Revision note. With help from Marv Goldberg, we are updating and correcting our information on Kitty Stevenson, who recorded at least 8 sides for Vitacoustic around December 15, 1947; four of her sides ended up on Old Swing-Master. We will be cross-listing more Vitacoustic material that ended up with Old Swing-Master on the Vitacoustic page. We can at last supply information about three 78s by accordionist Joe Petrak, whose signing to Old Swing-Master was announced in Billboard on May 28, 1949. We have also learned where the interest in polka came from; Egmont Sonderling's final fling with the record business took place in 1955, when he joined a DJ who had been running polka programs on WOPA and started a label called Polka Artists. We have updated our photo files and added photos of Old Swing-Master 14, 24, and 25, among others.

Old Swing-Master was the first record company to involve the prominent DJ and occasional recording producer Al Benson (1908-1978). Al Benson, whose real name was Arthur Leaner, is profiled in greater depth on our Parrot/Blue Lake pages.

Contrary to what has been thought, Old Swing-Master was not intended as a vehicle for Al Benson's efforts as a record producer. Just two sessions were recorded under his direction: one by the Benson All Star Orchestra (which was released on Old Swing-Master 15 and 16), and one by the Four Shades of Rhythm (which led to Old Swing-Master 23). All of these sides were actually cut before Old Swing-Master opened. Old Swing-Master rose from the ashes of a Chicago-based company called Vitacoustic. While Vitacoustic made its splash in White pop music, scoring a huge hit with its first release by the Harmonicats, the company launched an ambitious "race" series in September 1947. Because the management of Vitacoustic had fallen out with Bill Putnam of Universal Recording, and studios were heavily booked during the last quarter of 1947, most of the "race" material was cut at United Broadcasting. After recording vigorously in October through December 1947, Vitacoutstic fell victim to overexpansion and overambition. The company declared bankruptcy in February 1948, at which time it owed United Broadcasting $13,800. Egmont Sonderling, the owner of United Broadcasting, refused to turn over sides that Vitacoustic hadn't paid him for recording, so they were not offered at auction when Vitacoustic was liquidated. Sonderling launched Old Swing-Master so he could recoup some of his losses by releasing material that Vitacoustic had recorded and mastered at his studio.

Old Swing-Master kept going by acquiring material from two small local labels (Marvel and Planet) that lacked enough capital to keep their wares in front of the public. Old Swing-Master also leased sides from the Jazz Ltd. label, a boutique operation run out of the club of the same name. There was further scavenging from the defunct Rhumboogie operation and from the Sunbeam label, whose remains had been acquired by Vitacoustic. Toward the end of its lifetime, the much more substantial Miracle operation ran into financial difficulties; its owner, Lee Egalnick, also owed Sonderling money; Egalnick unloaded masters by Memphis Slim, Sonny Thompson, and others, which Old Swing-Master put out in December 1949 and early 1950.

The only artist who was signed directly by Old Swing-Master was an accordion player named Joe Petrak. It's still possible that Petrak initially recorded some of his material at his own expense.

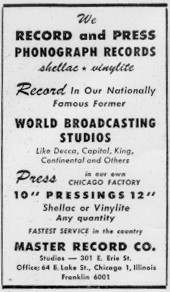

The founding of Old Swing-Master (shortened in the trade papers—and maybe on some labels—to Swing-Master or Swingmaster) was reported in Billboard on January 29, 1949 ("Swingmaster & Gong in Wax Sweepstakes," p. 40). The prime mover behind the label was Egmont Sonderling. Born in Germany on February 27, 1906, Sonderling came to the United States in 1923. He began a career in broadcasting as a radio announcer. In 1939, he opened United Broadcasting Studios at a location previously used by RCA Victor for recording. In 1945, he moved his studio operation to 64 East Lake. Toward the end of 1945, he entered the pressing business with Master Records; he ran an ad in Billboard on January 5, 1946, declaring that he was ready to take orders to press 2 million records for delivery that year. By 1947, United Broadcasting was drawing major business from independent labels in Chicago. At some point between June 1947 and March 1948 (judging from phone book listings), Sonderling bought the old World Broadcasting Studios at 301 East Erie and moved United Broadcasting there.

Sonderling was very much an accidental record company owner. He had held onto a pile of masters that the Vitacoustic company had recorded in his studios during the last quarter of 1947, plus some that had been recorded elsewhere but were entrusted to his operation for mastering and pressing. In October 1948 he refused to turn them over a receiver to be auctioned off with Vitacoustic's other assets, citing liens that he held over masters that he had not been paid for (Vitacoustic owed him $13,800). It didn't help that Bill Putnam, owner of Universal Recording, was the receiver, and that Universal was owed $16,000. For Sonderling to get any of his money back, he would have to issue and sell the material himself. He must have figured that bringing in the powerful local DJ Al Benson would give his records a head start in the market. The name, Benson's favorite moniker for himself, was designed to butter him up, and the equity he was probably given in the label was an obvious incentive as well. The general manager was reported to be Leonard Davis, who previously worked as purchasing manager for Mercury. The owners took pains to discount Benson's involvement ("Davis... denied that Benson was financially interested"). That Benson's role was made an issue in the story was telling.

Sonderling's idea was to run a record label by picking up the masters of defunct or tiny labels rather than spending hours in the recording studio, hiring studio time, paying engineers, paying arrangers, and signing recording artists. (Despite several years running a commercial recording studio, Sonderling hardly ever issued newly recorded material—he had no yen for this side of the business.) He thought that the connection with Benson was all he needed to run a successful label. It did not work out that way, as the company expired after less than a year and a half in business, with just 20 known releases under its belt.

The original address for Old Swing-Master was 154 East Erie Street, on the city's near North Side, just down the street from United Broadcasting Studios at 301 East Erie Street. By early 1949, 154 East Erie was the address of the subsidiary Master label as well. By July of 1950 the now moribund Old Swing-Master was located on the near South Side, at 2406-08 South LaSalle (this was the home of Chord Distributors, which would not be at that address much longer).

Upon its founding, Old Swing-Master reported that its first releases would be all be recovered from the Vitacoustic operation: sides by Kitty Stevenson, Howard McGhee's All-Stars, the Four Shades of Rhythm, and Christine Randol, "with others set by Miss Cornshucks, Johnny Bothwell, and Ed McAfee" (Billboard, January 29, 1949, p. 40). Vitacoustic was a Chicago-based label that had been active from March 1947 through February 1948. Initially all of its material (including its monster hit record, "Peg o' My Heart" by the Harmonicats) had been pop music aimed at white audiences. There was a split at the end of August 1947 between the label's owners, Lloyd Garrett and Jack Buckley, and Bill Putnam and George Tasker of Universal Recording, where the label had done its studio work and was physically housed. As a consequence of the split, Putnam's Universal label would be recording the Harmonicats in the future. Whether this was a cause or a consequence of the split, Vitacoustic decided to move into the "race" market (it also recorded at least three Country artists, though just two Country records actually saw release). Most of what Vitacoustic actually issued in its Jam Sesssion Series, R&B 78s with numbers starting at 1000, was either derived from the Detroit label Sensation or the product of a pact with Sensation. In the final quarter of the year, Vitacoustic recorded a pile of its own material (pop, Country, and R&B) in anticipation of the recording ban scheduled for January 1, 1948, then went under before it could release it.

The last releases in Vitacoustic's pop and race series appeared in February 1948; in its bankruptcy petition at the end of that month, Vitacoustic claimed that the cost of recording 400 masters in anticipation of "B-day" had gotten the label into massive debt. Because Vitacoustic had recorded its "race" series at United Broadcasting Studios, and hadn't paid Egmont Sonderling for his services before it started running out of money, he held onto the unissued masters. In October 1948, fearing that he would never get any of his money back, Sonderling refused to allow them to be auctioned off with the rest of Vitacoustic's assets. Some masters in the Vitacoustic Jam Session Series were clawed back by Bernie Besman of Sensation; for others, it appears Sonderling kept the master and Besman got a copy. (Sonderling had good reason to worry about the market for masters: Vitacoustic's pop material failed to attract serious bids when the auction took place in April 1949. Except for some items that Bill Putnam eventually transferred to Egmont Sonderling, very cheaply, essentially none of it found a home.)

The first four artists mentioned in the Billboard article had all indeed recorded for Vitacoustic. The Miss Cornshucks sides had been cut by Sunbeam, a small Chicago independent that operated from the fall of 1946 through summer of 1947. Vitacoustic had then struck a deal with Marl Young, the proprietor of Sunbeam, to reissue some or all of his material. The deal was made in September 1947, and Marl Young was even proclaimed a Vitacoustic artist in ad that ran in Billboard on January 3, 1948. But nothing of Sunbeam origin came out on Vitacoustic, which ran out of money too quickly. It appears Sonderling impounded some Sunbeam masters when Vitacoustic folded, while Young, who had closed Sunbeam up and moved to Los Angeles in November 1947, was not around to complain.

Ed McAfee was a member of the Four Shades, who had managed to get one release out on Vitacoustic; the reference was redundant.

Johnny Bothwell was a jazz alto saxophonist who had been one of the soloists in the Boyd Raeburn "modern" big band and had cut some sides with his own bands for the Signature label; he was featured in an advertisement for Vitacoustic's pop and country artists in Billboard on January 24, 1948 (Juke Box supplement, p. 75). It looks as though his sides were done at United Broadcasting and were retained by Sonderling along with the sides intended for the "race" series. Old Swing-Master never got around to using anything by Bothwell, and we don't know what happened to this material. (Howard McGhee recalled doing a session with someone else's big band for Vitacoustic, but couldn't recall the leader's name. As an ex-Raeburnite, Bothwell would have been motivated to get a prominent bop soloist onto his recording date. The fate of these sides is likewise unkown.)

The Old Swing-Master operation was controversial from the start. On March 26, 1949, Billboard, in a story by Johnny Sippel, "Chi Dealers Tackle Problems," reported on the formation of a trade organization of African-American record shops, and of its dispute with Al Benson. It was bad enough, from store owners' point of view, that Benson ran his own record shop at 40th and State, and frequently plugged it in on the air. Even worse, "Shop owners in the new org contend that Benson has a financial interest in Swingmaster label, a new Chi race label, and that he is overplugging his own disks to the detriment of other disks" (p. 44).

The Kitty Stevenson disk, "Blues by Myself," was promoted in the same issue of Billboard: "Gal intones an earthy, moody blues here. Drag orking gives a strong assist." The two Stevenson sides on Old Swing-Master 10 derived from her one and only session for Vitacoustic, around December 15, 1947. The Detroit Tribune ran a story on December 20, mentioning the singer's recent trip to Chicago with T. J. Fowler's band (she had been appearing with the band at Club Sensation in Detroit). The paper even identified, with surprising accuracy, 8 titles that she had recorded. Vitacoustic tagged Stevenson as a Jam Session Series artist but didn't succeed in releasing any of this material. The original title to "Blues by Myself" was "Sleeping by Yourself." A few copies of Old Swing-Master 10 circulated with this title on the A side, then the company decided it had better reprint the labels. Marv Goldberg has located a record store ad in the Indianapolis Recorder for February 12, 1949: one of the new releases listed is "Sleeping by Yourself—ßA Red Hot Number by Kitty Stevenson."

Accompaniment on the session was, for the most part, by a seven-piece band. We used to think it was led by Todd Rhodes, and others have thought similarly. This was all a mistaken inference from later appearances (and records) that Kitty Stevenson made with the Rhodes and his Toddlers. T. J. Fowler played piano. Emitt Slay is thought to have been the guitarist. Otherwise, the band consisted of trumpet, alto sax, tenor sax, bass, and drums. Fowler was known to favor that three-horn lineup, but the only personnel we have for such a band dates from one of his Sensation releases in 1950; we also have the lineup that recorded with him for States in 1952. There are two further sources of trouble. Stevenson recorded a blues titled "Evening Sun" with what sounds like the exact same Fowler band, and Bernie Besman of Sensation retained a master. We don't know whether Egmont Sonderling ever had a copy of it. Then there are three songs that (under mildly variant titles) were also recorded by Kitty Stevenson with a five-piece band (tenor sax, piano, electric guitar, bass, drums). Besman kept the masters on these; we don't know whether Sonderling did or not. What's worse, we have no idea why anyone wanted Kitty Stevenson to record the same songs in front of a different band, which, for all we know, was just T. J. Fowler's current ork without the trumpeter and the alto saxophonist. Having no clue where else these other four tracks belong, we've placed them with the 8 that we know were recorded for Vitacoustic.

Two further tracks from the same session for Vitacoustic were released on Old Swing-Master 20 (hence we've pushed them down the list). For some reason, the matrix numbers were altered; they should have been in the V1940s, as had been the case for Old Swing-Master 10. "Hold Them Joe" is an oddity in Kitty Stevenson's repertoire; not a blues, not a ballad, not R&B. The title should have been rendered "Hold 'im Joe," because Joe needed to hold onto one donkey. The song is from Jamaica, and was first recorded by a Calypso band from Trinidad in 1926. It's better known as "The Donkey Want Water." For this number only, one of T. J. Fowler's saxophonists switched to clarinet, the other saxophonist laid out, and the trumpeter put in a mute. Stevenson and the band seemed unsure whether the song was from an English-speaking island or a Spanish-speaking island, and the rhythm is closer to a rhumba than a Calypso. Kitty Stevenson claimed to have written it. When Harry Belafonte, who knew a Calypso from a rhumba, recorded the song (in 1954) he also claimed to have written it.

Also listed in the March 26 Billboard was the Christine Randol 78 (Old Swing-Master 12). This came from what we've learned was her second session for Vitacoustic, toward the end of December 1947. Accompaniment to her piano playing and singing was minimal: a string bass. There had been a first session for Vitacoustic around the beginning of the same month; nothing's ever emerged from it except Vitacoustic 1006. This 78 slipped out as Vitacoustic was filing for bankruptcy and is so rare that we first learned of its existence in 2020. There could have been quite different accompaniment on the early December session. Presumably Egmont Sonderling had the masters from it at his disposal, but he didn't use any of them for Old Swing-Master and there are no reports of Sonderling or Al Benson selling them to anyone else in later years.

In the April 2, 1949, Billboard,'s listing of the coming release of two T-Bone Walker sides—"Don't Give Me the Run Around" [sic—on the record the title was "She Is Going to Ruin Me," which T-Bone pronounced as "roon"] and "My Baby Left Me"—sparked a dispute with the West Coast label Black & White, which had the blues guitarist under exclusive contract. T-Bone's manager, Harold Oxley, sent a letter to a letter to Old Swing-Master demanding to know the origin of those recordings. (Since they had been cut back on December 19, 1945 for Rhumboogie, they were not in violation of T-Bone's contract with Black & White, signed in September 1946. No doubt this is what Sonderling and Benson wrote back to Oxley.) Old Swing-Master 11 was released without a hitch, though we have our doubts about the sales figures.

An April issue of Billboard supplied a review of "Reminiscing of You Dear," which featured Ethel Duncan on vocals and the Benson All Star Orchestra (Old Swing-Master 15). "Gal sings a mediocre ballad with fair feeling and phrasing," the reviewer concluded, "but little style or individuality." Old Swing-Master 16, with the other two sides from the session, which Al Benson had organized on a freelance basis in the flal of 1948, was probably released at the same time.

By May of 1949 Old Swing-Master, which still had a lot of Vitacoustic masters to choose from, was definitely looking for material from other sources. During that month, Billboard reported that Swing-Master had picked up six Jazz Ltd. masters that had been produced in Chicago by musician and club owner Bill Reinhardt. The article noted that Muggsy Spanier and Sidney Bechet were featured. Some coverage in Down Beat explains what was happening more clearly. In March 1949, Jazz Ltd. had put out an album of 4 Dixieland 78s in a limited edition of 1000. Intended strictly as a promotional device for Bill and Ruth Reinhardt's club, the album had sold out quickly. The Reinhardts realized there was additional demand for the individual 78s. On June 17, 1949, Down Beat announced that Jazz Ltd. was being "'Forced' into Disc Business." "The albums... will not be recut, although six of the eight sides will be issued as singles... Label, too, will be switched from [red on] silver to red and white." (The new labels came out more like maroon and gray.) The Down Beat item also specified that the Jazz Ltd. masters were not actually being acquired by Old Swing-Master: "Discs will sell for $1 and will be distributed by United Broadcasting Studios through Swingmaster distributors." See the Appendix for more about the Jazz Ltd. items, which ended up being reissued on Jazz Ltd. and other labels.

A review in May covered Old Swing-Master's reissue of Snooky & Moody's "Telephone Blues," which had been picked up from Planet. Planet was a tiny operation that Near North Side record shop owner Chester A. Scales probably had an interest in. In any event, Scales had recorded the sides. The Billboard reviewer was typically negative ("not especially inspired"), but the record was already a classic of postwar Chicago blues. Mike Rowe said of it, "It is the lilting swing imparted by Moody's guitar that makes the record sound so modern for the time. Equally rhythmic is Snooky's singing and the interplay of the voice, harmonica, and guitar is particularly exciting." November or December 1948 is the most likely recording date, given the blatant reference to John Lee Hooker's "Boogie Chillen" on the "Boogie" side, and the artists' recollections of the Old Swing-Master release coming out not long after the sides were recorded.

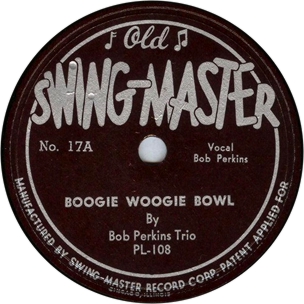

Another Planet-derived item by the Bob Perkins Trio was reviewed in Billboard on May 7, 1949 (our thanks to Bo Sandell for bringing this item to our attention). The Bob Perkins item was recorded later than the blues sides—between January and March of 1949, when he was playing an extended enagement at a club called the Music Bowl. (One of the titles is virtually a musical advertisement for the club.) It is possible that Chester Scales was not involved in recording Perkins, who was after all a jazz alto saxophonist with some ambitions in the Louis Jordan direction. A little later, Old Swing-Master would reissue two 78s that had come out on Planet's companion label, Marvel.

July 1949 found Billboard reviewing Old Swing-Master 23, "I Can Dream" by the Four Shades of Rhythm, which came from a freelance session they had done for Al Benson the previous year. Of course there was a comparison (favorable, in this case) to the vocal group the Orioles, who were taking the country by storm at the time. We suspect that two other sides were made at this session, but we have no idea what they were or what happened to them later.

In September 1949, Billboard reported that Old Swing-Master had obtained some Little Miss Cornshucks sides originally recorded in September and October 1946 for Sunbeam. It's possible Sonderling had had these in his possession all along, as there was no indication of Marl Young attempting to prevent reissues. Old Swing-Master now reissued, as Old Swing-Master 26, Miss Cornshucks' great hit record, "So Long." It happened so fast that the reissue was listed as a new release in Billboard, October 1, 1949, p. 31— two weeks after it had been reviewed.

Running a record company off the release of old masters was not a winning proposition for a lot of Old Swing-Master's releases. It was not a bad idea to re-release "So Long," which had enjoyed local popularity when it came out in the fall of 1946 on Sunbeam 104, but suffered from inadequate distribution. Besides, Ruth Brown had just covered the song on her first release for Atlantic (Cash Box, July 9, 1949, p. 13). In 1949, the blues ballad singer with the hick gingham dress and big bow in her hair was still wowing audiences in the major clubs across the nation, including the Club De Lisa in Chicago, where through a good part of 1949 she headlined various revues. The song she was still wowing them with was "So Long."

As too often happens with trade magazine reviewers, Billboard completely dropped the ball, slamming the record as "draggy" and "dull" and the sonics as "poorly balanced" (September 17, 1949, p. 111). Whatever its combined sales amounted to, "So Long" was one of the great songs that everyone talked about in the late 1940s.

Miss Cornshucks' national fame dissipated after she suffered a nervous breakdown in 1951 or 1952. But while maintaining a residency in Kenosha, Wisconsin, she continued through the decade to headline at the Club DeLisa, as well as Little Joe's High Hat Lounge, The Flame, the Crown Propeller Lounge, and Budland (with King Kolax in 1956). Her last major appearance, at Roberts Show Lounge in July 1960, produced a recording contract with Chess and an LP but led to few other gigs. On the LP she reprised "So Long," which the liner note writer referred to as a "tune nobody else could touch."

Also on September 17, 1949, Billboard (p. 111) ran a review of the Four Shades of Rhythm's "Don't Blame Me" (Old Swing-Master 33) This item was a Vitacoustic relic, recorded at the group's first Vitacoustic session in December 1947; the flip, "Yesterday," was from their second Vitacoustic session done just before the recording ban hit. We haven't heard of any Old Swing-Masters between 27 and 32 (up to this point the issue numbers had been consecutive, except for Old Swing-Master 21). Maybe the Four Shades got number 33 because of their previous releases on 13 and 23? In any event, 33 was the last in the original Old Swing-Master series, which was finished after 8 months.

An Old Swing-Master 1000 series started with three 78s by accordion player Joe Petrak. We used to think these might have been picked up from Miracle. Instead, this was a unique case of an artist being signed to the company. "Swingmaster has inked Joe Petrack [sic], solo accordionist, and has taken over a Menasha Skulnick [sic] master from the comedian, with an option to make more masters if the first is successful" (Billboard, May 28, 1949, p. 37).

We don't know of any release on the label by Menasha Skulnik, a Yiddish theater actor who was born in 1890. And if the first master was never released, we're not expecting to find follow-up sides. In 1947 Skulnik had made a bunch of commercial recordings of Yiddish songs and comedy bits in English, for a New York-based company called Banner (this was a new operation that specialized in Jewish, Irish, and Italian performers; it had no connection with the American Record Company's Banner label of the 1930s). He would make some spoken-word recordings in the 1950s and the 1960s. Anyone who has spotted a Skulnik on Old Swing-Master, be it derived from Banner or otherwise, please let us know.

For Joe Petrak, the known matrix numbers (which we got from Tom Kelly's copy of Old Swing-Master 1000) are UB9510 and UB9511. These belong to the infamously ambiguous 9000 series that United Broadcasting used for recordings made in 1948 (when nearly all were in violation of the second Petrillo recording ban) as well as in 1949 (when the recordings were OK with the Musicians Union again). In light of the Billboard announcement, we're inclined to read them as indicating a recording session in April or May 1949. Petrak ended up with releases on Old Swing-Master 1000, 1001, and 1002. From a dub of Old Swing-Master 1000 provided by Tom Kelly, we know that Petrak was recorded in a small group setting that included a trumpet player. Billboard reviewed Old Swing-Master 1000 on June 11, 1949 (p. 127). On December 17, 1949, Billboard announced 1001 (p. 88) and 1002 (p. 36) among its new releases; on December 24, Billboard (p. 32) carried reviews of both. That same week, Cash Box reviewed 1002 (December 24, 1949, p. 10).

We'd wondered where the interest in polka came from. Al Benson had no discernible attraction to the genre. Even if he'd had one, his shows on WGES were rather unlikely to reach buyers of polka records. However, several years after he closed Old Swing-Master, Egmont Sonderling would briefly be involved with a polka label.

By the end of 1949, Miracle was having trouble with distributors and was facing slumping sales on its new releases. The company owed Egmont Sonderling (whose studio and pressing plant Miracle used regularly). Label owner Lee Egalnick dealt some sides to Old Swing-Master, where they appeared in a new 1000 series. The December 24, 1949, issue of Billboard(p. 99) reviewed Old Swing-Master 1010, Memphis Slim's "Country Girl." Old Swing-Master 1011, a Sonny Thompson release derived from Miracle, probably also came out in December 1949.

On March 25, 1950, Billboard reported that Lee Egalnick of Miracle had sold 10 masters by Memphis Slim to Egmont Sonderling of the Swing-Master label (these may have been in addition to the earlier transaction). For the two releases that ensued on the Master label, we direct readers to our Miracle listing. Unfortunately, the sides on Master were given non-informative matrix numbers in an MS series). "While Slim is still with Miracle, the masters turned over to Sonderling were made with a quartet two years ago. Slim is now working with a different six-piece group" (p. 45). Master 1020 and 1030 followed the announcement of the Memphis Slim deal in March; they are not known to have Old Swing-Master incarnations.

The Old Swing-Master 10 series releases that we have seen used a dark red label with silver print (Old Swing-Master 17 is the lone exception, appearing on a black label). The Old Swing-Master 1000 series sported a dark blue label with the same logo.

| Matrix Number | Serial Number | Artist | Title | Recording Date | Release Date |

| [Vitacoustic] | (P-Vine Special [J] PLP 708) | Kitty Stevenson | Train No. 1 | c. December 15, 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Ace CDCHD 1087) | Kitty Stevenson | How Long, How Long, How Long | c. December 15, 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | (P-Vine Special [J] PLP 708) | Kitty Stevenson | Comes the Day | c. December 15, 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Ace CDCHD 1087) | Kitty Stevenson | Then Comes the Day | c. December 15, 1947 | |

| V1941Sw [Vitacoustic] | 10A | Kitty Stevenson | Sleeping by Yourself [first pressing] Blues by Myself |

c. December 15, 1947 | January 1949 March 1949 |

| V1943Sw [Vitacoustic] | 10B | Kitty Stevenson | I'm Satisfied | c. December 15, 1947 | January 1949 |

| [Vitacoustic] | (P-Vine Special [J] PLP 708) | Kitty Stevenson | That Jive | c. December 15, 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Ace CDCHD 1087) | Kitty Stevenson | How about That Jive | c. December 15, 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | unissued | Kitty Stevenson | Things Will Change Someday | c. December 15, 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Ace CDCHD 1087) | Kitty Stevenson | Evening Sun | c. December 15, 1947 | |

| 1040 (1040SW in wax) [Rhumboogie] |

11A | T-Bone Walker | My Baby Left Me | December 19, 1945 | March 1949 |

| 1036 (1036G-SW in wax) [Rhumboogie] |

11B | T-Bone Walker | She Is Going to Ruin Me | December 19, 1945 | March 1949 |

| V1957Sw [Vitacoustic] |

12A | Christine Randol | Goodie Goodie | late December 1947 | March 1949 |

| V1960Sw [Vitacoustic] |

12B | Christine Randol | Mood Indigo | late December 1947 | March 1949 |

| V1950Sw [Vitacoustic] |

13A | 4 Shades of Rhythm | Eddie McAfee, piano Oscar Pennington, guitar; Eddie Myers, bass; Oscar Lindsay, drums | My Blue Walk | late December 1947 | March 1949 |

| V1953Sw [Vitacoustic] |

13B | 4 Shades of Rhythm | Eddie McAfee, piano Oscar Pennington, guitar; Eddie Myers, bass; Oscar Lindsay, drums | Baby I'm Gone | late December 1947 | March 1949 |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Savoy MG 12026) | Howard McGhee Orchestra | Flip Lip | October 15 or November 10, 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Savoy MG 12026) | Howard McGhee Orchestra | Belle from Bunnycock | October 15 or November 10, 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Savoy SJL2219) | Howard McGhee Orchestra | Belle from Bunnycock [alt.] | October 15 or November 10, 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Savoy MG 12026) | Howard McGhee Orchestra | The Last Word | October 15 or November 10, 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Savoy MG 12026) | Howard McGhee Orchestra | The Man I Love | October 15 or November 10, 1947 | |

| V892 SW [Vitacoustic] |

14A | Howard McGhee Orchestra | Hot and Mellow [Yardbird Suite] |

late December 1947 | March 1949 |

| UB 9110SW [Vitacoustic] |

14B | Howard McGhee Orchestra | Messin' with Fire [Donna Lee] |

late December 1947 | March 1949 |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Savoy MG 12026) | Howard McGhee Orchestra | Merry Lee [Hackensack] |

late December 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Savoy MG 12026) | Howard McGhee Orchestra | Short Life | late December 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Savoy MG 12026) | Howard McGhee Orchestra | Talk of the Town | late December 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Savoy MG 12026) | Howard McGhee Orchestra | Bass C Jam [Byas a Drink] |

late December 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Savoy SJL2219) | Howard McGhee Orchestra | Bass C Jam [Byas a Drink; alt tk.] |

late December 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Savoy MG 12026) | Howard McGhee Orchestra | Down Home | late December 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Savoy MG 12026) | Howard McGhee Orchestra | Sweet and Lovely | late December 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Savoy MG 12026) | Howard McGhee Orchestra | Fiesta [Short Life] |

late December 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | (Savoy MG 12026) | Howard McGhee Orchestra | I'm in the Mood for Love | late December 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | unissued | Howard McGhee Orchestra | Out of Nowhere | late December 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | unissued | Howard McGhee Orchestra | Little Bird | late December 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | unissued | Jimmy McPartland | How High the Moon | late December 1947 | (Halcyon 116) |

| [Vitacoustic] | unissued | Jimmy McPartland | I Found a New Baby | late December 1947 | (Halcyon 116) |

| [Vitacoustic] | unissued | Jimmy McPartland | ? | late December 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | unissued | Jimmy McPartland | ? | late December 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | unissued | Jimmy McPartland | ? | late December 1947 | |

| [Vitacoustic] | unissued | Jimmy McPartland | ? | late December 1947 | |

| UB 9232 | 15A | Ethel Duncan, Soloist | Benson All Star Orchestra | Reminiscing of You Dear | c. September 1948 | April 1949 |

| UB 9230 | 15B | Benson All Star Orchestra | Benson—Bop | c. September 1948 | April 1949 |

| UB 9231 | 16A | Burress Courtney, Soloist | Benson All Star Orchestra | In Our World Alone | c. September 1948 | April 1949 |

| UB 9229 | 16B | Benson All Star Orchestra | Wiley Willie | c. September 1948 | April 1949 |

| PL-108 [Planet 103] |

17A | Bob Perkins Trio | Vocal Bob Perkins | Boogie Woogie Bowl | Janurary to March 1949 | May 1949 |

| PL-109 [Planet 103] |

17B | Bob Perkins Trio | Vocal Floyd Morris | Fool Again | January to March 1949 | May 1949 |

| PL101 [Planet 101/102] |

18A | Snooky & Moody (Vocal by Snooky) | Telephone Blues | November or December 1948 | May 1949 |

| PL102 [Planet 101/102] |

18B | Snooky and Moody (Vocal by Snooky) | Boogie | November or December 1948 | May 1949 |

| PL103 [Planet 103/104] |

19-A | Vocal by: Man Young | Accompanied by: Snooky & Johnny | My Baby Walked out on Me | November or December 1948 | May 1949 |

| PL104 [Planet 103/104] |

19-B | Vocal by: Man Young | Accompanied by: Snooky & Johnny | Let Me Ride Your Mule | November or December 1948 | May 1949 |

| 523Sw [Vitacoustic] |

20A | Kitty Stevenson | Hold Them Joe | c. December 15, 1947 | May 1949 |

| 524Sw [Vitacoustic] |

20B | Kitty Stevenson | With You | c. December 15, 1947 | May 1949 |

| 21? | ? | ? | ? | ? | |

| 21? | ? | ? | ? | ? | |

| M-1312 [Marvel 702-A] |

22A | Vocal Floyd Jones | Accompanied by Snooky & Moody | Stockyard Blues | November or December 1948 | July 1949 |

| M-1313 [Marvel 702-B] |

22B | Vocal Floyd Jones | Accompanied by Snooky & Moody | Keep What You Got | November or December 1948 | July 1949 |

| UB 9495 Sw | 23A | Four Shades of Rhythm | I Can Dream | c. November 1948 | July 1949 |

| UB 9497 Sw | 23B | Four Shades of Rhythm | Master of Me | c. November 1948 | July 1949 |

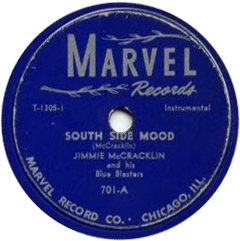

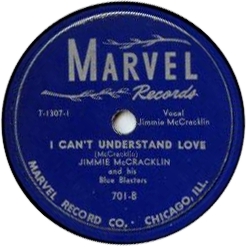

| T 1305-1 [Trilon 244] [Marvel 701-A] |

24A | Jimmie McCracklin and his Blue Blasters | South Side Mood | 1948 | July 1949 |

| T 1307-1 [Trilon 244] [Marvel 701-B] |

24B | Jimmie McCracklin and his Blue Blasters | Vocal Jimmie McCracklin | I Can't Understand Love | 1948 | July 1949 |

| T 1304-1 [Trilon 245] |

25A | Jimmy McCracklin and his Blue Blasters | When I'm Gone | 1948 | July 1949 |

| T 1306 [Trilon 245] |

25B | Jimmy McCracklin | Listen Woman | 1948 | July 1949 |

| 1145S [Sunbeam 104] |

A26 | Little Miss Cornshucks with Marl Young Orchestra | So Long | late September 1946 | September 1949 |

| 2675 [Sunbeam 105] |

B26 | Little Miss Cornshucks with Marl Young Orchestra | For Old Time's Sake | October 1946 | September 1949 |

| V 1952 SW-3 [Vitacoustic] |

33 | The Four Shades of Rhythm | Don't Blame Me | late December 1947 | September 1949 |

| V 1909 [Vitacoustic] |

33 | The Four Shades of Rhythm | Yesterday | December 1947 | September 1949 |

| UB 9510 SW | 1000 A | Joe Petrak | Accordion Solo and Orchestra | Lady of Spain | c. April 1949 | May 1949 |

| UB-9511 SW | 1000 B | Joe Petrak | Accordion Solo and Orchestra | Barbara Polka | c. April 1949 | May 1949 |

| 1001 | Joe Petrak | Accordion Solo and Orchestra | Vocal by Skip Farrell | The Christmas Waltz | c. April 1949 | December 1949 | |

| 1001 | Joe Petrak | Accordion Solo and Orchestra | Oh, Marie | c. April 1949 | December 1949 | |

| 1002 | Joe Petrak | Accordion Solo and Orchestra | Avalon | c. April 1949 | December 1949 | |

| 1002 | Joe Petrak | Accordion Solo and Orchestra | Fiddle Faddle | c. April 1949 | December 1949 | |

| UB 21938-SS [Miracle] |

1010A (Master 1010A) | Memphis Slim | Country Girl | c. September 1947 | December 1949 (March 1950?) |

| UB 21745-SS [Miracle] |

1010B (Master 1010B) | Memphis Slim | Believe I'll Settle Down | c. July 1947 | December 1949 (March 1950?) |

| UB9670 M1 (in wax, UB9670-MI with SW over the UB) [Miracle] |

1011A (Master 1011A) | Sonny Thompson and His Orchestra | The Fish-I | c. April 1949 | prob. December 1949 (after March 1950) |

| UB9793 M-2 (in wax, UB9793M2 with SW over the UB) [Miracle] |

1011B (Master 1011B) | Sonny Thompson and His Orchestra | The Fish-II | June 1949 | prob. December 1949 (after March 1950) |

About Detroit-based pianist and blues singer Kitty Stevenson we know a little (and what little we know is largely due to research by Marv Goldberg). Born on May 30, 1920, she had been appearing in Detroit clubs for much of the 1940s. In November and December 1947, she was working at Club Sensation, where T. J. Fowler had the house band. By 1949, she would be the regular female vocalist with the Todd Rhodes Orchestra. She recorded two singles with Todd Rhodes' band for Sensation, at a date that remains somewhat unclear. Because Todd Rhodes made four sessions in the second half of 1947, while Sensation and Vitacoustic were collaborating on the Jam Session Series, and T. J. Fowler did not record instrumentals or sides with other singers for Vitacoustic, we'd thought Kitty Stevenson she was backed by a Rhodes band on Old Swing-Master 10 and 20. But an item in the Detroit Tribune (December 20, 1947) indicates that she was just back from Chicago, where she'd recorded for Vitacoustic with T. J. Fowler's band. The article also lists 8 recognizable titles for the items she'd recorded. Kitty Stevenson recorded again with Rhodes for Sensation in 1950 and for King in 1951 (after Sensation went inactive, Rhodes' contract expired, and he was able to sign with the larger company). She became ill in July 1951 and died in Detroit Memorial Hospital in May 31, 1952, having just turned 32.

After Stevenson became ill, first Connie Allen and then LaVern Baker took her place with Rhodes. On December 28, 1952, Egmont Sonderling unloaded what were written down as 9 Kitty Stevenson tracks (including the four that had been issued on Old Swing-Master) to Art Sheridan of Chance Records. It appears that Sheridan separated one title into two, and that he had purchased 8 tracks. Chance issued none of these, but 7 of them appeared in 1977 on a P-Vine Special LP of Chance-derived material. The Chance documentation rendered her name as "Kitty Stevens," and discographies for years have treated these sides as though they were newly recorded for Chance. The original matrix numbers were probably V1938 through V1946 or V1941 through V1949.

As one of the most influential of all blues guitarists, Aaron Thibeaux "T-Bone" Walker (born in Linden, Texas, on May 28, 1910; died in Los Angeles on March 16, 1975) should need no introduction here. The story of his Rhumboogie sides, cut on October 10, 1944 and December 19, 1945, is told on our page devoted to that label; the sessions are also listed on our Red Saunders page. Old Swing-Master 11 contained two of the four sides from the December 19, 1945 session, none of which was ever released on Rhumboogie; there had been a previous release of "My Baby Left Me" with a different B side, on Mercury in October 1946. The December 19, 1945 session backed Walker with an 8-piece recording ensemble led by Marl Young. Lending an interesting edge to the proceedings, trumpet soloist Melvin Moore was leaning in the bebop direction, as was Young himself (one of his piano solos on the session sounds like the work of Thelonious Monk). T-Bone is in top form and the band was captured in excellent record quality for the period.

In 1952, Egmont Sonderling would deal all four sides from the 1945 session to Chance and to T-Bone's current label, Imperial. Major-league litigation was avoided because neither company did anything with them at the time. The sides eventually appeared on LPs many years later. (Constellation, a company partly owned by former Chance proprietor Art Sheridan, made the first move in 1964.)

Christine Randol was a singer who accompanied herself at the piano. Her name is misspelled "Randall" in most secondary sources. The correct spelling can be found in most Local 208 documents, on her Vitacoustic release, and on her Old Swing-Master release. According to Local 208 records, she was born on December 25, 1915. The contract lists maintained by the local show that she worked in Chicago from 1946 through the early 1960s. Most often she appeared in the clubs as a single. She was married to jazz musician Frank Gassi (1909 - 1952), who played guitar in Eddie Wiggins' sextet when it recorded for the Sultan and Bullet labels (we are grateful to Vince Gassi, Frank's nephew, for this information). In fact, her Local 208 file card identifies her as Chrisine Gassi Randol. Her husband was working a day job on the El (Chicago's elevated train system) when he was electrocuted in an accident in Feburary 1952.

The backing on the Old Swing-Master release from Randol's Vitacoustic session is extremely spare: just her piano and a string bass. We haven't heard her release on Vitacoustic 1006, which is so rare we didn't know it existed until 2020. From the matrix numbers the session appears to have taken place at the eleventh hour, not long before the recording ban went into effect on January 1, 1948. Her sides are the very last that we know of in the V1800 series. They are also her only known recordings.

The Four Shades of Rhythm came together in Cleveland in 1945. The original members were Oscar Lindsay (drums and vocals), Willie Lewis (guitar), Sim London (piano), and June Cobb (bass). For the next few years the group, with some personnel changes, toured around the Northeast and took some engagements in Chicago. They returned to the city in late 1947; by this time Eddie "Bones" McAfree had taken over at the piano bench. The group now consisted of Lindsay, Oscar Pennington (guitar), Eddie McAfee (piano), and Eddie Meyers (bass).They cut "One Hundred Years from Today" b/w "Howie Sent Me" on Vitacoustic 1005; these sides were recorded during the frantic activity of December 1947 and just made it out in January 1948 before Vitacoustic had to file for bankruptcy. The Four Shades made a second session even closer to B-day, right after the Kitty Stevenson session in the Vitacoustic matrix series; this one never appeared on the parent label but was picked up by Old Swing-Master (we don't know what happened to V 1951 from the second session). Most of the sides that the group made for Vitacoustic ended up in the hands of Bernie Besman of Sensation, who never released anything from them, but eventually sold the masters in his possesion to Modern (which never did anything with them, either). What was meant to be a two-sided 78 from one of the sessions finally showed up in 2019, as a 45-rpm single from Ace Records. For the next 17 months the group remained in Chicago; during their extended stay they recorded once again, with the same personnel, in a free-lance session directed by Al Benson (the matrix numbers suggest that this took place around November 1948—that is, before Old Swing-Master opened).

Disillusionment set in for the group after the failure of their Old Swing-Master sides, and in 1951 Pennington and Meyers returned to their hometown of Cleveland. They were replaced respectively by Adam Lambert (late of the Cats 'n' Jammer Trio) and bassist Booker Collins, who had spent years with Andy Kirk's big band, then played in Floyd Smith's long-running trio (for more on the Smith trio see our Hy-Tone page). In 1951, the group cut a whole album's worth of material in Milwaukee, apparently for demo purposes; never released, the acetates from this session show off the breadth of the group's repertoire. This version of the group then made a single for Chance in 1952; around the same time Chance bought a little of their Vitacoustic material, but never issued any. A later group using the Four Shades name cut one single for the Apex label in 1959, which included a remake of "One Hundred Years from Today." They made their last recording in 1960 (for Tommy "Madman" Jones' low-circulation Mad label), then commercially allied with Apex. When interviewed by Peter Grendysa in 1983, Oscar Lindsay was still leading a trio in Chicago.

Tom Lord's Jazz Discographygives January 1949 as the recording date for the two Four Shades numbers on Old Swing-Master 13. Since Lord offers no matrix numbers and doesn't mention any of the other Four Shades sides for the label, this date can be safely discounted.

Trumpeter Howard McGhee's solitary release on Old Swing-Master was the only visible trace, for nearly a decade, of a much larger mass of material. McGhee, who was born in Oklahoma City on March 6, 1918, was already becoming known in Swing bands (he recorded with Andy Kirk in 1943) before he switched his allegiance to bebop. During a West Coast stay, he recorded with Coleman Hawkins in 1945, with his own band later the same year and in early 1946 (he had Tom Archia in his band for in January and Feburary 1946, but that edition went unrecorded), and with Charlie Parker in 1946 and 1947 (before and after Bird's forced rehab stint at Camarillo). McGhee, who came to the attention of Vitacoustic while on tour with Jazz at the Philharmonic, recorded no fewer than four sessions as a leader for the label during the last quarter of 1947. When Old Swing-Master took over the remains of Vitacoustic, two of the McGhee sides were issued with misleading titles (we have put the correct titles in brackets; the titles of some other tracks that later appeared on Savoy are equally bogus). The rest stayed in the vault. In December 1952, Egmont Sonderling unloaded 9 McGhee masters to Art Sheridan of Chance Records, but there is no evidence that Chance issued any of them. Finally, in 1955, Al Benson sold 12 McGhee masters (plus two alternate takes) to Savoy Records. That same year Savoy put out the 12 tracks that it had acquired on an LP, Savoy MG 12026. In the late 1970s, Savoy SJL 2219, Maggie—The Savoy Sessions, consolidated on 2 LPs all of the material acquired from Benson, including the two alternate takes, with two other sessions that were recorded off McGhee's broadcasts in the Philippines and Guam during 1951 and 1952. While doing research for SJL 2219, Art Zimmerman was able to check the audition acetates that Benson had provided to Savoy.

From Zimmerman's research, we know that the first four McGhee titles for Vitacoustic were cut the day after a Jazz at the Philharmonic Concert in Chicago, which places them on October 15 or November 10, 1947. Tenor saxophonist Kenny Mann, still a teenager at the time, had played in a local group that opened one of these JATP concerts, and was invited by McGhee to make the Vitacoustic session. (Mann was already an alumnus of the Lionel Hampton Orchestra, where he worked from late December 1946 through at least April 1947. In 1950 he would participate in Al Benson's TV show band and record for Seymour, before taking jobs with Ralph Marterie's society band and ultimately leaving the music scene to become a lawyer.) The rest of the lineup was drawn from the JATP touring ensemble: Billy Eckstine (sticking to valve trombone on this occasion), Hank Jones (piano), Ray Brown (bass), and J. C. Heard (drums). Local bebop vocalist Marcelle Daniels sang on "Flip Lip" and "The Last Word." Ted Hallock's Chicago column in the December 31 Down Beat (which went to press nearly 2 weeks earlier), stated that "Howard cut four sides for Vitacoustic and four for Dial before B-Day. One side scratched was a McGhee horn solo, MAN I LOVE" (p. 4). In fact, a session by McGhee and other JATP musicians had already been mentioned in Billboard on November 22. It appears that the original Vitacoustic matrix numbers on these were V1896 through 1899.

The bulk of the McGhee material was cut in three different sessions that took place during the last 9 days of December 1947, while McGhee's combo was starting a month-long gig at the Argyle Lounge (according to the December 31 Down Beat, the engagement commenced on December 23). The late-1970s Savoy release gives February 1948 as the date, but McGhee was no longer in town by then, Vitacoustic was filing for banktuptcy, and the most solvent of labels is unlikely to have braved the wrath of the Musicians Union during the initial phase of the second Petrillo recording ban, which was enforced with some rigor in Chicago. (This, after all, is the same Musicians Union that would shut Chance Records down for over 6 months in 1951-1952 because it had used non-Union session men.) The lineup for all three sessions (which produced 12 known tunes) was McGhee (trumpet), Jimmy Heath (alto and baritone saxes), Milt Jackson (vibes), Will Davis (piano), Percy Heath (bass), and Joe Harris (drums). On "Yardbird Suite" and "Out of Nowhere" Eckstine-style balladeer Earl Coleman sang. McGhee (when interviewed by Zimmerman) also recalled doing another Vitacoustic session that week, with a big band under someone else's leadership. (We think the leader alto saxophonist Johnny Bothwell, who was briefly advertised as a Vitacoustic artist.) But these items remain completely untraced.

We'll let Art Zimmerman explain how most of these McGhee recordings ended up at Savoy:

Eight other titles from the December [McGhee] sessions, plus the four with Kenny Mann, [Al Benson] sold to Herman Lubinsky of Savoy. Apparently, for purposes of audition, Lubinsky was furnished with two 16-inch acetate transfers containing a total of 16 tracks, in all. Probably, in order to prevent Lubinsky from issuing the material without first paying, Benson added brief bursts of multi-frequency beep tones, much like Morse code, about every fifteen seconds. Lubinsky must have paid for only twelve titles. The Savoy files had only tape copies of the recordings, not the original masters that Benson must have had.... In addition to the twelve sides issued by Savoy, the four titles on one of the discs include the two issued on Old Swing-Master plus two that were never issued in any form, Out of Nowhere and Little Bird,the latter tune named for Jimmy Heath.

Old Swing-Master 14 poses one more quandary: mismatched matrix numbers. The matrix number for "Yardbird Suite" was V892 SW. Peeling off the SW (Swing-Master) suffix gives us a Vitacoustic master number, in a continuation of the U600 series rather than the V1800 series. The implication is that "Yardbird Suite" was mastered while Vitacoustic was still extant. The matrix on "Donna Lee," however, is UB 9110 SW. This comes from the UB9000 series of United Broadcasting Studios, and implies a date in August or September 1948. The implication here is that in 1948 Sonderling was already mastering some Vitacoustic material that he hoped to sell in partial recoupment of his losses. The V892 matrix implies that one session took place at Universal Recording instead of United Broadcasting; since there is a gap in the V1800 series between V1910 and 1918, it's likely that the rest of the McGhee sides originally bore numbers in this range.

We know a lot less about the Vitacoustic recordings of cornetist Jimmy McPartland. McPartland was by this time a veteran of the Chicago scene, having appeared on his first record in 1924, when he had the unenviable task of replacing Bix Beiderbecke in the Wolverines. In the January 14, 1948 Down Beat,Ted Hallock praises McPartland's current band, then working the Capitol Lounge on State Street. The band included Jack Golly (cl, as); Marian McPartland (p, arr); Ben Carlton (b); and Chick Evans (d); it was playing an eclectic repertoire that Jimmy McPartland referred to as "Dixie-bop." In passing, Hallock comments that "Jimmy managed to record six sides for Vitacoustic before B-Day" (p. 4). Whether these were intended for release in the "race" series or the pop series we don't know; Vitacoustic didn't last long enough to put any of them out. We are listing them here because Egmont Sonderling probably acquired them, but there is no known release on Old Swing-Master either. Two tracks said to have been recorded in "Chicago, 1948" by this same lineup were issued in the 1970s on an LP on Marian McPartland's Halcyon label, along with material recorded for Unison in 1949 and Prestige in 1950. (Unison was, in fact, the McPartlands' own label, formed after the Vitacoustics failed to appear and other labels failed to record the band; four newly released sides on Unison were reviewed in Down Beat on October 21, 1949.) Since Hallock points to the McPartland group's performances of "How High the Moon" as proofs of its modernity, we can be reasonably sure that these two LP tracks are one-third of the missing Vitacoustics. The McPartland sides may have also borne V1800 numbers between 1910 and 1918.

There is no doubt that Al Benson produced Old Swing-Master 15 and 16, by the Benson All Star Orchestra. This was a pretty impressive aggregation of local musicians; it consisted of Melvin Moore (trumpet), Willie Randall (alto saxophone), Eddie Johnson (tenor sax), Buddy Hiles (baritone sax), Burrington (so referred to on the label, but usually spelled Barrington) Perry (piano), Rail Wilson (bass), and Oliver Coleman (drums). From Charles Walton's interview with trumpeter Lewis "Bill" Ogletree (the interview is among the Bronzeville Conversations listed at http://jazzinstituteofchicago.org/index.asp?target=/jazzgram/bronzeville.asp), we gather that the orchestra was a cut-down version of a band that Ogletree had put together under Al Benson's sponsorship to play at the Savoy Ballroom during its last days. Benson posted an indefinite contract with the Savoy on April 15, 1948 (the notation WGES on the Local 208 list indicates that live broadcasts were included in the package). The band probably worked the Savoy on weekends until the venerable ballroom folded in July.

As Ogletree told Charles Walton:

I had a band for Al Benson for a long time. We played his broadcast from the Savoy Ballroom. It was my band but I let Paul King take charge because he was doing a little arranging as well....

Besides Paul King and me, Calvin Ladnier was on trumpet; Willie Randall, Eddie Johnson, Nat Jones, Mac Easton, saxes; Ruth Murray, piano; Oliver Coleman, drums; and Quinn Wilson, bass. We were getting $11.58 per man for that job.

Benson put the recording session together after the Savoy had closed and the band broken up. For some reason Ogletree wasn't available, but Willie Randall, Eddie Johnson, and Oliver Coleman had been in the Savoy band, while Barrington Perry and Rail Wilson were regular members of violinist Leon Abbey's trio. Willie Randall was the de facto leader; he got composer credit on all four sides and appears to have been the arranger on the ballads. Following a standard commercial strategy at the time, the band cut two up-tempo instrumentals and two schmaltzy ballads: Burress Courtney was the rather syrupy baritone singer on "In Our World Alone"; on "Reminiscing of You Dear," soprano Ethel Duncan, who later worked with King Fleming's combo, did the vocal honors. The ballads were also designated as the A sides.

The B sides ("Wiley Willie" and "Benson—Bop") were bop numbers; the trumpet soloing by Melvin Moore goes as expected, but bop soloing by Willie Randall and Eddie Johnson is a rare treat. The matrix numbers on Old Swing-Master 15 and 16 are in the UB 9000 series from United Broadcasting Studios, and indicate a recording date in the early Fall of 1948. In other words, Benson had gone into the studio the year before to produce them "on spec" and had not been able to sell the masters to another label at an agreeable price. In fact, this is the first studio session that Benson is known to have supervised (he had done some clandestine live recordings at the Pershing Ballroom in the spring of 1948, featuring Gene Ammons and Tom Archia; six sides' worth of these were released on Aristocrat in 1948 and 1949).

In snapping up pioneering down-home blues recordings by Snooky Pryor, Moody Jones, Floyd Jones, and Johnny "Man" Young, Old Swing-Master was trying to get in on the action after Aristocrat's big local success with Muddy Waters in June of 1948. Al Benson of course had some notion of the local demand for these records. He got these items from the microscopic Marvel and Planet labels. Snooky and Moody, Man Young, and Floyd Jones all recorded for Chester A. Scales, who operated a couple of small record stores on the Near North Side. Scales was probably in partnership with someone who worked at the Chicago distributor for the Trilon label, which was based in Oakland, California. Indeed, some Trilon material also appeared on Marvel; see the entry on Jimmy McCracklin below. e may also have cut in someone who worked at Planet Record Sales, a distributor located at 831 South State. It is even possible that Scales owned a piece of that distributor, which was rather short-lived (in business in March 1948, out of business by the time the 1949 telephone book was published).

James Edward "Snooky" Pryor was born on September 15, 1921, in Lambert, Mississippi. His style on the harmonica was derived in roughly equal parts from John Lee "Sonny Boy" Williamson and Aleck Miller (aka Sonny Boy Williamson #2). He got the idea of amplifying his harmonica while serving in the military during World War II, and began performing along Maxwell Street with portable amplification in 1945. The sides that he made in final months of 1948 for Planet and Marvel were his first recordings. The Snooky and Moody sides initially released on Planet were recorded, Pryor recalled, at a studio on Wacker Drive, which probably means Universal Recording. The Man Young and Floyd Jones items were recorded at the same session; Johnny Williams recalled that it was done at "United Studios on the North side," which would mean United Broadcasting.

Since the Planet and Marvel releases are incredibly scarce, and CD reissues of these titles are apparently dubbed from the Old Swing-Master 78s, we can fairly credit Benson and Sonderling for preserving some historically important music. Snooky Pryor subsequently recorded for JOB, Parrot, and Vee-Jay; after a long period of retirement, he became a hit on the blues revival circuit with a Blind Pig release in 1987, and continued to record into the 1990s. He died in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, on October 18, 2006. Snooky's partner on Old Swing-Master 18 and 22, Moody Jones, played guitar and bass; he was born in Earle, Arkansas on April 8, 1908, and died in Chicago on March 23, 1988.

John O. Young, known as "Man" because he played mandolin as well as guitar, was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi, on January 1, 1918. He had previously recorded in 1947 for Ora Nelle, a back-of-the-record-store operation on Maxwell Street. In November or December 1948, shortly after the Snooky and Moody session, Chester Scales recorded him for Planet, which was the source for his reissue on Old Swing-Master 19. During the blues revival of the 1960s, Johnny Young recorded for Arhoolie and Testament; he died on April 18, 1974 in Chicago. On his Old Swing-Master release, Young sang and played mandolin; the accompaniment was by Snooky Pryor on harmonica and Johnny Williams on guitar. According to the musicians' recollections, the Snooky and Moody and Man Young sides were recorded the same day, at a studio on the North Side (probably United Broadcasting).

Guitarist Floyd Jones, Moody's cousin, was born on July 21, 1917, in Marianna, Arkansas, and arrived in Chicago in the mid-1940s, playing on Maxwell Street with Baby Face Leroy Foster and Moody Jones. At some point in 1948, Floyd Jones recorded for Tempo Tone with Sunnyland Slim. Chester Scales was planning to use Floyd Jones on the Snooky and Moody session, but on the day of the session Jones could not be found. Not long afterward, Scales recorded Jones as a leader (with Pryor on harmonica and Moody Jones on second guitar—not string bass as stated in sources) and his sides first saw release on Marvel. "Keep What You Got" (a number associated with Howlin' Wolf) delivers its admonitions in a disarmingly jaunty fashion. A plaint about unemployment and rising prices, "Stockyard Blues" is closer in tone to Floyd Jones' later recordings. With their easy, unforced rhythm and superbly integrated ensemble, both sides are major contributions to the down home blues trend that was emerging in Chicago.

Beginning in 1951, Floyd Jones would record for JOB, Chess, Vee-Jay, and Testament; in his later years, he switched to electric bass. He died in Chicago on December 19, 1989. Floyd Jones' second rendition of "Dark Road," cut for Chess in December 1951 in fratricidal competition with his JOB version, is regarded as a blues classic.

Sonderling and Benson took over Planet's entire release series, which meant they also picked up a jazz-oriented single by the Bob Perkins Trio. Perkins was a Chicago-based alto saxophonist who had picked up some ink in the The Billboard 1944 Music Year Yearbook. The yearbook ran two photos of "Bob Perkins The Sax-o-maniac and his Swing Quartet" with Earl Hyde on drums, George Dawson on guitar and Everette McCrary on bass (our thanks to Bo Sandell for information on this source). Perkins showed up occasionally as a leader in the Local 208 contract lists from this period: for instance, his contract with the General Lounge for 2 days was accepted and filed on September 5, 1946; he followed this up with a 4-week contract (posted October 3). He then moved over to the Sky Club (2 week contract accepted and filed on November 7, 1946). Perkins resurfaced as a leader at Jimmy's Palm Garden (6 weeks with an option; contract filed on May 15, 1947). The Palm Garden contract was extended on July 3 (6 more weeks, with a 12-week option). By early November Perkins was at the Rag Doll (indefinite contract posted on November 6; another contract for 5 days only was posted on February 5, 1948, and on May 6, 1948 Perkins posted another contract for 3 weeks and 2 days). On June 3, 1948, Perkins announced his move to Green Parrot by posting a 10-week contract; on August 5 his indefinite contract with Jimmy's Palm Garden was accepted and filed. Then on November 4, 1948 he filed a 2-week contract with Club 21 and an indefinite contract with the Rag Doll. From early January through late March 1949 his trio with Floyd Morris on piano and Norman "Flip" Gaines on drums was working as the house band at the Music Bowl, a club in the Loop (Local 208 contract list, January 6, 1949; Down Beat, "Chicago Band Briefs," March 25, 1949, p. 4). "Boogie Woogie Bowl," a Louis Jordan-style number, commemorates this establishment.

Old Swing-Master 17 was a straight reissue of Planet 103: the matrix numbers and artist credits are the same as on the Planet. "Boogie Woogie Bowl" was designated as Side A.

In any event the Billboard review was unfavorably disposed toward "Boogie Woogie Bowl," giving it ratings of 46-46-44-48: "Unpromising novelty ditty in boogie tempo gets a mediocre warbling and instrumental rundown by a sax-piano-drums trio." Maybe the reviewers were sated with Louis Jordan; heard with today's ears, Perkins' patter is enjoyable, the band swings, and his alto sax solo is buoyant "Fool Again" did a little better, at 55-57-55-53: "Warbler and sax compete to be heard on a modern ballad number of some promise." This lounge ballad, featuring smooth baritone crooning by Floyd Morris, is in a dated genre, but Perkins' accompaniment and solo are refreshingly low on schmaltz. Matters of taste aside, skepticism about Old Swing-Master's distribution definitely helped to lower the numerical ratings.

Perkins would continue to appear sporadically in Chicago through 1952, occasionally scoring gigs at prominent establishments like the Blue Note. He made one more 78, around December 1950 for a label called Mar-Vel', which was out of Hammond, Indiana (our thanks to Paul Solarski, email communications of December 6, 2022, for alerting us to this extremely rare release and providing label photos and dubs). Although Mar-Vel' mostly recorded Country music, its owner, Harry Glenn, showed an interest in the Bob Perkins Trio (by the end of 1950, the pianist and drummer not the same musicians Perkins had recorded with for Planet). On Mar-Vel' 800, Perkins can be heard doing "Drinking Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee" and "Dinah." The latter gives him ample solo space on the alto sax. After 1952 we have found no further trace of Bob Perkins on the Chicago scene.

Floyd Morris left the Perkins trio in October 1950. Morris worked the clubs during the 1950s, often playing solo or leading his own trio. For a brief time, in 1951-1952, he was the pianist for the Four Shades of Rhythm. Morris recorded occasionally, for Vee-Jay with Red Saunders on drums, for Salem while he was a member of Johnnie Pate's trio (he appeared on two LPs), and for Federal and Chess in bands again led by Pate. In the 1960s and 1970s Morris was a major session player for the thriving Chicago soul music industry. He died in 1988.

The sides by pianist and singer Jimmy McCracklin were originally made for Trilon: Old Swing-Master 24 was a straight reissue of Trilon 244, and Old Swing-Master 25 recycled Trilon 245. Both of these had been recorded in Oakland, California, where McCracklin was based at the time. Trilon 244 had also made an appearance in Chicago as Marvel 701 (where the artist's first name was spelled "Jimmie"; we have yet to see the labels to Old Swing-Master 24). Jimmy McCracklin was born on August 13, 1921, in Saint Louis. He began to make records in 1945 for Globe on the West Coast. Trilon was a little outfit in Oakland, run by Rene LaMarre. It had some connection as well with local entrepreneur Bob Geddins (whose imprints included Big Town, Down Town, and Gilt Edge). Trilon opened in 1946 and was responsible for at least 43 releases (the first recordings by blues guitarist Lowell Fulson are the most important historically) but the company was winding down—in fact, Trilon 244 and 245 would be its very last releases.

In March 1948 (according to the Chicago phone book) there was a Trilon Record Distributing Company at 1208 South Spalding in Chicago, which apparently closed down at some point in 1949. Apparently someone at the Trilon distributor went in with Chester Scales on the Marvel releases—possibly also on the Planets; this same person arranged the reissue of Trilon 244 on Marvel and subsequently made a deal with Old Swing-Master. McCracklin has had a long career in R&B, with subsequent stops at Modern, Swing Time, Peacock, Imperial, Hollywood, Irma (a latter-day Geddins operation), Checker, Mercury, and Minit. Most recently he has recorded for Bullseye Blues.

Little Miss Cornshucks became much less active as a performer after she suffered a nervous breakdown in 1951. She retired completely after her last recording session, done for Chess in 1960. She died in Indianapolis on November 11, 1999.

John L. Chatman, aka Peter Chatman, aka Memphis Slim, is covered in some depth on our Miracle and Hy-Tone pages. On Old Swing-Master 1010, which is derived from two of his 1947 sessions for Miracle, Slim (piano, vocals) was accompanied by Alex Atkins (alto sax), Ernest Cotton (tenor sax), and Ernest "Big" Crawford (bass).

Egmont Sonderling also obtained two Miracle sides by Sonny Thompson's popular unit, which appared on Old Swing-Master 1011 as "The Fish-I" and "The Fish-II." These were actually recorded at two sessions in 1949 with different bands. But the formula had proven remarkably successful when sides from two 1947 sessions were assembled into Thompson's two-sided hit "Long Gone," and Sonderling was not adverse to trying it again.

We have heard occasional tales of releases appearing on Swing-Master, without the Old. We haven't seen any copies with such labels, but veteran collector Robert Javors recalls two Swing-Masters coming briefly into his possession in the 1970s when he was buying up 78s in large quantities and auctioning them off. One of these, he says, was a Swing-Master 10 (the Kitty Stevenson single with a different label). We are eager to hear from collectors who have 78s with this variant in their possession.

As 1950 rolled around, Egmont Sonderling had a new business plan in mind; to implement it he began to phase out his recording enterprises. First, he sold his pressing plant to Art Sheridan's Armour Plastics. In Billboard for March 11, 1950, the announcement was made that "Master Record pressery here, operated by Egmont Sonderling, of United Broadcasting, is combining some of its equipment with that of Armour Plastics, pressery operated by Art Sheridan. New plant will enlarge to more plating equipment and will also wax 16-inch e.t.'s [extended transcriptions]." In July, Sonderling sold what was left of his plating operation. The new manager was one Alois T. Daniel, who was going to run it on behalf of Armour Plastics. The December 1950 Chicago phone book listed Armour Plastics—but not Master Records. This deal with Art Sheridan may explain how several batches of Old Swing-Master items came to be sold to Sheridan's Chance label in 1952.

Once Sonderling unloaded his pressing plant, Old Swing-Master's days were numbered. In June 1950 Billboard reported that Leonard Davis had jumped ship to the Chess operation (formerly Aristocrat; Leonard and Phil Chess had just renamed it). He was described as ex-sales manager at Old Swing-Master, which Billboard said was "once operated by Negro d.j. Al Benson and Egmont Sonderling" but had now folded. The following week, however, Billboard backtracked and said the label was not folding after all, according to Sonderling, who said that the firm was planning on releasing some sides by T-Bone Walker and Kitty Stevenson. But these never materialized. The operation was effectively dead when Leonard Davis departed. And now if Sonderling really wanted to release more Old Swing-Masters, he would have had to pay someone else to press them.

The Master label, also in a wind-down phase, put out a little more Miracle-derived material in March 1950. Besides the items already mentioned, there were Master 1020 and Master 1030, both consisting of Memphis Slim sides not previously issued on Miracle. And there was a Jack Cooley single on Master 102, a mid-1950 release derived from Miracle's successor label Premium—see those pages for details.

After the Cooley single and the closedown of Old Swing-Master, Egmont Sonderling was effectively out of the record business. In November 1950, his new business direction became public when he opened radio station WOPA in the Chicago suburb of Oak Park.

Sonderling's United Broadcasting Studio was still doing steady business recording for independent labels in 1950. In 1951 its output slowed down, leading to one pop release on Master with just the matrix numbers on each side (since Elaine Rodgers was one of the vocalists, we have commented on this single on our Chance page). The next year was slower still; around the end of 1952 there was one Master (by pianist Ronnie Orland) that just carried its matrix numbers (UB52-563 and 564). The Orland session was dealt to Rondo.

Tom Kelly has a 78-rpm dance music single (by Al Saber, Vocal | David Le Winter's Orchestra) on maroon-label Master 1001/1002. The matrix numbers are UB-53-51 for Master 1001 "Love Me Love Me," and UB-53-52 for Master 1002, "What Is There to Say," indicating a 1953 recording date. (1001 also bears K 1106 in the vinyl while 1002 has K 1107.) David LeWinter started leading the band at the Pump Room in the Sherman Hotel in 1945; composed of several highly accomplished musicians, it played pop music for dancers. LeWinter had been with bigger companies; he signed with Mercury in December 1949 and spent two years with the label. This disk, which Sonderling probably put out as a favor to somebody, appears to be the last gasp for the Master 1000 series. We figure it was close to the end of the road for United Broadcasting Studio as well (we don't know exactly when UB closed down).

Recently, another maroon-label Master has surfaced—a polka band record with Buddy Beek (who was based in Milwaukee) as the leader. More to follow—first we have to find a good enough picture of the label to be able to read the numbers.

In later years, Sonderling concentrated on his Sonderling Broadcasting Corporation (we are indebted to his obituary in the New York Times for details). At its peak, the Sonderling operation included 11 radio stations in major markets, a TV station (WAST, the CBS affiliate in Albany, New York), and a movie theater chain in New York and the New England States that included 55 screens. In 1974, Sonderling Broadcasting's Black-oriented radio stations were located in Chicago, New York City, Washington, DC, Memphis (he had acquired the legendary WDIA), and Oakland. In 1980, most of Sonderling Broadcasting was sold to the Viacom conglomerate. Sonderling retained two radio stations in Chicago and the movie theater chain, but in 1987 he sold his remaining holdings and retired to the wealthy enclave of Bal Harbour, Florida. Egmont Sonderling died on July 22, 1997, at a cancer center in Miami.

The collapse of Old Swing-Master took Al Benson out of the record business temporarily. Benson resumed freelance recording in March 1951 (with an Eddie South session that he sold to the Chess brothers). After building up his recording activity in 1952, he gave his new Parrot label a preliminary launch in December of 1952 (still in close coordination with Chess), then went out on his own in June 1953. In 1954, Benson added the Blue Lake subsidiary to Parrot, which he sustained until the beginning of 1956, when he sold the company to John Henry "Lawyer" Burton.

We are including this appendix because in May 1949, Old Swing-Master concluded a deal to distribute three 78s (6 sides) drawn from of a limited-edition album of four 78s that was put out by the tiny Jazz Ltd. label. Bill and Ruth Reinhardt started the label to record some of the traditional jazz artists who performed at their club, Jazz Ltd., at 11 East Grand Street.

In March 1949, Jazz Ltd. put out a limited-edition album of 4 78s. (The album was intended for promotional purposes, and only 1000 copies were made). There were three sides by soprano saxophonist Sidney Bechet and the club's house band, probably cut in late August 1948; a fourth side from the same session featured the band's pianist Don Ewell in a trio format. A second session featured the Jazz Ltd. house band in February 1949; on two sides the club's current headliner, Muggsy Spanier, played lead cornet; on the other two he was replaced by cornetist Paul "Doc" Evans, who had been previously featured for two long engagements at the club. Both sessions added a string bass player to the club's usual quintet of three horns, piano, and drums. Bill Reinhardt was the clarinetist in the house band throughout this period; he appeared on both sessions. See our Jazz Ltd. page for more about the proper dating and personnel.

In the chart below, the March 1949 date applies to the original album release on the silver and red Jazz Ltd. label. The June 1949 date applies to the singles issued separately on the gray and red Jazz Limited label, as distributed by Old Swing-Master. The "et al."'s indicate that each Jazz Ltd. listed the entire personnel (though we are skeptical about the drummer identifications on the labels to 101 and 201). We have included Jazz Limited 301 for completeness, even though Old Swing-Master chose not to pick it up.

To our knowledge, the JL suffix that we have for the matrix numbers of Jazz Limited 101 and 401 appeared on both the original album and the separate singles reissued under the Old Swing-Master deal.

| Matrix number | Release number | Artist | Title | Recording Date | Release Date |

| UB9101-JL | Jazz Ltd. 201A | Sidney Bechet et al. | Maryland, My Maryland | prob. late August 1948 | March 1949 (June 1949) |

| UB9102 JL | Jazz Ltd. 201B | Sidney Bechet et al. | Careless Love | prob. late August 1948 | March 1949 (June 1949) |

| UB9103 JL | Jazz Ltd. 101A | Sidney Bechet et al. | Egyptian Fantasy | prob. late August 1948 | March 1949 (June 1949) |

| UB9104 JL | Jazz Ltd. 101B | Don Ewell et al. | Maple Leaf Rag | prob. late August 1948 | March 1949 (June 1949) |

| UB9181 JL | Jazz Ltd. 301A | Doc Evans et al. | Wolverine Blues | February 1949 | March 1949 (no reissue) |

| UB9182 JL | Jazz Ltd. 301B | Doc Evans et al. | It's a Long Way to Tipperary | February 1949 | March 1949 (no reissue) |

| UB9183 JL | Jazz Ltd. 401A | Muggsy Spanier et al. | A Good Man Is Hard to Find | February 1949 | March 1949 (June 1949) |

| UB9184 JL | Jazz Ltd. 401B | Muggsy Spanier et al. | Washington and Lee Swing | February 1949 | March 1949 (June 1949) |

The original issue numbers are derived from George Hoefer's detailed review of the Jazz Ltd. album, in Down Beat, June 3, 1949. The Jazz Limited releases are mislisted in Lord's Jazz Discography: there is no mention of the original album, nor of the fact that 101, 201, and 401 reappeared as separate 78s under the Old Swing-Master deal while 301 did not. Moreover, Lord puts "Egyptian Fantasy" on a non-existent 202, stranding "Maple Leaf Rag" on 101 without a flip side!

As we noted, the two Doc Evans sides were left out of the Old Swing-Master deal, though they have appeared on subsequent reissues. George Hoefer's Down Beatreview complained of "fuzzy" sound on them—perhaps Sonderling and Benson found this a deterrent? (The trouble must have been a pressing fault, as a 78 we have heard sounds OK, and the LP and CD reissues do as well).

The distribution deal ended when Old Swing-Master did, in June 1950. In June or July, Jazz Ltd. promptly licensed all 8 sides to Regal, which put them on a 10-inch LP (Regal LP 11). There was also a limited edition LP on Jazz Ltd.'s own label, distributed out of the club. Regal went out of business in October 1951. The Reinhardts then cut another deal with Atlantic, which would reissue the sides on a 10-inch LP in 1952, and again in the 12-inch format in 1957.