Revision note. Courtesy of Alex Podlecki, we now know of two Country and Western releases on Sultan, both in a 5000 series and both by Lawton "Slim" Williams (see https://www.45worlds.com/78rpm/label/sultan). Craig Maki, the author of Detroit Country Music (University of Michigan Press, 2013) has provided us with the matrix numbers for Williams' Sultan 5001 (email communication, February 11, 2025). Maki (email of March 10, 2025) further notes the possibility that the Williams sides were cut in Chicago, rather than Detroit. We have a real biography of Morton Sultan, and have discovered a fourth jazz session for his label, which took place in Chicago around July 1, 1946. Chet Roble was a pianist who had a locally renowned trio, with Boyce Brown on alto sax and Sammy Aron on string bass. Unfortunately, the session was attested in a quick Detroit item in Billboard that misspelled the leader's name and the name of the club where the trio was playing. Of course we haven't seen a release, though it won't hurt to look. And we have learned of two more records by Cantor Hyman Adler: 1001, which was released by Sultan, and 1003, which carried a modified label after Morton Sultan sold the Cantor Adler masters to another company. We are indebted to Eddie Wiggins' son Chuck Wiggin, who informed us (phone conversation of February 13, 2014) about his father's 45 rpm singles on the Disc-Co and Beam labels.

Sultan Records was one of the myriad of little labels that mushroomed nationwide following World War II. The label was run by Morton Sultan in Detroit, and came out with five known releases in 1946 and one in 1947. Initially the firm was located in the Penobscot Building (645 Griswold Street) in the downtown section. While RSRF is devoted to coverage of Chicago labels, we are making an exception for Sultan, because its jazz artists were all located in Chicago and the company recorded them in Chicago. During this period, Detroit was not a major recording center, and Morton Sultan's later purchase of a studio did not make it into one. A June 1946 Metronome article by Barry Ulanov mentioned a handful of small companies in Detroit: Vogue, Willow Walk, Sultan—which he describes as strictly a jazz label—and Harmeny. Ulanov complained that with the exception of Harmeny, they featured little local talent. Companies that would have a somewhat bigger footprint, like Sensation and Fortune, had not set up shop yet.

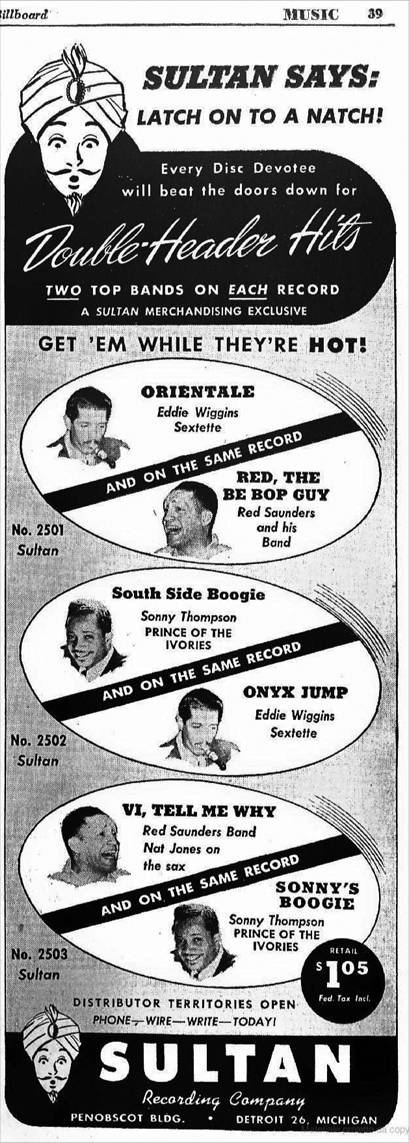

In its initial releases, Sultan employed a gimmick, featuring different artists on each side of each 78. The first release featured the combos of alto saxophonist Eddie Wiggins and drummer Red Saunders; the second Wiggins and pianist Sonny Thompson; and the third, Saunders and Thompson. Sultan promoted this marketing ploy as "double-header hits," in a full-column advert for the June 8, 1946 issue of Billboard (p. 39). It is the only display ad for Sultan that we have ever seen.

These artists were all regulars on Randolph Street in Chicago's downtown (commonly called the Loop for the elevated structure that circles the commercial section). Randolph Street, with its string of jazz clubs, was the local counterpart of New York City's 52nd Street. From 1945 to 1947, Wiggins was working regularly at the Brass Rail (52 West Randolph). Next door in the Garrick Theater Lounge (58 West Randolph), Sonny Thompson had played the Garrick Bar (the street level room). Meanwhile in the Downbeat Room (the downstairs venue) Red Saunders had a continuous engagement from August 1945 to September 1946, when the Garrick Lounge closed.

Morton Sultan was born in Detroit on August 31, 1921, which made him a few years younger than the artists he recorded. His parents, Louis and Fannie Sultan, were originally from Rochester, New York. From 1932 till his retirement in 1950, Louis Sultan owned a Chevrolet dealership at 5100 Grand River in Detroit. Morton was the youngest of four children. Although his parents were not musical, his sister Lottie played the piano; his brother Henry played the saxophone; and his brother Aaron played the cornet.

Lottie, who was born on July 27, 1908 while the family still lived in Rochester, studied at the Detroit Conservatory of Music, and was playing the piano in public in 1918, before her kid brother Morton was born. According to her obituary, she graduated from the Paris Conservatory. We have not found a notice of an appearance in Detroit after 1923, when Lottie was 15. She married McArthur Colton, a dentist, and apparently did not perform in public afterwards.

According to a syndicated story that ran in 1926, "When Morton was barely two, he would sit at his sister's side while she practiced, quietly listening to the music. When she had finished he begged her to show him how to play, and actually cried when she at first refused" ("'I Am Little Mozart,' Says Boy Prodigy, and His Skill Shows He's Not Boasting," The Daily Journal [Vineland, New Jersey], June 11, 1926, p. 3). Soon he was taking lessons five days a week from Mrs. Rose Rubinstein (a professional, who was also Fannie Sultan's sister). His parents took him to a recital by Paderewski, and "the boy was enraptured." The occasion for the syndicated piece was a children's piano contest in Detroit; Morton had qualified for the finals, which were to be held in August. "Morton has no regard for jazz music. Among the masters he prefers Mozart and Beethoven." He would have time to change his mind.

The Greater Detroit Piano Playing Contest was sponsored by the Michigan Music Merchants' Association. The winners were Judith Sidorski, who was 14, and William Reilich, 10. "The infant prodigy, Morton Sultan, 4 years old, also was heard and was presented with a silver loving cup and ring as the youngest contestant" ("Scope of Piano Test Widened," The Detroit Free Press, August 19, 1926, Part Two, p. 1).

Morton Sultan was indeed a prodigy. He was not a Mozart or a Saint-Saëns or a Nyiregyházi, not even a Glenn Gould. Once in a while he was "hypoed" in the newspapers, but his family didn't need income from his performances and he was not exploited.

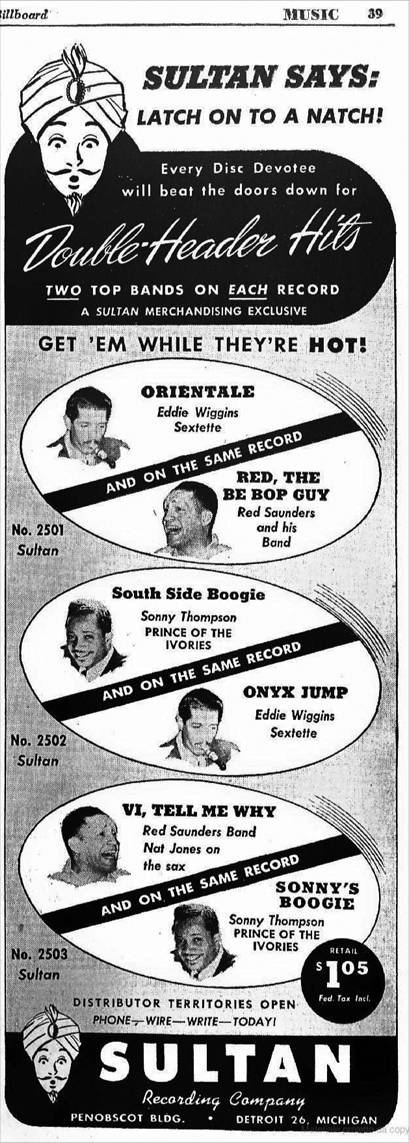

Morton moved up to studying with Guy Maier (1891-1956), who taught at the University of Michigan from 1921 through 1931 and at Juilliard from 1935 to 1942. He gave occasional concerts. On February 10, 1933, Morton Sultan appeared in a concert at the Detroit Insitute of Arts, organized by violinist Jeanne Reol Beaume (Detroit Free Press, February 5, 1933, p. 32, pt. 3, p. 12). On November 8, 1933 he performed sonatas for violin and piano with her (Detroit Free Press, November 8, 1933, p. 17).

At the summer music camp in Interlochen, where Maier was the top piano instructor, Morton Sultan performed on a number of occasions in 1934 (Elsie Katterjohn, "Spotlights on Music Bowl," Traverse City Record-Eagle, June 30, 1934, p. 8. On February 27, 1938, he appeared with the Detroit Civic Orchestra, Karl Wecker conducting, playing Liszt's G major concerto (Detroit Free Press, February 27, 1938, pt. 3, p. 16). (The pre-concert publicity declared that he had studied in Paris with Alfred Cortot and Wanda Landowska. If so, Lottie must have introduced him to them.) On March 10, 1938, he appeared as a soloist in a concert at the Women's City Club in Detroit featuring performances by students in the public school system. It was sponsored by the Musical Coterie of the Twentieth Century Club (Detroit Free Press, March 6, 1938, pt. 3 p. 8). He performed Beethoven's first piano concerto with Izler Solomon and the Illinois Symphony Orchestra, on a program with works by Paul Hindemith and Jacques Ibert (Edward Barry, "Vital Concerto of Hindemith Stirs Audience," Chicago Tribune, May 16, 1938, p. 13).

The last notice came when Morton was 17. He performed at a special gathering of 500 people in the sales and service garage of his father's company, Grand River Chevrolet ("Garage Becomes Theater for Night," Detroit Free Press, December 15, 1938, p. 19). By that time, he was traveling regularly to Chicago for lessons with Rudolph Ganz (1877-1972) at Chicago Musical College.

Morton Sultan appears to have decided that life as a performer was not for him. He would not join such Maier students as Leonard Pennario, or such Ganz students as Dorothy Donegan. He served in the Army during World War II. In November 1944, Sergeant Morton Sultan was in the 1620th Headquarters and Service Company, stationed at Camp McCoy near Tomah, Wisconsin ("10-Pin Club Has Seven Members," Wisconsin State Journal, November 14, 1944, p. 13).

Morton Sultan must have made it a practice, on trips to Chicago, to frequent the Randolph Street clubs. He launched his label with the artists he saw at these clubs in mind.

The company's first three recording sessions took place some time in May 1946. (The Red Saunders sides include altoist Nat Jones, who replaced Antonio Cosey in the Saunders combo in early May, according to a story that ran in Down Beat's "Chicago Band Briefs.") The company's founding was announced in Billboard on June 1, 1946 (p. 133). Although Morton Sultan was always identified as the president of the firm, he had three partners: Sidney Verier, Samuel A. Grossbart, and his father, Louis Sultan.

Around the same time, Morton Sultan set up as a distributor. The formal announcement was delayed: "Sultan Distribution Company will be established at 12727 Linwood Avenue by partners, Morton Sultan, Sidney Verier, S. A. Grossbart, and Henry Sultan, to distrib Sultan Records and other lines" (Billboard, July 20, 1946, p. 123). In fact, Sultan Distibutors at the Linwood address was on the list in an ad for trombonist Jack Teagarden's new record label (Billboard, June 22, 1946, p. 35). Picking up Teagarden Presents showed good taste, though not good commercial instincts. A better pickup, commercially speaking, was the Manor label out of the New York area; Sultan was listed as a Manor distributor in an advertisement from November 9, 1946 (Billboard, p. 31).

All three Sultan singles in the 2500 series (2501, 2502, and 2503) were released in June 1946. Sultans in the 2500s carry matrix numbers in an S-100 series. We don't know where they were recorded, but considering the date and the nature of the music, the Myron Bachmann studio is a good guess. A number of gaps imply that more sides were actually recorded than the 6 that saw issue (4 tracks per 3-hour session was the norm in those days). However, we have no idea what happened to any unissued material—if anyone preserved it.

Sonny Thompson (p).

Chicago, May 1946

| S-106-1-1 | South Side Boogie (Thompson) | Sultan 2502A | |

| S-108-1-1 or S 108-1-2 | Sonny's Boogie (Thompson) | Sultan 2503B |

The pianist was born Alphonso Thompson in Memphis on August 22, 1916. While he was a preschooler, his family moved to Chicago. Both of his parents played piano, and he began his studies on the instrument while in elementary school. He attended Wendell Phillips High School, where he played drums and French horn in the marching band and piano in the orchestra. He studied at the Chicago Conservatory of Music for 3 years (during this period he performed in concert on many occasions, one of which was a tour of cities in Canada). In the clubs he learned his craft from Art Tatum and Earl Hines.

Thompson began working in combos while in high school and went on the road for extended periods after graduating from Phillips. He also spent some time in the band of Erskine Tate. He began working as a leader in 1940, with a group billed as Sonny Thompson and His Swingsters. That year, he performed 7 days a week at the Apex Grill and Road House, in the small African-American suburb of Robbins.

During 1941 and 1942, Thompson attended the University of Chicago, supporting himself by playing gigs. During 1941 and the first quarter of 1942, he played solo piano at the Garrick Stage Bar. When they were temporarily in need of a pianist, he also worked in groups led by Lonnie Simmons, Red Allen, and Stuff Smith in the Down Beat Room downstairs. On March 19, 1942, his contract with New Club Plantation (3520 South State) was accepted and filed by Musicians Union Local 208. The club, which featured an elaborate floor show, ran an ad in the Chicago Defender for April 11, 1942 promising "Music By Prince Alphonso and His Rhythm Masters." However, New Club Plantation shut down on May 10 (see Local 208 Board minutes for May 21).

Thompson resurfaced at the Apex in Robbins, in a band led by Recard Grey, who had taken over as leader at some point in 1941. However, his association with the club ended in mid-June 1942 after Fats Robinson, the owner, complained that Thompson "had too much influence over Grey," that he took too many outside gigs and sent too many substitutes. The latest irritant: Thompson had refused to play a request for a customer —in fact, had left the bandstand—because the singer ("entertainer" is the word Local 208 used) wouldn't share her tips with the band (Local 208 Board minutes, June 18, 1942, p. 3).

In 1943 Sonny Thompson entered the Army (we don't know whether he volunteered or was drafted) and was assigned to the Signal Corps. While doing construction work, he was seriously injured in a cave-in accident. After a spell in the hospital, he was sent home on a medical discharge and had to spend the rest of the year recuperating.

Thompson resumed musical activity when he posted a contract on January 6, 1944 with the Garrick Stage Bar, where he played solo piano. Next he moved to Howard Street on the city's northern border to work the Bar o' Music, a joint that featured solo pianists and trios; contract accepted and filed on March 2. In February 1945, Thompson got a break when he was asked to step in to replace Earl Hines at El Grotto, a prestigious club located in the basement of the Pershing Hotel, 64th and Cottage Grove (his contract for 1 year at El Grotto was accepted and filed on February 15, though this was later scaled back to a mere "indefinite"). Apparently the arrangement to replace Hines was made well in advance of a planned tour; Down Beat's "Chicago Band Briefs" for May 1, 1945 (p. 4) has Hines about to go on the road after playing to packed houses at El Grotto for 9 weeks, and Thompson's 16 men "comprised of several top sidemen from various name bands" about to open on May 3.

An item in Down Beat (July 15, 1945, p. 4), "Thompson Has Fine New Crew," described the band as a "14-piece outfit" and noted that the show's current headliners were singer Ivie Anderson and singer-dancer Marie Bryant (both of whom had worked with Duke Ellington). For 6 months the band was featured on nightly radio broadcasts. Thompson appears to kept his El Grotto band together through the end of 1945, but times for big ensembles were getting tough, and shortly after New Year's, 1946, he took a solo job at the Vanity Show Lounge on the West Side (his contract for 5 weeks there was accepted and filed on January 17). Still working solo, on May 2 he posted a 1-week contract with the Normandy Lounge on the far North Side; on May 16, he filed a contract for 2 weeks at Tony's Lounge (which is probably where he was working when he cut his session for Sultan). In June or July, he got the opportunity to work a high-profile gig in New York City.

Thompson made his first recording session with a sextet backing June Richmond on Mercury Records; two singles were released. The two sides he did for Sultan were his first as a leader. Thompson, billed for the occasion as the "Prince of the Ivories," split one 78 with the Eddie Wiggins combo and another with Red Saunders.

Metronome in the September 1946 issue reviewed the two Sonny Thompson sides thusly, "This is the pianist who came into the Café Society Uptown two months ago. It's said he's potentially great, but since both these sides are just so much fast flashy boogie woogie, with a meaningless pseudo-classical departure, we'll reserve our raves." By this time, most jazz reviewers had grown jaded about boogie woogie, which numerous bandleaders had adopted and marketed in slick renditions, and quite a few soloists had also adopted and marketed in slick renditions.

In the Sharon A. Pease profile of Thompson that ran in Down Beat, his involvement with Sultan was described as follows:

Recently he did the first of a series of solo sides for Sultan. Sonny also sings and some future Sultan releases will feature his voice as well as his piano.

We of course don't know whether Pease was referring to vocal numbers that Thompson had already recorded, or to a future session that never got past the projected stage.

During 1947 Thompson teamed up with the Dick Davis Combo to play regularly at the Tradesmen's Lounge (6240 Cottage Grove), appearing with them on a recording session for the fledgling Miracle label in January. Thompson began recording under his own name with Miracle in mid-1947, using the Sharps and Flats as his rhythm section and frequently adding Eddie Chamblee's tenor sax. He reached the peak of his performing career, striking gold with one of the biggest R&B hits of the late 1940s, "Long Gone" (released in the spring of 1948). Other hits on Miracle followed. After Miracle folded, Thompson moved to King Records in 1950, and recorded extensively for that company (occasionally doing session work for Vee-Jay and other labels). He handled A&R for the label until 1964, when King closed its Chicago office, but continued as a freelance producer for a few more years. Thompson died on August 11, 1989.

Sources used for our Thompson profile were Sharon A. Pease, "Chi's Thompson Turns to Solo Work and NYC," Down Beat, 15 July 1946, p. 12; "Record Reviews," Metronome, September 1946, p. 40; Tony Burke and Dave Penny, "Screaming Boogie," Blues & Rhythm: the Gospel Truth 37 (June-July 1988): 9-14; Robert Pruter interview with Catherine Hayes Thompson, 6 September 1989.

Red Saunders (d, voc, ldr); George "Sonny" Cohn (tp); Joseph "Buster" Bennett (voc, as -1); Nat Jones (as); Leon Washington (ts); Porter Derrico (p); Mickey Sims (b).

Chicago, May 1946

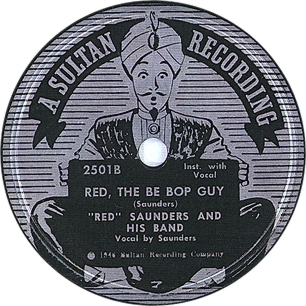

| S-109-1 | Red, the Be Bop Guy ("Saunders") -1 | Sultan 2501B | |

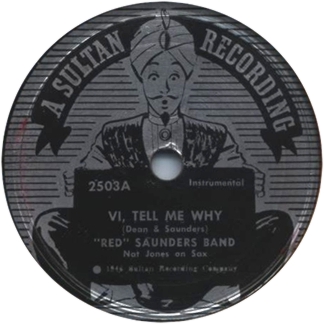

| S-111-1-1 or S 111-1-2 | Vi, Tell Me Why (Dean-Saunders) | Sultan 2503A |

Drummer Theodore "Red" Saunders was born in Memphis on March 2, 1912, moving to Chicago in 1923. He became a professional musician in 1928. After nearly a decade of work under various leaders, by early 1937 he had joined the Club DeLisa house band. He assumed leadership in July of that year, gradually building the band from a six-piece combo to a 13-piece unit. In June of 1945, Saunders and his band left the Club DeLisa to go on an overseas tour entertaining troops. The tour fell through, and Saunders downsized his band to a sextet. He got a job in Chicago's Loop at the Capitol Lounge (167 North State), one of several Loop venues owned by Milt Schwartz and Al Greenfield. During this absence from the Club DeLisa, Saunders made his first and second recordings under his own name, for Savoy in December 1945 and then for the Sultan label. (For a full biography and discography see our Red Saunders page.)

Saunders moved to the Garrick Lounge's Downbeat Room (58 West Randolph) in August 1945. The Garrick Lounge was owned by a colorful ex-boxer Joe Sherman, who would stand outside the club shouting "showtime, showtime," and practically drag customers off the street. On April 8, Down Beat ran a photo of the band with a long caption: "Red Saunders Garrick's Star. Red Saunders is the current dynamic attraction at Randolph Street's Garrick Bar [meaning the Downbeat Room]. Red, acclaimed one of the top drummers by all who hear him, has had his fine six-piece combo at the Garrick's Downbeat Room since last August. With Red are Mickey Simms bass; Porter Derrico, piano, Sonny Cohn, trumpet, Tony Casey [sic], alto, and Leon Washington, tenor. Group has been pulling more business than Red Allen-J.C. Higginbotham group..." On May 6, "Chicago Band Briefs" reported that altoist Nat Jones (who had been in the Club DeLisa band before Red departed the club) was rejoining Saunders at the Downbeat Room. This was the band that recorded for Sultan Records.

"Red, the Be Bop Guy" was the B-side of Sultan 2501; the A-side was "Orientale" by the Eddie Wiggins Sextette. "Vi, Tell Me Why" shared its "double-header" disc with "Sonny's Boogie" by Sonny Thompson. (According to Daniel Gugolz, some copies of Sultan 2503 do not designate A and B sides. His copy has S-111-1-2 for "Vi, Tell Me Why.")

A listen to Sultan 2501 reveals that label indulged in some false advertising when it attributed the vocal to Red. The vocalist is none other than Buster Bennett and the tune is a fairly fast blues of the "celebrity roast" variety.

He's hip and he's handsome, he's mellow and fly

Yes, he's hip and handsome, he's mellow and fly

The gals all call him Red the bebop guy

He has so much trouble to keep the chicks from his flat

Yes, so much trouble to keep the chicks from his flat

He has to beat 'em off with a baseball bat...

You may think he's boasting, he's just a big sack of wind

Yes, he's boasting, he's a big sack of wind.

Then he's the biggest sack since time began.

The words are obviously Buster's, and could well have been improvised at the session—but Red took the composer credit. Some of the riffing between Buster's vocal lines would be reused when Red's combo backed Big Joe Turner a few months later.

Sonny Cohn has a prominent trumpet lead in the introduction and the tag. In the middle of the piece, there are two 12-bar solos on the alto saxophone. The first solo, stuffed with 8th and 16th notes in the mid-1940s Tab Smith manner, is obviously the work of Nat Jones. The second 12 bars are strictly gutbucket and enunciated with a rasp—Buster's doing. And the second solo ends with a rest (so Buster could get the horn out of his mouth and resume singing). Buster also briefly joins the closing ensemble. Our thanks to Armin Büttner for catching Buster's presence on this side. The subterfuge was deemed necessary because Buster was under contract to Columbia at the time.

The Billboard ad for "Vi, Tell Me Why" mentions "Nat Jones on the sax" (the label for Sultan 2503 words it as "Nat Jones on Sax"). Vi Kemp, a contortionist and singer, was Red Saunders' wife. She is mentioned in many subsequent Chicago Defender advertisements for the Club DeLisa (May 17, 1947; December 18, 1948; and December 31, 1949, among others). "Vi, Tell Me Why" was a ballad dedicated to Vi, but not featuring her. As promised, Nat Jones gets the rather sappy alto sax lead and the frilly conclusion; there is also a brief trumpet lead from Sonny Cohn.

Metronome gave a mixed assessment to the sides in its September 1946 review. Referring to "Red, the Be Bop Guy, the journal said, "Saunders' little Chicago band does a vocal novelty that sounds more like typical jump music than be bop. It's a medium-tempo blues with a good beat and some tricky alto by Nat Jones [it sounded trickier because Jones traded off with Buster Bennett]. The same Mr. Jones, who played clarinet for the Duke for a while some three years ago, plays a sweet solo on 'Vi,' but the band and performance are out of kilter and perhaps a trifle off center." The Metronome review correctly noted the complete absence of bebop on "Red, the Be Bop Guy." None of Red's musicians were beboppers. Yet the band would master the style by the end of the decade, when they cut Charlie Ventura's "Synthesis" for the Supreme label.

Saunders performed at the Downbeat Room until Joe Sherman closed down his operation in September 1946. Saunders then took his band to New York's famed Kelly Stables (during their stay in NYC they recorded behind Big Joe Turner for National). On the way home, the Saunders band worked Detroit's Club Zombie for 3 weeks in December 1946; could Morton Sultan have had anything to do with this booking? The Red Saunders combo was back in Chicago in January 1947, playing in the Loop at the Band Box. On May 19, 1947, Red made a triumphal return to the Club DeLisa, where he would remain until the black and tan closed its doors in February 1958.

Red Saunders sources: "Red Saunders Garrick's Star," Down Beat, 8 April 1946; Don [Haynes], "Bands Dug at the Beat," Down Beat, 1 August 1945, p. 4; "Record Reviews," Metronome, September 1946, p. 39; "Downbeat Room Closes in Chi," Down Beat, 23 September 1946, p. 8. We are indebted to Lars Bjorn for material from the Michigan Chronicle pertaining to Red's gig at Club Zombie.

Eddie Wiggins (as-2; ob -1); Gene Russell (p); Red Cody (vib); Frank Gassi (eg); Jack Fonda (b); Steve Varela (d).

Chicago, May 1946

| S-114-1 | Orientale (Wiggins) -1, 2 | Sultan 2501A | |

| SS 115-1-1 | Onyx Jump (Wiggins) -2 | Sultan 2502B |

Alto saxophonist Eddie Wiggins was born in Edwin Charles Wiggin in Tacoma, Washington, on January 22, 1917; he always used "Wiggins" as his stage name. Eddie Wiggins first toured on the West Coast in a group called the Four Esquires, and eventually found himself in the big time, playing in the Stuff Smith Orchestra and Billie Holiday's band. He also worked in the Boyd Raeburn band, probably in 1943 while Raeburn held down a 9-month residency at the Band Box. Returning to Chicago in 1944, Wiggins missed Raeburn's "progressive jazz" period, but was able to establish himself in Chicago's Loop (downtown) on Randolph Street, the local equivalent of New York's 52nd Street.

The five-piece group that the alto saxophonist led was one of the hottest bands on Randolph Street during the mid-1940s. The group played for years at the Brass Rail (52 West Randolph), in the same building as the large basement club, the Band Box (54-56 West Randolph). Both were among the holdings of Milt Schwartz and Al Greenfield. Wiggins received a lot of mentions by Down Beat and Metronome reporters in the immediate postwar years, as he led a hot hard-playing combo that appealed to their jazz sensibilities.

Wiggins built his combo up from a trio, with several personnel changes along the way. In May 1944, Phil Featheringill noted in his "Chicago Telescope" column in Metronome that "Eddie Wiggins trio at the Drum on Dearborn features fine drumming by Wally Hock and piano by Rudy Kerpays.... Eddie and Rudy left the [Boyd] Raeburn band in N. Y. in order to form this trio..." (p. 14). At the beginning of 1945 Wiggins was working with Hey Hey Humphries on drums (until Humphries was sidelined after injuring his hands on a glass door) and "young guitar wizard" Joe Rumoro (see Featheringill's column in Metronome, March 1945, p. 10). In the summer of 1945 Wiggins was working the Zebra Lounge on 63rd Street ("Chicago Band Briefs," Down Beat, July 15, 1945, p. 4).

In November 1945 the Wiggins group consisted of himself on alto sax, Jack Fonda on bass, Frank Gassi on guitar, Steve Varela on drums, and Gene Russell on piano. In December 1945, after it had expanded to a sextet, Phil Featheringill said of this group, "Have you caught the Eddie Wiggins band at the Brass Rail on Randolph Street since he added Red Cody on vibes?...the band jumped before and now it jumps even more...Wiggins' crew has a sponsored airshot beamed at high school 'hep-cats' and the broadcast we caught had the soxers dancing all around the stand."

Frank Gassi, who played guitar in Wiggins' combos from 1945 to 1947, was born in Utica, New York in 1909. He was married to Christine Randol, who worked the clubs regularly from 1946 through the early 1960s as a singer/pianist, and recorded for Vitacoustic in 1947 (one single would appear in 1949 on Old Swing-Master).

The Wiggins group would continue into 1946, and Featheringill hinted at the Sultan recording session in his June 1946 column: "Is it true they recently (and at last) were waxed by a new recording company?" The next month, Wiggins had left the Brass Rail for a gig at the Aquarium in New York. Down Beat for July 29, 1946 listed the same personnel for the Aquarium band that Wiggins had used back in December 1945. So we will assume that this same group recorded for Sultan. (Existing discographies include no personnel for this session.)

Metronome in its October 1946 issue had nice things to say about the Eddie Wiggins sides, including the leader's multi-instrumental talents: "This little band from Chicago, which opened at New York's Aquarium last month, jumps healthily in 'Onyx,' with good solos by alto and vibes and some spirited riffing. Nothing sensational here, but very good for an unknown band of which you expected nothing. 'Orientale' shifts the alto man to oboe for a performance that sounds alarmingly like its title and is a weird mixture of exotic sound effects and jump piano. It gets better as it goes along and turns out to be a fast blues, then back comes that oboe."

Toward the end of the year, Wiggins and combo recorded for the Bullet label (whether they did so in Nashville, where Bullet was headquartered, or in Chicago, where the Melrose brothers occasionally steered acts to the company, remains unsettled). The session produced one release, on Bullet 1000, which was released in January 1947. On January 10, 1947 Billboard announced that "Morton Sultan, Sultan Record Company, has taken over distribution of Bullet Records for Michigan and a portion of Ohio" (p. 17). Coincidence?

The Bullet 1000 series—which gets less attention today than the label's 250 R&B series—included a few jazz releases, but after Bullet 1001, by Francis Craig, scored a hit the series was taken over by pop vocalists. Bullet 1000 coupled an instrumental titled "Bullet Bounce" (intended to lanch the series, it featured Wiggins' alto sax solo and Cody's vibes) with a vocal number, "Baby, Know You Like It That Way" (sung by Gassi). Billboard raved about the sides, but they went nowhere and were soon dropped from the Bullet catalogue.

Wiggins occasionally worked on the South Side, for instance when his trio with Red Cody on vibes and Barrett Deems on drums was at the Crown Propeller Lounge, along with a vocal ensemble called the Zany-acks ("Chicago Band Briefs," Down Beat, August 25, 1948, p. 5). This gig lasted till late October:

"The Crown Propellor [sic] has Red Cody, Barrett Deems, and Eddie Schum, plus the four Music Makers with singer Gloria Gale.

"Eddie Wiggins, formerly with Cody and Deems, moved into the Riviera, replacing the Floyd Bean trio, with veteran Oro (Tut) Soper on piano and Jimmy Kilcran on drums. Wiggins, of course plays almost every reed instrument in existence, and all well" (Pat Harris, "Chicago Band Briefs," November 3, 1948, p. 4).

If challenged to back up this claim, Harris could have pointed to a photo that ran in another issue of Down Beat, which showed Wiggins holding a Heckelphone nearly as tall as he was. We can't think of another jazz musician who ever took up the Heckelphone, a baritone oboe that is called for once in a long while in 20th century classical music.The contrabass sarrusophone has a longer jazz discography.

Down Beat continued to put in a good word about Wiggins from time to time. In Pat Harris' "Chicago Band Briefs" for March 25, 1949, we learn that Wiggins was still working the Riviera.

Saxophonist Wiggins has kept pretty close to the alto at the Riviera, although Beat readers may remember a photo used when he was at Jump Town, with eight reeds and woodwinds lined up in playing order ready for the Wiggins touch.

Even when Eddie's feeling low, and deprecatory about the quality of his music, he has an approach and tone that would be hard to duplicate. And what else do you have to have?

With Wiggins are Tut Soper, piano, and George Grunditz, drums, replacing drummer Jimmy Kilcran whose teaching load at the Knapp school was getting to be too much to combine with a full-time playing job.

Wiggins continued on Randolph street into the early 1950s, playing for instance at the Band Box (still at 54 West Randolph in the basement below the Brass Rail). His former guitarist, Frank Gassi, died in an accident in February 1952; he was electrocuted while working on the El. In 1955, Wiggins cut what appears to have been his last record, a 45 rpm single for the Disc-Co and Beam labels; it paired "Wabash Blues" with "Manteca." (On Beam 7001, "Wabash Blues" carried the matrix number F7OW-8090 and "Manteca" carried F7OW-8091, indicating mastering and pressing by RCA Victor in 1955.) We wouldn't mind hearing the single, but by all indications it is extremely rare.

Wiggins continued to perform during the 1950s, usually with a trio. For instance, in December 1957, Eddie Wiggins, Joe Paris, and Duane Thamm were playing Wednesday nights and weekends at the Ain el Turk, a club on Division Street (Chicago Tribune, December 8, 1957, pt. 7 p. 10). During the 1960s Wiggins began a second career as a standup comedian, often appearing as a character called "South Side Louie" on Jonathan Brandmeier's radio show. He also performed as a blues musician under the name of E. C. Williams. Wiggins died on March 29, 1995, in Chicago. His jazz career never took off, despite consistent, strong support from the jazz scribes.

Sources used on Eddie Wiggins: Phil Featheringill, "Chicago Telescope," Metronome, May 1944, p. 14; Phil Featheringill, "Chicago Telescope," Metronome, October 1945, p. 14; Phil Featheringill, "Chicago Telescope," Metronome, November 1945; Phil Featheringill, "Chicago Roundup," Metronome, June 1946, p. 40; Don [Haynes], "Chicago Band Briefs," Down Beat, 29 July 1946; Record Reviews, Metronome, October 1946, p. 34; Pat Harris, "Chicago Band Briefs," Down Beat, 25 August 1948, p. 5; Pat Harris, "Chicago Band Briefs," Down Beat, 25 March 1949, p. 4; "Eddie Wiggins, 78; Jazz Musician Who Later Did Standup Comedy," Chicago Tribune, 8 April 1995. We are indebted to Vince Gassi (emails to the authors, August 14 and 15, 2004) for information about his uncle Frank, and to Chuck Wiggin (phone conversation, February 13, 2014) for information about his father's single on the Disc-Co and Beam labels, and for confirming that "Wiggins" was a stage name.

We thought we had run out of things to learn about Sultan Records, but there are surprises in old trade papers. "Chet Noble [sic] Trio, currently at the Canity [sic] Show Lounge, Chicago, and featuring Boyce Brown, alto saxman, has been signed by the new Sultan Recording Company, of Detroit, and cut its first four sides last week" (Billboard, July 6, 1946, p. 40). If the item was approximately right—approximate is all it could be—Sultan conducted at least one further recording session in Chicago. But a 72-year-old trail is terribly cold.

It stayed hidden so long because of two typos: Chet Roble was a white pianist who had been on the Chicago scene for more than a decade, including a long run at Helsing's Vodvil Lounge, and the Vanity Show Lounge was a joint that Sonny Thompson had recently played. A Detroit stringer for Billboard wasn't having the best of days.

Better late than never. Chet Roble was born Chester Wroblewski, on April 13, 1908 in Chicago. He was given piano lessons as a form of physical therapy after he broke his arm. He became a professional musician in 1932, spending 18 months on tour with Ace Brigode. For a while, Roble, Boyce Brown, and drummer Earl Wiley worked the Liberty Inn, a strip joint. After service in the bands of Gray Gordon, Henry Gendron, and Carl Schreiber, Roble got a job as a solo pianist in 1940 at Helsing's Vodvil Lounge, which, as the name indicated, used the variety-show format. In June 1944, Boyce Brown joined the new sextet that Roble had been asked to form at Helsing's; it enjoyed at least 24 weeks there. A recording of the Roble sextet has survived, on which they play 3 tunes; according to John Steiner, it was made at the Myron Bachmann studio. (We're indebted to Derek Coller, "Chet Roble: A Chicago Pianist," Storyville 149 [March 1992], 164-168, for almost everything we'll be saying here about Chet Roble, including his sextet records.)

Boyce Brown was born in Chicago on January 16, 1910. He barely survived birth, losing one eye and suffering damage to the other along with skeletal deformities. His manner of reading music was to bring each page up to his face, once; he would consult his photographic memory for the rest. He had perfect pitch and synesthesia, experiencing different colors while hearing different chords. He took up the alto saxophone at 14, because a doctor thought it would help him strengthen his chest, and got his first gig in 1927, at a speakeasy run by Bugs Moran and owned by Al Capone. His first surviving recordings were done in 1935 with Paul Mares and his Friars Society Orchestra. Brown also recorded for Decca in 1939 with Jimmy McPartland. In 1940 he appeared on a rare 78 for Mel Henke's private label, Collector's Item; the single may have been his own project. From an extensive private recording session at Gamble's recording labs in 1940, which involved Pete Dailey, Boyce Brown, and Frank Melrose, 18 sides have survived and have finally seen issue on Kansas City Frank Melrose: Bluesiana (Delmark DE-245, a CD released in July 2006). Brown also appeared on a 1945 session for Signature, never released and likely lost. The records he'd made for John Steiner were among those destroyed in the Uptown Playhouse fire in 1946. Boyce Brown worked with white Dixieland musicians, such as Wingy Mannone and Danny Alvin, but often had to settle for employment at strip joints, notably the Liberty Inn and the Silver Frolics.

After the sextet broke up, Chet Roble started a trio at Helsing's, around August 1945. From the sextet, he kept Boyce Brown, and added bassist Sammy Aron. A chronology of the trio's engagements was included in Derek Coller's article in Storyville 149, p. 168. The trio was at the Vanity Show Lounge in July 1946.

Chet Roble (p); Boyce Brown (as); Sammy Aron (b); poss. ens. voc.

Chicago, c. July 1, 1946

| unidentified titles | unissued |

The Southeast Economist for October 24, 1946 (p. 33) had the trio playing the Delta Lounge and credited Sammy Aron with playing accordion and guitar. However, in every other bit of coverage that we've seen, Aron was identified as a bassist.

While no one questioned his "piano bar personality," opinions differ as to how much of a jazz musician Chet Roble was. But his trio got pretty consistent plaudits from the jazz scribes. Coller mentions no gigs between October 1948 and May 1949, but in January 1949, the original trio was working in Rock Island, Illinois (Daily Dispatch [Moline, Illinois], January 28, 1949, p. 8), and, name changed to the Barefoot Bunch, they were back in Chicago at the Cairo in February ("They've been playing in the hinterlands"; Will Davidson, Chicago Sunday Tribune, February 27, 1949, section 8, p. 4). In May 1949, Boyce Brown was replaced by Charlie Spero. In June the Barefoot Bunch was appeared at the Hunt club in a western suburb (Will Leonard, "Folk Song Famine Over," Chicago Tribune, June 21, 1959, pt. 7 p. 11; if Leonard's recollection can be trusted, Roble was temporarily leading a septet.) Roble's trio broke up for good early in 1950; in April Roble was at Helsing's again, singing and playing piano. After leaving Helsing's in 1951, he worked cocktail lounges for a few months. In December 1951 he landed a job at the main piano bar in the Sherman Hotel, where, with some brief interruptions, he would spend nearly 11 years.

Roble made some TV appearances, most notably on Studs Terkel's show Studs' Place, which ran on WENR in 1951. In May 1952, featuring his singing, he cut a pop single for a tiny company called Topper, with a studio ork conducted by Dennis Farnon (duly noted on intake as Topper 202, Billboard, June 28, 1952, p. 39, and given a tepid review on p. 38; reviewed in Cash Box, same date, p. 32). Topper was a short-lived operation run by Rick Noran and Jack DeSort. Lee Egalnick, plugging two tunes from Premium Music, had a hand in its final release, in September of that year (until 2018 the only Topper we knew of was this last one, 204 by Freddy Cole). For that matter, "Barefoot Boy" on Topper 202 was published by Premium Music.

Later, Jack Tracy produced an LP, Chet Chats: Argo LP-616. It has been described as a 1958 release. An item in the Chicago Tribune (September 22, 1957, part 7 p. 12) announced it was "set for next month." But the back of the LP says it was recorded on December 10, 1957, and mentions Argo releases up to LP 635. Roble played and sang in a quartet setting; Tracy didn't consider it jazz, exactly. (Coller said the LP was done in 1953, but Argo wasn't in business in 1953. Someone did some showbiz fibbing about Chet's age, and five years got shaved off it in the notes.)

Chet Roble died of a heart ailment on October 31, 1962, aged just 54 ("Pianist Chet Roble; Vet Chicago Favorite, Billboard Music Week, November 24, 1962, p. 6). He was survived by his estranged wife Ginnie, who was Bill Reinhardt's sister.

In 1952, Boyce Brown converted to Roman Catholicism. He was serious about it; in 1953 he joined the Servite Order as a monk. As Brother Matthew, he made an LP in New York for ABC-Paramount in April 1956; ABC-Paramount 121 was reviewed in Billboard and Cash Box on May 12. Proceeds were to go to missionary efforts in South Africa; the session was organized by Eddie Condon and by one of Brother Matthew's superiors in the order, Father Hugh Calkins. Life magazine ran a spread on the session and Brown even got a couple of TV appearances out of it.

Because he was suspected of drinking more than was acceptable in the monastery, Brown eventually realized that he would not be permitted to take final vows with the Servite Order. Brother Matthew suffered a heart attack and died at the monastery at the age of 48, on January 30, 1959.

See Hal Willard, "Boyce Brown: Jazzman in Two Worlds," Mississippi Rag, February 1999; online at https://jazzlives.wordpress.com/2011/10/27/boyce-brown-jazzman-in-two-worlds-by-hal-willard-1999/; Willard, in our opinion, exaggerates the proportion of his career that Brown spent playing in strip joints. And see "Blues for Boyce" (August 24, 2011) on the Jazz Lives website: https://jazzlives.wordpress.com/2011/08/24/blues-for-boyce/#comment-45451.

The last mention of Sultan signing anyone was published on August 3, 1946 ("Sultan Sets Two," Billboard, p. 35). Using the opportunity to spell Chet Roble correctly, the item also mentioned a pop singer: "Gene Newcomb, bary who caught some eyes as a G.I. with the Camp McCoy, Wis., bond-selling shows." Was Sgt. Sultan talked into accompanying him? "Early releases are planned." Were they?

In January 2007, we learned of a fifth (?) Sultan release—also sporting a copyright date of 1946, but recorded in Detroit. Collector Tony Berci reported a Sultan in a 1000 series; the labels use the same design that we know from the 2500s, but in black on yellow instead of silver on black. Sultan 1000 featured Cantor Hyman Adler of Congregation B'nai David. Hyman J. Adler was born on April 9, 1911. When he recorded for Sultan, B'nai David was located in Southfield, Michigan. A second 1000 series Sultan came up for sale in 2016: Sultan 1001, also by Cantor Hyman Adler (release number six, maybe). The cantor's Sultan 1003, which turned up for sale in 2014, was the product of a deal with another company, but the Sultan label design was still employed, minus the copyright. We include it here, but won't count it as a genuine Sultan.

Hyman Adler (voc); other musicians unidentified.

Detroit, 1946

| Hatikvah | Sultan 1000A | ||

| Ich fur Aheim | Sultan 1000B | ||

| Papirossen | Sultan 1001A | ||

| Mein Shtetele Belz | Sultan 1001B | ||

| Passover Medley (1) | Sultan 1003A | ||

| Passover Medley (2) | Sultan 1003B |

"Hatikvah," sung in Hebrew, would soon be the national anthem of Israel. On May 16, 1948, when Israel declared its independence, there was a public celebration in Detroit. Cantor Adler didn't sing "Hatikvah," but he blew the shofar. "Ich fur Aheim" was a Yiddish-language popular song.

On April 10, 1948, Billboard reported that 24 sides by Cantor Hyman Adler had changed hands: "Plate Distributing Company, headed by Kal Bruss, dips into the specialized field of Jewish disks with acquisition of a series of 24 masters by Cantor Hyman Adler" (p. 39). The source was not mentioned; presumably Morton Sultan didn't want people to think he was giving up on his company.

Sultan 1003 was obviously a product of this deal. The words "A Bruss Recording" have been added to the labels, and "Distributed by Planet Sound - Detroit" has replaced the old Sultan copyright. We have not listed the other masters (we don't know any specifics on them) but will add them if more 1000 series Sultans (or Bruss-Sultans) turn up.

We doubt that Kal Bruss sold a lot of the cantor's records. He closed Planet Sound after a couple of years: "Kal Bruss, formerly with Planet Records here, has returned to the motion picture business as salesman for Lippert Productions in up-State Michigan" (Billboard, March 1, 1951, p. 33). Bruss went to greater success as a regional publicist for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and an executive at a Michigan movie theater chain. Hyman Adler died on March 15, 1992.

Then in August 2018, we learned of a seventh release on Sultan (the numbering is, as always, contingent on something really happening with Chet Roble). An eighth, by the same artist, turned up in December 2019. These were in yet another short series, the 5000s for Country and Western. Courtesy of the 45worlds.com site, we also have label copy for the releases. We've learned that something different was stamped into the trailoff, at least on 5001 (see below). The 5000s used a silver on blue Sultan label.

Lawton "Slim" Williams (1922-2007) got two singles out as Sultan 5000 and 5001. The location and date have been given as Detroit, 1947. Since Williams' next recording was in Detroit, for Fortune in 1949, the placement works. However, Craig Maki (email of March 10, 2025) has pointed out that, after his discharge from the armed forces, Williams traveled to Chicago with Lee Penny, who had been an A&R man for Mercury. Penny now learned that was no longer with Mercury, so Williams wouldn't be getting a contract with that label. If either of them was in contact with the label's owner, Williams and Penny could have done a session in Chicago for Sultan. In Williams' later recollections, he left for Detroit, where his cousin Jack Luker led a band, as soon as he learned there would be no Mercury deal. But Williams also remembered his sides for Fortune as his first recordings.

The personnel for the date is also dependent on where it took place. In Chicago, Williams would have used Penny and a studio group. In Detroit, he would have been using members of Luker's band, or other musicians he had started working with.

Lawton "Slim" Williams (g, voc); other musicians unidentified.

Detroit or Chicago, 1947

| Fire Water (Williams & Brunner) | Sultan 5000A | ||

| Have Mercy on Me (Lawton Williams-Babe Fritsch) | Sultan 5000B |

Sultan 5000 appears at the first entry in PragueFrank's discography for Lawton Williams at http://countrydiscoghraphy2.blogspot.com/2016/06/lawton-williams-slim-williams.html. See also http://countrydiscoghraphy2.blogspot.com/2016/04/lawton-williams-by-dick-grant.html. Label photos are at https://www.45worlds.com/78rpm/record/nc093339us. We have made a couple of corrections to the label copy; for instance, Williams was not called "Slim" on his Sultans. Sultan 5001 (label photos at https://www.45worlds.com/78rpm/record/nc218333us) is surely from the same session. We learned the matrix numbers on Sultan 5001 (which were, indeed, stamped in the trail-off area) from Craig Maki (email communication, February 11, 2025). They seem to belong to same series as S106 through S115 (above). Were S116 through S130 once reserved for Cantor Hyman Adler?

Lawton Williams was born in Troy, Tennessee, on July 24, 1922, and picked up the guitar in his teens. While serving in the Army in World War II, he met Floyd Tillman, who encouraged him to take up a musical career. The Sultans were his first two singles. After recording for Fortune and other small labels like 4 Star, Williams landed a contract with Coral in 1951. Lawton Williams was a Country traditionalist who wrote more hits than he recorded. His full catalogue runs to 240 songs. Williams did not record an LP until 1971, but remained an active performer at country music venues until shortly before his death in Fort Worth, Texas, on July 27, 2007. He was 85 years old. See the obituary in Dave's Diary for July 31, 2007: http://www.nucountry.com.au/articles/diary/july2007/310707_lawtonwilliams_obit.htm.

Sultan Records is, on the whole, a mystery. It was important to Morton Sultan, but we don't know what prompted him to open it. And there was no lack of musicianship in Detroit. For example, pianist and bandleader Todd Rhodes, who would record extensively for Sensation and Vitacoustic beginning in 1947. T. J. Fowler, another pianist, led an excellent combo that got few opportunities to record. Some of the jazz musicians then active in Detroit became nationally known. Did Sultan have a business relationship with Joe Sherman of the Garrick Lounge, or Milt Schwartz and Al Greenfield of the Brass Rail and Band Box, or even with the proprietor of the Vanity Show Lounge?

What we have learned is that Morton Sultan kept reaching, for more than four years, for some kind of toehold in the music business—including, if at all possible, a revival of his record company.

He didn't stay in the Penobscot Building. The rent was too high: he'd been sharing his street address with Pan American Airlines and the Detroit bureau of the Philadelphia Inquirer. From August 1946 through March 1949, Sultan was doing all kinds of things.

He tried becoming a booking agent: "Sligh & Pheasant, Chicago bookers, opening branch office here, to be managed by Morton Sultan Recording Company..." (Billboard, November 9, 1946, p. 40).

He tried promoting dances: "A deal to stage weekly one-nighter dances for the winter season in the Eastwood Park Ballroom, not regularly used for dancing for several years, is under discussion. Promoter Morton Sultan, head of the Sultan Record firm, is dickering for the spot" ("Detroit Ballroom Likely to Get One-Nighter Season," Billboard, August 9, 1947, p. 41).

With his brothers Henry and Aaron, he invested in something called Sultan's Driv-A-Teria (Billboard, August 30, 1947, p. 113).

He bought a recording studio. J. Hall Smith had been running a transcription studio on the top floor of the Union Guardian Building, 500 Griswold. Smith took a job with WOAP radio in Owosso, Michigan, and sold the studio to Mortan Sultan. Sultan was moved his record company into the building as well ("Morton Sultan Takes Over Tower Top Transcription," Billboard, November 1, 1947, p. 39). A couple of months later, Billboard annnounced "Morton Sultan, of Sultan Records, opened a new studio on the top floor of the Union Guardian Building" (January 17, 1948, p. 101).

James Caesar Petrillo's reach didn't extend nearly so far in Detroit as it did in Chicago, but two weeks after the start of a recording ban wasn't an auspicious date for opening a studio. Another one-sentence item non-coincidentally stated: "Morton Sultan has revived the Sultan Record label, dormant for several months, with a whole stable of recordings in the foreign language and hillbilly fields" (Billboard, January 1, 1948, p. 35). The sides, we are confident, had been made already. Foreign languages: Hebrew and Yiddish (Cantor Adler). Hillbilly: Lawton Williams. On January 24, Billboard gave the Union Guardian Building as the address for Sultan Records (Juke Box supplement, p. 9).

Morton Sultan unloaded the Cantor Adler sides to Kal Bruss in April (see above). He tried selling recording equipment: "Morton Sultan, owner of the Sultan label, is establishing a new line of recording equipment, under the name of Recorder Sales Company, in addition to his disk operations" (Billboard, May 22, 1948, p. 45). Did the demonstrator models come out of Tower Top Recording Studio?

Three weeks later, Sultan Distributing was gone. Shortly after setting up the distributor, Morton Sultan handed over its managment to his partner Sidney A. Verier. By the end of 1947, its lunch had been eaten: Idessa Malone and Pan-American had been making serious incursions into the R&B market. With the closure Verier was out of the record business (maybe he'd also relinquished his partnership in Sultan Records). Guess who picked up what was left? "Manor and Gala, principal disk lines handled by Sultan, are being taken over by Pan-American Record Distributors plus the remainder of the old Sultan stock" ("Sultan Distrib's Shuttering Makes Second Recent Close," Billboard, June 12, 1948, p. 20). In the distributor directory that ran in Billboard on July 19, 1948, a label called Ultra that had forgotten to update was the only one that mentioned Sultan (NAMM Supplement, p. 57). At the next annual meeting of the Michigan Record Distributors' Association ("Michigan Distribs Blueprint an Org," Billboard, March 19, 1949, p. 19), Verier was replaced on the organizing committee by Casey Jones from Idessa Malone Distributors.

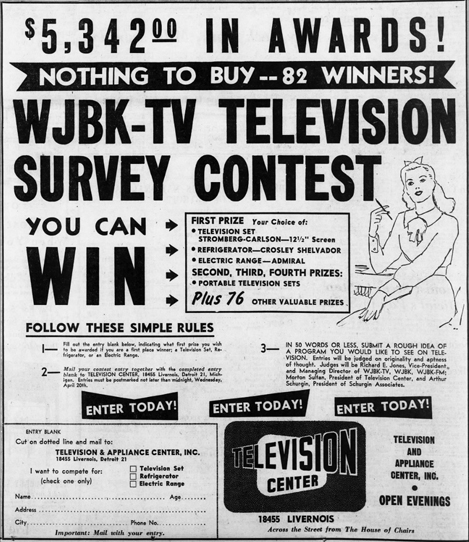

There probably hadn't been any Sultan releases in 1948; there definitely weren't any in 1949 and 1950. Yet Sultan Records was still appearing in Billboard. These weren't ghost listings left by failures to update; the street addresses kept changing. Was the owner sitting on old inventory, like Nathan Rothner at Hy-Tone? But Sultan Distributors had unloaded its inventory to Pan-American. Was he waiting for an opportunity to resume recording that never came? In Billboard's directory from January 22, 1949 (p. 72), Sultan's address was given as 5110 Stanton Avenue, which had been a refrigerator warehouse, and at that date could have have been an appliance store. (A real ghost listing in the same issue went to Sunbeam—at the address where it had been when it closed in November 1947.) In the directory from July 15, 1950, Billboard gave the address as 18455 Livernois (p. 74). That was the Detroit Television and Appliance Center.

In March 1949, Morton Sultan opened the Detroit Television Center at 18455 Livernois (the first Detroit Free Press ad appeared on March 20, Sec. E p. 3). He gave every sign of being in transition from the appliance business: on March 31, the Television and Appliance Center was moving out its inventory of refrigerators, stoves and washers "Below Wholesale" "MAKING ROOM FOR TELEVISION" (Detroit Free Press, March 31, 1949, p. 31). On April 17, 1949, Sultan joined up with WJBK-TV to put on a big promotion. Customers were asked to write an idea (in 50 words or less) for a new TV program. A panel of three judges including Morton Sultan, "President of Television Center," would award the prizes, which included new television sets and new kitchen appliances remaining in inventory.

By October, the store's ads were pushing payment plans of 25 cents a day, no money down (Detroit Free Press, October 9, 1949, Sec. E p. 2). Such promotions continued through December 7. On December 11, 1949, a new location was added (9330 Grand River, formerly an army surplus store) and the promotion became "Buy Television on the Meter Plan" (Detroit Free Press, Sec. E p. 2). On February 12, 1950, "Refrigerators on the Meter Plan" were added (Detroit Free Press, Sec. E p. 3). The last ad we've found read "WAR | We're Out to Capture the TV Market" and ran on March 26, 1950 (Sec. E p. 6). One senses the direction. The Detroit Television center couldn't pay its bills and a few months later it defaulted on a chattel mortgage. On September 19, 1950, after the wholesalers had retrieved their TV sets, remaining assets were sold at auction. Under the gavel went television meters, parts, testing equipment, accessories, office furniture, a delivery van (Detroit Free Press, September 17, 1950, Sec. E, p. 8). The saddest part read: "Freed Eisman 16" Console, Recording Machine, Inter-Com Boxes, Presto K-8 Recording Machine."

That same year, there was a Sultan imprint based in Natchez, Mississippi. No question about its being a completely different operation. The two Sultans happily coexisted in Billboard's listings from 1950 to 1952.

In its directory for July 14, 1951, Billboard put Sultan at 5182 Grand River in Detroit (p. 69). Early the next year, the same address (Billboard, March 15, 1952, p. 129). 5182 Grand River for many years was the site of a gas station, close to Grand River Chevrolet. Was the Drive-A-Teria the last of Morton Sultan's late-40s business ventures?

We don't know what kind of work Morton Sultan did for the next 15 years. His father had retired, so we don't think he was selling Chevrolets. We don't know how long he held onto the Drive-A-Teria. In the 1960s, several Sultans migrated to California. Louis Sultan moved to Los Angeles in 1964; he died there on July 17, 1967 at the age of 81 ("Louis Sultan, Retired Car Dealer," Detroit Free Press, July 19, 1967, p. 9B; his obituary ran next to John Coltrane's). Sultan Realty, in Van Nuys, was advertising in The Valley News for October 27, 1967 (classified p. 2). Morton may have partnered with one or more of his brothers, but their names were never mentioned in publicity. Henry Sultan, MD, died in Southern California a few years later (Los Angeles Times, January 31, 1972, Part II, p. 4). When Fannie Sultan died, her funeral service was held in Southfield, Michigan, but she was buried in California (Detroit Free Press, January 10, 1977, p. 3-C).

In 1973 Morton Sultan was running two Sultan Realty offices, one in Van Nuys and one in Simi Valley, and in 1974 one of his associates was inducted into the two million dollar club. In 1976, there was one Sultan Realty office, at 4785 Los Angeles Avenue in Simi Valley. The last Sultan Realty ad we have spotted appeared in the Los Angeles Times on March 30, 1978. In November 1977, Morton Sultan, 7533 Eaton, Canoga Park, California, was operating Tri-Valley Construction at an old address for his real estate firm, 7232 Sepulveda Boulevard in Van Nuys (Valley News, November 27, section 2 p. 4), and he soon opened Tri-Valley Investments out of the same address (Valley News, December 27, section 2 p. 7).

Morton Sultan died in Los Angeles on December 31, 1983. On January 25, 1984, his brother Aaron posted a legal notice of his petition to administer Morton Sultan's estate (Newhall Signal and Saugus Enterprise, p. 32). In 1985, his son Robert petitioned to take over, probably because Aaron had also died. The last of the four Sultans, Lottie Colton, died on March 13, 1998 at the age of 89 ("Lottie Colton: West Bloomfield Resident, Pianist," Detroit Free Press, March 15, 1998, p. 28).

Sultan Records was no more than a failed experiment. Yet the company had picked worthwhile artists to record. Eddie Wiggins wasn't so lucky, and basically ran out of recording opportunities after 1946. Red Saunders would record steadily over the next decade, and Sonny Thompson would move on to a long and rather successful career in the business. Chet Roble and Boyce Brown also got further chances to record, though not as many as either deserved. Lawton Williams would enjoy moderate but durable success in his line of music.

Our thanks to Lars Bjorn (coauthor of Before Motown, the definitive history of jazz in Detroit) for pointing us to the June 1946 article in Metronome; to Dan Kochakian for a copy of Sultan's advertisement in The Billboard, as it was then known; and to the late Eric LeBlanc for birth and death dates on Eddie Wiggins (who is listed in Social Security records as "Wiggin") and Morton Sultan. During his lifetime, there was just one Morton Sultan of any prominence anywhere in the United States, so the growth of newspaper archives online has done the rest. The late George Paulus, Tom Kelly, and Daniel Gugolz proivded label scans and matrix information on some pretty rare 78s in the 2500 series. Daniel Gugolz's copy of 2503 has the -2 suffixes on the matrix numbers; George Paulus' copy sports the -1s. Tony Berci unearthed Sultan 1000; since then, two further releases in the series (1001 and 1003) have shown up on Popsike.