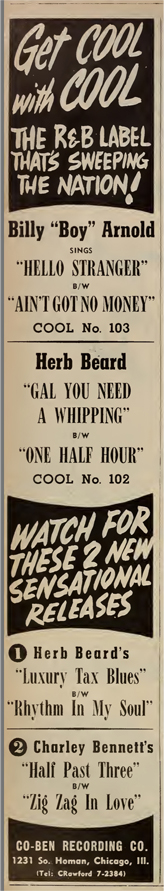

Revision note: The publication of Billy Boy Arnold's autobiography (The Blues Dream of Billy Boy Arnold, by Billy Boy Arnold and Kim Field, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021) has finally given us a little more to work with. Our thanks to Kenneth Voss for alerting us to the book. Arnold's reminiscences about making a record for Cool are detailed and in some cases verify had been mere conjecture (we weren't sufficiently confident that the session took place at RCA Victor Studios to put it in the page, but Arnold has a vivid recollection of the location and the engineer). Arnold's account also explains who he had in mind to play on the session (it wasn't Ellas McDaniel's group) and how Bob Carter's group ended up there instead. Our thanks to Marv Goldberg for turning up two notices about the Co-Ben company before it had settled on Cool as the name for its label. With the rediscovery of a solitary ad in Cash Box (September 19, 1953, p. 18), Dan Kochakian has doubled Cool's known output (from 4 sides to 8). However, the 4 "new" sides that were announced in that ad were never released, so far as we can determine. And a 2017 CD release (a 5 CD set on Wienerworld 5100) finally includes both Billy Boy Arnold tracks from Cool, as does a 2018 CD titled Windy City Dandies. Our thanks to Bob Eagle for a biographical sketch on the label's co-owner, Collenane Cosey; to Steve Cushing for more about Mrs. Cosey; to Dave Penny, Mark Sinclair Harris, and Stefan Wirz for help with the (super sparse) reissues—and to Dr. Robert Stallworth for a scan of a real live Cool 45.

Cool was among the tiniest of Chicago independents. It was in business for six or seven months. So far as we can determine, it conducted one recording session. There were two releases. Two further prospective releases never got past the announcement stage. The company nonetheless helped to launch the career of harmonica-playing bluesman Billy Boy Arnold.

What was first known as Co-Ben opened for business in March 1953. It lasted through September, maybe October, of that year. To our knowledge, all recording for Co-Ben took place in March 1953, at one session. ool did not appear as the name of the label until the two singles were issued in July 1953. (Cool was described, on the labels and in both surviving advertisements, as a division of Co-Ben Recording.) We missed a couple of early indications of the company's activity because prior to the actual releases it was just Co-Ben. Our thanks go to Marv Goldberg for locating a short article in Billboard ("Bennett, Cosey Set up Co-Ben Recording," March 28, 1953, datelined March 21, p. 44) and a blurb in the Chicago Defender ("Chicago Trio Forms Record Company Here," April 11, 1953, p. 18). The two Co-Ben announcements referred to two titles by Herbert Beard and one by Charlie Bennett, which, according to the presumption then prevaliling, had been recorded already. Confusingly, the March 28 piece says the studio band was led by John Davis (maybe that had been the intention, but see below). The April 11 piece refers to it as the Hepsters (not to be confused with a doowop group that later recorded in Chicago for Ronel, or with Ellas McDaniel's Hipsters). Bob Carter wasn't tagged as the bandleader until records were released—without any of the titles previously announced.

Co-Ben was a partnership between Collenane Cosey, whose name appears twice in the composer credits, and Charlie Bennett, who, according to Steve Cushing, was her brother-in-law and was also a Cool artist. The Defender blurb further mentions Gwendolyn Bennett, who was Collenane Cosey's sister and Charlie Bennett's wife. The company's address was given as 1231 South Homan Avenue.

Collenane G. Cosey was born Collenane Clark in Illinois (most likely in Chicago, but confirmation would be nice) on November 12, 1909. She was the daughter of Palus and Maggie Clark, and in the 1910 and 1920 censuses was listed as residing at 2130 Fulton Street. In 1930, a "Coleman Clark," occupation "Decorator," was listed as living with brothers and sisters at 2126 Maypole Avenue; Bob Eagle thinks, plausibly, that "Coleman" was a garbling of Collenane. In 1943, she was credited, with Louis Jordan and her husband, Antonio Cosey, for "Ration Blues," which Jordan recorded in October (it was released on Decca 8654). Either Collenane or her sister Gwendolyn supposedly also wrote "Bonus Pay," which was recorded by Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson.

Collenane Cosey ran what The Blues Dream calls a "dowel factory over on 14th and Halsted" (p. 87). This looks like a (rare) transcription error; in a 2023 interview with Billy Boy Arnold, the reference is to a "doll factory." She was the mother of Pete Cosey (1943-2012), a guitarist active as a session musician for Chess in the late 1960s, and a member of Miles Davis's band in 1974. Antonio Cosey had died in July 1951, at the age of 44.

To use his full name, Charlie Bennett was Charles Logan Bennett. The item in the Defender for April 11, 1953 refers to him as "Charlie L. Bennett." The Blues Dream of Billy Boy Arnold calls him Logan Bennett or Peachtree Logan. Bennett had recorded once before, in 1949, for MGM. A single session was done at United Broadcasting Studios in Chicago, in the summer of that year, with a band billed as the "Riverboat Four"; according to The Blues Dream of Billy Boy Arnold, p. 87, Blind John Davis was the pianist on the session, and Walter Melrose was the producer. Although he apparently did not end up recording for Co-Ben, Blind John Davis deserves a little more attention here. The pianist was born John Henry Davis, in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, on December 7, 1913. In the 1930s, he was performing in Chicago, where he became a regular participant in sessions for the Melrose combine, with John Lee Williamson among others.

Two singles ensued fromm the Peach Tree Logan session, one released around October 1949 and the second around November; composer credits to Davis and Melrose can be seen on the labels. Bennett was billed as "Peach Tree" Logan and his composer credits went to "Logan." MGM did not invite Bennett back to the studio; however, Blind Johnny Davis, as he was billed on his sides for the company, cut sessions of his own at United Broadcasting (late 1949 and 1950), with a followup at Universal Recording in early 1951. According to Arnold, Bennett and Davis had been drinking buddies.

Co-Ben / Cool employed the mastering and pressing services of RCA Victor, as can be discerned from the matrix numbers. We also know that Cool used the RCA Victor studio on Navy Pier, because Billy Boy Arnold remembers it vividly:

We made the record at the RCA Victor Studio on Lake Shore Drive. There was two buildings with "RCA Victor" on them. The engineer told me, he said, "Yeah, I recorded Sonny Boy, Big Bill, and Memphis Minnie—all of 'em." So we used the same studio that Sonny Boy and them did their stuff in, and the same engineer. (The Blues Dream of Billy Boy Arnold, p. 81)

Although the four released sides have consecutive matrix numbers, which suggest that they were recorded at the same session with the same studio band, there were two different headliners. Arnold recalled the session as being split with Herbert Beard, two sides each. But Arnold also heard Beard's sides after they were released. It's distinctly possible that Beard kept going with his two tracks that did not see release, that Charlie Bennett (Logan Bennett, "Little Brother") followed Beard, and maybe Arnold wasn't still on the premises by then. For clarity's sake we've divided the listings by headliner. We've grouped together the Herbert Beard sides that were released with those that were not. These are then followed by Charlie or Logan Bennett's unreleased sides (which rate their own entry).

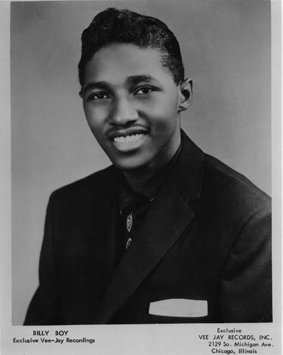

Bluesman Billy Boy Arnold was born William Arnold on September 16, 1935, in Chicago. He was raised on the South Side. Hearing records by John Lee "Sonny Boy" Williamson led Arnold to take up the harmonica. In late April 1948, he visited Sonny Boy Williamson at his apartment (3226 Giles) and sang and played along with one of Sonny Boy's records. On a second visit in May, he got some instruction from Sonny Boy. There would be no more visits because John Lee Williamson was murdered on June 1, 1948. Billy Arnold remained determined to play the harmonica, and determined to play the blues. He began hanging out with Blind John Davis, the pianist, and other blues musicians who knew Davis. Arnold's first public performances, in 1951, were on 47th Street with Ellas McDaniel’s street band; neither Arnold nor Jody Williams, who played guitar with McDaniel, was old enough to work a club. Arnold also started hanging out with Louis and Dave Myers of the Aces, which was then Junior Wells' group.

When Co-Ben picked him up, Arnold was 17, still living with his parents, and had his mind set on getting recorded. Probably toward the end of 1952, after Little Walter scored a major hit with "Juke," Arnold cut a demo of two of his songs (with the Red Devil Trio) and tried to get Chess and United to record him. Chance Records was ramping up its activity at the time, but does not figure in The Blues Dream of Billy Boy Arnold; apparently there was no thought of approaching Art Sheridan. Nor of approaching Joe Brown of JOB, even though JOB had scored its only hit record in 1952.

Blind John Davis learned about Logan Bennett's intention to start a record company and arranged to meet Bennett at Collenane Cosey's house. Arnold put together two songs to record (not the same two that had been on his demo) and he and Davis performed them for Bennett, who decided that Co-Ben would record Arnold (The Blues Dream of Billy Boy Arnold, pp. 87-88).

Arnold had decided on the musicians who would play the session:

The way that Blind John and I planned it, the session was going to be with the same guys that recorded with Sonny Boy. It was going to be Blind John on piano, Big Bill Broonzy on guitar, Judge Riley on bass, and Charles "Chick" Sanders on drums. That would have been a great deal for me. Blind John told Big Bill that we wanted him on the session, and he said, "I'll do it." Blind John told me that Big Bill said he was lookin' forward to it. Then he and Big Bill went to Paris to play over there for a while. (p. 88)

It doesn't appear, however, that Big Bill would have been available. According to Bob Riesman's book, I Feel So Good: The Life and Times of Big Bill Broonzy, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), Big Bill was out of town and out of the country for more than six months. He arrived in England on October 27, 1952 (p. 182), worked in England, Belgium, and Iceland before arriving in Paris in mid-December (p. 188), and was based in Paris for the remainder of his extended stay in Europe. He was performing in Paris from mid-January to mid-February 1953 (p. 193), and was back again in March and April (p. 195). Big Bill played a jazz festival in Frankfurt, West Germany, on May 4, 1953, and performed in Barcelona, Spain, before flying back to the United States on Air France, around May 15 (p. 197). His next project in Chicago would be recording for Chess Records.

Riesman does not mention Blind John Davis working with Big Bill in Europe in 1953; much of the time, Big Bill was appearing as a solo artist. But if Blind John did travel to Paris, he too may have been unavailable (with an uncertain estimated date of return) when Co-Ben wanted to do its recording.

According to The Blues Dream, Blind John was excluded on purpose. The pianist had suggested that Billy Arnold ask for an advance on royalties. When he made the request, Co-Ben was not amused, especially on discovering that Blind John had put Arnold up to it (p. 89).

Collenane Cosey and the Bennetts elected to go instead with the suaver backing of a studio ork led by Bob Carter.

We might wonder whether Co-Ben already had Carter and crew in mind for Herbert Beard and for Charlie Bennett himself. But if they did, why did the March 28 item announcing Co-Ben in Billboard attribute the accompaniment to "John Davis"? Normally, such announcements were not placed until after the recording session. The "Hepsters" (mentioned in the Defender) could have been a trial billing for Carter's ork.

"Hello Stranger" finds Arnold trying to sound like a cross between John Lee Williamson (in the harmonica intro, solo, and second verse) and Grant Jones, who recorded a number with the same title and a similar first verse for United in October 1952. Grant Jones' "Hello Stranger" was written by Sennabelle Richie Fenner, another Chicago-based female composer of blues. The Cool version is credited to Billy Boy Arnold, who apparently did write the second verse. Arnold recalls that he came up with "I Ain't Go No Money" so he would have original material to record, and that is consistent with the credit on the label.

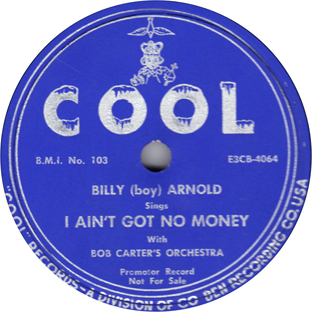

Although Billy Arnold was not mentioned in the Co-Ben announcements of March 28 and April 11, 1953, Cool 101/102 by Herbert Beard was advertised in Billboard on July 11, 1953 (p. 39) and Cool 103 seems to have followed it rather quickly. Backing was obviously by the same ork as on the Beard single, and the RCA Victor matrix numbers are adjacent. Hence our conclusion that the Arnold sides were recorded most likely in late March 1953, then released in July 1953. Arnold did not learn that he would be going as Billy Boy until Cool 103 was released and he saw the labels (Blues Dream, p. 90). Cool 103 also rated a mention in the company's Cash Box ad of September 19.

Billy Boy Arnold (hca, voc); unidentified (ts); unidentified (p); unidentified (eg); Robert James Carter (b); unidentified (d).

RCA Victor Studios, Chicago, March 1953

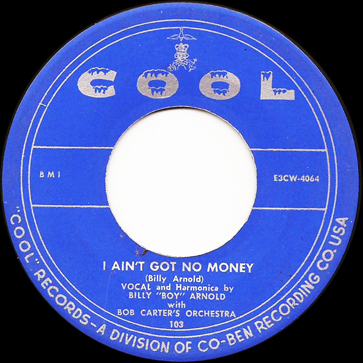

| E3CB-4064 E3CW-4064* |

I Ain't Got No Money (Arnold) | Cool 103, Wienerworld 5100 [CD] | |

| E3CB-4065 E3CW-4065* |

Hello Stranger ("Arnold") | Cool 103, Red Lightnin RL 0012 [LP], Wienerworld 5100 [CD] |

The Billy Boy Arnold sides appear to have been recorded first but released second. In the RCA Victor matrix series, E3 stands for 1953. The CB matrix number appears on the 78 and the CW on the (even more insanely rare) 45, which for some reason ended up with more detailed label copy. We've marked the copy from the 45 with an asterisk.

Red Lightnin RL 0012 was a British LP, issued in 1975 under the title Billy Boy Arnold: Blow the Back off It. There, "Hello Stranger" was transferred from a, well, less than pristine copy of Cool 103. The other tracks on the LP consisted of 2 unreleased Arnold sides from Chess and most of his output for Vee-Jay. See http://www.wirz.de/music/redlifrm.htm for a Red Lightnin discography.

In 2017, both Billy Boy Arnold sides were included in a 5-CD box set on Wienerworld 5100, Down Home Chicago Blues: Fine Boogie.

Arnold's next recording opportunity arrived while he was working with Ellas McDaniel, he took McDaniel to Chess Records, and Leonard Chess decided to record them. The session was what made Ellas McDaniel Bo Diddley. Arnold actually cut two of his own numbers at the end of the same session for Chess, on February 2 and 3, 1955, but Leonard Chess did not seem interested in releasing them. So Arnold went across the street to Vee-Jay, which had not been interested in recording McDaniel; Vee-Jay signed Arnold. At his first session for his new label on May 5, 1955, he recorded his breakthrough number, "I Wish You Would." Arnold had previously shopped the number to Chess, which hadn't recorded it; he wrote new lyrics for the Vee-Jay session. Bo Diddley then recorded a variant as "Diddley Daddy"; Arnold was present at that Chess session but preferred not to play on "Diddley Daddy."

Herbert Beard (voc); unidentified (ts); unidentified (p); unidentified (eg); Robert James Carter (b); unidentified (d).

RCA Victor Studios, Chicago, March 1953

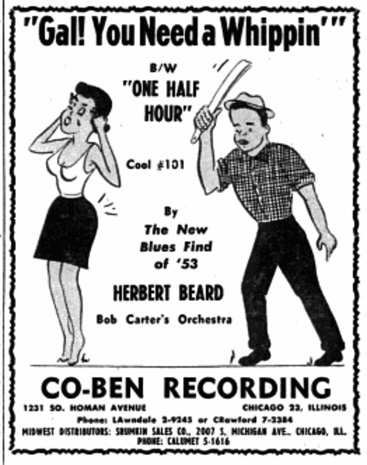

| E3CB-4066 | Gal! You Need a Whippin' (Cosey) | Cool 101, Electro-Fi CD 3378 | |

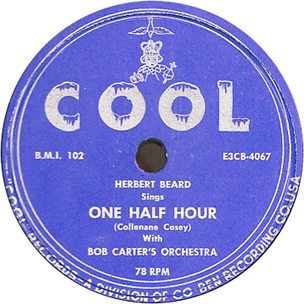

| E3CB-4067 | One Half Hour (Cosey) | Cool 102 | |

| Luxury Tax Blues (Cosey?) | Cool (unreleased) | ||

| Rhythm in My Soul | Cool (unreleased) |

Who Herbert Beard was, we have no idea. His four sides for Co-Ben constitute his entire recorded legacy. The initial announcements for Co-Ben (Billboard, March 28, 1953; Chicago Defender, April 11, 1953, p. 18) mentioned only the titles that were left unreleased, and variously identified the band as the John Davis ork (March 28) or the Hepsters (April 11). What was actually released in July 1953, as Cool 101/102, used the two titles not prevously announced. Either Co-Ben wasn't quite accustomed to the release number concept, or at some point between March and July 1953, different pairings of the four Beard sides were planned but not used. Billboard ran a display ad for Cool 101/102 (July 11, 1953, p. 39) and a quick announcement for it ("Co-Ben Releases First Two Sides", p. 16) in the same issue. The brief article referred to it as a Co-Ben release, not a Cool. In September, the Cash Box ad for Cool mentioned a second "Herb" Beard single. There is no evidence that the second single ever appeared. With just one session for Co-Ben, all four Herbert Beard sides go here: recording in March 1953, release of Cool 101/102 in July.

Cool used RCA Victor's custom pressing service, which argues for releases on 45 rpm. (Victor had introduced 45s in 1949 and, as a combatant in the format wars then raging, had started its custom pressing service to encourage independent record companies to put their singles on 45s.) We know only of 78 rpm releases on Cool 101/102. Cool 103 was released on 78 and 45, so a 45 of 101/102 might still be out there.

"Gal! You Need a Whippin'" was reissued in 2003 on an Electro-Fi CD, a various-artists compilation from Canada titled Midnite Blues Party Volume Two: Rare Blues and Rhythm & Blues from the 1940's & 1950's.

Cool 101, as it was billed there, was the focus of the company's only ad in Billboard, which appeared on July 11, 1953 (p. 39). Its theme of cartoon domestic violence is unlikely to have appealed to most readers, and the single got no further attention from the trade magazine (neither would Cool 103). Since the opening of Co-Ben had been announced in Billboard for March 28, 1953 ("Bennett, Cosey Set up Co-Ben Recording"), it seems that the partners took some time to decide on a name for their label, and some more time to get records pressed for release in July.

Courtesy of Dan Kochakian we learned of a second ad for Cool, which appeared in Cash Box on September 19, 1953 (p. 18). Mercifully free of illustrations, it appends to Cool 101/102 (now called Cool 102) and Cool 103 "2 Sensational New Releases," for which artists and titles are provided but not numbers. Herbert Beard was due for a second single, to consist of "Luxury Tax Blues" and "Rhythm in My Soul." (The titles had first been mentioned in the Billboard article announcing Co-Ben's formation, back on March 28.) McGrath's R&B Indies (2nd edition, Vol. 1) puts the two titles that we know as Cool 101/102 on Cool 101, then ascribes two further Herbert Beard titles (without matrix numbers) to Cool 102. McGrath says they were "Luxury Tax Blues" and "Oh Rhythm." "Luxury Tax" is a number that Collenane Cosey (or was it Gwendolyn Bennett?) claimed to have written for Eddie "Cleanhead" Vinson, but it is credited on the original release to Vinson and Jessie Mae Robinson. McGrath also turns "One Half Hour" into "One Half Pint"; wherever his information arose, it didn't come straight from the Cash Box ad.

The Cash Box ad also promised a single by "Charley" Bennett, "Half Past Three" b/w "Zig Zag in Love." This wasn't mentioned by McGrath. According to the Billboard article of March 28, Charlie Bennett sang on "'Half-Past Three in the Morning,' a novelty." The same tune was mentioned in the Defender article of April 11. According to the Defender piece, the (Logan) Bennett record was then meant to appear as the work of "Little Brother."

Charles Logan Bennett (voc); unidentified (ts); unidentified (p); unidenified (eg); Robert James Carter (b); unidentified (d).

RCA Victor Studios, Chicago, March 1953

| Half Past Three | Cool (unreleased) | ||

| Zig Zag in Love | Cool (unreleased) |

Anything we know about "Zig Zag in Love" derives from that one ad in Cash Box (September 19, 1953, p. 19). The ad marked the end of Cool and Co-Ben's effort to stay in business. Charlie Bennett's sides were presumably done at the same session as the two by Billy Boy and the four by Herbert Beard; hence we have also put the Bob Carter combo behind him. Where the band was referred to in various ways in the earlier Herbert Beard annoucements, neither of the earlier announcements of "Half Past Three" (March 28 and April 11) identified the band at all.

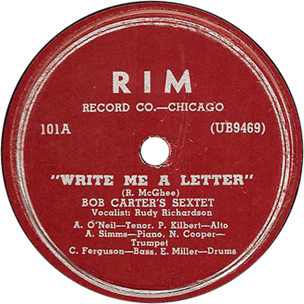

One of several questions that have lingered about Co-Ben and Cool is who Bob Carter was. We are reasonably sure that this Bob Carter previously led a sextet in 1949, for another minuscule operation called Rim, whose street address (500 East 63rd Street) seems to put the company in a back room, either at Miracle Records or at Miracle's cooperative distributor (at the time the distributor was housed at the same location.) Rim produced three vocal sides for singer Rudy Richardson and one instrumental, which appeared on Rim 100 and 101. Now we used to think the Bob Carter of Cool and Rim wasn't the Bob Carter who previously recorded for Specialty, Sunbeam, and Universal. That Bob Carter (full name Robert James Carter, born in Alabama in 1917) played string bass; the Bob Carter who recorded for Rim was a non-playing leader who turned the bass playing over to Curtis Ferguson.

However, Robert James Carter who played the bass was working in Chicago as a leader in 1953, and the only musician who has been identified in discographies as playing on the Co-Ben/Cool session is Curt Ferguson. Was this on the authority of Rim labels from 1949? What makes a lot more sense is that Robert James Carter put the band together for this session and played the bass himself. In The Blues Dream, Billy Boy Arnold, who was unhappy with Charlie Bennett's decision to use these musicians on the session, says:

They went and got another band, different session musicians in Chicago, while Big Bill and Blind John was in Paris, and that's who I ended up recording with. They wasn't no group, but the record label called 'em "Bob Carter's Orchestra." Bob Carter was the bass player on the session. (p. 89)

Arnold, who wouldn't have recognized any of the musicians from the down-home blues scene in Chicago, also wouldn't have known who was working with Bob Carter at the Rose Bowl Casino. If Carter was leading a quintet, he could have brought his whole combo to RCA Victor Studios. If Carter had a trio, he could have recruited a saxophonist and a drummer (etc.) for the session. Unfortunately, we know neither the size of Bob Carter's group in 1953, nor the lineup.

As the solitary Billboard ad indicated, with just one Chicago-based distributor, the company wasn't going to move its product to any distant locales. It didn't help that the ad misspelled the distributor's name: it was Frumkin Sales, run by Hy Frumkin, who generally handled a bunch of small labels. At least the address and (we assume) the phone number were correct. Frumkin carried so many labels that he couldn't fit most of them into his display ad in Cash Box (July 18, 1953, p. 43); Cool was too new and too small to make the cut. After the two releases on Cool, in July 1953, and the fizzled announcement in September, heralding records promised since March that never arrived, nothing more was heard of Co-Ben or of Cool. The company exhausted its capital recording and mastering 8 sides and pressing and releasing 4 of them.

Billy Boy Arnold recalls pitching Cool 103 to Leonard Chess, something he was surely asked to do as Co-Ben shut down. Arnold, who describes Cool as being distributed by RCA Victor (if it had been, the record wouldn't be so rare today), says that he was asking Chess to distribute Cool 103. He had to be making a bid for a lease on the master, if not an outright sale. "That was the first time I met Leonard. He played it and said, 'This has already got too much airplay. I can't use that.'(Blues Dream, p. 91)." Arnold recalls that his Cool record hadn't been selling in Chicago (surely the only place where anyone could buy it), but it was getting played on the radio in Chicago. Apparently Cosey and the Bennetts had been able to slip some money to Al Benson.

Collenane Cosey retained her connection with Louis Jordan, who recorded his own version of "Gal, You Need a Whippin'" in January 1954, during a whirlwind series of sessions that took place immediately after he left Decca for Aladdin. It was released in February 1955 on Aladdin 3279 (see the review in Cash Box, February 26, 1955, p. 32, and an advertisement for the record in Cash Box for April 2, 1955, p. 69). By then, Cool had been completely forgotten. We also don't know of any further recordings by Charlie or Logan Bennett. If Billy Boy Arnold's account is correct, the decision to bring in Bob Carter's ork meant that Bennett was no longer on speaking terms with Blind John Davis. Meanwhile, the brief transit of Co-Ben and Cool Records could not have had any lasting effect on Davis. He remained active as a musician in Chicago for another three decades. Blind John Davis died of a myocardial infarction in Chicago, on October 12, 1985.

The fate of the Co-Ben masters is unknown. Two Herbert Beards and the two Charlie Bennetts, repeatedly announced but never released, have flown we know not where. All reissues have had to be taken off the two Cool releases. Not that the label's output has drawn much reissue attention. One Billy Boy Arnold side was reissued on a Red Lightnin LP in 1975. Both finally made it, in much better sound, onto a 5-CD boxed set of Chicago blues in 2017 and a single CD from 2018 titled Windy City Dandies. One Herbert Beard side came out in 2003 in a various-artists compilation CD on the Electro-Fi label, and on the Windy City Dandies collection.

After Co-Ben and Cool closed, Collenane Cosey moved to Phoenix, Arizona. In 1956, she was operating Top Hat Cleaners at 533 East Jefferson; her son Pete spent his teenage years in Phoenix. She returned to Chicago at an unknown date, living at 909 West Foster Avenue. In the early 1970s, she ran a child care center that she made available after hours to the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, which used the space for music classes and rehearsals. Collenane Cosey died on September 3, 2010, at the age of 100.

Cool is a kind of obvious name for a record label. According to McGrath, the Chicago-based operation was the first R&B-oriented company to use it, but others would follow: a fairly prolific Cool label out of Harrison, New Jersey, was active from 1958 to 1961; a doo-wop Cool label of uncertain location was active in 1960; another blues label from Chicago in the 1960s. To these Bob Eagle has added the Miami-based label of one Dr. Cool, in the 1970s.

Our thanks to the late George Paulus, to Bill Sabis, and to Dr. Robert Stallworth for photos of some extremely rare records, to Bob Eagle for his biographical research, to Marv Goldberg for catching references to Co-Ben before it was Cool, and to Dave Penny for help with the very sparse reissues as well as the composer credits on two tunes Collenane Cosey told Steve Cushing she had written for Cleanhead Vinson.

Click here to return to the Red Saunders Research Foundation page.

Click here to return to Robert L. Campbell's Home page.