayed announcement using someone else's name? The complaint and the investigation took a while. In the May 19, 1951 article, Sheridan claimed he'd heard nothing till late April, which was when the AFM caught up with him (one wonders how many letters had been addressed to Steve Chandler).

For that matter, we doubt Henry Green was a member of the Union when Sheridan recorded him on June 5, 1951. Judging from what he cut for Chance, he was considered a gospel performer. He could have avoided joining. Only two of Green's sides were released, on Chance 1109, another rare entity today. "Strange Things" sees portents of the apocalypse; "Storm through Mississippi" is about divine wrath being visited on the "mighty, mighty sinful town" of Tupelo. Accompanied only by his electric guitar, Green was roughly halfway stylistically between Blind Willie Johnson and Pops Staples, though not as intense a performer as either. Chance 1109 has gotten decent coverage on YouTube, where a comment from 2014 indicates that he was then living in Illinois, at the age of 99 (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NSNcUKgk6Zg). It would be nice to know more.

Although the Billboard story made the revocation appear immediate, time was left to get in another Schoolboy Porter session. Porter had been on the road; in April he was working the Ebony Room in Cleveland, in Les Fisher's All Stars. Fisher, a drummer, had put together a quintet with Schoolboy and an alto saxophonist in the front line, plus piano and bass and two vocalists, Aretta LaMarr and "Curley" McClau ("'Cinderella' Band Takes over Cleveland by Storm," Cleveland Call and Post, April 28, 1951, p. 18; the singers got most of the ink, but "Schoolboy Boogie" did rate a mention.)

The studio band for the July 1951 session at Universal consisted of trumpet, baritone sax, piano, bass, and drums. Porter's non-Union rhythm section was not invited back. The label of Chance 1111 provides the names of the new band members.

Art Hoyle (who was also from Gary, Indiana) played trumpet. Arthur Hoyle was born in rural Oklahoma in 1930. He got his first trumpet as a present for his eighth birthday. He moved to Gary with his mother in 1943 and began playing locally when he was 15. He spent 4 years in the Air Force, where met John Gilmore (Gilmore served from 1948 to 1951). An ardent bebopper, Hoyle went on to work in Sun Ra's Arkestra (1955-1956). Hoyle left the Arkestra to tour with Lionel Hampton, spent some time with Lloyd Price, then returned to the Chicago area. For many years, he was active as a musician, appearing on many recording sessions in the 1960s and 1970s. He also did voiceovers for commercials. Art Hoyle died on June 4, 2020, at the age of 90 (see https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/post-tribune/obituary.aspx?n=arthur-hoyle&pid=196306766).

Floyd Dungy, an Indiana native, subsequently played bass on two early sessions for Vee-Jay, with blues singer Pro McClam in September 1953, and with McClam and trumpeter/singer Floyd Valentine in June 1954.

The pianist, Eugene McDuffy, was originally from downstate Illinois. He would be much better known—after he changed his name to Jack McDuff and took up the Hammond B3 organ.

Mr. McDuffy gets nice piano solo on the hard bop blues "Rollin' Along" and a briefer outing on the low-down slow blues "Soft Shoulders," but otherwise the sides are Schoolboy all the way. Singer Clyde Wright, on his second and last session for the label, does his Andrew Tibbs impression on "I May Be Down," which features spirited riffing and a heated solo by the leader.

The session data for 1951 confirm that the label didn't record again for 5 or 6 months, and didn't use Union musicians again for 8 months. Apparently the revocation went into effect toward the end of July. Art Sheridan, his phantom frontman "Chandler," and Chance Records would remain on the Union's "unfair practices" list for the rest of the company's history. Sheridan kept his status of persona non grata with Musicians Union Local 208 long after Chance had closed its doors.

Knowing that Chance wouldn't be back until the fall, maybe wouldn't be back at all, Schoolboy Porter joined Lionel Hampton's big band for a spell. In the fall of 1951 he replaced R&B honker Morris Lane, who had gone off to form his own band. This must have been on an emergency basis; according to a 1958 item in the Chicago Defender, Porter had to learn the band's entire book on short notice, with few opportunities for rehearsal.

| Matrix | Artist | Title | Release Number | Recording Date | Release Date |

| *U-1951 | Henry Green | Storm thru Mississippi [Storm thru Tupelo] |

Chance 1109 | June 5, 1951 | 1951 |

| *U-1952 | Henry Green | Strange Things [Strange Things Happening] |

Chance 1109 | June 5, 1951 | 1951 |

| *U1953 | Henry Green | Jesus Is Going to Make Up | unissued | June 5, 1951 | |

| *U1954 | Henry Green | No Need to Run | unissued | June 5, 1951 | |

| *U1965 | Schoolboy Porter and his School Boys | Soft Shoulders [School's Blues] |

Chance 1114 | July 25, 1951 | April 1952 |

| *U1966 | Schoolboy Porter and his School Boys | Rollin' Along [Tojo's Boogie] |

Chance 1114 | July 25, 1951 | April 1952 |

| *U-1966B | Schoolboy Porter and the Chanceteers | J. Porter, tenor sax; Dungy, bass; Vacirco, drums; Hoyle, trumpet; McDuffy, piano; Peterson, baritone sax | Top Hat [Question Mark] |

Chance 1111 | July 25, 1951 | October 1951 |

| *U1967 | Schoolboy Porter and the Chanceteers | J. Porter, tenor sax; Dungy, bass; Vacirco, drums; Hoyle, trumpet; McDuffy, piano; Peterson, baritone sax | Stairway to the Stars | Chance 1111 | July 25, 1951 | October 1951 |

| *U-1968 | School Boy Porter and his Schoolboys | Sentimental Journey | Chance 1117 | July 25, 1951 | August 1952 |

| *U1969 | Clyde Wright and The Chanceteers | I May Be Down | Chance 1112 | July 25, 1951 | March 1952 |

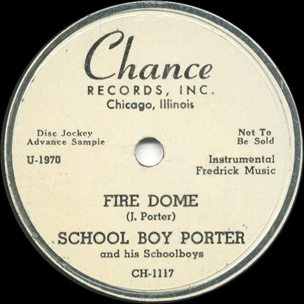

| *U-1970 | School Boy Porter and his Schoolboys | Fire Dome [Land of the Misch.] |

Chance 1117 | July 25, 1951 | August 1952 |

It's unclear to us now, but around January 1952, after several months of no recordings, Chance may have slid temporarily into dormancy. Chance finally started getting serious attention from the trades in late February 1952, but the publicity that followed usually made it look like a new company. Maybe it was a new company, from Art Sheridan's point of view; Chandler's ghost was exorcised at last.

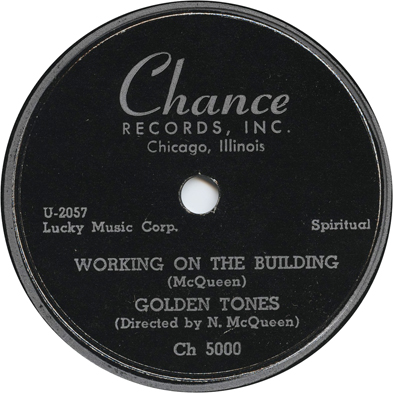

In the first four months of 1952, studio activity concentrated on gospel acts—the Heavenly Wonders, Southern Clouds, Golden Tones, and Naomi Baker—for a new 5000 series. We know little about these performers. There was a pragmatic rationale for the change of genre: a record company did not need permission from the Musicians Union to record gospel singers. Not until 1956 would Local 208 begin cracking down on the non-Union keyboard players who often played on gospel sessions, and even then the vocalists were under no obligation to join.

Except that they probably sang unaccompanied, we can say nothing about the Heavenly Wonders, because their sides have never seen release. Hayes and Laughton can only cry "No details."

Could the Golden Tones have been the same group that appeared at the Rhumboogie Café (on a bill headlined by Dinah Washington) in April 1946? Almost certainly not—at least 8 different gospel groups that have left traces on record were called the Golden Tones.

According to Hayes and Laughton, this group of Golden Tones, making its first trip to a studio, consisted of Robert Barner, James Trusk, and Robert Fitzpatrick, all singing lead at various times, with accompaniment by Loy Oliver, tenor, Wilbert Webster, baritone, and George Taylor, bass. The group was perfect for a company in trouble with the Union because it performed a capella. Norman McQueen was a DJ, then in his 50s, who had sung in a gospel group when he was younger. He thought he could help the Golden Tones, all much younger, improve their style, which he considered too smooth. He lined up the Chance session and directed the group at the session, also taking a tenor lead on "God Is Love." Despite the strong performances on Chance 5000, the group did not record again for nearly a decade. A later, smaller edition of the group, featuring James Trusk and Loy Oliver, recorded four sides for St. Lawrence in 1965 and a couple more for Halo in 1965 or 1966; these included accompaniment on the organ and a rhythm section.

The Southern Clouds were another a capella group. According to Hayes and Laughton, they consisted of Henry McLaughlin, Douglas Price, and Barney Pool, who all sang lead at one time or another, Jonas Bobo, tenor, H. Bankhead, baritone, and J. D. Price, bass. They laid down four sides, probably in January 1952; two were released in June on Chance 5001, which we do hope to hear some day, and two were left unissued, identified on Sheridan's list by fragments of their titles.

Although the Southern Clouds were an entirely different group, they too were under the wing of Norman McQueen, as we learn from the label to "Sit Down Servant." We are indebted to Big Joe Louis for the label copy on this very rare release.

Chance 5001 was reviewed in Cash Box on June 7, 1952 (p. 28), and in Billboard on June 14 (p. 66; the 78 was listed in the same issue on p. 62).

We actually know something of Naomi Baker's doings in Chicago during the early 1950s. She was an organist. We expect she joined the Union because she did not do all of her performing in churches. Indeed, Local 208 posted her "indefinite" contract with radio station WSBC on February 16, 1950. On May 4, 1950 she posted an indefinite contract with the Church of God in Christ; another indefinite contract with the same church posted on February 15, 1951. There is enough evidence of activities in Chicago to dispel a couple of notions: that her February 1952 sides were recorded in Los Angeles, or that she sang on them. The the labels to Chance 5002 and 5006 both read "Spiritual | Organ Solo" and 5003 says "at the Organ." Her name is spelled "Naomi" on the Local 208 contract list (we admit this is a less than infallible source), "Naiomi" on the labels to her first two Chance releases, and "Naomi" on the labels to the third.

At the time, gospel organ instrumentals weren't terribly common. Chance had some hopes for her sides, because the company released all four from her first session. Sheridan waited, however, until he had the green light from the AFM again. Chance 5002 was reviewed in Billboard (Nobember 22, 1952, p. 30); "Love Lifted Me" was described as "bright and lively" and as a "jazzy spiritual item." Cash Box ran its review on the same date (p. 22). Baker occasionally played piano with one hand and organ with the other, as passages from 5002 and 5003 indicate. The company brought Baker back for a second session, but she didn't catch on the way Maceo Woods would soon be doing for Vee-Jay.

Chance was a 78-only label until the summer of 1952. And like the Chess brothers, Sheridan assumed that 45-rpm jukeboxes wouldn't carry gospel records and that gospel buyers wouldn't own the latest playback equipment. So even after his other series switched over, there would be no 45s in the Chance 5000s.

Although the company had to wait until May for new sessions with Union musicians, it was now actively seeking visibility. In March, it put out Chance 1112, one side of which featured Schoolboy Porter's band (without crediting them on the label). In April, it released Chance 1114, with "Soft Shoulder" and "Rolling Along" from the same session of July 1951 (see the ad and the review in Cash Box, April 19, 1952; Billboard caught up with the record in May, with a listing on May 10, p. 35, and a review on May 17, p. 46).

There was also some kind of pact with Bud Brandom, of Frederick and Brandom Music. Sheridan was dipping a toe into the pop market, which was Brandom's number one interest (and Joe Brown of JOB already had a business connection with Brandom). The only Chance release after 1114 to revert to the old no-publisher procedure was Schoolboy Porter's 1117. Derived from Porter's 1951 session, we figure 1117 was actually planned around the same time as 1112 and 1114. In the end, Chance 1119, fresh from Schoolboy's 1952 session, was pushed to the head of the queue and 1117 allowed to lag a month or two behind it. The production copies of the 78 for 1117 carry no publisher credits on either side. On the DJ copy of the 78 (Sheridan had just started doing DJ copies, a practice he didn't stick with for long), the standard "Sentimental Journey" still has no publisher listed but Porter's "Fire Dome" shows "Fredrick" Music. (If there was a 45 for 1117, we haven't spotted it.) Chance 1120 and 1121 also carried credits to Frederick Music.

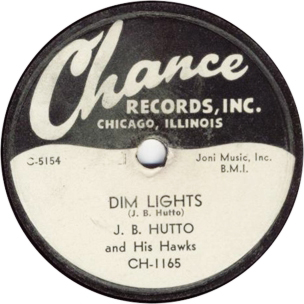

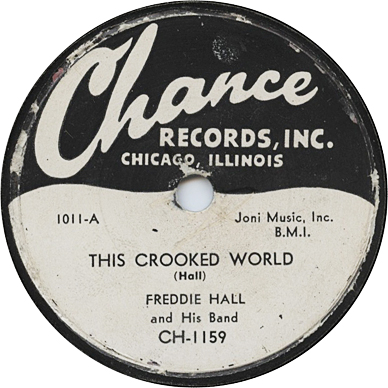

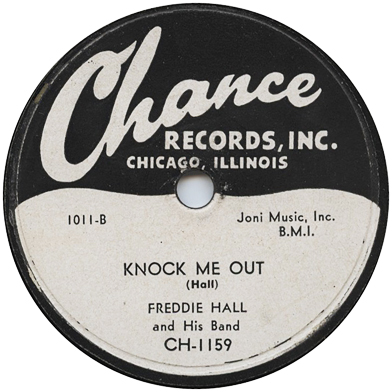

At year's end, Sheridan shifted over to Joni Music, which would be the house publisher for the rest of his company's existence.

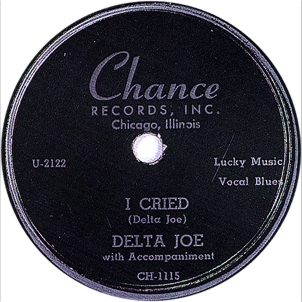

In March or April 1952, Art Sheridan also snapped up two blues releases from now-defunct Chicago independents. He picked up a single by "Delta Joe" (Sunnyland Slim) and Baby Face Leroy Foster that had been out for a hot minute on Joe Brown's Opera label. Chance 1115 doesn't seem to have sold much, but Sheridan would be making further transactions with Joe Brown.

Sheridan also resuscitated the two sides that Little Walter Jacobs had cut in 1947 for Ora Nelle, with Jimmy Rogers and Othum Brown in the back of a Maxwell Street record shop. A "Little Walter J." single was out in May (reviewed in Cash Box, May 31, 1952). It had been recorded for OraNelle in 1947, and posed no Union issues (at least none that were ne); one side was actually by Othum Brown. Art Sheridan got Chance 1116 into circulation before Little Walter's breakout solo release on Checker 758, though of course he would spring for a a big ad in Cash Box while it was riding high in the charts (November 1, 1952).

Chance's term of banishment must have been for one year, ending April 30, 1952. Secular recording promptly resumed on May 1, with—what else?—a John "Schoolboy" Porter session. (It turned out to be his last for the label.) On "Junco Partner," "Break Thru," "Small Squall,"and "Lonely Wail," the band consisted of trumpet, baritone sax, organ, bass, and drums. There are solos on "Break Thru" from a fat-toned trumpet player (Art Hoyle again) and bebopping baritonist (Mr. Peterson, whatever his first name was); the organist has a brief solo that suggests Bird and Diz at the roller rink. The organ playing on "Junco Partner" is hipper. This is the same band that Porter recorded with on July 25, 1951, except Eugene McDuffy (still not yet known as Jack McDuff) was playing the organ. His encounter with Jimmy Smith wouldn't come for another three or four years… The final Schoolboy release, Chance 1132, paired two solo vehicles for the leader (with a little help from McDuffy). "Lonely Wail" is a variant on "After Hours," while "Small Squall" paraphrases the old boppers' vehicle, "Cherokee."

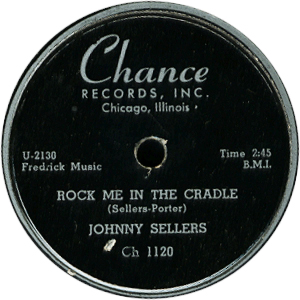

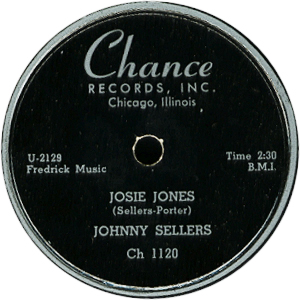

Joining in on the session was vocalist Johnny Sellers. He was the same man who recorded gospel songs (along with some secular material) as Brother John Sellers for Chicago in 1945, and gospel only for Miracle in 1946 and 1948. John Sellers was born May 27, 1924 in Clarksville, Mississippi. While in the South he performed in minstrel shows, but in Chicago by the early 1940s Sellers was singing gospel with Mahalia Jackson. By the time he signed with Chance, he had also recorded blues for the RCA Victor label in 1947 (backed by Willie Dixon), and for King Records in 1951.

Unfortunately for Chance, Schoolboy Porter was getting tired of the uncertain income from performing. With the Korean War still on, there were plenty of job openings in the military. Cash Box mentioned his departure on June 21 ("Rhythm & Blues Ramblings," p. 14), stating that Chance had "lost" him to the Navy. Maybe that was the plan, but Porter ended up in the Air Force. (He might have consulted his bandmate, Art Hoyle.) Schoolboy Porter did just one more studio session that we know of. On August 21, 1952, presumably while on leave, he accompanied Roosevelt Sykes for United—on guitar. If Sykes hadn't called on him by name during a solo, we wouldn't know he was there.

In 1958, Defender writer Al Close caught up with Staff Sergeant John Porter at McGuire Air Force Base, outside of Trenton, New Jersey ("Ex-Hampton Musician Now Air Force Great," December 6, 1958, p. 18). Porter was a member of the 750th Air Force Band. For two years he had also been leading a quintet called the Crew Chiefs; he had also taken up the trombone, which enabled the group to alternate between a tenor sax/trombone and a Jay and Kai front line. According to Close, Porter had participated in the original Air Force "Tops in Blue" show, which toured bases in Korea, Japan, and elsewhere in the Far East.

An Air Force career man with almost 9 years of service (including a 2 1-2 year stint in the Navy) Porter prefers the secure income of the Air Force to the sometimes topsy turvy economy of the civilian world of music and entertainment.

A decade or so later, Porter was stationed at Luke Air Force Base in Arizona (he is identified as a member of the 541st Air Force Marching Band, in a photo taken in 1975: http://www.afmusic.org/images/541st%20AF%20Band%201975-lg.jpg. On his retirement from military service, he settled in Phoenix.

According to Allan Chase, who played with him on one or two occasions between 1978 and 1981, Porter was for a time a member of a band called Pendulum, which was led by drummer Lewis Nash, with Prince Shell on piano and Tom Golden on bass. An item in Billboard (Al Senia, "Hines Next for Arizona Series," October 11, 1980, p. 66) mentioned a free outdoor event on September 14, kicking off the annual jazz series for the Scottsdale Center for the Arts. In front of 3,500 fans, a "freestyle jam session" was mounted by "12 top Phoenix area jazz musicians" including Prince Shell, Charles Lewis, John "Schoolboy" Porter and John Hardy. Of Porter's standing on the Phoenix jazz scene, Chase's assessment was:

Schoolboy was by far the most sophisticated of several good African-American tenor players with military ties around Phoenix […]. Schoolboy could really play changes and had great authority and a big sound. Maybe there were traces of Don Byas, Lucky Thompson, that sort of thing: post-Hawkins with harmonic sophistication, into Gene Ammons and maybe some R&B. (email communication, October 6, 2003)

Guitarist John Ehlis, who enrolled in Mesa Community College in 1983, encountered Schoolboy Porter a little later. According to an online biography of Ehlis (see http://www.jazz.com/encyclopedia/ehlis-john-anthony), "Tenor saxophonist John 'School Boy' Porter is remembered for his colorful personality and getting down to the 'feel' of the tune."

A radio broadcast from KMCR in 1983 was reportedly recorded, with School Porter (too old by then to be a schoolboy), Prince Shell, Curtis Stovall, Tom Goodwin and Ted Goddard, Jr.

School Porter was still performing occasionally in the Phoenix area in 1991, according to the Arizona Republic. He died in 2012.

As part of Sheridan's multi-stage relaunch, he temporarily moved Chance to 2009 South Michigan Avenue, next door to American Record Distributors. Billboard readers were told the company "has been formed" and was releasing sides by Schoolboy Porter, the Chanceteers, and James Williamson. More importantly, "label now has set 15 distributors and, after setting a West Coast rep, will offer national distribution" ("Chance Label New Chi Firm; Disks Released," Billboard, June 14, 1952, p. 70). Chance's annual directory, published on June 28, gave just 5 distributors for Chance, so Sheridan must have ramped up in a hurry. Less than two months later, Sheridan dissolved American Record Distributors, which he had been running since December 1949. American had carried 12 labels at times, but was now down to Chance, Aladdin, and a couple of Aladdin's subsidaries (Cash Box, June 28, p. 70).

Sheridan reorganized the firm as Sheridan Distributors, Inc., with headquarters at 1151 East 47th Street ("Sheridan Changes Firm Name—Moves Quarters," Cash Box, August 2, 1952, p. 26). Chance made the move as well, bringing the distribution arm and the Chance label into closer proximity to the South Side's "record row." An ad in Cash Box (August 2, 1952), showing the new address, announced Chance 1117 (more from the July 1951 Schoolboy Porter session, possibly a release planned earlier and delayed), Chance 1120 (John Sellers), and Chance 1121 (James Williamson); it also reminded everyone that the company was handling JOB 1007 by Eddie Boyd.

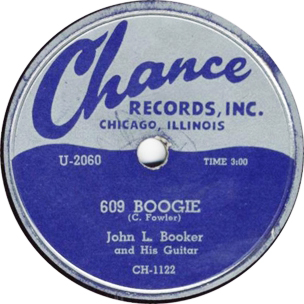

Chance 1123 was released on 45 as well as 78, as Chance made sure buyers knew (e.g., the company ad in Cash Box, November 29, 1952). Simultaneous release on 78s and 45s appears to have started with Chance 1122 (recorded in Detroit by John Lee Hooker—for 1122 you should consult our section on Purchased Masters). Around this same time, a couple of older items, such as Chance 1007, were belatedly pressed on 45s.

Sheridan was a late entrant to the format wars, not getting involved with 45s till his June relaunch. This put him months behind the Chess brothers, who had some 45s out before the end of 1951.

Subsequently most Chance (and, when they arrived, Sabre) releases would appear in both formats. But the Chance 5000 gospel series never went to 45s. An occasional later item in another series (such as Chance 3003, Chance 1158, or Chance 3021) never saw release on 45 either.

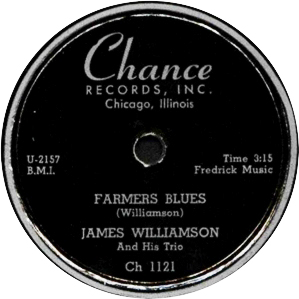

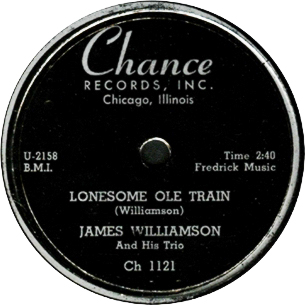

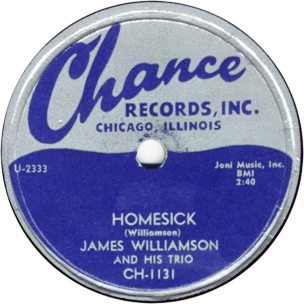

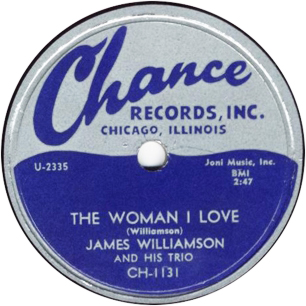

On June 12, the company did its first recordings on a downhome bluesman, the bottleneck guitar player and singer James Williamson, who would become known as "Homesick James." These sides were recorded at the old RCA Victor Studio at 230 South Michigan, and not at the ever reliable Universal, which is why there is a different master number series. (One source of puzzlement: two sides have matrix numbers in the U series—these were applied to material from the first Williamson session later on—but not in the original matrix number series. It is possible that these are retitlings of material that is already listed with matrix numbers in the 100 series.) Joe Brown, who would lease or sell sides to Chance when he lacked the finances to put them out on his JOB label, brought James Williamson to Sheridan.

Williamson was born John William Henderson on May 3, 1914, in Somerville, Tennessee. He played on Beale Street in Memphis during the 1930s. He first moved to Chicago in 1937, recording a little for RCA Victor and playing some local clubs. He returned to Memphis during the war years, but in the early 1950s settled again in Chicago. Williamson played a bit on Maxwell Street, and toured with the Elmore James band. His first session was not a great success musically; there wasn't enough rhythm support to keep him and pianist Lazy Bill Lucas on the same page. Just one single came out on Chance from this session, and Williamson would have to wait till his next, much-improved outing in January 1953 to earn his nickname. The first reasonably comprehensive release from this session had to wait till 1977, when P-Vine Special, licensing them from Sheridan, put out a whole LP of Williamson's Chance tracks in Japan. Williamson later recorded for Prestige, Delmark, Earwig, and lastly Icehouse (in 1997). He died on December 13, 2006, in Springfield, Missouri.

Not long after Chance was officially reactivated, Ewart Abner, Jr. joined the firm. Abner was born the son of a minister in Chicago on May 11, 1923. Related Sheridan, "At the time I met Abner he had graduated from college as an accountant. In those years a black man had a hell of a job trying to get a position as an accountant. He became our accountant in the distributing business and in the record plant, and ultimately for a while ran the pressing plant. After we closed the pressing plant, Abner became very much involved in Chance. In those years Leonard and Phil [Chess] were their own producers and A&R men and I was my own producer and A&R man. Abner was basically the finance man, in the sense of being the accountant guy, bookkeeping and so forth." Eventually, Abner would become the president of Chance, though it was Art Sheridan who talked to the trade papers and signed most of the checks.

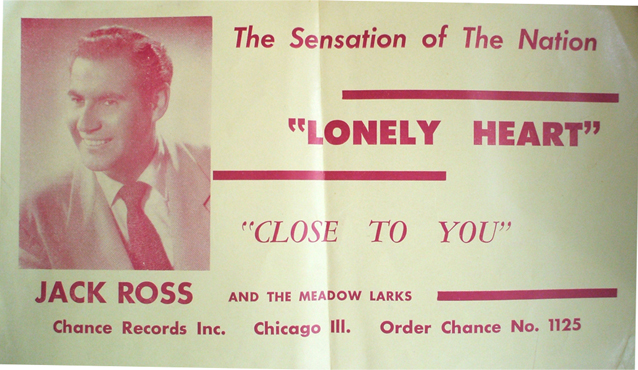

Most likely in August, Sheridan put together a pop session for a singer named Jack Ross. Ross, whose real name was Jack Rosen, was born on July 4, 1923, on a ship in New York Harbor as his parents were immigrating from Europe. He began singing with bands in high school and after graduating toured various small clubs in the Midwest. During World War II, Ross sang for several years with the USO. After the war, he worked for radio stations in Chicago. He was on the staff at WGN and had a show on the ABC network called "Black Night." Around the time of his Chance session, he was doing "The Jack Ross Show" for WIND. During this period, Ross also worked as a model in TV commercials and print ads in Chicago.

A vocal quartet called the Meadowlarks, also active on Chicago radio, were brought in for the session. The next year, they would appear again on the first Buddy DiVito session (see below), and one of the group's members, Elaine Rodgers, would receive a solo outing with Chance. The Meadowlarks, originally 3 male vocalists and one female, came together in Chicago, in 1948 or 1949, to do radio work. Maury Jackson, who had been on WBBM from 1946 through 1948 with Gloria Van and the Vanguards (also known, when a different company was sponsoring the show, as Cinderella and Her Fellas) was one of the original members. He met Elaine Rodgers when she auditioned, and they married not long afterward (see http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2012-03-21/news/ct-met-jackson-obit-20120321_1_jazz-quartet-lombard-popular-jazz). By 1949, the Meadowlarks were appearing regularly on WBBM (scripts with speaking parts for Elaine Rodgers have survived for shows they did on May 26 and June 10, 1949, both with Charlie Agnew's band) and on CBS network radio. Their show, "The Life of the Party," ran Monday through Friday, 3:15 to 3:30 each afternoon. Later they did some work for WGN.

The group got occasional studio work. They appeared on a side by Jerry Murad's Harmonicats (released on 78 as Universal 156, when that label had a deal with London, so the single also appeared on 45 as London 30,002). The London single came out in December 1949, the Universal probably a little earlier. In 1950 (the Chicago Cubs officially adopted the song on June 16), they cut "Come on You Cubs, Play Ball!" for a short-lived Chicago company called North-American, run by former Vitacoustic executive George Tasker. The band was directed by Bernhard "Whitey" Berquist of Geneva, Wisconsin, who had composed the tune in 1937. Berquist did a lot of radio work for NBC, most commonly on the Farm and Home Hour, but he'd conceived the Cubs number with a Swing band in mind, and that's what he led for the date.

The Meadowlarks appeared on one or two of the four legendary sides that Lurlean Hunter made for an obscure label ironically named Major (April 1951); the Majors got reissues on JEB (August 1951), which unfortunately might have been even more obscure. The group also got onto one side of a Ralph Marterie single ("You Better Stop Telling Lies about Me," Mercury 5657, reviewed in Cash Box, June 16, 1951, p. 8).

At some point (the Cubs fight song definitely still featured the original lineup), the Meadowlarks become a quartet of two female and two male singers. We're not sure which edition of the group accompanied Jack Ross, but in 1953 and 1954 the Meadowlarks were Maury Jackson, Marie Renaldo, Elaine Rodgers, and Bob Bleznick. Their movements, when they were not recording, are hard to trace because they had chosen such an obvious name for a "bird group." These Meadowlarks had no connection with, say, Don Julian and the Meadowlarks, who recorded for Dootone in 1955.

One of the composers of "Lonely Heart" was Al Trace, a veteran leader of "sweet" bands and studio orchestras in Chicago (see below for a Chance session that Trace directed). Two sides, out of the four recorded, appeared on Chance 1125 in October 1952. Jack Ross kept the session tapes, including the two unissued sides.

In later years, Ross moved to Florida. He continued to sing at clubs and events well into his 70s. He also made an acting appearance on an episode of "America's Most Wanted." (Our thanks to Darril Wilburn, who provided us with a brief bio of Jack Ross in an email of May 19, 2006; by that time, Ross had retired.)

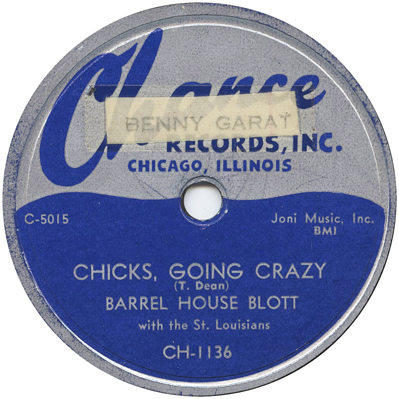

1125 is a transitional release in a couple of ways: in a few months Sheridan would be opening a separate Chance 3000 series for pop records, and he was experimenting with his label design. What had been a silver on black label was changed for this one release to silver on dark blue. After Chance 1125 the silver on dark blue color scheme would be retained but the graphics would be completely redesigned.

In September 1952, Sheridan got an R&B education at a local radio station. Said he, "Jesse Coopwood was a deejay at WWCA in Gary. I did a stint on his station when he went on vacation, because I wanted to learn what it was like to be a disc jockey. I did three months out there, and it was quite an experience. I learned a lot."

The last quarter of 1952 saw robust recording activity, starting with the eight-side session by Johnny Sellers and a Four Shades of Rhythm session in the early fall. And Chance completed its transition to the now celebrated silver on blue label design (which looks great, and falls easily on the scanner).

John Sellers' second session was a marathon—eight sides in September, all blues. With Schoolboy Porter away in the military, Sellers was now backed by the band of local trumpet player William Little (1912-1991), who as King Kolax had a 35-year career on the Chicago scene. To a far greater extent than Kolax, who would drop out of the accompaniments if the singer or recording director found him too obtrusive, the star of the band on these outings was smooth tenor saxophonist Dick Davis (1917-1954).

Four sides ended up being released, on Chance 1123 and 1138. Chance 1123, "Mighty Lonesome" b/w "Blues, This Ain't No Place for You," got a big advertising push from the company: ads in Cash Box on November 8, 1952 (p. 9) and November 29 ("Available on 45's as well as on 78's"). It showed up again as one of four Chance and JOB releases in a holiday ad (Cash Box, December 27, 1952).

After his Chance sessions, Sellers moved to New York and became involved in the folk club scene. He built a career on a similar model to Big Bill Broonzy, Josh White, and the Reverend Gary Davis, presenting a repertoire that melded folk, blues, and gospel. He made LPs for Vanguard (1954), UK Decca (1957), and Monitor (1959). Sellers died on March 27, 1999, in New York.

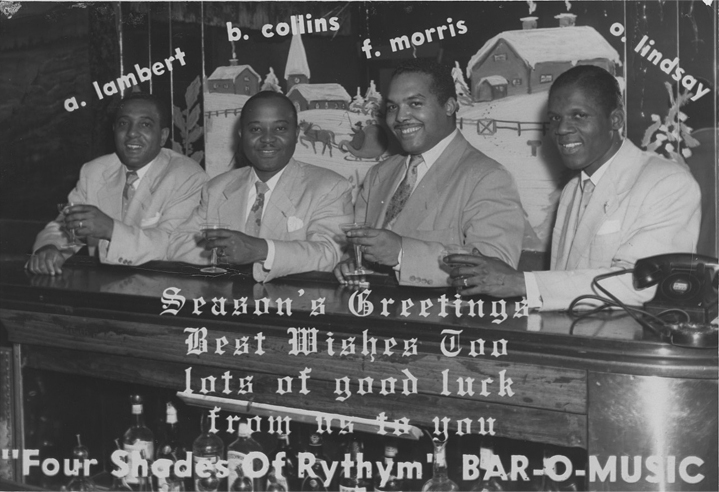

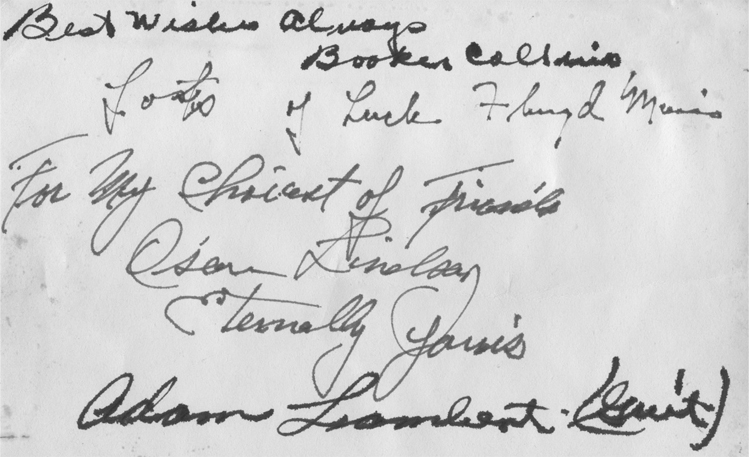

The Four Shades of Rhythm were a vocal/instrumental combo that had originated in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1945. The group had been playing in Chicago on and off since 1946 and made their first recordings there for Vitacoustic, in two sessions in December 1947. In March 1949, Old Swing-Master released two sides that had been cut for Vitacoustic and impounded by United Broadcasting Studios when that company went under; the Four Shades had a local hit with the "My Blue Walk" and "Baby I'm Gone." These two tracks are probably the same ones listed here. (Apparently the deal did not include their other sides for Vitacoustic, four of which had appeared on Vitacoustic 1005 and Old Swing-Master 33.)

The Four Shades continued to play and tour, using Chicago as their base of operations. Around the end of 1949, Oscar Pennington was replaced on guitar by Claude Williams. Williams was replaced in his turn by Adam Lambert, formerly of the Cats 'n Jammer Three and the Bill Samuels Trio, when Samuels broke up the trio in 1950. In 1951, bassist Eddie Meyers left the group; he was replaced by veteran bass player Booker Collins, who became available when the Floyd Smith Trio broke up. In 1951, Adam Lambert was replaced for a spell by Emmett Spicer, best known for his prior service in Prince Cooper's trio. Not long after Booker Collins joined the group, the Shades cut no fewer than 16 sides at C. H. Bomgardner's Custom Sound Recordings in Evanston, a suburb north of Chicago (see the Appendix for these). Ranging up to 5 minutes in length, the sides were just semi-professionally recorded and never commercially issued, but they give today's listeners the only comprehensive view of the group's repertoire.

Floyd Morris briefly took over the piano bench after Ed McAfee left the group, and Adam Lambert returned. By the time the Four Shades of Rhythm recorded for Chance the group had changed pianists again. The quartet now consisted of Oscar Lindsay (lead vocals, cocktail drums), Adam Lambert (guitar), Booker Collins (bass), and Ernie Harper (piano). The newest member was a veteran of the Four Blazes who had been playing solo from 1948 through 1951. Lindsay was the only member to have been with the group in Cleveland.

The group recorded a ballad, "Yesterdays" and a jump tune, "So There." for Chance. It appears the unissued side "Everything I Have Is Yours" was acquired from Old Swing-Master. We do not know the original Vitacoustic master number, which came from one of two or three sessions in December 1947. Bernie Besman was partnering with Vitacoustic on its R&B series and he applied his own matrix numbers before dealing 13 sides by the Four Shades to Modern (which never did anything with them). Their single, Chance 1126, was released in November. Whatever it pulled in by way of sales (it is very rare today), the company did not see it as worthy of further promotion. Chance 1126 received a single company ad in Billboard (November 8, 1952, p. 48). A week later, the company ad was for Jo Jo Adams' Chance 1127, and 1126 did not resurface in other company ads that we've seen.

The Four Shades of Rhythm continued to perform after their Chance session. The group's last recording was done for Tommy Jones' Mad label in 1957. A 1960 remake of "A Hundred Years from Today" for Apex was a vehicle for Oscar Lindsay with strings and chorus; it used the Four Shades of Rhythm name, but the group no longer existed.

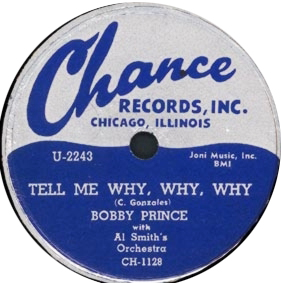

In October and November, there was extensive session work using the Al Smith orchestra. Al Smith was able to step in because Chance needed a new house ensemble; Schoolboy Porter was going wherever the Air Force sent him.

Albert B. Smith was born in rural Bolivar County, Mississippi, on November 23, 1923. After a stint in the Merchant Marine, he arrived in Chicago in 1943. In 1945 he put together what has been called a "bebop" band, but sensing how the commercial winds were blowing, he broke it up in 1952 and founded the R&B unit that can be heard on these sides. Al Smith had no great chops on his chosen instrument; drummer Charles Walton said, "He held the bass... OK, he played the bass—but he didn't tune it first." Many other musicians have slighted his instrumental prowess, while paying tribute to his adeptness at landing gigs and cutting deals. For the kind of money that Smith could pull in, the best musicians in town were eager to work with him.

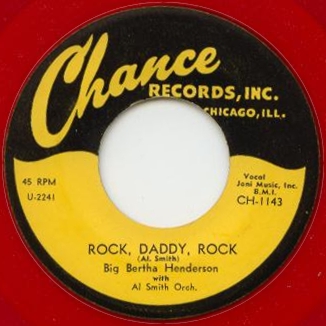

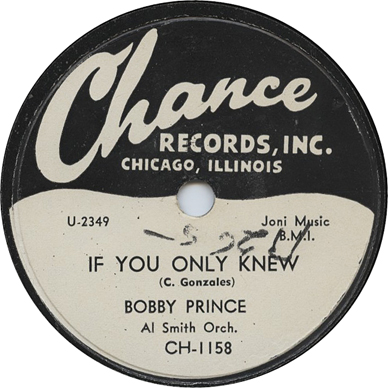

Al Smith's job was usually to back a vocalist or a vocal group; he didn't get a lot of releases under his own name. But Chance 1124, which was one of four releases featured in a Cash Box ad (December 27, 1952), was under Al's name. It coupled an instrumental ("Slow Mood") with a not-quite-instrumental of "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes" (Bobby Prince added an uncredited falsetto vocalise.

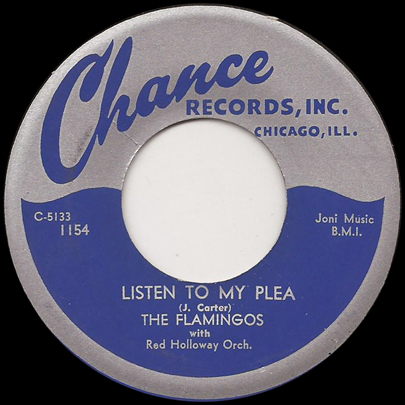

For the session with singer Big Bertha Henderson, whose "house-rockin'" appearances were advertised at Club Evergreen and Martin's Corner in the fall of 1952, Smith brought along two of the best tenor saxophonists in town, James "Red" Holloway (1927-2012) and Oett "Sax" Mallard (1915-1986). His rhythm section was filled out by Billy Wallace on piano, William "Lefty" Bates (1920-2007) on guitar, and Leon Hooper on drums. For the Bobby Prince session, he brought Red and Lefty back, along with Eddie Johnson (1920-2010) on tenor, the indispensable McKinley "Mac" Easton (1914-1986) on baritone sax, and Clarence "Sleepy" Anderson on piano. About Bertha herself, we know hardly a thing. In December 1953, Herman Lubinsky, during a two-week excursion to the South, signed her to Savoy; a release (as Big Bertha) promptly followed (Billboard, December 12, 1953, p. 18). Some correspondence with her that was preserved in the Savoy files gives a home address in New Orleans.

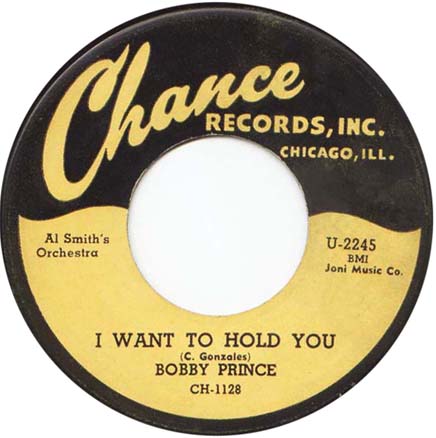

Bobby Prince, whose real name was Charles Gonzales, started in show business around 1948, when he joined the Hot Lips Page band in Cincinnati as a singer. He stayed with Lips for about a year and then went solo. He launched his recording career in 1950, recording some sides for Philadelphia-based Gotham. His most notable recording for Gotham was a rousing jump, the self-penned "Hi-Yo Silver." Gotham 234 was released in June 1950 (it appeared on the list of records received by Billboard on June 24, p. 32). The session was produced in Chicago by J. Mayo Williams, who, for the time being, had wound up his Harlem/Chicago/Southern operations and was taking some time off before starting up a new Ebony operation.

In November 1952, billed at Joe's Deluxe Club (6323 South Parkway) as "golden voice jump-blues vocalist," he was still performing as Charles Gonzales. He apparently entered the recording studio with the Al Smith band as Charles Gonzales and left it as Bobby Prince. Chance 1128, "Tell Me Why Why Why," seemed to garner the singer some acclaim when it was released in January 1953, and Chance pushed the single with some of the largest trade ads in the label's history (for instance, in Cash Box on February 7, 1953). Bobby's unannounced appearance on "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes," which he scats in a spooky falsetto while Eddie Johnson decorates the melody, is also memorable. Chance would make considerable use of Prince's compositional talents, using four of his songs for Flamingos sessions.

Toward the end of the year, Sheridan added the famed gospel group, the Pilgrim Jubilees, to his roster. In fact, they made their first appearance on record for Chance (as the Pilgrim Jubilee Singers). This particular version of the group consisted of Elgie C. B. Graham (lead), Cleave Graham (alternate lead), Clay Graham (tenor), Monroe Hatchett (baritone), Major Roberson (baritone), and Kenny Madden (bass). The Grahams were all brothers. According to Alan Young's book, The Pilgrim Jubilees (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), the Pilgrim Jubilees were formed in 1944. The group broke up in the late 1940s, but according to Young it was reconstituted in Chicago in 1952. Young lists the recording date for the Chance sides as January 1953 (noting how their session fits right in between the Bobby Prince and the Lou Blackwell in the matrix series, we have revised that to November or December 1952). Young also says the label mistakenly lists "Just a Closer Walk with Thee" as "Just a Walk with Thee"; we'll take his word for it, but it would be nice to see a copy of Chance 5004. Elgie Graham took the lead on "Happy in the Service of the Lord" and Cleave Graham sang lead on "Just a."

They went on to record (as the "Pilgrim Jubilee," soloist identified somewhat ambiguously as "C. Graham") for the N. B. C. label, which wasn't what you're surely thinking; the initials stood for Northern Brightrecord Corporation. Probably in the second half of 1953, the Pilgrim Jubilee Singers cut "Angel" and "Lord, I Have No Friend Like You" for release on N. B. C. 2003 (Young's book says it was 1954). Arthur Crume was added on guitar. There may have been some business connection between Chance and the twin gospel microlabels, N. B. C. and C. H. Brewer, which shared an address at PO Box 560, Chicago 90 Illinois. Several of the known releases on C. H. Brewer show matrix numbers in the U-3100s. JOB, which was allied with Chance from mid-July 1952 through the middle of October 1953, later released a single by the Norfleet Brothers that carried NBC matrix numbers and also appeared on C. H. Brewer. And the Kelly Brothers' single on C. H. Brewer was recorded in May 1956, amidst actvity for the Abco label of which Joe Brown was co-owner. Bo Sandell, who alerted us to the connection, also notes that the N. B. C. and C. H. Brewer labels look a lot like the labels that Chance used.

The Pilgrim Jubilees enjoyed a long career thereafter; they went on to record for Specialty (1955), Nashboro (1957-59, 1976-79), Peacock (1959-75), Savoy (1980-84), and finally for the Mississippi-based Malaco (1987-2000). Any of their records for any of these labels will be much easier to find than their one single on Chance.

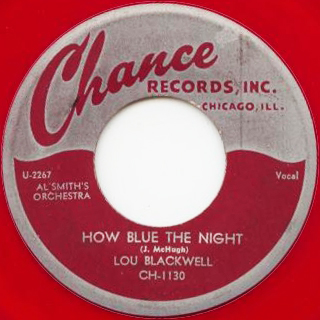

Al Smith also backed lounge singer Lou Blackwell. By this time, Blackwell had a right to feel snake-bit. He had cut a never-issued session for Aristocrat in August 1949; a never-issued session for Chess in May or June of 1951; and two more tracks, unreleased till the 1990s, during Tab Smith's second session for United on October 24, 1951.

On what appears to have been Lou Blackwell's final session, Al Smith put together a larger band, probably consisting of Paul King (trumpet), Red Holloway (now on alto sax), Sax Mallard (tenor), Mac Easton (baritone), Billy Wallace or Clarence "Sleepy" Anderson (piano), and Leon Hooper (drums). Blackwell finally got a record released, Chance 1130.

The impending release got a blurb in Sam Evans' column in Cash Box (November 29, 1952, p. 21). Evans compared Blackwell to Billy Eckstine, but also noted that "Man has about eight sides that have never been released." The single come out on 78 and 45 rpm (blue-label 78; red-label 45, as though Sheridan was anticipating his pop series) in February 1953. It was reviewed in Cash Box on February 28 (p. 22).

The other sides from Lou Blackwell's Chance session shared their fate with everything he had done previously. They are still unreleased today.

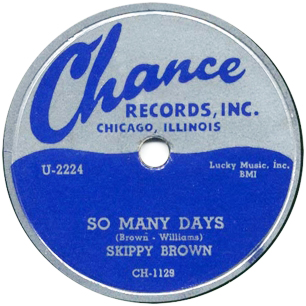

We still know little about the Skippy Brown release. The late George Paulus described Brown as an uptown blues singer. The record got a tepid review in Billboard (February 21, 1953, p. 54). For "So Many Days," the comment was "Both the chanting and the material are fairly mundane. Most attractive ingredient is the bop-sounding ork background."

The composer credits to both sides were shared with one "Williams." Brown's only other known recording was done in 1954, for an eccentric 10-inch LP of Christmas songs that came out on J. Mayo Williams' tiny Ebony label. We infer that Brown recorded the single for Mayo Williams, who sold or leased the masters to Chance.

Now that we've been able to hear Chance 1129, we can report that Skippy Brown was a female singer with a rather heavy alto voice who preferred blues. She was accompanied by trumpet, alto sax, two tenor saxes, piano, bass, and drums. "So Many Days" includes a trumpet solo and and, yes, an alto sax solo by someone who knew his Charlie Parker. "Tale of Woe" uses a lot of words, so it has a piano intro consisting of one arpeggio, and no room for solos.

The only newspaper notices we've found for Skippy Brown came from a single run at the Flamingo Room of the Hotel Charles in Decatur, Illinois. She was part of a revue featuring a comedian named Lee Norman (the "Magnificent Idiot") and dancers (the dance lineup turned over about halfway through the run). The revue started in mid-November 1953 and appears to have continued through New Year's. The first ad (The Decatur News, December 4, 1953, p. 20) identified her as a "Popular Recording Artist." As did several ads that followed. Only the very last display ad (The Decatur News, December 19, 1953, p. 9) referred to Skippy Brown's release on Chance. Well, they got it in.

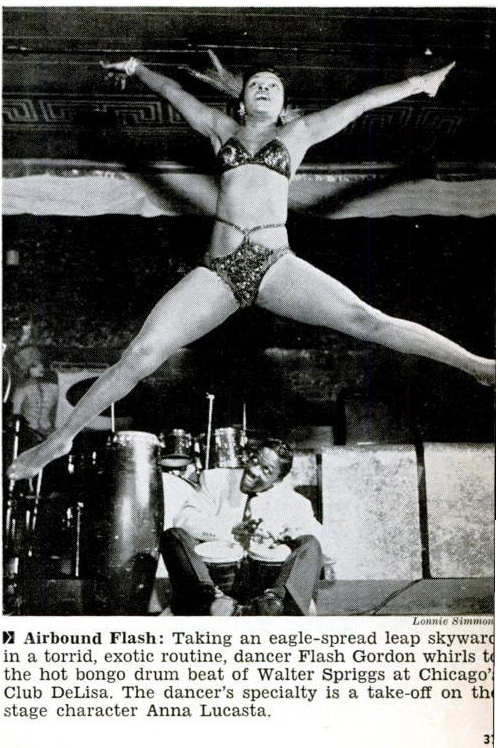

October also saw a session with uptown blues singer and man of many tail coats Jo Jo Adams, backed by the band of bebop trumpeter Melvin Moore, who had previously recorded for Sunbeam and for his own GloTone label. At this time, Adams and Moore were ensconced at the Flame Show Bar (809 East Oakwood), billed as "The Jo Jo Show, starring Dr. Jo Jo Adams, Bennie Pittman, Laura Watson, Melvin Moore's Band." Besides singing his specialties nightly, Adams served as MC at the Flame, telling many dirty jokes.

Jo Jo Adams was born in Alabama, somewhere around 1918, and died in Chicago in 1988. Originally a dancer, he broke in at the Club DeLisa and made his first recordings with Floyd Smith's group for the Hy-Tone label in December 1946. He followed up with 6 sides for Aladdin in 1947, which were recorded in Los Angeles with the Maxwell Davis band, and 6 more for Aristocrat, which were done in Chicago in 1947 and 1948 with Tom Archia's All Stars. Though he enjoyed a run of several years at the Flame and would remain on the scene well beyond that, he would record just one more session, for Parrot in 1953.

Chance 1127 was advertised in Billboard on November 15, 1952 (p. 62) and reviewed in the issue of December 20, 1952 (p. 30). It was one of four Chance and JOB releases advertised in Cash Box on December 27, 1952. Adams was a reliable blues shouter, albeit somewhat stereotypical in his routine, which often featured the same tune with different partly improvised lyrics. These two sides with the band he had been working with every night are his very best, well articulated rhythmically and jumping with vitality. Moore's nimble trumpet contributions are ably assisted by Harold Ousley on tenor sax, Dave Young on baritone (his usual instrument was tenor, and he was probably added just for the studio date), Eddie Baker on piano, Sylvester Hickman on bass, and Earl Phillips on drums. The horns mostly riff, but Harold Ousley, who was making his first appearance on record, adds an intense solo to "I've Got a Crazy Baby."

Most likely Al and company also backed R&B singer "Chubby" Newsom (she was not chubby, her last name was regularly misspelled as "Newsome," and her band was often billed as Chubby and Her Hip Shakers). Thanks to Marv Goldberg's research, available at http://www.uncamarvy.com/ChubbyNewsom/chubbynewsom.html, we know that the singer was born Velma Celestine Williams, on January 27, 1920, in Wilburton, Oklahoma. She was the daughter of Leona Williams and Dan Latham. In January 1937, before she turned 17, Velma Williams married Carl Allen Newsom, Jr., in Oklahoma City. By 1940, Velma Newsom was living in Detroit and separated or divorced from Carl Newsom (she would be married at least three more times). She began getting gigs in Detroit, as Velma Newsom, in 1941. In August 1944, still in Detroit, and on her second marriage, she started going as Chubby Newsom (just why, we don't know). Into 1948, she performed in Detroit, or in Indianapolis, or Buffalo, or Dayton, Ohio. Not long after she arrived in New Orleans, in October 1948, Paul Gayten took in her act and got her signed to DeLuxe, leading to her first recording session, which took place in New Orleans in November 1948. Her first DeLuxe single featured "Hip Shakin' Mama," which became her signature number; it was also released on Miltone under a deal then in force. "Hip Shakin'" was all about her dance moves, not her body type. In 1949, she went on a long tour with Roy Brown, another DeLuxe artist. She got two further singles on the label. But when Dave and Jules Braun left DeLuxe in August 1949 and joined Fred Mendelsohn to form Regal, Chubby Newsom was one of the DeLuxe artists they took with them. Newsom made two sessions in New York for Regal, resulting in three releases before the company folded in October 1951. She also appeared on an airshot, from Birdland with Miles Davis, that was commercially released many years later. From April 1951, a live broadcast with Paul Gayten's band at a New Orleans club was recorded and retained by Fred Mendelsohn; it eventually got a release on a P-Vine Special LP. As with some other Regal artists, the Braun brothers and Mendelsohn made sure that Newsom did not go back to DeLuxe (now completely controlled by Syd Nathan) when Regal closed, but she wasn't picked up by another company. In October 1952, she supposedly signed with RCA Victor, but if she cut anything for Victor, it was never released—and in December she was cutting instead for Chance.

December is our estimate, at least, of when the Newsom session took place. We figure that Al Smith's band was on it, but we haven't heard any of the sides and don't know the personnel. On January 10, 1953, Cash Box (p. 19) noted that Chubby Newsom was working The Orchid Room in Kansas City. The blurb also noted that she was "formerly with RCA Victor, and now out on Chance record." She'd recorded for Chance, all right, but the trades were generally careful not to announce a record as released until it actually had been. Was something planned and then pulled back at the last minute? In fact, the very next item in Cash Box's Chicago coverage declared that "an early package being talked about for spring promotion will include Al Smith and his band, with Chubby Newsome and Charles Gonzales. The latter will hit the record stands under the name of Bobby Prince." The Bobby Prince reference was to Chance 1128, which really was being released. The notice reinforces our surmise that Al Smith's band was on Newsom's four tracks. But, for whatever reason, Chance never released anything by Chubby Newsom.

In June 1953, Newsom teamed with Alberta Adams, whom she knew from years on the Detroit club scene, to form a duo called the Bluzettes. Chess recorded Alberta Adams as a solo artist, but didn't pick up the Bluzettes. The Bluzettes (largely) kept together through March 1955. Chubby Newsom's last record was a single cut around February 1957 for the Winley label. It had a rock and roll sound, courtesy of a band led by David Clowney (soon to be better known as Dave "Baby" Cortez). Her last advertised gig that Marv Goldberg has been able to locate was in Kansas City in 1962. Eventually (around 1980) she moved from Detroit to Kansas City. Velma C. Newsom died at the Shawnee Mission Medical Center in Kansas City, on September 13, 2003. She was 83, and most probably had not sung professionally since she was 42.

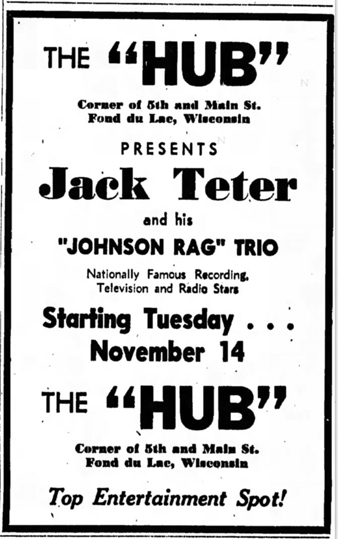

As the end of the year approached, Chance picked up a session by Jack Teter, a musician with a long and varied history. He was the only Chance artist who had distinct prewar and postwar recording careers.

John J. Teter was born on January 6, 1902, near Granger, Missouri. His first instrument was the banjo; he got his start playing barn dances in the Ozarks with a blind fiddler. He soon discovered that audiences liked his smooth tenor voice. In 1926, Jack Teter was in Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minnesota, where he appeared on local radio. In 1927, he was working with a band in Superior, Wisconsin. In 1929, he joined Bill Carlsen's Orchestra, a Milwaukee dance band, playing the banjo and singing; he would be based in Milwaukee for the rest of his life. Early in 1930, the Carlsen band recorded in Grafton, Wisconsin, for Paramount. Teter was called back in February 1930, where he cut two tracks with a "hillbilly" trio whose other members were Frank Welling and John McGhee. In April 1930, he cut two pop songs as a solo act; he was now playing guitar. The 1930 sides appeared both on Paramount and its dime-store subsidiary, Broadway. As the company was on its last legs, Teter did two more sessions for Broadway, in March and June 1932, including versions of "Just Friends" and "All of Me."

Teter went to work for WTMJ, the Milwaukee radio station, eventually getting his own 15-minute show called "The Song Doctor"; he also directed talent contests. For instance, the Racine Journal-Times (August 14, 1934) had Jack Teter's Playboys doing a half hour show on WTMJ at 11:30 on Wednesday mornings. From 1934 to 1936 Teter led the Isle of Dreams Orchestra, whose instrumental lineup, from the reports we have, points to the polka-Swing hybrid then prevalent in Wisconsin.

Nearly 17 years after his last trip to the studio, Teter signed with a new small Chicago label called Sharp. Operated by James Martin, a record distributor who in those days catered to white record buyers in the Midwest, Sharp opened for business on May 1, 1949. Sharp's model was to sign artists who Martin knew were in demand from his local experience. So Martin picked up Lee Monti and the Tu-Tones, a group that had been dropped by Aristocrat and then by Universal, but whose records on both labels had moved well for him. Teter, who had not been recording at all, joined Monti in the first cohort of artists that Martin signed (Billboard, April 30, 1949, p. 17).

A few months earlier, Teter and his trio (Bob Prouty, piano, and Bob Eberhardt, bass) had scarcely rated a mention in Billboard. The one sentence they got, noting that they had worked the summer at Devi-Bara's Dude Ranch, by the shores of Devil's Lake near Baraboo, Wisconsin, and were now at Tutz's Cocktail Bar in Milwaukee, appeared in the Burlesque column (December 13, 1948, p. 53). The writer thought that Teter played the accordion...

That all changed when Jack Teter hit it big on the Billboard chart with his first new record, a version of the venerable “Johnson Rag”. The first Sharp releases (S1 through S3) came out in July (S1 and S3 were listed in Billboard on July 23, 1949, p. 32). "Johnson Rag" was initially on Sharp S2 (getting a tepid review in Billboard on August 6, 1949, p. 105), but demand for the record helped Sharp get a deal with the London label. London was new to the United States (it was a subsidiary of British Decca) and on an aggressive quest to expand its market. "Johnson Rag" would enjoy far wider distribution as London 501. Billboard reviewed the London on September 17, 1949 (p. 109), still not expecting much from the "light innocuous style," but by November 26 (p. 26), "Johnson Rag" was number 19 on the pop charts.

To Teter's regular trio (with Prouty doubling on Solovox), the first Sharp session added a drummer. What caught attention, besides the group's unerring fusion of 1920s jazz with Western Swing, was Teter's decision to put vocals to the rag. The flip, "Back of the Yards," was more sentimental. On December 29, 1949, "Johnson Rag" and a second Teter single were included in the very first batch of 45s that London shipped to retailers ("London Joining 45 Parade," Billboard, December 31, 1949, pp. 12, 30). On January 28, 1950, "Johnson Rag" was #12 on the Billboard pop charts (p. 26), and a disk jockey in Milwaukee was boasting how he already knew, back in August 1949, how far it was going to go. In its annual survey of "Top Selling Popular Artists over Retail Counters," Billboard (July 15, 1950, p. 83) put Teter at number 30, between Arthur Godfrey and Ray Bolger. He made this list entirely on the strength of "Johnson Rag." Jack Teter was 47 years old and he finally had a hit record.