Revision note: Marv Goldberg's recent research on Bob Carter had led to some revisions and corrections here. At least two Bob Carters were on the Chicago music scene at the same time. We used to think that the Bob Carter who led the bands on two later studio sessions (for Rim in 1949 and for Cool in 1953) was not the Robert James Carter who recorded for Sunbeam. Now, for reasons that are explained below, we've concluded that he was. Courtesy of the 78 rpm collection at Internet Archive, we've finally acquired label copy for Johnny Hartman's debut record, Sunbeam 108. We've adjusted the dates on the company's early sessions at the Myron Bachman Studio, taking into account what we've learned about recordings for other labels that were made there.

The Sunbeam label was a short-lived enterprise in Chicago just after World War II, operating from September 1946 to September 1947. It was the project of pianist and arranger Marl Young, who during the war years had led bands in the some of the major clubs in Chicago, notably the Rhumboogie and Joe's Deluxe Club, and done substantial arranging for bands at the other major black and tans, such as the Grand Terrace, the Club DeLisa, and Club Plantation. In the Sunbeam operation, Young selected, arranged, and recorded the music, while his brothers, who ran a dry cleaning business, handled the company's business affairs. (His brother Harry Young was credited as co-composer on three titles that were issued on the label.)

Marl Henderson Young was born in Bluefield, Virginia, on January 29, 1917. In 1922, his mother moved the family to Chicago, where (despite living across the street from Du Sable), he resolved to avoid "minority schools"; he graduated from Englewood High School. He started piano lessons at age 6 and was classically trained on the instrument; he was playing jobs at 14 and joined Musicians Union Local 208 in 1933, when he was 16. He got his formal education at Chicago Musical College in the Loop. On graduating from high school he joined Reuben Reeves' big band, which made an Eastern tour in 1934 (temporarily stranding him in Baltimore). After playing piano in Floyd Campbell's aggregation (through early 1942), he started his own band. His first recording (as "Merle" Young) was a session with Floyd Campbell and his Gang Busters for Bluebird, done in Chicago on October 1, 1940. Our thanks to Mario Schneeberger (http://www.jazzdocumentation.ch/mario/marlyoung.pdf) for pointing this out. According to Schneeberger, one single, Bluebird B-10852, was released from the session (the other two titles were rejected) and Young soloed on "Blow My Blues Away."

In 1942 Young was simultaneously working as an independent arranger for big bands at the Regal Theater, the Club DeLisa, the Grand Terrace, and Dave's Cafe´. Young organized his first band in February 1942; like Floyd Campbell's outfit it performed one-off gigs such as the annual Sadie Bruce Dance Revue. In April and May of 1942, Young was working at New Club Plantation as an arranger for the acts there, but on May 10 the club closed (while still owing Young money for some of his arrangements). Young soon picked up another steady job, however, at one of the biggest black and tans on the South Side; he began writing arrangements and directing the floor show at the Rhumboogie Cafe in the summer of 1942, shortly after it opened.

During most of 1943, Marl Young led the house band at Joe's Deluxe Club, accompanying Valda Gray and his/her team of female impersonators. Probably in November 1943 club owner Charlie Glenn signed Young on to the new "Dream Band," an ensemble that Glenn gradually put together after Richard Overton's band lost most of its young members to the draft. (Overton himself had become the leader only after the band's founder, King Fleming, was drafted.) How Young found the time we don't know, but he also completed a law degree at John Marshall Law School in 1943.

Despite extreme internal dissensions, the Dream Band lasted until early June 1944. In January 1944 the band consisted of Gail Brockman, Calvin Ladnier, and Raymond Orr (trumpets); George Hunt and J. Taylor (trombones); Nat Jones (1st alto sax); Tom Archia and Eddie Johnson (tenor saxes); Marl Young (piano, arranger); Clarence "Hog" Mason (bass—the only holdover from the old King Fleming band and from the Overton band); and Hillard Brown (drums). Ladnier and Archia had been in the Milt Larkin band when it was resident at the Rhumboogie (August 1942 to May 1943), and had returned to Chicago after the band broke up. (Our source is the Board Minutes for Local 208, January 6, 1944.) Later on Johnny Houser would replace Nat Jones as first alto. We are not sure just when he arrived, but the band soon picked up a 2nd alto player from Kansas City named Charlie Parker.

Harry Gray, the powerful president of Musicians Union Local 208, did not like Young, and insisted that veteran bandleader Carroll Dickerson (1895 - 1957) be put in as the contractor for this high-visibility job. However, Charlie Glenn had personally hired the musicians, and the band featured such unruly young talents as Charlie Parker, Tom Archia , Eddie Johnson, and Calvin Ladnier; all four resented Dickerson, whom they regarded as a fuddy-duddy, and gave him constant grief. At times the band played so loudly, supposedly inspired by Bird's example, that it antagonized patrons at the club.

One Monday morning when members of the band were playing a breakfast dance at the Club DeLisa, a few blocks away, Marl Young caught Charlie Parker surreptitiously removing Johnny Houser's music from the music stand and replacing it with his own. Young threatened to brain Parker with a Coke bottle if he didn't put Houser's music back, immediately. As Young told Walton in 1985:

It was soon after that incident that Carroll Dickerson walked out. He just couldn't take it any more. Parker and Tom Archia were running him crazy. Sometimes we would play a number with no music. This is what we called a head number. The saxes would start playing something and Tom and Parker would turn their backs and just play something altogether different.

Carroll Dickerson quit in disgust during a stormy Local 208 Board meeting on June 1, 1944, during which the entire band was chewed out by Harry Gray, and Dickerson was reprimanded for "the lack [sic] manner in which he had handled the orchestra." Marl Young was still not the candidate favored by the Union (for one thing, Charlie Glenn complained that Young would continue conversations with the other band members when it was time for him to go on the bandstand). But after two veteran band members said "No thanks" to the job offer, he finally gained acceptance as the leader. This became official when the band's new contract with the Rhumbogie was accepted and filed on July 6. Young kept Eddie Johnson, who was popular with the customers at the club, but fired Tom Archia and Charlie Parker without notice, threatening to turn in his files on them to Local 208 if they complained. Young probably replaced Parker and Archia with Nat Jones and Moses Gant; later he brought in Henderson Smith on trumpet to replace Paul King and a trumpeter named Fox to replace Calvin Ladnier; he also hired Quinn Wilson on bass, plus possibly Osie Johnson on drums. Marl Young ran the Rhumboogie house band through January 25, 1945, when Charlie Glenn replaced his aggregation with the Jeter-Pillars Orchestra from Saint Louis.

Out of Young's tenure at the Rhumboogie Cafe came his two sessions on which he led a studio band behind the club's bigest headliner, guitarist and blues singer T-Bone Walker. The first took place on October 10, 1944, while Young was still leading the house band, and 6 sides were released on the Rhumboogie label (these are also covered on our Red Saunders page). Young apparently still bore a grudge against Eddie Johnson because in the smaller studio aggregation, which featured selected members of the Rhumboogie house band along with members of Red Saunders' ensemble, Moses Gant was given the tenor sax spot in Johnson's place. Young, who was not inclined to be cooperative after Charlie Glenn quit using his band at the club in January 1945—he also didn't care for Glenn's demand to be listed as composer on some of the numbers—got into a protracted squabble with the club owner over copyrights and lead sheets from the 1944 session, delaying release of the first sides until August 1945. But the first release on Rhumboogie 4000 sold well. Reluctant to tamper with a winning formula, Glenn once again brought Young in to direct the band on a second T-Bone session, which took place on December 19, 1945. The Rhumboogie record label folded in the middle of 1946, before anything could be released from the second session, so other companies, such as Mercury, Old Swing-Master, Imperial, and Constellation were the eventual beneficiaries.

On February 18, 1946, Young was hired to take over the piano chair in the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra at the Club DeLisa (Fletcher mostly conducted at this point in his career, restricting his piano work to one or two feature numbers a night). According to Walter C. Allen's monumental book Hendersonia: The music of Fletcher Henderson and his musicians (Highland Park NJ: Walter C. Allen, 1973, pp. 439-440), the lineup when the band opened at the club was: Elisha Hanna, Matthew Rucker, Willie Wells, and Lee Trammell, trumpets; Joe Brown and Hosea Martin, trombones; Edmund Gregory and Emerson Harper, alto saxes; Woodrow Key and Otis Finch, tenor saxes; probably Buddy Conway, baritone sax; Bill Brookins, bass; and Al Williams, drums; George Floyd was the band singer. The other musicians were part of Henderson's touring ensemble; Floyd had been with him since 1942 and most of the others had joined him in Detroit in January 1945. Only Marl Young was local, hired to replace Vivian Glasby who had gotten tired of traveling with the men in the band and decided to stay in St. Louis. In April, Edmund Gregory decamped to New York, where he took up bebop and became Sahib Shihab. Emerson Harper left some months later; the altoists were replaced by Bill McCall and Hobert Clardy from the South Side talent pool. Bill Brookins' spot was quickly taken by local bassist Ellsworth Liggett. Soloing was reserved to Willie Wells (an incipient bebopper) on trumpet, Joe Brown on trombone, and the two tenor players. In August 1946 (on top of the grueling 6-night-a-week regimen at the DeLisa, he had been hitting the law books, presumably to prepare for the bar examination) Young failed to report for a show and was found asleep in his car outside the club. Although his legal training would prove useful later, Young never did get around to taking the bar examin. His replacement for the remainder of the Henderson engagement was a recent arrival from Alabama who styled himself H. Sonne Blount (he is better known today as Sun Ra).

Shortly after leaving the Henderson band, Marl Young decided to start his own record company. As early as December 1941, Marl and his brothers had opened a small recording studio, Sunbeam Recording & Music Studio, at 4448 South Michigan Avenue. When the Sunbeam label was launched five years later its address was at 6128 South Michigan. Marl Young already knew something of record company operations through his work for Rhumboogie. He expected to draw on the pool of musicians who had worked with him at the Rhumboogie, or at the Monday morning breakfast dances at the Club DeLisa. The key was finding vocalists who would attract the interest of the record-buying public, as T-Bone Walker had been able to do on his Rhumboogie sides.

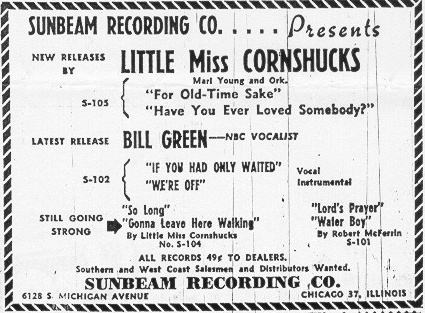

The first documentary evidence of the new company is a mention of Sunbeam 101. On November 9, 1946 Billboard announced that "Marl Young, Negro orchestra fronter, released his first waxing, Water Boy and The Lord's Prayer, by Robert McFerrin on the new Sunbeam label." Robert McFerrin, Sr., was born on March 19, 1921 in Marianna, Arkansas. He sang baritone in a gospel group, and become a local gospel soloist of some note. During World War II he served in the Army. In the 1950s he moved to New York to sing at the Metropolitan Opera. He is the father of the eclectic vocalist Bobby McFerrin, who gained fame in 1988 for his novelty song, "Don't Worry, Be Happy." Both sides of Sunbeam 101 were gospel numbers.

From a copy of Sunbeam 101 in the collection of Dan Kochakian, we learn that the accompaniment was by piano and bass only, not by one of Marl Young's larger groups. Also, the matrix numbers indicate a different session from the first Young big band outing (which McFerrin also sang on). The matrix numbers are close, however; Sunbeam 101 could have been cut a couple of days earlier.

Robert McFerrin (voc); Marl Young (p); Robert Lee "Rail" Wilson (b).

Bachman Studio, Chicago, August 1946

| 1111-S | Water Boy (arr. Avery Robinson) | Sunbeam S 101 A | |

| 1112-S | The Lord's Prayer | Sunbeam S 101 B |

Marl Young and his Orchestra would make three different sessions in the Fall of 1946. Like the Robert McFerrin session, the first two are in the 1000-1100 series also familiar to us from the session by Bing Williams on Hy-Tone; from two sessions by Rudy Richardson for Miracle; from the Robert Crum session and the first Ranch House Boys session for Gold Seal; and from a group of sessions by keyboard players in the earliest days of Rondo. They were done, a few days apart, in August 1946 at the Myron Bachman Studio on Carmen Avenue. (It definitely wasn't Sunbeam Studio—those facilities were way too modest for a big band recording.) The Robert McFerrin sides were cut right before Lil Mason's session for Rondo (matrix numbers 1113-1116).

The third Sunbeam session took place in October 1946 at Egmont Sonderling's United Broadcasting Studio. United Broadcasting, now rapidly picking up business from the indie labels, was recording sessions by Gladys Palmer with Floyd Hunt, Memphis Slim and his combo, and Brother John Sellers around this same time. Young's fourth and last session as the leader of a large ensemble, which used a string section instead of a big band, would take place at United Broadcasting in March of 1947.

The six numbers by the Marl Young Orchestra all seem to involve the same musicians, except the trombones lay out on the third session. The detailed solo credits on the original Sunbeam labels have done most of the work of identification for us: every musicians is named one place or another except the 3rd trumpeter, the 2nd trombonist, and the drummer. The late Charles Walton informed us that his drum teacher, Oliver Coleman, told him about recording with Little Miss Cornshucks for Sunbeam. Oliver Coleman was a veteran of Earl Hines' big band and had also worked in a band led by Ray Nance (before Nance left Chicago to join Duke Ellington in December 1940). After his Sunbeam sessions, Coleman would record on Eddie Johnson's studio sessions for Chess in 1951 and 1952.

Marl Young (p, dir, arr); Melvin Moore (tp); Nick Cooper (tp); unidentified (tp); Johnny Avant (tb); unidentified (tb); Nat Jones (as); Frank Derrick (as); Moses Gant (ts); Rail Wilson (b); Oliver Coleman (d); Bob McFerrin (voc).

Bachman Studio, Chicago, late August 1946

| A-1122-S | We're Off (Marl Young) | Sunbeam 102B [first version] Sunbeam 102B [second version] |

|

| 1123-S | Fascinating Lady (Marl Young-Harry Young) [BMcF voc] | Sunbeam 102A [first version] |

This session, at Bachman Studios in August 1946, immediately followed four sides by Jimmy Blade for Rondo (matrix numbers 1117-1120). It was followed, probably during the first week of September, by another Rondo session (featuring organist Elmer Ihrke, including matrix numbers 1135 through 1129).

There are two versions of Sunbeam 102. The initial coupling put the instrumental "We're Off" with McFerrin's vocal number "Fascinating Lady." This original 102 was also released in November 1946 (as mentioned in Billboard on November 16.) A second coupling of Sunbeam 102 keeps "We're Off" on Side B; the new version was advertised in Billboard in March 1947. The new A side was Bill Green's vocal number "If You Had Only Waited" (from the third session by Marl Young's Orchestra; see below).

A review of the new 102 in the March 29, 1947 issue of Billboardcriticized "We're Off" as "one of those up-tempo flag-wavers, played at such a frantic pace that solos and ensemble just don't jell." Our hopefully more judicious impression is that "We're Off" is a late Swing number trying hard to be a bebop score; it continues the aggressively modern approach that was already evident in Marl Young's arrangements for the December 19, 1945 T-Bone Walker session on Rhumboogie. Listening reveals a big band with 3 trumpets, 2 trombones, 3 reeds and rhythm. Solo credits on the labels give a major boost to researchers trying to catch up years after the fact. On "We're Off," there is a an alto solo by Nat Jones, a Hawk-like tenor outing by Moses Gant, and a bop trumpet solo by Nick Cooper. There is even a short bass solo for Rail Wilson.

"Fascinating Lady" is of course a vehicle for McFerrin's baritone crooning; it also has a piano intro by Young and a trombone statement that is probably the first appearance on record for the J. J. Johnson-style trombonist John Ivan Avant (1927 - 1988). Johnny Avant was 19 or 20 years old when this record was cut. In May 1947, he joined Red Saunders' newly enlarged band at the Club DeLisa; after gaining prominence as a steady contributor to the Saunders band, he left in 1953 and concentrated thereafter on studio work.

Just one side that we have heard from this session accords a prominent role to the drums. On "We're Off," Oliver Coleman maintains a Jo Jones-like rhythm but drops some bombs.

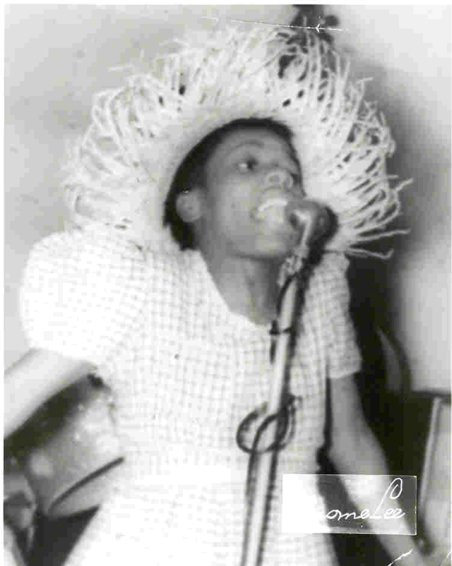

Little Miss Cornshucks was born Mildred Cummings in Dayton, Ohio, on May 26, 1923. She began performing in Ohio, but as early as 1941 she was singing at the Club DeLisa, and she appeared at the Rhumboogie Club after it opened in 1942. Her name does not appear in ads for either club during this period, but Miss Cornshucks' biographer Barry Mazor assures us, on the basis of testimony from Marl Young and other contemporaries, that she was present. She may have been doing one-off appearances as an amateur. In June 1945 Miss Cornshucks finally rated a mention in ads for the Club DeLisa. She created such a sensation that the next month she began headlining the shows, maintaining star billing through September.

Little Miss Cornshucks wore a purposely rustic outfit, wore a straw hat, came out on stage carrying a basket, and interspersed her forlorn ballads and blues with broad comedy. One of the first published comments on her act appeared in the Chicago Defender in Lou Swarz's column, "Thru Harlem" for October 6, 1945. Swarz reported, "Arthur Bryson is being offered 'heap much' for Little Miss Cornshucks to make a return engagement to a Chicago nitery... No wonder, with her act being so unique—singing those blues in that million dollar costume of a pair of 30th century bloomers and a big greasy hat... Watch the climb to stardom of Little Miss Cornshucks."

As Swarz wrote those words, Miss Cornshucks was traveling across the country, apparently tearing them up in New York City; on November 3 Swarz declared that she was "stopping every show at the Elks' Rendezvous" in Harlem (Defender, p. 16). In the spring of 1946 she would be playing again in New York and in Washington DC. Miss Cornshucks returned to Chicago in May 1946 to star at the Club DeLisa; she was in the show from May 10 through August 29, 1946, and again from September 27 through October 11 (her replacement for the remainder of that show was no less than Big Joe Turner). An August 24, 1946 photo blurb reported her headlining at the DeLisa "after a conquest of Broadway." She continued to flourish in the city, playing other Bronzeville nightspots but frequently returning to the Club DeLisa.

Marl Young had of course been backing Little Miss Cornshucks at the DeLisa during his tenure with Fletcher Henderson's band. On opening for business, he signed this exciting prospect right away. Young first recorded Miss Cornshucks in late September 1946 while she was again headlining at the Club DeLisa. Her melancholy delivery on her first release (Sunbeam 104), a bluesy rendition of the pop hit, "So Long," captured the imagination of the public. Sunbeam 104 was first advertised in Billboard on November 16, 1946. Though not a national hit, the ballad became the small label's best seller and Miss Cornshucks' signature tune. One of two Sunbeam sides to see reissue before the CD era (when Old Swing-Master brought it back out in 1949), it was a jukebox favorite in the late 1940s. "So Long" has an interesting big-band arrangement, and Frank Derrick gets an emotive alto sax break, but the Sunbeam version makes the densely scored Marl Young Orchestra an equal player. More tremulously phrased renditions, in smaller settings, were done for Coral in Los Angeles (1951) and on Miss Cornshucks' valedictory LP for Chess in Chicago (1960).

Marl Young (p, dir, arr); Melvin Moore (tp); Nick Cooper (tp); unidentified (tp); Johnny Avant (tb); unidentified (tb); Nat Jones (as); Frank Derrick (as); Moses Gant (ts); Rail Wilson (b); Oliver Coleman (d); Little Miss Cornshucks [Mildred Cummings] (voc).

Bachman Studio, Chicago, September 1946

| 1143 S | Gonna Leave Here Walkin' (Cornshucks) [LMC voc] | Sunbeam S 104 B | |

| 1144S-A | Have You Ever Loved Somebody (Marl Young-Cornshucks) [LMC voc] | Sunbeam 105 B | |

| 1145 S | So Long (Morgan-Harris-Melcher) [LMC voc] | Sunbeam S 104 A, Old Swing-Master A26 |

This session was sandwiched in between two for Rondo, an operation that was two months older and, in those days, not much bigger than Sunbeam. The organ-piano duo of Marsh McCurdy and Pauline Lamond cut a session that included matrix 1140. After the Sunbeam outing, Elmer Ihrke cut several numbers for Rondo on the Hammond organ (including matrices 1147 and 1149).

For the B side of Sunbeam 104, Young selected "Gonna Leave Here Walkin'," a 12-bar blues with typical brassy showband riffing. We are reasonably sure that this number was in her repertoire at the Club DeLisa. The break features the leader at the piano.

The other known side from this session was used on Sunbeam 105. Marl Young advertised Miss Cornshucks' second record in the March 22, 1947 Defender. he copy boasted that "For Old Time's Sake" (the other side of Sunbeam 105, from the third session; see below) it was "Her Greatest Hit Since 'So Long'." (Well, OK; she hadn't released anything else.) "Have You Ever Loved Somebody?" features more of the bebop incursions that were characteristic of Marl Young's band at this period; the alto solo on this number belongs to Frank Derrick.

Miss Cornshucks was brought right back for the Marl Young Orchestra's third session in October. Like several other independent labels, Sunbeam was now starting to use the United Broadcasting studios.

Alongside Sunbeam 105, the company's ad in the March 22, 1947 Defender, plugged a release by William "Bill" Green, described as NBC's newest star, on a second edition of Sunbeam 102. The instrumental, "We're Off," from the first session, was still the B side. The ad gave the only address we have for the company, 6128 Michigan Avenue. In its March 29 issue, Billboard gave Miss Cornshucks and "Have You Ever Loved Somebody" a favorable review. However, the Bill Green vocal on the new 102 was considered "too classical a handling." "If You Had Only Waited" is a sappy ballad sung by Bill Green in a very sweet near-falsetto. It includes a solo by altoist Frank Derrick which, again, is duly credited on the label.

If Bill Green made any other sides for Sunbeam, we've found no trace of them.

Marl Young (p, dir, arr); Melvin Moore (tp); Nick Cooper (tp); unidentified (tp); Nat Jones (cl -1, as); Frank Derrick (cl -1, as); Moses Gant (bcl -1, ts); Rail Wilson (b); Oliver Coleman (d); Bill Green (voc); Little Miss Cornshucks [Mildred Cummings] (voc).

United Broadcasting Studio, Chicago, October 1946

| UB 2674S | If You Had Only Waited [BG voc]^ | Sunbeam 102A [second version] | |

| UB 2675 A S | For Old Time's Sake (Harry Young-Marl Young) [LMC voc] | Sunbeam 105 A, Old Swing-Master B26 | |

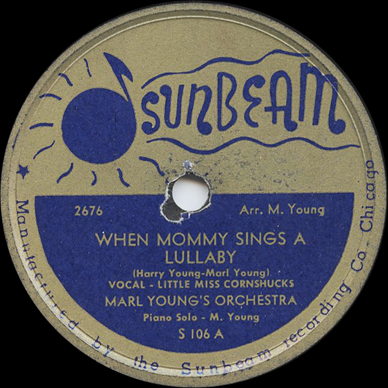

| UB 2676-S | When Mommy Sings a Lullaby (Harry Young-Marl Young) -1 [LMC voc] | Sunbeam 106 A | |

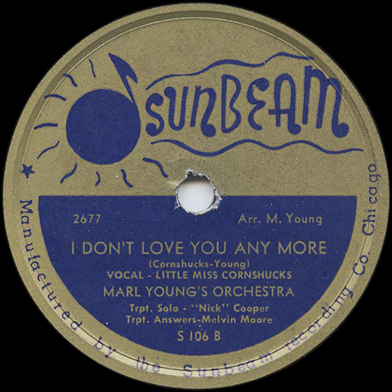

| UB 2677-S | I Don't Love You Any More (Cornshucks-Young) [LMC voc] | Sunbeam 106 B |

The band here sounds like the group that made the first two sessions, except no trombones are audible. The muted trumpet lead on "Old Time's Sake" is by Melvin Moore. Thanks to Tom Kelly, we have been able to hear Sunbeam 106 and see the label copy. "When Mommy Sings a Lullaby" is an atmospheric original ballad by Marl and Harry Young that uses muted trumpets and clarinets à la "Mood Indigo." The trio of two clarinets and bass clarinet switches back to two alto saxes and a tenor during the arrangement, and the only solo is by the composer on piano. "I Don't Love You Any More" credits Nick Cooper with the trumpet solo, a fierce emulation of Dizzy Gillespie; the brass section plays several bop licks during this blues arrangement. Toward the end of the piece, Little Miss Cornshucks trades phrases with Melvin Moore, who is duly credited on the label with "Trpt. Answers."

These sides were cut not long after Memphis Slim's first session for Miracle, which we estimate took place in October 1946. We've estimated recording dates for the UB2000 matrix series on the assumption that UB2999 turned over to UB21000 around January 1, 1947.

An item in the Chicago Defender, June 7, 1947, had Miss Cornshucks appearing at the Frolics Bar after several months performing in New York. The tone assumed she was a nationally known star. Through 1947 and 1948, when not headlining major venues in Chicago, such as the Savoy Ballroom, the Beige Room in the Pershing Hotel, and the Club DeLisa, she toured across the country.

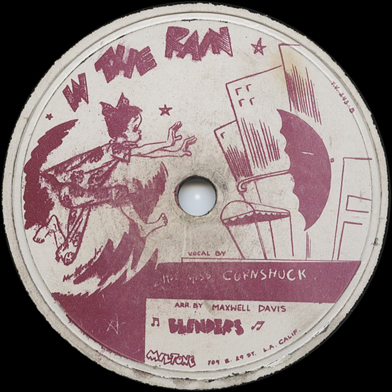

Her Sunbeam contract probably expired in September 1947. Making her debut in Los Angeles in early November (her first week at the Last Word Café was covered in the Los Angeles Sentinel, November 6, 1947, p. 21, which duly mentioned that "So Long" stopped the show), Little Miss Cornshucks promptly made some new records for Roy Milton's Miltone label. Really promptly—"Keep Your Hand on Your Heart" (Miltone 242) was listed as the #9 tune on East Los Angeles jukeboxes one week later (Los Angeles Sentinel, November 13, 1947, p. 21). Gene Phipps led the house band at the Last Word, but on her Miltones she was accompanied by Maxwell Davis's Blenders. Eventually, she would have three singles on Miltone: 242, 243, and 246 (see http://koti.mbnet.fi/flidi/milton/). Miltone 243 was advertised by a Chicago distributor in Billboard on February 28, 1948; 242 and 243 were advertised in the same trade paper by a distributor from Detroit on April 3, 1948. (We have included the renowned cartoon labels to Miltone 243 on our page because they portray Miss Cornshucks' stage persona so well. Our thanks to Marv Goldberg for pointing out that the Miltones were not made in early 1948, as stated in previous discographies.)

Miss Cornshucks ended her run in Los Angeles in mid-December 1947. Besides her work at the Last Word, she enjoyed a guest appearance at Billy Berg's and a week's run at the Million Dollar Theatre. She also supposedly had a bit part in a Monogram picture, "Death on the Downbeat" (if so, the picture went unreleased). She left LA to fulfill a booking at the Frolic Show Bar in Detroit, starting December 19 ("Miss Cornshucks Leaves W. Coast," Pittsburgh Courier, December 20, 1947, p. 16). She was back in Chicago in May 1948 for a run in a produced show at the Beige Room; Lonnie Simmons led the house band (Chicago Defender, May 1, 1948, p. 8). In June she was at the Club Astoria in Baltimore with the Teddy Brannon Trio (Baltimore Afro-American, June 19, 1948, p. 6). In 1948 she also made major tours of the West Coast and the South. She was in Chicago again for the holiday season, appearing at Club Silhouette with Dick Davis's Combo (Chicago Defender, December 25, 1948, p. 16).

"So Long," from her first session for Sunbeam, was reissued in the summer of 1949 on the Old Swing-Master label, which had inherited her Sunbeam masters; on this occasion it was given a new coupling, "For Old Time's Sake" from her second session. Miss Cornshucks went on to record in Los Angeles for Aladdin in August 1949. In September, she signed with Decca (Los Angeles Sentinel, September 29, 1949, p. B6; the story stated that "She is at present making her home in California"). Her next session would be for Decca's Coral subsidiary in February 1950.

She was sidelined by illness for a time (reported to be in the hospital in J. T. Gipson's column, Los Angeles Sentinel, March 9, 1950, p. B2). At her second and last session for Coral in 1951, Miss Cornshucks recorded her greatest version of "So Long" and a sublime rendition of "Try a Little Tenderness." After that, she essentially ended her national touring, making her home in Kenosha, Wisconsin and living under her married name, Mildred Jorman (her married name appeared in the Local 208 Board Minutes for August 4, 1949, when the Board heard out Marl Young's claim against her for $60 that may have been left over from her Sunbeam days).

Her level of activity in the Chicago clubs was variable, but in 1956 and 1957 Little Miss Cornshucks could be heard with some regularity at such establishments as Budland (where King Kolax backed her in August 1956 and Sun Ra's Arkestra accompanied her in October and November of the same year). In 1960 she made a remarkable LP for Chess Records, which showed that she had kept up with the development of soul music; sadly, it was her last recording and she landed few paying gigs on the strength of it. She died in utter obscurity in Indianapolis on November 11, 1999.

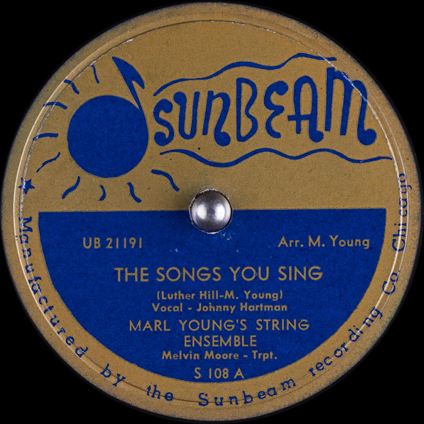

Next in Sunbeam's run came a session that has never been mentioned in a discography before. We are indebted to Art Zimmerman for information about Sunbeam 108, the debut on record for singer Johnny Hartman. The biographies on Hartman have always assumed that the sides he recorded with Earl Hines in November 1947 were his first.

Singer Johnny Hartman was born July 13, 1923, in Chicago. Hartman got his start in church, and always claimed that Ruth Jones (Dinah Washington) played piano behind him. He was a product of the DuSable High music program, in which he sang with the school's glee club and with the resident dance band under the direction of Walter Dyett. His breakthrough as a professional singer took place in 1946, when he won an amateur contest at El Grotto, as the basement club in the Pershing Hotel was then named. The prize was $25 and a week performing with the house band, Earl Hines and his Orchestra. The stay lasted several months, and El Grotto advertised him as "Chicago's Newest Bronze Sinatra." Hartman was primarily a ballad singer who concentrated on standards, but because of his color he was categorized as a "jazz singer." Marl Young heard and recruited Hartman while he was still at El Grotto. We have not heard these sides, but Hartman was a remarkably consistent performer: no matter who he was recording for he employed his resonant baritone to make every number smooth, soothing, and laid back. Sometimes, however, his proudly "cool" approach veered into stiffness.

Not long after recording these sides, Johnny Hartman moved over to the fading Rhumboogie Club, where the headliner was singer Sarah Vaughan. Beginning on March 27, the revue ran until the Rhumboogie closed its doors in mid-May. Toward the end of the year, Hartman went on tour with Earl Hines, recording with him in November 1947 and again for Sunrise in New York in December; see our Miracle page for more about the Sunrise sessions. After his Hines recordings, Hartman toured and recorded with the Dizzy Gillespie band (for RCA Victor in 1949), followed by stays at Mercury (1949), Apollo (1950), and RCA Victor (1951 - 52). His breakthrough to critical acclaim came in 1956 with his first LP, Songs from the Heart on Bethlehem. Hartman recorded many more albums, five of them with producer Bob Thiele (for Impulse! and ABC). One of the Impulses was a notable session with John Coltrane. Hartman continued to record up to 1980. He died on September 15, 1983.

Sources on Hartman: "El Grotto Find," Chicago Defender, 7 September 1946; El Grotto ad, Chicago Defender, 25 January 1947; George T. Simon, "Executive Singer," Metronome, December 1949, p. 18; Will Friedwald, "Johnny Hartman, 1923-1983: An Appreciation," liner notes, The Johnny Hartman Collection 1947-1972 (Universal City, Cal.: Hip-O, 1998).

Marl Young (p, dir); Melvin Moore (tp); other musicians unidentified; Johnny Hartman (voc).

United Broadcasting Studios, Chicago, c. February 1947

| UB 21191S-1 | The Songs You Sing (Luther Hill-M. Young) | Sunbeam 108 A | |

| UB 21190S-1 | Always To-gether (Evelyn Washington) | Sunbeam 108 B |

Our information on this release came from Art Zimmerman. Photos of the label (now available at the Internet Archive, archive.org) show that Melvin Moore was featured on trumpet on both sides, that Marl Young was responsible for the arrangements, and that Young cowrote one of the tunes. Billboard reported on March 22, 1947 that "John Hartman and Viola Jefferson, singers" had been signed by Sunbeam. If Sunbeam got around to recording Viola Jefferson (at this session or a different one), nothing was ever released.

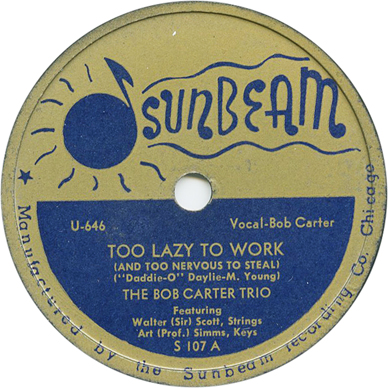

Young also scouted and recorded Bob Carter, a bassist who headlined one of the piano trios then popular in Chicago clubs. Carter's bandmates at the time were "Professor" Art Simms on piano and "Sir" Walter Scott on guitar. (Among the other many other active trios using the same instrumentation during this period were those of Robert "Prince" Cooper and Jimmy Bell, who recorded for Aristocrat; Edward "Duke" Groner, who recorded for Ebony and Aristocrat; Loumell Morgan, who worked frequently in Chicago but made his records in New York; plus of course the Big Three Trio with Willie Dixon and Leonard "Baby Doo" Caston, which had a longstanding relationship with Columbia and OKeh.)

Robert James Carter was born in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1917. He moved to Chicago as an adult, and served in the US Army during World War II.

Bob Carter surfaced on the Chicago scene in 1945. His contract for two weeks at the Circle Inn (where he replaced a Buster Bennett trio featuring Buster on piano) was accepted and filed by Musicians Union Local 208 on January 18 of that year. The next month he moved to the DuSable Lounge; his 2-week contract with an option was accepted and filed on February 15. On November 1, he posted an indefinite contract with the Hurricane Lounge; on December 20, two weeks at the Vogue Lounge (followed by another 2-week contract on January 3, 1946). He filed more two-week contracts with the Vogue Lounge on March 7 and March 21; on April 18 and May 2, he posted two-week contracts with the Music Box. On June 6, 1946, Local 208 accepted and filed another two week contract with the Vogue Lounge; it was followed by a 4-week contract (posted on June 20), and more for 2 weeks each (accepted and filed on July 3 and 18 and August 15). The Carter trio moved to the Last Chance Lounge (indefinite contract posted on August 15). On September 14 of that year a Defender ad for the Wonder Bar (544 East 63rd Street) billed the Bob Carter Trio (8-week contract posted on September 5).

Bob Carter recorded for the first time on October 4, 1946, when he and his trio-mates Art Simms and Walter Scott joined in the second of two blues-oriented sessions Specialty Records was conducting in Chicago with Jump Jackson as the leader (see our Sax Mallard page for session details.) Carter drew the vocal assignments for both sides of Specialty 506 and both sides of 509. After the recording session, Carter, Simms, and Scott continued their run at the Wonder Inn (as the joint was sometimes identified) with another 8-week contract (posted with Local 208 on November 7). On November 8, 1946, Bob Carter copyrighted three songs, perhaps anticipating a recording session that fell through. Obviously the trio had developed some staying power with the Wonder Bar's clientele, because their stay was extended for another 4 months (contract filed on January 2, 1947). The trio's session for Sunbeam took place during their run at the Wonder Bar.

Bob Carter (b, voc); "Prof" Art Simms (p); "Sir" Walter Scott (eg).

Universal Recording Chicago, around March 12, 1947

| U-646-IV | Too Lazy to Work (And Too Nervous to Steal) (Daylie-Young) | Sunbeam S 107 A | |

| U-647-IV | Bonus Blues (Carter) | Sunbeam S 107 B | |

| Hey Now (Carter) | [Sunbeam 109 A] | ||

| Get a Gal of Your Own | [Sunbeam 109 B] |

The Bob Carter Sunbeam 107 was listed among the new releases in Billboard for May 17, 1947. The matrix numbers on Sunbeam 107 nail down the location and approximate recording date as Universal Recording and March 1947. The IV suffix to the matrix numbers can be seen in the shellac but not on the label. Meanwhile, Bob Carter copyrighted "Bonus Blues" and "Hey Now" on March 12, 1947 (our thanks to Barbara Berry for copies of his copyright forms).

Universal had recently expanded its business to include commercial recordings for the indie labels. The Bob Carter session for Sunbeam took place a little after two sessions by Jerry Murad's Harmonicats, which would be used to lauch the new Vitacoustic label, and shortly before another Vitacoustic session by pianist Mel Henke. The first session for a more durable new label called Aristocrat would follow in April.

"Too Lazy to Work," an ironic tribute to the unemployed, ill-dressed man, is a breezy, swinging number in the Nat King Cole tradition. Marl Young collaborated with Holmes "Daddy-O" Daylie, a prominent DJ, on the tune; they were also responsible for a song called "Hip Little Mouse" that apparently went unrecorded. "Too Lazy" was revived by the extremely obscure Glo Tone label. Glo Tone made one session at United Broadcasting, in the second half of 1948 or the beginning of 1949; "Too Lazy" was sung by Joe Williams (soon to become the band singer for Jay Burkhart's orchestra, then for Red Saunders). Williams was accompanied by a big band led by trumpeter Melvin Moore, who had been on four sessions for Sunbeam. Moore owned the label; inquiring minds want to know who wrote the arrangements for the session. In Los Angeles, Young would revive "Too Lazy" for a September 1950 T-Bone Walker session for Imperial on which he served as pianist and arranger. (Marl Young's interview with Dan Kochakian in Blues and Rhythm 179 refers to a session in Chicago on which Young recorded "Too Lazy" with horns; was he really thinking about the Glo Tone?)

"Bonus Blues" (Carter's composition) is an urbane 12-bar number about the domestic worries of a returning GI. There is good execution by the trio members, but in our opinion Carter's rather whiny vocal quality was better suited to the comic items.

Bo Sandell, in "The Sunbeam Story," Blues & Rhythm, June 1999, listed a second Bob Carter release on Sunbeam 109. Granted that all Sunbeams 78s are rare, we have never seen or heard a copy of Sunbeam 109 since we put up the first version of this web page. It looks as though 109 was a planned release that never emerged.

During April 1947, the Carter Trio took up at the Hurricane Lounge (4-week contract filed April 17). They traded places with Tommy Dean's combo in early May, picking up 5 days at the Music Box (contract posted with Local 208 on May 1), which they soon extended with an "indefinite" contract (posted June 5). After a long stretch at the Music Box, the Carter Trio showed up briefly at El Casino (contract for 3 days only, filed October 2, 1947). On October 16, Carter filed a new "indefinite" contract with the Music Box.

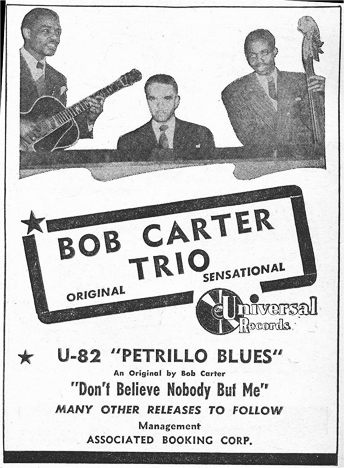

Carter obtained a release from Sunbeam on November 16, 1947; it was among Marl Young's last official acts as proprietor. By this date, it was generally known that American Federation of Musicians President James C. Petrillo had announced a recording ban, to begin January 1, 1948. At some point during the last six weeks of 1947, the Carter trio cut eight sides for the Universal label. Universal was an enterprise oriented toward pop, Country, and an occasional polka. It recorded little jazz, and even less jazz by black musicians. However, Bill Putnam, who ran the label from September 1947 through the end of 1950 as a spinoff of his Universal Recording operation, knew Bob Carter and his trio from recording them for Sunbeam. The new release, "Petrillo Blues" b/w "Don't Believe Nobody but Me," on Universal U-82, appeared in January 1948 and was advertised in Billboard on January 24. The two tunes were copyrighted by Bob Carter on January 19, 1948.

The Universal got a lukewarm review in Billboard on February 14, 1948, mainly on account of "Petrillo Blues": "The 'Boss' may consider this a dubious honor. Sounds like [Robert] Taft had a hand with lyrics" (p. 31). Petrillo was still smarting over the recent passage of the Taft-Hartley Act, which reduced the power of unions like his own. Working musicians may have had a different opinion of the song.

The trio probably remained at the Music Box until the end of that month; Carter filed a contract for 1 week at the Blue Heaven Lounge on February 5, 1948. After that the trio appears to have gone on the road for a while, but in May 1948 they reappeared in Chicago, doing a series of 3-day weekends at the Saratoga Lounge (contracts posted May 20, July 1, July 15, August 5; on August 5 and September 2 Walter Scott filed 3-day contracts with the same club in his own name, which may or not have involved Carter.) The Defender of October 9, 1948 ran an ad for the Bob Carter Trio at the New Hollywood Rendezvous (3849 Indiana Avenue). There he was identified as "Sunbeam Recording Artist, A trio which has become one of the nation's Outstanding Playing your favorite tunes." (The contract was filed on October 7.)

On January 8, 1949, a Defender ad placed by the Blue Dahlia at 425 East 43rd Street headlined the Bob Carter Trio, "Recorder of 'Too Lazy to Work'" (contract for 4 weeks filed on January 6). After 3 nights at the Flamingo Lounge, the trio moved to the Saratoga Lounge for about a month (both contracts posted with Local 208 on February 3). On March 3, Carter's indefinite contract with the Music Box was accepted and filed.

Bill Putnam and Bernie Clapper of Universal Recording did not record Carter again. They also sat on the other six sides that Carter had made at the end of 1947. After being approached by another label, Bob Carter got a release from Bill Putnam on April 13, 1948. Unfortunately, it appears the other record deal fell through. There was talk, toward the end of 1948, of a "Double Feature" release on Bob Carter; a "Double Feature" was a 78 rpm EP (two tracks per side) that Universal had developed. Four tracks from the end of 1947 would have been used, but we've never seen a copy of this particular Double Feature.

On May 19, 1949, Robert James Carter posted another 3-day contract with the Flamingo Lounge. Bob Carter dropped off Local 208's contract lists for an extended period after August 18, 1949, when he posted a 2-week contract with the Music Box. During at least part of this time he was working in Chicago as a sideman.

Somebody named Bob Carter ended up recording two singles for a very small operation called Rim, whose business address was 500 East 63rd Street. This Bob Carter led a sextet, consisting of Nick Cooper, trumpet; Porter Kilbert, alto sax; Arthur "Swing Lee" O'Neil, tenor sax; Art Simms, piano; Curt Ferguson, bass; and E. Miller, drums. We'd thought that the leader on this session was a different person, because Robert James Carter would have played the bass himself. But the presence of Art Simms makes us wonder whether Robert James Carter was a non-playing leader on this occasion. Rim 100 used the band behind singer Rudy Richardson (who had recorded for Miracle in 1946) on "If You Get It" and "You Made My Heart Cry Out." Rim 101 coupled Richardson's singing on "Write Me a Letter," obvously a cover of the hit version by the Ravens, with an instrumental performance of "Burton's Bounce." We'd like to say more about these sides, but apart from a Central Record Sales ad in the Chicago Defender, June 25, 1949, and the label copy, there is not one scrap of documentation on them. (Central Record Sales, at 500 East 63rd Street, was the distributor for Miracle Records, at the same address. What this says about the ownership of Rim we don't know.) Rim 100 turned up in a John Tefteller auction in 2009. Rim 101 was in the collection of Bill Sabis and is now in the collection of Robert L. Campbell.

Bob Carter reappeared in town as a leader in 1953, when he posted an indefinite contract with the Rose Bowl Casino (accepted and filed on March 19). On June 18, 1953, he filed an extension to the Rose Bowl contract.

The run at the Rose Bowl Casino started just in time for another Bob Carter ork to record for the extraordinarly obscure Cool label. As far as we can determine, all 8 sides intended for release on Cool were cut at one session in March 1953 (the first announcement of recordings by Cool's parent company, Co-Ben, appeared in Billboard on March 28, 1953). Then there was some delay before a name was chosen for the label and Cool 101/102 emerged in July. Just four of the sides saw release before the label folded in October. Cool 101/102 featured a singer named Herbert Beard, who never recorded for anyone else. Cool 103 was the first single for blues harmonica player Billy Boy Arnold, then 17 years old. The band consisted of tenor saxophone, piano, electric guitar, bass, and drums. The only band member named in Fancourt and McGrath is Curt Ferguson. We don't know where this identification came from; we figured that Robert James Carter, then leading a combo at the Rose Bowl, played bass on the Cool recordings. As The Blues Dream of Billy Boy Arnold (written with Kim Field, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021) flatly declares, "Bob Carter was the bass player on the session" (p. 89).

Still at the Rose Bowl, Bob Carter filed another indefinite contract on July 1, 1954. Around this time, Bob and his sister Ann, who had recently recorded for Blue Lake, acquired an agent in Southern California. Ann Carter made an appearance in Los Angeles, but whether the signing led to any gigs for Bob Carter there is unknown. Bob Carter began to work less regularly in music during this period, eventually taking a day job at the Post Office. He showed up just one more time on 208's contract list on May 21, 1959, when he filed a two-week contract with Oddo's Lounge (an establishment that in those days was booking Sax Mallard, among others). For some time after that he was a regular member of Lorenzo Smith's R&B combo, which played one-nighters and weekend engagements around the state of Illinois. According to Barbara Berry, Bob Carter became less involved in music after his mother died in 1968. Bob Eagle has reported that Robert J. Carter, who played the "bass violin," was still an active member of Local 10-208 in 1985. Bob Carter died in 2001.

Confusion has arisen because there were at least two Bob Carters on the scene in Chicago. The second Bob Carter, a White pianist, was the subject of Sharon A. Pease's column in Down Beat on June 2, 1946. This Bob Carter was born in Baltimore, Maryland, around 1920 (he said he was 26), and later moved with his parents to Millville, New Jersey. As a youth he took formal lessons in piano and sax. He listed his influences as Teddy Wilson and Art Tatum. By the early 1940s he was heading his own combos at seaside resorts in New Jersey. From 1942 to 1946 he served in the Army in the South Pacific. Just after his release in early 1946, he joined the Jack Teagarden Orchestra, and was still working with Teagarden when he was interviewed (in fact, Carter recorded one session in Chicago with the Teagarden band, for Teagarden Presents). Pease would regularly feature a piano composition by his interviewee, and Carter's was a slow blues. At one time we stated, incorrectly, that the white Bob Carter was responsible for the Universal release; this was before we saw Universal's ad for the record.

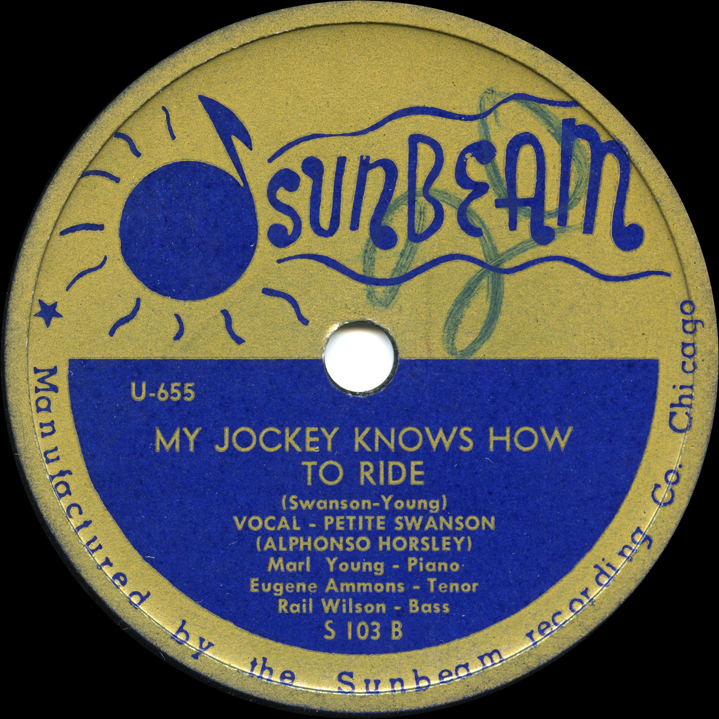

The same day as the Bob Carter Trio session, or very soon thereafter, Marl Young recorded with his own trio behind vocalist Petite Swanson. Petite Swanson was a member of Valda Gray's troupe of female impersonators, who for much of the 1940s were the main attraction at Joe's Deluxe Club in Chicago; Marl Young had led the band there in 1943. Some of the entertainment at Joe's Deluxe is preserved on the recordings made by two of the house band leaders: Dallas Bartley's session for Cosmo and his three soundies from 1945, and Bill Martin's 1946 sessions for Hy-Tone (although Martin used a studio lineup instead of the musicians he was appearing with nightly). The Swanson session includes the only surviving performances by a member of the Gray troupe. Referring to him as a "fem impersonator," Billboard announced in its March 22, 1947 issue that Swanson had just been signed to the label. The way indie labels did their business, we infer from this that Swanson had already recorded. In his article on the label in Blues & Rhythm, Bo Sandell gives La Swanson's real name as Alphonso Horsley. In its March 1948 issue, Ebony magazine ran an article on the female impersonators at Joe's Deluxe Club. Petite Swanson is mentioned as a regular performer there; Ebony spells Alphonso's last name as "Hersley" and states that he was 40 years old at the time, a former school teacher who "attends Catholic church quite regularly." According to the Ebony writer, he was a "topnotch blues singer but favorite song is Schubert's 'Serenade'."

Not everyone appeared to understand Petite Swanson's act. In 1945, a young Marshall Stearns, in from New York, decided to take in Dallas Bartley's six-piece group at Joe's Deluxe Club, and wrote a rave review of Bartley's band—which then included Bartley on bass, Mac Easton on alto sax, Reese Thomas on tenor, and Bob Hall on trumpet (the other two were unnamed)—hailing their music as "real jazz." He was also thrilled by Swanson, writing, "Highlight of the floor show is a blues singer named Petite Swanson, whose idols are Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith. When Petite backs away from the mike and lets go with 'Evil Gal Blues,' put up on what she's putting down! She has the power and tone of the old-time, great blues singers and she knows the style by instinct." Nothing in Stearns' report indicates that he was watching a female impersonator floor show, or that the sources of Ms. Swanson's power and tone included some testosterone! In any case, he knew the jazz was real. See M. W. Stearns, "Dallas Bartley Pleases Those in Search of Jazz," Down Beat, 15 September 1945, p. 2.

Marl Young had no investment in keeping secrets—he put Swanson's real name right on the label.

Swanson's release on Sunbeam 103 obviously followed the repackaging of Sunbeam 102 (see above; if a Sunbeam 103 had been planned previously, it left no trace). Sunbeam 103 is very rare; the main lure for today's listener would be the appearance by the young Gene Ammons—but even Jug's presence has so far failed to spur any reissues.

The second release, mentioned in Sandell's article, was supposedly on Sunbeam 107. This would have stepped on Bob Carter's single, also numbered 107. We figure a second Swanson 78 was planned, but replaced with Bob Carter's Sunbeam 107. The highest numbered Sunbeam that we have seen or heard was Sunbeam 108 (see above). We've seen Carter's Sunbeam 107 with our own eyes, but not Swanson's.

Petite Swanson [Alphonso Horsley] (voc); Marl Young (p, arr); Gene Ammons (ts); Rail Wilson (b).

Universal Recording, Chicago, March 1947

| U-654-IV | Lawdy Miss Claudy (L. Williams-Young) | Sunbeam S 103 A | |

| U-655-IV | My Jockey Knows How to Ride (Swanson-Young) | Sunbeam S 103 B | |

| I'm Sorry | [Sunbeam 107 A] | ||

| Did You Ever Feel Lucky | [Sunbeam 107 B] |

Again, see Bo Sandell, "The Sunbeam Story," Blues & Rhythm, June 1999. As with Bob Carter's 107, the matrix numbers on 103 carry an IV suffix in the trail-off shellac. Each also carries an RX1 incised in the shellac, indicating a remastering.

The Petite Swanson session in March was the company's last. Mentions in the trade papers ceased after May 17, which probably marked the end of Sunbeam's releases. A Billboard item from May 24 alluded to the company, but its main point was that Marl Young was writing the libretto for a revue to benefit the YMCA in Chicago. In September, Marl Young and his brothers signed a deal with the Vitacoustic label to reissue Sunbeam material. The deal was announced in Billboard on September 27, 1947 (although the periodical reported it incorrectly, as though Vitacoustic was contracting to record new material by Marl Young and his Orchestra). Vitacoustic filed for bankruptcy at the end of February 1948, before it had gotten around to releasing anything it had acquired from Sunbeam.

Some of the Sunbeam masters were then impounded by Egmont Sonderling of United Broadcasting Studios, along with a bunch of newly recorded Vitacoustic masters that he hadn't been paid for. In January 1949, after unsuccessful attempts had been made to auction off the other remants of Vitacoustic, Sonderling started the Old Swing-Master label with DJ Al Benson to recoup some of his money, and that is how the 1949 reissue of Miss Cornshucks came about. What happened to the rest of the Sunbeam masters is not known (for instance, the Vitacoustic deal might not have included the Bob Carters, which Marl Young did not play on).

Marl Young no longer had a record label to look after. On November 16, 1947, he and the company's secretary Silas Purnell signed a release for Bob Carter, as noted above. This was a formality; they were closing up shop. Free to leave, Marl Young departed a few days later for Los Angeles, where he thought he would be replacing Wild Bill Davis in the Louis Jordan band (Davis, in turn, was moving his base of operations back to Chicago, where he worked with Claude McLin and Buster Bennett before setting up his own organ trio). Unfortunately, Jordan was in such a hurry to get more recordings made that he began working with Bill Doggett shortly before Young got to LA. Doggett would hold onto that Jordan gig through 1950. The snafu did no harm to Marl Young, who established a popular trio and had no trouble ensconcing himself in the West Coast music scene.

He became prominent in the Musicians Union in the early 1950s, helping to integrate the segregated Union locals in LA. He worked with Buddy Collette, Bill Douglass, and Benny Carter, among others, to merge Local 767 and Local 47, writing the merger proposal himself. The merger became official on April 1, 1953, more than a decade before the segregated locals would come together in Chicago. In 1957, Young became the first black member of the Local 47 Board.

In 1958, Marl Young accompanied singer Marilyn Lovell when she auditioned for a spot in Lucille Ball's Desilu Workshop Theater; in 1959, he started doing arrangements for the theater. He began working as the pianist in the warm-up band for the Lucille Ball Show in 1962 and after taking gradually increased responsibilities for the music on the show, he finished on Here's Lucy, from 1970 through 1974, as the music director. While music director, he hired two musicians who had been in the bands at the Rhumboogie, John "Streamline" Ewing (trombone) and Melvin Moore (trumpet).

In 1974, Marl Young was elected Secretary of Local 47, a position that he held for 8 years. He drafted many of the current by-laws of the Union local, and served on the California Arts Council. He finished his last term on the Board in 2008, at the age of 91. He died in Los Angeles on April 29, 2009 from complications of prostate cancer. He was survived by a son, a granddaughter, and a great-grandson.

Robert L. "Rail" Wilson was Marl Young's go-to bassist in 1946 and 1947, appearing on 5 of Sunbeam's sessions. Meanwhile, Wilson and Oliver Coleman also recorded with pianist Dorothy Donegan, for Continental in October 1946. Rail Wilson was born in Macon, Georgia, probably in 1919. His family moved to Chicago, where attended DuSable High School and trained under Captain Walter Dyett. He was active on the scene after World War II, performing with Dinah Washington and Ben Webster. Wilson kept performing for more than 30 years after Sunbeam closed. In 1960, he was a member of the King Fleming Trio, appearing on Fleming's first LP for Argo. Later, Wilson recorded with 1920s-style pianist Art Hodes. Rail Wilson died at Ingalls Memorial Hospital in Harvey, Illinois, on December 6, 1978. He was 59 years old ("Chicago jazz musician Robert L. Wilson dies," Chicago Tribune, December 7, 1978, p. 67).

Sunbeam was a little company. Managing 9 releases, if we count both versions of Sunbeam 102, over the space of a year, it would have to be judged a failure. Among its contemporaries, Hy-Tone failed to register a hit, but lasted more than twice as long; Vitacoustic scored a monster hit (though it couldn't sustain itself beyond that); Miracle lasted nearly 4 years and produced a string of hits; and Aristocrat hung on and grew into Chess Records. The recording quality on the Sunbeam sides was good for the period, and the pressings we have seen were pretty clean (many 78s issued by indies in the immediate post-WWII period, when records were still made of shellac and filler, are cloudy or pimply and afflicted with excess noise). The distinctive blue and gold Sunbeam labels still catch the eye today. At least the sides by Little Miss Cornshucks had hit potential.

But small labels had a substantially tougher time than the major turning a record into a hit; they had much smaller promotional budgets to work with, and were dependent on a variety of independent distributors and independent promotion men, some less reliable than others. We will give the founder the last word:

Possibly, if I had a larger company, the records would have done better. The records did well, but they still didn't do as well as they should have, maybe because of the fact that we were not RCA or Capitol or one of the big companies. (Marl Young, interviewed by Charles Walton in 1985)

As with so many of the post-WWII independents, there has never been a coordinated reissue of Sunbeam material. Still, the CD on Classics that includes all of Little Miss Cornshucks' sides for the label was an encouraging development. We would appreciate any help that collectors can give us in filling in the gaps in our presentation.

We are indebted to the late Charles Walton for the Bronzeville Conversation article, "Marl Young, activist musician and the first Black music director of a network television show," which is based on his 1985 interview with Young. Dan Kochakian's 2002 interview with Young, published as "The Marl Young Story" in Blues and Rhythm 179, 16-20, is a valuable source of material on Young's early career and some aspects of his effort at Sunbeam (though Young apparently forgot the Bob Carter session); in addition, Dan provided us with scans of rare 78s from his collection. For Marl Young's obituary, we are indebted to Thomas Palmer, who sent us a copy of the Local 47 Newsletter commemorating his death. We also consulted Dennis McLellan, "Marl Young dies at 93; Pianist was key in desegregating L.A. musicians unions," Los Angeles Times, May 3, 2009. We extend further thanks to the late Otto Flückiger, the late Eric LeBlanc, Tom Kelly, the late George Paulus, Bo Sandell, Mario Schneeberger, Art Zimmerman, Steve Cushing, Bill Daniels, and Barbara Berry.

Back to the Red Saunders Research Foundation page.

Back to Robert Campbell's home page.