Revision note:We have added information about the release of Mercury 8016. We have updated our label photos. Saul Smaizys (email, August 23, 2016) reports an RCA Victor test pressing of the previously unknown QB-3312-1, "Cherry Red Blues." This track is from T-Bone Walker's first session of October 10, 1944. Besides confirming the existence of additional sides from that session, it nails down RCA Victor as the source for the Rhumboogies with matrix numbers in the (D#)-QB-3300 series. And the rediscovered performance is well worth restoring and releasing.

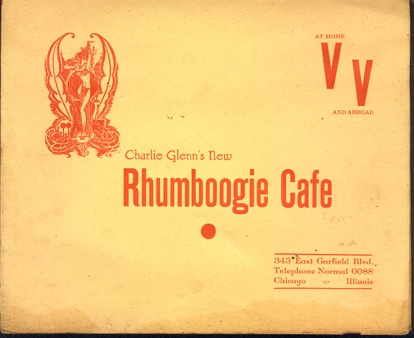

The Rhumboogie Label, which operated from 1944 to 1946, represents the earliest flowering of independent label activity in Chicago during the postwar era. Actually, Rhumboogie got a jump by starting up in October 1944, before World War II ended. The label was the product of the convergence of two remarkable events in the black entertainment industry in Chicago--the rise of the great Rhumboogie Club at 343 East 55th (Garfield Boulevard) as the most prestigious and exciting black and tan in the city, and the emergence of its prize star, T-Bone Walker, who became an entertainment phenomenon during the war years, first in Los Angeles and then in Chicago. Charlie Glenn, the owner of the Rhumboogie, decided to put out some promotional recordings on T-Bone Walker to exploit the tremendous impact the pioneer of blues electric guitar was making on the city. That was the birth of the Rhumboogie label. But first we must step back in time, to the early 1930s.

The Rhumboogie was not the first major black and tan located at 343 East 55th. The address had developed a venerable entertainment tradition in the city. Chicago was in the midst of the Depression when Dave's Cafeacute; established itself at the address in May of 1934. The club earlier had been located at 51st and Michigan, but its premises at that location were burned down by the Mob in April, according Dempsey J. Travis in An Autobiography of Black Jazz. The establishment was owned by Dave Heilig, Joseph Meyers, and Sam Swidler.

In July 1936, Dave's Café was purchased by Benny Skoller and renamed the Swingland Cafeacute;. In the tradition of black and tans, shows were presented in a revue format with elaborate productions. Skoller carried over from Dave's Café show producer Joe "Ziggy" Johnson. From the early 1930s to the late 1940s, Johnson was the premier show producer in the Midwest, working in all the top black and tans in Chicago, St. Louis, and Detroit. He was born in Chicago and his first stab of "showmanship," according to the Defender, was as cheerleader at Wendell Phillips high. He then worked as an eccentric dancer, in a boy-and-girl team with Margie Davis. He began producing shows in St. Louis around 1934, and then in early 1936 joined Dave's Café to produce his first show in Chicago.

Under Skoller's proprietorship the club featured such top-notch bands as that of Horace Henderson, Jimmy Noone, and Johnny Long. But Skoller had difficulty sustaining his club and it closed in June of 1940. Dave Helig reentered the picture and brought back Dave's Café at the address, opening on July 2, 1940; his son Mike was responsible for managing the operation. The Heiligs, too, had trouble making a go of it, and Dave's Café closed for the final time in February of 1942 (the last band to play there was led by Edward Sims, according to the Local 208 Board minute notes of January 15). But from the ashes of Dave's rose a mighty phoenix.

The Rhumboogie was launched on April 17, 1942, in one of the grandest grand openings Chicago's black community had ever seen. The opening night show featured Tiny Bradshaw and his Orchestra, plus the usual revue of comedians, dancers, and singers. (Edward Sims, late of Dave's Café, led the off-night band.) To produce the show, Charlie Glenn brought back Joe "Ziggy" Johnson, who had been in St. Louis since 1941 working at the Paradise. As limo after limo pulled up to disgorge their celebrities, the most notable being heavyweight champion Joe Louis in his Army private uniform, klieg lights lit up the sky. The Defender did not contain its enthusiasm: "The Rhumboogie club's opening staged last Friday night before a house that was packed to capacity was without a doubt the most sensational spectacle night clubbers in this or any other city have witnessed."

The Rhumboogie definitely had a Joe Louis connection. The Chicago Defender in its initial columns and news reports did not indicate that Louis had a piece of the club, but that was what has been generally assumed in the black community. Dempsey Travis asserted in An Autobiography of Black Jazz that "Joe Louis...bought the club," and "his partner was Charlie Glenn, the sportsman and Cadillac salesman." Helen Oakley Dance, in her biography of T-Bone Walker, Stormy Monday, said that "Joe Louis was the club's major backer." Defender columnist Al Monroe, complaining about the management incompetence and understaffing at opening night, said "assisting [Charlie Glenn] in management that night were Bill Bottoms, a former cabaret man, and Pat Brooks, the willing but inexperienced brother of Joe Louis." Billboard reported in February 1946 that Brooks bought into the Rhumboogie with "Glenn still holding controlling interest." By the end of 1946, however, Glenn had given up his interest (or controlling interest) in the club, and thereafter the Defender referred to Joe Louis as the owner of the Rhumboogie.

After an 8-week stand by Tiny Bradshaw, the Rhumboogie brought in Horace Henderson's band on June 9 (see the Local 208 Board minutes for June 18). Another important addition was made during the summer when Glenn hired pianist and arranger Marl Young to direct the club's floor show. Before coming to the Rhumboogie, Young had worked in a similar capacity at New Club Plantation (3520 South State), but that establishment closed on May 10, 1942, not long after Young brought a complaint against the manager, Ernest "Broadway" Bradley, for failing to pay him for some arrangements (Local 208 Board minutes, May 7, 1942, p. 3, and May 21, 1942, p. 2). We know that Young was at work in the Rhumboogie by the beginning of August, when Horace Henderson played his last week at the club; on September 17 he pressed a claim against Horace Henderson for $12.50.

Young informed the Board that he had been engaged to direct the floor show at the Rhumboogie Cafe, and that it was his understanding that half of his salary was to be paid by the management and the other half by Henderson. Hernderson failed to pay the balance above mentioned, explaining that the local had held up his money.

Even though he fought constantly with Charlie Glenn, Young would be a significant contributor to the Rhumboogie operation until the end of 1945.

Charlie Glenn made the decision of his career in August 1942, when he brought from California a veteran musician but an emerging star, T-Bone Walker, and thereby turned the Rhumboogie into a legend. For the next three years Walker was booked on extended stays at the club, culminating in recordings on the Rhumboogie label. Helen Oakley Dance explained in her T-Bone biography that Glenn and Louis had scouted Walker in LA's Club Alabam, and decided that he would be an effective attraction to build the Rhumboogie into a major club. She said, "Glenn hoped to establish the Rhumboogie as a big-league contender in the class with New York's Cotton Club and the South Side's Grand Terrace, [but was] too short of capital to hire an Ellington or a Hines."

T-Bone Walker was born Aaron Thibeaux Walker on May 28, 1910, in Linden, Texas. He made his initial recordings in 1929 in the country blues style as Oak Cliff T-Bone for Columbia. In the mid-1930s Walker moved to Los Angeles. He first attracted notices when he was used as a vocalist (but not guitarist!) in the Les Hite Band, singing "T-Bone Blues," which was released in 1940 on Varsity. Around 1940 Walker began building his reputation performing in the LA clubs. In 1942, Capitol, a new West Coast label, took notice, and recorded Walker with pianist Freddie Slack and his orchestra in two sessions, though only two sides featured Walker on lead vocals, "Mean Old World" and "I Got a Break, Baby." Remarked Bill Dahl in the All Music Guide to Blues (1999), "This was the first sign of the T-Bone Walker that blues guitar aficionados know and love, his fluid, elegant riffs, and mellow burnished vocals setting a standard that all future blues guitarists would measure themselves by." By 1942, when Glenn got Walker under contract to come to Chicago, he was creating a sensation in Los Angeles.

On August 8, 1942, T-Bone Walker opened at the Rhumboogie, headlining Joe "Ziggy" Johnson's "Dream Revue." The Dream cast included singer Rae Pearl, a dance team called the Tampa Boys, the usual line of chorines, and the great Milt Larkin Band from Texas (Larkin featured Arnett Cobb blowing great solos on the tenor sax; Tom Archia played alto and tenor saxes at different points during the engagement). After about a month, this revue was followed by "Mistery Revue" (references to mystery and mist both intended) with essentially the same personnel.

Helen Oakley Dance in her biography on Walker evoked the magic of that first stunning show in Chicago:

To wind up the production, Ziggy Joe had devised an impressive finale built around "Evenin'," the hit song of the show. In the wings a fringe of moonlit palms suggested a tropical setting. The company, in carnival attire, dimly seen behind a scrim, swayed to faint music. Down front on the darkened stage a bright spotlight focused on T-Bone in top hat, white tie, and tails. Very softly he intoned the opening stanzas of the song meant to evoke nostalgia and grief. Weaving through verse after verse was a leitmotiv inspired by the mystery and magic of night.

Reaching the finale, he addressed himself to the guitar and allowed his voice to sink to a whisper again. With a dynamic sequence of chords, he commenced an arresting cadenza. Electrified, the enchanted audience rose to its feet to applaud.

The Chicago Defender critics raved over the show. Marilyn King in the August 15 issue thought Ziggy Johnson may have created better productions, but that "no band has outplayed Larkin and no chirper has out-appealed Teabone Walker at the Rhumboogie or any other Southside nightery." Rob Roy a week later said that show "may well be rated with the best in night club history."

When Walker's run finished in October, the Larkin band continued at the club backing other acts (Larkin's indefinite contract was posted by Local 208 on October 15, 1942).

On January 15, 1943, T-Bone returned for the "Surprise Revue" (his 8 week contract, with 8 week option, was accepted and filed by Local 208 on January 21). In February he shared the spotlight with "Torch Queen" Mabel Scott, while he was billed as "Blues King." Walker's run lasted until early April; he was still accompanied by the Milt Larkin band, which continued after he left town (Larkin posted another "indefinite" contract with Local 208 on April 15, 1943) and subsequently went on the road in May. T-Bone was not at the club during the successful run by the Nat Towles band out of Omaha (August 13 through October 21, 1943). Nor did he get to work with the notorious "Dream Band" that Charlie Glenn began assembling in late October, when he hired King Fleming's old band under the leadership of local alto saxophonist Richard Overton (contract posted on October 21). Glenn had a free hand in hiring replacements because many of the young musicians in the Overton band were promptly drafted. The Dream Band boasted Eddie Johnson and Tom Archia in the sax section, and for a while an unruly second altoist named Charlie Parker. The "Dream Band" resisted its Union-imposed leader, Carroll Dickerson, and was summoned to appear in front of the Local 208 Board on January 6, 1944. The entire band was called on the carpet for a second time on June 1, 1944, on which occasion Carroll Dickerson declared the band ungovernable, was chastised by the Board for his failure to keep discipline, and was allowed to quit. Local 208's president, the imperious Harry Gray, did not like Marl Young and resisted turning the band over to him, but none of the more experienced musicians wanted the job.

Now billed as Marl Young and his Orchestra, the house band retained most of the "Dream Band" personnel, though Young instantly fired Charlie Parker and Tom Archia without notice, and had to replace the drummer and one of the trombonists (Young's leadership would finally be recognized when the band's new contract was accepted and filed by Local 208 on July 6). The band had stabilized by the time Walker returned to the Rhumboogie for another long run, from June 29 through late October. The revue included Eddie Johnson (billed as the "sax solo king"), singers George Layne (a holdover from the Milt Larkin band) and "Janet," plus 10 chorines (the "Charlie Glenn Beauties"). This band would remain in place until January 18, 1945 (when Young and Glenn squabbled in front of the Local 208 Board over Young's attempt to upgrade the band with musicians like Hobart Dotson on lead trumpet and Oliver Coleman on drums; Young did not obtain their services nearly so promptly as Glenn would have liked, so Glenn let the band go).

Walker's 1944 performances at the Rhumboogie had the same kind of impact as his earlier runs, and his stay was repeatedly extended (a new 5-week contract posted with Local 208 on September 7). The August 5 Chicago Defender reported, "Charlie Glenn brought T-Bone to Chicago at tremendous cost but the gamble is paying in sweet dividends. Nightly the place is packed with lines extending to the front door as many as three nights a week." Since Glenn had complained to Local 208 on June 1 that the cabaret tax, bad weather, and an unruly band that played too loudly were pushing him into the loss column, T-Bone's stand at the club must have been a tonic to the finances. T-Bone Walker completed his run at the Rhumboogie at the end of October, and on November 2, Wynonie Harris became the new headliner.

Until now, discographers have been under the impression that Charlie Glenn did not start his Rhumboogie label until May 1945. However, research into the Board minutes of Musicians Union Local 208 (now in the music collection at the Chicago Public Library) reveals that the first session for the new company took place on October 10, 1944. The first release was delayed for several months on account of squabbling between Charlie Glenn and Marl Young.

Near the end of Walker's third run at the Rhumboogie, Glenn decided start up a label as a promotional tie-in for his club. He saw a major opportunity because T-Bone Walker's immense popularity at the Rhumboogie and at clubs in Los Angeles had not yet translated into recordings; just the two sides for Capitol had featured him and his electric guitar.

The first session for the new company took place on October 10, 1944. For the records, Glenn asked Marl Young to pare down the 12-man house ensemble to 8 pieces and to write custom arrangements for the smaller unit. By 1943, Young, who wrote arrangements for the floor show at the Club DeLisa, had become tight with drummer Red Saunders and some of the members of his band. In fact, Young and members of the Rhumboogie house band often participated in the Monday morning breakfast dances at the DeLisa. Our best information puts Red Saunders and some other members of his band on the second T-Bone Walker session; given the closely similar sound of the band on the first one, we're assuming that they were there as well. Meanwhile, there is no sign of Eddie Johnson, who was a featured soloist at the Rhumboogie. Although the tenor sax solos on the both sessions are in the Coleman Hawkins mode, they appear to be the work of Moses Gant, who had previously served in the Milt Larkin band.

Discographies have always suggested that the first session took place "around May 1945," which coincides with the beginning of T-Bone's last appearance at the Rhumboogie. In a story in the November 17 Billboard, the label was said to have been started "some six months ago"—this must be where the May date in discographies probably originated. (The Mosaic box set of T-Bone's early recordings gives the date as c. May 1945, and the booklet places the session in Los Angeles, although the discographical leaflets for the CDs correct the location to Chicago.) Our source for the earlier date is the minutes of the Local 208 Board meeting of August 2, 1945. According to the minutes:

Mr. Charles Glenn of the Rhumboogie Recording Company, and members Marl Young and T-Bone Walker appeared before the Board as ordered, on the complaint of Mr. Glenn that member Young had failed to deliver arrangements and lead sheets to the several numbers recorded for him last October 10, 1944. Glenn further stated that he wrote to Young on February 1, 1945 asking for the arrangements and lead sheets, and later gave him the test records to use for taking off the leads. Glenn stated he learned later that Young had copyrighted the numbers in question.

Charlie Glenn said he had written the words to "Sail On Boogie" (Walker corroborated him on this) and declared that Young had "double-crossed" him and Walker. Walker acknowledged that "he agreed to cut Young in on T-Bone Blues No. 2 [i.e., Mean Old World], because Young did write the music for the tune."

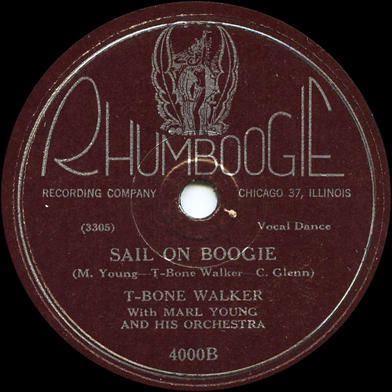

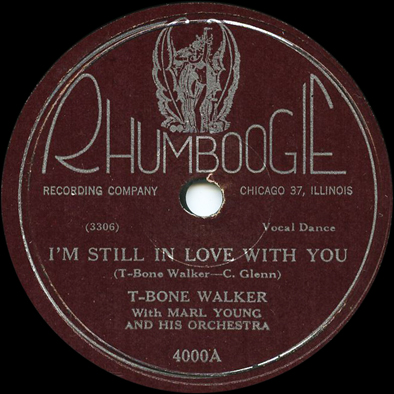

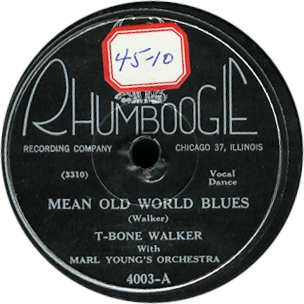

We can see that Young, who was studying law in 1945 and 1946, knew all about the importance of copyrights and didn't want Glenn grabbing up the composer credit. He and Glenn obviously did not trust each other, especially not after January 1945, when decided not to extend the Young band's contract. Four numbers from the first session are mentioned by name in the Board minutes: "T-Bone Boogie" (copyrighted May 31, 1945); "You Don't Love Me Blues" (May 31, 1945); "Sail On Boogie" (April 4, 1945); and "T-Bone Blues No. 2" (title changed by Young to the more memorable "Mean Old World Blues"; the copyright date on that one was August 1, 1945 because Young had to correct his original submission). "I'm Still in Love with You" and "Evening" (which was not written by any of the disputants, and carried no composer credit when issued) are from the same session.

The Young-Glenn dispute spilled over into the August 16 Board meeting. Glenn showed that he had paid Young $150 for the arrangements on December 23, 1944. Glenn already thought like a record company owner:

Mr. Glenn pointed out that Sail On Boogie had been used in the show at the Rhumboogie Cafe and that he paid Young $150.00 for recording arrangements and this sum was also in payment for the music to same. He stated that he would not have invested his money in recording same without owning this number, and that he could produced cancelled checks to substantiate his contention of ownership.

Glenn wanted the numbers copyrighted in his name. Apparently, anything involving the Rhumboogie Café was a major deal for Local 208; the Board did not announce a decision on the matter at the August 16th meeting, but the composer credits on the labels indicate that Glenn got his way. And Rhumboogie was finally able to release its first single.

Aaron Thibeaux "T-Bone" Walker (eg, voc); Marl Young (p, dir, arr); Henderson Smith (tp); Nick Cooper (tp); Nat Jones (as); Frank Derrick (as); Moses Gant (ts); Micky Simms (b); Theodore "Red" Saunders (d).

RCA Victor Studio, Chicago, October 10, 1944

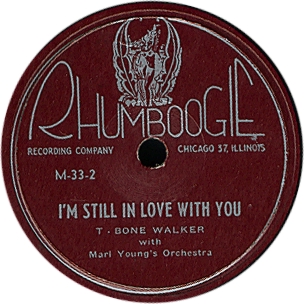

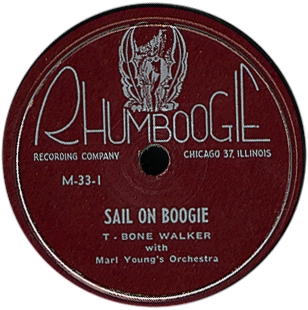

| QB-3305-1B | Sail On Boogie (Young-Walker-Glenn) | Rhumboogie 4000B, Rhumboogie M-33-1^, Blues Boy BB 304, Mosaic MR9-130, Mosaic MD6-130 [CD], Indigo IGO CD 2123, History 20.1948-H [CD], Classics 5007 [CD] | |

| QB-3306-1A | I'm Still in Love with You (Walker-Glenn) | Rhumboogie 4000A, Rhumboogie M-33-2^, Blues Boy BB 304, Mosaic MR9-130, Mosaic MD6-130 [CD], Rhino R2 79894 [CD], Indigo IGO CD 2123, History 20.1948-H [CD], Classics 5007 [CD] | |

| QB-3307 | unidentified title | ||

| (QB) 3308-2 | You Don't Love Me Blues (Walker)^ | Rhumboogie 4003-B, Blues Boy BB 304, Mosaic MR9-130, Mosaic MD6-130 [CD], Indigo IGO CD 2123, History 20.1948-H [CD], Classics 5007 [CD] | |

| (QB) 3309-1 | T-Bone Boogie (Walker-Glenn) [ens voc] | Rhumboogie 4002 B, Blues Boy BB 304, Mosaic MR9-130, Mosaic MD6-130 [CD], Indigo IGO CD 2123, History 20.1948-H [CD], Classics 5007 [CD] | |

| (QB) 3310-1 | Mean Old World Blues (Walker)^ | Rhumboogie 4003-A, Blues Boy BB 304, Mosaic MR9-130, Mosaic MD6-130 [CD], Rhino R2 79894 [CD], Indigo IGO CD 2123, History 20.1948-H [CD], Classics 5007 [CD] | |

| (QB) 3311-2 | Evening (composer not listed) | Rhumboogie 4002 A, Blues Boy BB 304, Mosaic MR9-130, Mosaic MD6-130 [CD], Rhino R2 79894 [CD], Indigo IGO CD 2123, History 20.1948-H [CD], Classics 5007 [CD] | |

| QB-3312-1 | Cherry Red Blues | RCA Victor test pressing |

The matrix series suggests that eight sides were recorded at this session and two were not used. We used to think that the the QB prefix pointed to Quality Recording, a studio at 206 South Wabash in the Loop. Run by Milton G. Wolf, Quality Recording was listed in the Chicago phone book in 1945 and 1946. However, QB could also be part of an incomplete RCA Victor matrix number (in full, D4-QB for 1944 or D5-QB for 1945). The recent discovery (by Saul Smaizys, email communication, August 23, 2016) of a one-sided RCA Victor test pressing of QB-3312 settles the matter.

Before he became the house bandleader at the Rhumboogie, Marl Young had written arrangements for the floor show at the Club De Lisa. In the process, he had become tight with Red Saunders and some of the members of his band from the Club DeLisa, where Young and members of the Rhumboogie house band often played the Monday morning breakfast dances. In any case, the recording band is not the same one that Marl Young fronted at the club; it is smaller, there is no sign of Eddie Johnson, who was a featured soloist at the Rhumboogie, and Young made custom arrangements for the recording session.

A trade ad from November 17, 1945 has it that "Sail On Boogie" and "I'm Still in Love with You" were paired for release on Rhumboogie 4001. But all extant copies of the 78 are numbered 4000, and the release is listed that way in Blues Research No. 3. Blues Research claimed to derive its release numbers from an undated distributor sheet put out by Record Distributors (839 South Wabash), which listed the three Rhumboogie singles among a series of "Latest Mercury Releases."

A trade ad from November 17, 1945 has it that "Sail On Boogie" and "I'm Still in Love with You" were paired for release on Rhumboogie 4001. But all extant copies of the 78 are numbered 4000, and the release is listed that way in Blues Research No. 3. Blues Research claimed to derive its release numbers from an undated distributor sheet put out by Record Distributors (839 South Wabash), which listed the three Rhumboogie singles among a series of "Latest Mercury Releases."

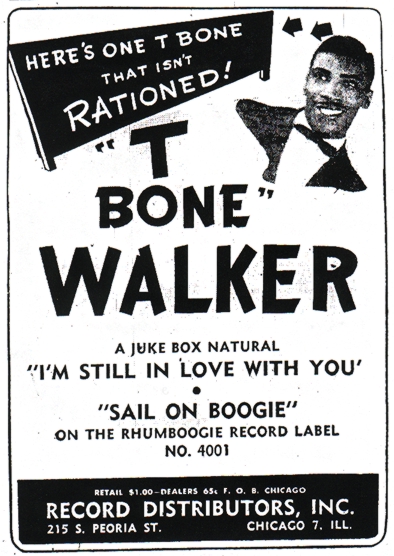

A good guess is that Rhumboogie 4000 came out in August 1945, since the Musicians Union heard the Charlie Glenn-Marl Young dispute on August 2 and 16 (and Glenn's name does show up in the composer credits on the records). By November the 78 had reportedly sold 50,000 copies. Its success forced Glenn to rethink the nature of his Rhumboogie label; the company had turned into something bigger than a promotional adjunct to his club. A story in Billboard, "Click Disk Spurs Rhumboogie Into Natl. Distribbing," (November 17, 1945, p. 20) announced that he would be pressing up 150,000 more copies of the first single and expanding distribution for the national market. As to who was doing the distributing (or the pressing), the article remained discreet. But an ad for Mercury Records, avaialble from Record Distributors, Inc, at 839 South Wabash in Chicago, appeared on the same page.

Rhumboogie 4000 was reissued, on the same brown Rhumboogie label, as Rhumboogie M-33 (same tunes, side designations reversed). Since Rhumboogie 4000 was pressed exclusively on the still-customary shellac and ground limestone, and some copies of M-33 were pressed on vinyl, our surmise is that M-33 was from 1948 or 1949, when Mercury was experimenting with plastic.

The November 17, 1945 story also announced the release that week of the second disk, "Evenin'" and "T-Bone Boogie" (Rhumboogie 4002) and the signing of another recording artist, Boogie-Woogie Allen, described as "another Chi blues singer." Glenn said "that he's expecting to ink some big Negro bands and other artists." Andrew Jackson "Boogie Woogie" Allen, a singer and pianist, was active in the Chicago clubs in November 1945. He shows up in the archives of Chicago's Musicians Union Local 208 on November 1, 1945, when he filed an indefinite contract with the Garrick Stage Bar. During 1946, Allen worked steadily at such establishments as the Taboo Lounge (April), the Winkin' Pup (May-June), Club Habana (July-August), and the Nameless Cafeacute; (September-December). In fact, he continued to be a regular on the Chicago scene through 1949. His only recording for Rhumboogie, however, was as a sideman on the Charles Gray session (which would be the only non-T-Bone Rhumboogie to see release). Nothing happened with big bands or other artists.

The same issue of Billboard featured a quarter-page ad promoting the single, but it was Record Distributors, Inc (address given as 215 South Peoria Street) that took out the ad. The ad proclaimed, "Here's one T-Bone that Isn't Rationed!".

Rhumboogie, then, was getting caught up in the fast-rising Mercury operation, which was founded in October of 1945. The two addresses for Record Distributors indicate that it was Mercury's own distribution branch; it so happened that Mercury's headquarters was at one address and its pressing plant was at the other (see ARLD). A release sheet from the same distributor that has been preserved shows a Mercury address that postdates July 1946, and lists Mercury products along with some indie lines that the distributor also picked up. In interspersing Rhumboogies among the Mercury releases, Mercury was acting as though it owned Rhumboogie.

Given the late release of Rhumboogie 4002 it seems likely that Rhumboogie 4003 was put out in early 1946. It probably postdated 5001, which still sports the familiar maroon-brown label. On 4003, the label is black but the graphics are the same, including the Charlie Glenn beauty in elaborate costume that served as Rhumboogie's logo.

Blues Boy BB 304 was a Swedish T-Bone Walker LP titled The Inventor of the Electric Guitar Blues. Mosaic MR9-130 (LP) and MD6-130 (CD) is a boxed set, released in 1990 under the title The Complete Recordings of T-Bone Walker 1940-1954. Rhino R2 79894, Blues Masters: The Very Best of T-Bone Walker, is a 2000 issue, as is Indigo IGO CD 2123, T-Bone Blues. The Indigo series appears to consist of bootlegs and has an uncertain country of origin. Classics 5007, T-Bone Walker 1929-1946, is a French reissue from 2001.

The matrix numbers and release information are largely drawn from the Mosaic booklet. No personnel are given by Mosaic, except for Walker and Young. However, the lineup is identical to that of the December 19, 1945 session as described in the booklet to the Mercury Blues 'n' Rhythm box: two trumpets, three saxes (two altos and a tenor), and rhythm. The altoists do not solo on the October 1944 tracks, but the tenor soloist sounds the same on both sessions.

T-Bone Walker was fully formed as a guitarist and a singer by the time he recorded his Rhumboogies. But those who expect an R&B combo sound on his them will be disappointed. It's easy to forget that T-Bone was making his bread appearing nightly with show bands: the Milt Larkin aggregation that backed him on his first run at the Rhumboogie ran to 14 or 15 pieces when fully staffed; the Dream Band and its successor under Marl Young's leadership were just a touch smaller, at 3 trumpets and 4 saxes. Left to his own devices, Young admired Art Tatum and Earl Hines, and played in a late Swing style (something like Clyde Hart's or Kenny Kersey's). But the dominant influence on this session belongs to Count Basie. It's there when the trumpets or the saxes work together on the uptempo numbers; it's in Young's piano accompaniment; it's in Moses Gant's tenor sax solos on "Sail On Boogie" and "T-Bone Boogie," jumping out of the ensemble in the manner already established by Herschel Evans and Buddy Tate. Red Saunders' drumming, however, is heavier and showier than anything Jo Jones would have been involved with.

T-Bone introduced most of this repertoire to the Rhumboogie with the Milt Larkin band, which was out of Houston, Texas. We doubt that Marl Young was eager to tamper with a winning approach. In fact "T-Bone Boogie" and "Evening" are the very same numbers that Jimmy Rushing sang on the first Count Basie small group recording, back in 1936 (the "Jones-Smith Incorporated" record used the generic title "Boogie Woogie"). Not that the comparison hurts T-Bone in the slightest; he takes the boogie notably faster than Rushing, and he has his own way of phrasing on "Evening" that owes nothing to the older version. "Mean Old World" (already one of T-Bone's signature tunes) and "You Don't Love Me Blues" are given raptly hushed accompaniment by Young's forces; Young's late-Swing tendencies surface occasionally in the wind-section chords that hang like gray clouds. (Young told Dan Kochakian that "Mean Old World" was his favorite from this session.) On "Evening," Henderson Smith's muted trumpet commentaries behind the vocals help to evoke the nostalgia that Helen Oakley Dance so masterfully described.

The previously unknown QB-3312 is a rendition of "Cherry Red Blues" (the only information on the label is the title). When the session took place, the song was still selling for the Cootie Williams band with Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson doing the vocal honors. The April 1944 release on Hit 7084 was on Billboard's Harlem Hit Parade by May 27, 1944 (p. 18) and would be going strong through January 1945. In the end we surmise that Charlie Glenn decided he would just as soon not try to compete with the Hit release. Especially not when Vinson began leading his own band, and Glenn booked it into the Rhumboogie (see below).

Despite the delay in getting the 78s out, Glenn wanted T-Bone Walker back at this club early the following year. Because of a curfew in force in Chicago through the early months of 1945, he didn't want to book Walker when he could not schedule enough shows per evening. Consequently, after deciding not to renew his contract with Marl Young's band, he settled for the Jeter-Pillars Orchestra from Saint Louis's famed Plantation Cafe, which came in on January 25 (Hillard Brown's band filled in Monday nights). Glenn put off bringing his star back till May 12, anticipating that as the war in Europe wound down the curfew would be lifted in 2 weeks. He brought in the Fletcher Henderson Band to anchor the show.

T-Bone Walker's return was indeed a triumphant one. Glenn launched it with an outdoor rally in the Chicago Loop, at State and Madison, part of a series of bond shows to raise money for the war effort. The Defender exclaimed, "never has the world's busiest corner appeared more groovy than during the one hour and fifteen minutes T-Bone and Henderson displayed their talents for bond purchasers." Henderson's band played new arrangements of "Born Happy" and "In the Mood" for the occasion.

A few days later it was show time. The Defender gushed, "The greatest floor show in Rhumboogie, the largest crowds to attend a nightery in local history, are but a few of the 'firsts' being offered at Charlie Glenn's emporium of fun, 343 Garfield Boulevard this week." The paper continued: "Topmost of the entertainment you'd expect, rests on the vocal chords and the guitar fingers of T-Bone Walker who is even better now than when last appearing here. T-Bone has added a number of new 'blue' tunes to his large collection and with the old ones being encored all over the place things are jumping."

The revue featured a comedian (Snooky Marsh), another singer (Bobbie Caston), a dancer (Mildred Whilow), plus some leggy chorines and a full band, the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra. According to Walter C. Allen's monumental monograph Hendersonia, Fletcher's band at this time included Elisha Hanna, Matthew Rucker, Willie Wells, and Lee Trammell, trumpets; Joe Brown and William "Geechie" Robinson, trombones; Edmund Gregory [later known as Sahib Shihab] and Emerson Harper, alto saxes; Woodrow Key and Otis Finch, tenor saxes; Grover Lofton, baritone sax; Vivian Glasby, piano; Bill Brookins, bass; Al Williams, drums; and George Floyd, ballad vocals (p. 435). With the the exceptions of Grover Lofton, Bill Brookins, and Al Williams, the musicians had all been traveling with Fletcher Henderson for some time (most had joined him in Detroit in January 1945). Vivian Glasby was from St. Louis and was new to the band (Fletcher at this point in his career preferred conducting to piano playing). At the time Henderson relied on Willie Wells, Geechie Robinson, and Woodrow Key and Otis Finch to do the jazz soloing (pp. 436-437). Former bandleader Willie Bryant was the MC.

There were changes in the revue line-up during the Walker's lengthy stay, though, beginning with the departure to California of the Henderson Orchestra after the shows on August 9 and their replacement by Walter Dyett and His Swing Orchestra. The dance act, the Rimmer Sisters, and singers Mabel Hunter and Delores Parker (a local girl out of Englewood High) became new members of the revue.

T-Bone's run ended in early September, when he was replaced as headliner by comedienne Moms Mabley. In October, Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson's band pulled in for a 6-week stay (contract accepted and filed by Local 208 on October 18). Vinson was followed by Eddie Mallory (5 week contract filed on December 6) and Eddie Cole (4 week contract filed December 20). At the time of T-Bone's departure, his first Rhumboogie single had been out for a month or less, but as sales began to mount, Glenn decided to bring T-Bone back to town for a follow-up session rather than a lengthy engagement at the club. At the time, Glenn had no idea that this would be the last time that T-Bone Walker worked for him.

T-Bone Walker (el-g, voc); Marl Young (p, dir, arr, bg voc); Melvin Moore (tp, bg voc); Nick Cooper (tp, bg voc); Nat Jones (as); Frank Derrick (as); Moses Gant (ts); Micky Simms (b); Red Saunders (d).

Chicago, December 19, 1945

| 409-2, 1036-SW, IM-493 | My Baby Left Me (Walker-Glenn) | Mercury 8016-A, Old Swing-Master 11A^, Imperial 1561451, Mosaic MR9-130, Mosaic MD9-130 (CD), Polygram 528292 [CD], Indigo IGO CD 2123, History 20.1948-H [CD], Classics 5007 [CD] | |

| 410-2, IM-494 | Come Back to Me Baby (Walker-Glenn) | Mercury 8016-B, Constellation CS-6, Imperial 1561451, Mosaic MR9-130, Mosaic MD9-130 (CD), Polygram 528292 [CD], Indigo IGO CD 2123, History 20.1948-H [CD], Classics 5007 [CD] | |

| IM-495 | I Can't Stand Being away from You (Walker) | Constellation CS-6, Imperial 1561451, Mosaic MR9-130, Mosaic MD9-130 [CD], History 20.1948-H [CD], Classics 5007 [CD] | |

| 411, 1040-SW, IM-496 | She Is Going to Ruin Me [Fast Woman*] (Walker) [ens voc] | Old Swing-Master 11B^, Constellation CS-6, Imperial 1561451*, Mosaic MR9-130, Mosaic MD9-130 (CD), Polygram 528292 [CD], Indigo IGO CD 2123, History 20.1948-H [CD], Classics 5007 [CD] |

T-Bone Walker came back to Chicago to make these sides after the commercial success of Rhumboogie 4000 and his follow-up release on 4002. They were of course done for Rhumboogie; otherwise there was no earthly reason for Charlie Glenn to be listed as co-composer on any of them. (We can see, too, that Marl Young had been duly chastised after the August 1945 dispute; his name is conspicuously absent from the credits.) But the tracks have traveled a tortuous path since then; various enterprising persons have managed to sell 300 or 400 percent of them.

The Rhumboogie matrix numbers are probably irretrievable. We'd thought QB-3307 and QB-3312 might have been remade at this session, but the discovery of a test pressing from October 10, 1944, numbered QB-3312, that was not recut here ("Cherry Red Blues") rules out the remake hypothesis. We have lost the original matrix numbers for all four of these sides.

The exact relationship between Rhumboogie and Mercury is unknown to us now, and it confused the trade papers back in 1946. Mercury 8016 was announced as a new release in Billboard on August 31, 1946 (p. 30). Two weeks later, Billboard ("Black & White Signs Phil Moore & T-Bone," September 14, 1946, p. 16) announced that T-Bone had signed, at $1500 for four sides plus royalties, with Paul Reiner and Ralph Bass's Black & White Records ("Three other diskeries were pitching for Walker"). There was a veiled reference to the December session, "Walker has apparently been tied in with Mercury Records, the details of which arrangement, however are not straight, altho it is thought that Mercury took over Rhumboogie masters, and [Walker's personal manager Harold] Oxley may threaten suit unless Mercury ceases issuing sides." (Oxley would threaten another suit against the Old Swing-Master label, when it picked this material up in 1949.)

The personnel and precise date for this session come from the booklet to the Mercury Blues 'n' Rhythm box (Polygram 528292). Marl Young would use many of the same musicians in the fall of 1946 when he launched his own Sunbeam label.

Matrix numbers 409-2 and 410-2, in Mercury's main series, are visible in the wax of Mercury 8016, which was listed among advance releases in Billboard on August 31, 1946 (p. 31). We got 411 from the Mercury Blues 'n' Rhythm booklet; we don't know whether "I Can't Stand Being Away from You" was given a matrix number by Mercury.

When Egmont Sonderling started Old Swing-Master in January 1949, with DJ Al Benson as his front man, one of the two apparently had obtained the now dormant material from this session. They released two sides in March 1949 on Old Swing-Master 11, a 78-rpm single. The 1000-series matrix numbers (with SW suffix) were attached by Old Swing-Master.

After Sonderling decided to phase out his record businesses, Old Swing-Master closed in June 1950. Around this same time, Sonderling may have sold the sides to Imperial, which had T-Bone under contract. Imperial slapped on matrix numbers in its own series. According to the Mosaic box, these were IM-453 through 456. However Michel Ruppli's discography The Aladdin/Imperial Labels assigns IM-493 through 496 to this session, while 453 and 454 go to Smiley Lewis and 455 and 456 to Tommy Ridgley (thanks to Claude van Raefelgem for catching the discrepancy; McGrath's R&B Indies confirms that 454, 455, and 456 appeared on releases by these artists). On a 1985 LP of Imperial blues material put out by French EMI, the date for the second Rhumboogie session is given as September 22, 1952, the location is given as "Hollywood?"—and no personnel are mentioned! Following the sequence of the Imperial master number system, September 22, 1952 appears to be when the Imperial master numbers were assigned. If the actual sale to Imperial took place in September 1952, it was virtually simultaneous with the sale to the Chance label! Imperial never released any of the sides, but after many mergers and acquisitions, they did appear on the EMI compilation. In 1990, the sides wound up in a Mosaic box mostly derived from material controlled by EMI.

Meanwhile, Al Benson (in all probability) during the interregnum between his Old Swing-Master association and the opening of his Parrot label, sold the masters to Art Sheridan of Chance Records. We know that he unloaded other masters to Chance during this period. (According to the late Marcel Chauvard, they were duly listed in the Chance company files, though Chance never released them.) A decade later, Ewart Abner Jr. (of Chance and Vee-Jay fame; he had just been kicked out of Vee-Jay in a management battle) and Art Sheridan (one-time owner of Chance) started a company called Constellation. It put out a series of LPs consisting of mostly Chance material. CS-6 was a various-artists blues collection, titled A Bucket Of Blues Vol. VI, that was released in 1964. The other tracks were by John Lee Hooker, J. B. Lenoir, and Sunnyland Slim (all of which came from the Chance archives, though the Hooker had also been purchased).

"I Can't Stand Being away from You" was issued for the first time on this LP. Most likely, it was passed over for release in the 1940s because the second half of the piece is a band arrangement that puts less emphasis on T-Bone's vocals and guitar than its session-mates do. Constellation misspelled another title as "She's Gonna Rain Me."

Imperial 1561451 was an EMI LP issued in France in 1985 under the title Hot Leftovers. Mosaic MR9-130 (LP) and MD6-130 (CD) is a boxed set, released in 1990 under the title The Complete Recordings of T-Bone Walker 1940-1954. Polygram 528292 is an 8-CD box set title Mercury Blues 'n' Rhythm Story 1945-1955, released in 1996. Indigo IGO CD 2123, T-Bone Blues is a bootleg release from 2000 with an uncertain country of origin. History 20.1948-H is a CD titled T. Bone Walker/Peter Chatman: This Life I'm Living. It was released sometime after 1998, which under European copyright law makes it a legal recording. History is a Hamburg, Germany-based label. Classics 5007, T-Bone Walker 1929-1946, is a French reissue from 2001.

We drew this release history mostly from the Mosaic box. However, Mosaic, following previous discographies, gives only "1945-1946" for the date and states that the band is the same group of unknowns as on the Rhumboogie session. (It does sound like the same lineup as before, though the recording quality is much better on this session than on the poorly-pressed Rhumboogie 78s that are the only remnant of the previous one. From the recently discovered test pressing of "Cherry Red Blues," it appears that the whole October 10, 1944 session was cut at a rather low level to begin with. In particular, Micky Simms and Red Saunders are more clearly heard on the December 19, 1945 sides.) Date and personnel from the Mercury Blues 'n' Rhythm box, which also supplies the Mercury matrix number 411 for "She Is Going to Ruin Me"; the Mercury annotators give Nat Jones' first name as "Nathan."

These four sides didn't deserve their checkered history. The recording quality is significantly improved on the second session: the band is less recessed and there is better detail everywhere, particularly from the piano, bass, and drums. At least some of the numbers were new, and Marl Young was no longer working the Rhumboogie or appealing to clubgoers' memories of the Milt Larkin band. Charlie Parker might have been a disruptive force on the bandstand, but Young had been listening to him carefully. The trumpet soloing is now in the hands of a young modernist named Melvin Moore. The punch in Young’s accompaniments may trace back to Earl Hines, but he owes the harmonies to more recent inspirations. On the slow "My Baby Left Me," bop riffing alternates with the usual R&B figures. On the fast "Come Back to Me Baby" Young sounds like Sadik Hakim (check out his accompaniment to Nat Jones' alto solo) and the closing ensemble verges on bop. On "I Can’t Stand to Be Away from You" Young’s spiky solos could pass for early Thelonious Monk (particularly the second interlude); he urges on bop solos by Melvin Moore and Frank Derrick with dissonant comping. Moses Gant's tenor solo pulls the easy-loping "She Is Going to Ruin Me" back to Swing, but check out the coda. None of this roiling modernism fazes T-Bone, who is in excellent form throughout.

The last Rhumboogie issue that we know of was nominally the work of Swing trumpeter Charles Gray. Born on September 7, 1918, Charles Gray was the son of Harry Gray, who ran Local 208; he had worked in Swing bands led by Eddie Cole and Carroll Dickerson as well as Nat "King" Cole (back in 1934) The date's raison d'être was gutbucket saxophonist and singer Joseph "Buster" Bennett (each side of the original release is billed as a "Blues Vocal"). Buster's name could not be used because he was under contract to Columbia at the time, and Gray and Charlie Glenn helped themselves to composer credit for two blues that, in their emphasis on extreme down-and-outness, are typical of Buster's repertoire.

The two "Charles Gray" sides very likely include the piano contribution of Boogie Woogie Allen; the keyboardist does a brief intro to each side but otherwise sticks with Boogie 101 comping patterns at medium tempo. Bennett was never a participant in the Rhumboogie revues; perhaps the session came about because Glenn saw more commercial potential in recording Boogie Woogie Allen as a member of Bennett's group, then a hot draw on the South Side, than in releasing solo piano recordings on him. At least Rhumboogie knew how to count—Columbia was in the habit of calling four and five-piece bands the Buster Bennett Trio!

Charles Gray (tp); Buster Bennett (voc, ts); Andrew Jackson "Boogie Woogie" Allen (p); Israel Crosby (b); unidentified (d).

RCA Victor Studio, Chicago, Jan. or Feb. 1946

| 3315-2 (1008-R) | I'm a Bum Again (Glenn-Gray) | Rhumboogie 5001-A, RST 91577 [CD] | |

| 3316-2 (1009-R) | Crazy Woman Blues (Glenn-Gray) | Rhumboogie 5001-B, RST 91577 [CD] |

Rhumboogie 5001 was a 78-rpm single released in 1946. Both sides were reissued in 1994 on RST 91577, an Austrian CD collection titled Chicago Jump Bands: Early R&B Vol. 1, 1945-1953. The liner notes by Frank Saturn correctly identify this as a Buster Bennett session, but incorrectly conclude that Charles Gray was Buster's alias.

While he no doubt appreciated the extra money, Buster may also have seen the Rhumboogie session as an opportunity to try out his tenor saxophone (previously he had recorded on alto and soprano only)

Charles Gray took over as lead trumpet player for the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra around September 1946. When Fletcher left the Club DeLisa on May 18, 1947 and Red Saunders returned, Gray was Red's lead trumpeter for at least the rest of the year. Gray also played trumpet on two Chicago recording sessions behind Big Joe Turner (for National, on November 29 and December 9, 1947). What we can hear of Charles Gray on the Big Joe sessions is consistent with the sound of the trumpet on these Rhumboogie items.

We infer that the pianist is Boogie Woogie Allen, given the similar lineup on the Columbia session of February 27, 1946, which also includes Charles Gray.

None of our sources identify the bass player and drummer, but they appear to be Buster's regulars from this period. (Later on, when Charles Gray recorded behind Joe Turner, the rest of the band consisted of Riley Hampton on alto sax, Otis Finch on tenor sax, Robert Moore on piano, Ike Perkins on electric guitar, Ellsworth [E. L.] Liggett on bass, and James Adams on drums—Hampton, Finch, and Adams were fellow alumni of the Henderson DeLisa band. Moore is definitely not the pianist on the Rhumboogie date. Whether Adams, who was from Chicago, could have recorded with Buster Bennett calls for more research.)

The RST reissue lists the matrix numbers as they appear in the wax (minus the take suffixes); the labels show 1008-R and 1009-R (as a copy in Tom Kelly's collection shows). The 3300 numbers appear to be from RCA Victor, as with the October 10, 1944 session. Presumably the prefix was D6-QB. Could the 1000 series numbers indicate another Mercury connection?

After the Charles Gray release, the Rhumboogie label just faded away. The operation was much too small to elicit much reporting from the trades. An item in the March 9, 1946 Billboard hints at a session of which we have no discographical record: "Charley Glenn cut 12 more sides for his Rhumboogie label by T-Bone Walker this week" (p. 22). All this means is that as late as March of 1946 Glenn was still telling people he had a record company. But we don't for a minute believe that the scavengers would miss any T-Bone masters cut at the height of his popularity. More than likely, Glenn was reporting on the 12 sides in his possession from the October 1944 and December 1945 sessions.

For now Rhumboogie had turned T-Bone Walker into a national star, and now other record companies were vying for his services. On September 14, 1946, Billboard reported the inking of the artist with Paul Reiner and Ralph Bass's Black & White label. Walker's personal manager, Harold Oxley (1897 - 1952), reported that Black & White would pay Walker a flat $1,500 price for four sides plus a three-cent royalty on each record and no breakage allowance. The sides Walker had recorded in December became masters of uncertain provenance.

Meanwhile, by the end of 1945, the Rhumboogie Club had already seen its best days. A raging fire on New Year's Eve, fortunately while the club was empty of patrons, practically destroyed the building. On February 18, 1946, the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra (with Marl Young at the piano bench for nearly all of the numbers) opened a few blocks away at the Club DeLisa, where it would remain till May 18, 1947. (Young would be replaced in August 1946 by a fellow from Alabama named Sonny Blount.) On March 23, Billboard announced that the club would be reopening with Dinah Washington and Eddie Mallory's Orchestra. When the Rhumboogie resumed business on April 3, 1946, there did not seem to be the same effort to maintain a top-line entertainment policy, and the booking of top acts was intermittent. In fact, the club probably could not afford to bring T-Bone Walker back for another run. Charlie Glenn liked the Nat Towles Orchestra—the only one that played softly enough, by his lights—enough to bring them back for 4 weeks starting in June (the contract was accepted and filed by the Local 208 Board on June 6).

By November of 1946, the Rhumboogie was shut down again, with rumors of new ownership in the air. These were confirmed when the Chicago Defender reported in its December 7 issue, "Joe Louis New Boss of Cafeacute; Rhumboogie." It said that Louis had become "sole owner," paying Charlie Glenn $12,000 for the club. Said the newspaper, "since the Café ...opened in 1942 the champ has been a rumored silent partner. Louis actually had advanced Glenn the money with which the business was started, a loan long since repaid, according to the former owner. A good-will arrangement kept the champ's brother, Pat Brooks, on the payroll." The club would be managed by Leonard Reed, reported by the paper to be a close friend of Louis. The pair had appeared as an entertainment act for two weeks at the Rhumboogie the previous year.

The Rhumboogie reopened on Christmas eve 1946, with two well-received shows, one starring Valaida Snow and the other other starring Deek Watson and the Brown Dots. Coleridge Davis and his Orchestra were the house band.

But a January 11, 1947 Defender ad suggested that all was not well with the Rhumboogie Club. The headline of the ad was not the name of the act, trumpeter and singer Valaida Snow, but "Looking for a Bargain?" The copy boasted of a 7 course dinner for $2.00, but included a boxed notice to the public, "Due to the prohibitive costs of the high type of entertainment we feel that you the public, both deserve and demand and which we feel it is our privilege and responsibilty to present to you, we cannot allow guests to bring in bottled wines and liquors." The Rhumboogie, indeed was presenting a "high type of entertainment." The revue format was still in place and the shows were still produced by Joe "Ziggy" Johnson. Name entertainment continued to be booked: Erskine Hawkins in late January and early February (Hawkins' contract with the club, now cited as Joe's Rhumboogie, was accepted and filed by Local 208 on January 16), followed by Johnny Moore's Blazers in March, and Sarah Vaughan in April and May.

As long as the club remained open, the record company was still officially in existence, though it had now been a year since the last recording session. The February 1, 1947 issue of Billboard still included Rhumboogie in its listing of indie labels, giving the club's address.

Meanwhile display ads for the club in the Defender were becoming ever more infrequent. For Vaughan's long run from March 27 through mid-May, there was only one ad, on April 19. The Vaughan stay began with the Slam Stewart Band, but by late April the band was the local Floyd Campbell Orchestra. Also on the bill was balladeer Johnny Hartman, along with the usual dancers and comedians. The April 26 Defender featured an item, probably drawn from a Rhumboogie promo, that said, "Sara Vaughan [sic], the number one chirper in Chicago this season, is still the main attraction on the Southside and her singing is keeping the Rhumboogie packed nightly." Further on it said, "The Rhumboogie has lowered its prices and as a result the spot is packed every night." The May 3 Defender announced that Vaughan was being held over.

But by mid-May Vaughan was playing the Sherman House in the Loop, and what of the Rhumboogie? Nothing but a one-line mention in the Defender's famed gossip column, "Everybody Goes When the Wagon Comes," which said "the Rhumboogie has closed on account of poor business."

Charles Walton got a more complete story from Floyd Campbell, who reported the club was indeed scuffling under the management of Leonard Reed and Pat Brooks. Campbell said, "Ziggy would pay us on Friday and tell us not to cash the check until Monday," with the hope that the weekend receipts would cover the bills. The bandleader also explained that the immediate failure of the club was not paying $10,000 in liquor taxes, whereupon the government padlocked the place. For the details of the club's last days, refer to Charles Walton's superb interview with Floyd Campbell (http://www.jazzinstituteofchicago.org).

T-Bone Walker, who personified the West Coast rhythm and blues explosion, effectively launched his solo recording career in Chicago, headlining at the Rhumboogie club and then making the Rhumboogie recordings. After Walker came a host of great vocalist/guitarists that he influenced, including B. B. King and Chuck Berry. Walker died March 16, 1975, in Los Angeles.

Marl Young, who backed T-Bone on the Rhumboogie sides, went on to start his own Sunbeam label in the Fall of 1946. Sunbeam fell through by the middle of 1947; Young unloaded his masters to Vitacoustic and left Chicago for Los Angeles in November 1947, expecting a long-term contract with Louis Jordan. Even though the gig fell through, he never looked back. He picked up work as an arranger immediately, and put together a successful piano trio. In September 1950 he was reunited with T-Bone Walker on a session for Imperial that included his tune "Too Lazy to Work." Young built a career in Hollywood, helping to integrate the Musicians Union locals, and eventually becoming the musical director of the Lucille Ball's Here's Lucy show.

Buster Bennett continued on the Chicago scene through the end of 1953, then apparently dropped out of music (he was erased from the Local 208 membership rolls for the final time in 1956). He died in complete obscurity in Houston, Texas, in 1980.

We've relied on the following sources for most of our historical and discographical information. Bill Dahl's profile on T-Bone Walker in the All Music Guide to the Blues (1999); Dempsey J. Travis's book An Autobiography of Black Jazz (1983), which devotes an entire chapter to the Rhumboogie Club; Helen Oakley Dance's Stormy Monday: The T-Bone Walker Story (1987), which likewise devotes an entire chapter to the Rhumboogie Club; and two volumes of that indispensable reference work, Blues Records 1943-1970 Volume One: A to K by Mike Leadbitter and Neal Slaven, and Blues Records 1943-1970 Volume Two: L to Z (1994), compiled by Mike Leadbitter, Leslie Fancourt, and Paul Pelletier. Walter C. Allen's Hendersonia: The Music of Fletcher Henderson and his Musicians (Highland Park, NJ: 1973) provides many details on the Fletcher Henderson band's stays at the Rhumboogie and the Club DeLisa. Dan Kochakian's May 2003 article "The Marl Young Story," Blues & Rhythm, 179, 16-20, provides further valuable details about Young's work at the club and on the recording sessions. Our thanks to the late Eric LeBlanc for dates on Harold Oxley.

Click here to return to Red Saunders Research Foundation page.