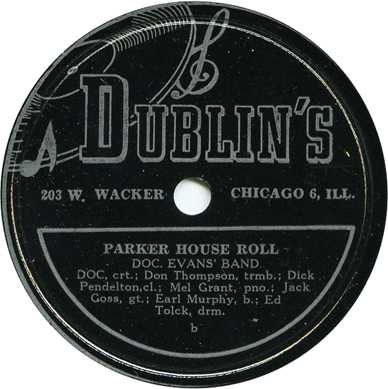

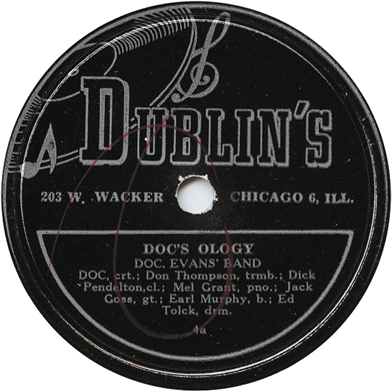

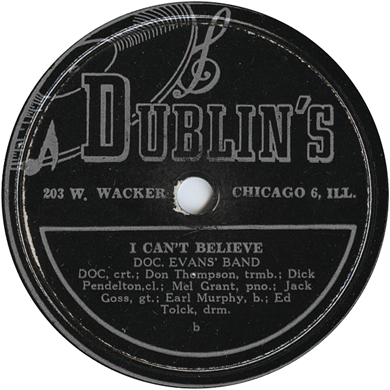

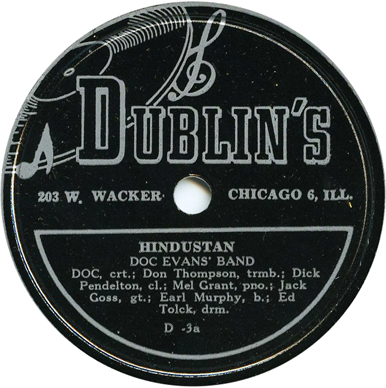

Revision note.Anthony Barnett has recently updated his information on the "Rehearsal" side from the Red Norvo-Stuff Smith session of April 5, 1944. S D 5002 A was put together from master 4544-00 (with about a minute edited out) and another master that apparently has been lost. We have added matrix details from the Paramount 10-inch LPs in the collection of Konrad Nowakowski; they appear to contain clues about the mastering and pressing. We have recently obtained scans of the remaining correspondence between John Steiner and The Bishop Presses (a California pressing plant he used between December 1946 and September 1950 for S D and Paramount 78s). Steiner retained most of his correspondence with Bishop, which enables us to identify release dates for several S D and Paramount items, and to give us a better sense of the quantities pressed (low, as a rule). The correspondence takes up Box 26 Folder 22 in the John Steiner Collection, which is part of the University of Chicago Library Special Collections. We are still adding information about Steiner's first LPs. No Label (they used a silver on black label with no logo) 1 and 2 added up to double LP, titled Informal Session at Squirrel's and released (in a really short pressing run) in 1951. We have updated our listings on the four Dublin's 78s by Doc Evans and his band, and made a note of the strange defect on Dublin's 1b (take 5 of "One Sweet Letter"). It's one of those weird slips, tricks, or substitutions that we've come to call "Steinerizing." We have corrected our discographical listing for Duke Ellington's "Frankie and Johnny" (S D Christmas 46, probably released in March 1948) to reflect its origin in the Civic Opera House concert of March 25, 1945. We have significantly upgraded our coverage of the reissue Paramount singles and Paramount LPs, using original labels that John Steiner kept in his files and are now in the John Steiner Collection at the University of Chicago (more photos are still to beadded). In particular, we have added S D 509 and 510 by Punch Miller.

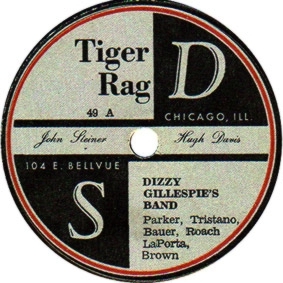

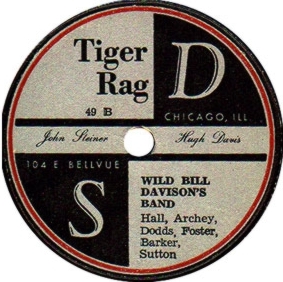

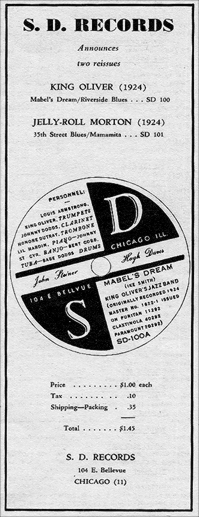

S D Records was the brainchild of two Chicago record collectors, John Steiner and Hugh Davis. As with most collector jazz labels of the period, S D focused on reissuing vintage jazz recordings from the 1920s and 1930s and new recordings either by artists from that period or by younger artists who played in a traditional style. The company was founded in January 1944, but Steiner and Davis had already been working together for four years, recording music in the city, occasionally also in Milwaukee, at various homes and on location in clubs. The label's original headquarters were at Steiner's home, at 104 East Bellevue Place. Steiner and Davis departed from usual business model for a collector label: they did not operate a record shop to help support it, although both bought and sold extensively in the collector market. For a while in 1946, Steiner ran the company out of an office in the Uptown Playhouse Theater, 1225 North Lasalle. After the theater burned down in April 1946, Steiner ran it from an apartment at 154 East Ontario Street. But in June 1947, when S D was no longer making new recordings but was continuing with its release program, the company's headquarters moved to Chicago's downtown, at 8 South Dearborn. There Steiner operated a "record exchange," essentially a record shop for rare jazz discs.

The partnership after which the label was named survived barely more than a year: in February 1945 Davis sold his half of the company to Steiner (the transaction was announced in Down Beat on February 15). Steiner then operated the imprint on his own for the next five years or more. By the beginning of 1949, he had moved the company once again, to his apartment at 1637 North Ashland Avenue. Because of the trouble they were having getting pressings of reasonable quality at an affordable price, Steiner and Davis had already quit pressing S D 78s in the fall of 1944; a Down Beat item on January 1, 1945 announced that S D was suspending activities "until conditions return to normal."

In mid-1945, the dormant company's address changed to 1225 North Lasalle; i.e., the Uptown Playhouse Theater, where Steiner was actually living while promoting trad jazz concerts and operating other ventures. But Steiner was compelled to regroup after the theater burned down on April 20, 1946.

He resumed recording with a session in September 1946, and made a limited edition S D release available for Christmas of that year. But his activities remained limited; in October 1946, he was briefly allied with Jack Green, who was trying to start a new jazz label (the attempt failed, but some of the recordings ended up on Gold Seal). In December 1946, Steiner found a pressing plant that he trusted; he began using the Bishop plant in South Pasadena, California, which had opened in April 1946. Doing business with Bishop enabled several S D releases that had been held back to finally make it to market.

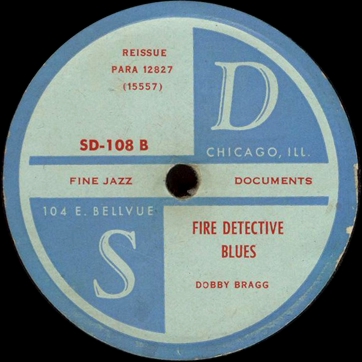

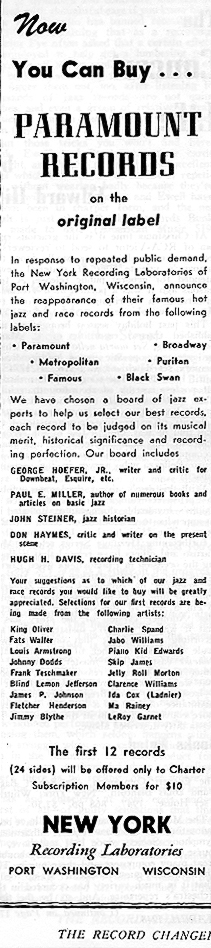

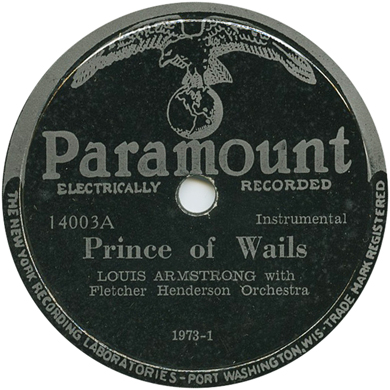

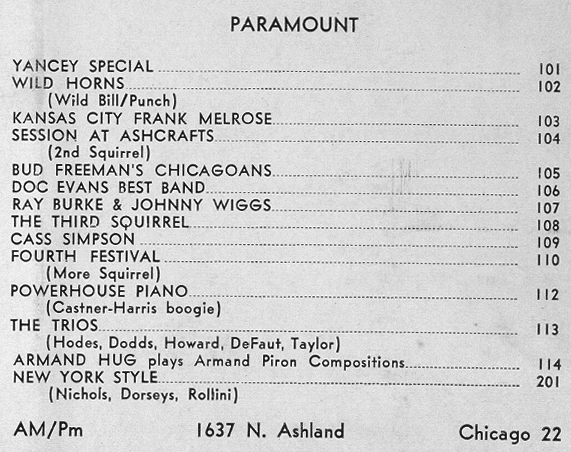

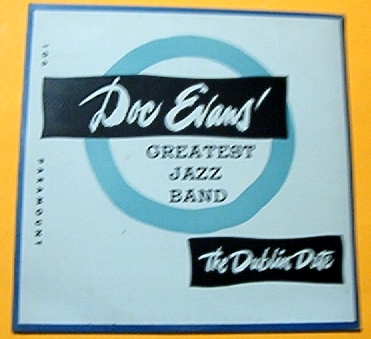

In December 1947, he recorded a session by traditional jazz cornetist Doc Evans for the Dublin's label, operated by a local record store. Around February 1948, Steiner was able to acquire the remnants of the old Paramount label. After a couple of premature announcements in the press, 13 78s on his revived Paramount imprint rolled out in 1949, and 19 more would follow in 1950; Steiner also began producing new traditional jazz material for release on the label. In 1949, he also briefly maintained a Down Beat label (not connected with Jack Lauderdale's enterprise in Los Angeles). Downbeat released 3 78s of jazz material that had been made for Chord, a label run out of Milwaukee that had been in business from the spring of 1947 till the summer of 1948. Meanwhile, sporadic S D releases stretched through 1948 and 1949. Steiner stopped using Bishop to press his records in September 1950, as he got out of producing 78s and geared up for 10-inch LPs.

In Record Changer advertisements for the final S D releases, the company was referred to as Paramount Distributors; its location was Steiner's apartment at 1637 N. Ashland Avenue. From then on, though Steiner sold S D 78s that he still had in stock, the company he ran was called Paramount. Steiner would reissue some of the S D material on 10-inch Paramount LPs between 1952 and 1955; he also revived the S D imprint for one 10-inch LP in 1954.

S D bore many resemblances to another Chicago-based independent, Session. Session, which opened a couple of months before S D, was also founded by ardent record collectors (Phil Featheringill and Dave Bell) with an interest in 1920s jazz and blues. Both labels combined new recordings with reissues (and shared an ardent interest in Jelly Roll Morton); both embraced technical innovations (wire recordings for S D; vinyl pressings for Session); both struggled getting records pressed during World War II, and both relied on The Bishop Presses in Southern California after the war ended; both were undercapitalized boutique operations that often had to delay or abandon planned releases. But after Session closed for good in the fall of 1947, Phil Featheringill and Dave Bell sold off their record collections and got out of the business. Although Hugh Davis bailed in 1945, John Steiner continued with new releases until 1955, well into the LP era, and kept contributing to the study of jazz history long after that.

John Steiner was born July 21, 1908, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. During the late 1920s and early 1930s he was in college, working towards his PhD in chemistry at the University of Wisconsin. On weekends he would head down to Chicago, soaking in city's world of jazz. He also began building a record collection. After getting his PhD in 1933, Steiner became a research chemist and later a university chemistry professor, but of his many passions he is best known for his interest in early jazz. Not only did he collect records, he collected oral histories and promoted concerts of traditional jazz. In 1935, with Helen Oakley (later Helen Oakley Dance) and Harry Lim (later the proprietor of Keynote Records), Steiner founded the country's first hot jazz club. The Hot Club of Chicago (HCC), modeled after the famous French club, regularly sponsored small combo jazz concerts in the city during the second half of the 1930s.

By the 1940s, Steiner was working at Miner Labs in Chicago and thoroughly ensconced in Chicago's traditional jazz community. These being the years of factionalism and polemics, the "moldy figs" were subject to considerable derision from modernists. He was the jazz correspondent for Jazz Information, and contributed to the traditionalist Jazz Session magazine.

Meanwhile, back in 1938, Steiner had met another avid jazz collector with a scientific bent, Hugh Davis. Davis was a native of Wichita, Kansas, who worked as an electrical engineer for a variety of Chicago manufacturing plants. At one point, he worked for the Seeburg jukebox company, doing development. He designed a home recorder for the firm, which they marketed. Together, Steiner and Davis perfected equipment for recording live jazz performances and for dubbing old disks. As early as 1940, they were traipsing around the North and South Sides of Chicago with "several hundred pounds of recording junk" in search of jazz, generally of the traditional variety. With ever-improving technology, the pair recorded jam sessions, solo and band performances, and radio shows. They also dubbed many rare jazz and blues disks, some of which were previously unknown test pressings.

In January 1944, Steiner and Davis founded S D Records to issue the jazz recordings they had been gathering over the previous four years and a series of new sessions they had planned. For the reissue side of their enterprise, Steiner and Davis acquired rights to 24 sides from the old Paramount label, a blues and jazz imprint that had operated out of Port Washington, Wisconsin, from 1917 to 1932. The company's first releases were in the 100 series, which was for reissues. Steiner bragged to Down Beat's George Hoefer, Jr., about S D technical standards:

Nineteen cuttings were made before the four sides as re-issued were picked. We are using a new fading technique using timer ticks twice a second and by starting the records at the same point synchronization of the treble and bass control gives an effect omitting the sizzle on old records.

Steiner and Davis reported that future releases of new material would include piano solos by Jack Gardner and Tut Soper, and combos featuring Punch Miller, Jimmy Dudley, and Wild Bill Davison. Also cited for possible release was a 1940 recording they had made of the Pete Daily Jazz Band featuring Frank Melrose. (A set of 1940 studio recordings of a Frank Melrose band featuring Pete Daily and Boyce Brown finally got its first release on a Delmark CD in 2006, but so far as we know Steiner and Davis were not involved with them.) These performers were thoroughly in the traditionalist camp. Not all of them would actually make it onto the S D label. Some would never appear at all—because the lacquers of their recordings were destroyed in the fire in April 1946—and some would be held for release until 1952 or later, on Steiner's revived Paramount label.

The neophyte label operators assured Hoefer that they had "signed with Petrillo and have union approval on all releases they make," suggesting that the American Federation of Musicians in the past had not been fully supportive of their live recording activities.

Sources used: John Steiner, "Here In Chicago," The Jazz Session 5 (Jan.-Feb. 1945): 3, 22; George Hoefer Jr., "The Hot Box," Down Beat, 1 February 1944; "Disc Exchange Set Up By Steiner," Down Beat, 26 March 1947, p. 13.

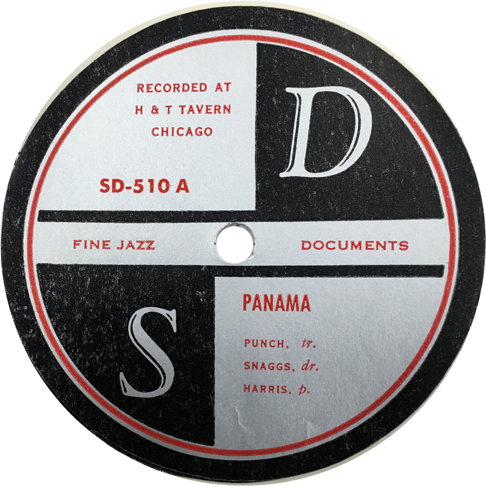

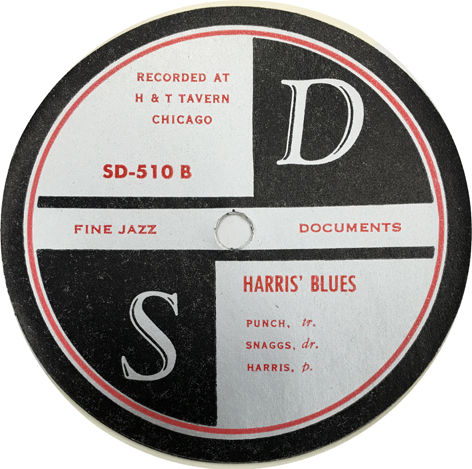

On January 28, 1941, Steiner and Davis had shlepped their equipment to the H & T Tavern to record New Orleans trumpeter Punch Miller. They got six usable sides out of their efforts. Steiner planned to put Punch Miller tracks out on S D, or so it was announced in July 1945, in George Hoefer’s Down Beat column. But the releases were much delayed; for the longest time we thought they had been canceled. However, the John Steiner Collection at the University of Chicago Library includes loose labels to nearly everything that Steiner released, on S D, Paramount, and the other imprints he was associated with. In later years, Steiner would often include a label or two in his return correspondence with historians and jazz collectors. The Steiner Collection includes printed labels to both sides of S D 509 and 510, with a layout seemingly modeled after the labels to S D 507.

The actual release on 509 and 510 could have been delayed as far as 1950. And there's no assurance that even then either side was pressed beyond what Steiner called "experimental lots." S D 509 and 510 were not included in Steiner's 1950 catalogue, in the two booklets that were included with some of the early Paramount LPs in 1952 and 1953, or in the lists on the backs of various of those LPs. We won't know the matrix numbers and we won't know who pressed the records until we see an actual copy.

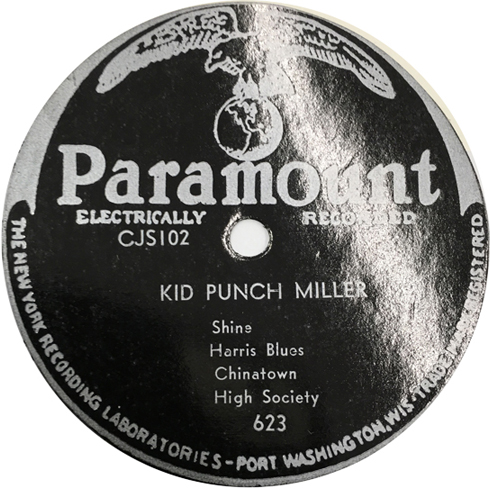

Nearly everyone knows this session from the four tracks from the 1952 LP release on Paramount CJS102— which, it turns out, are not the same four that were originally released.

Ernest "Punch" Miller was born in Raceland, Lousiana (on June 10, 1894 or December 24, 1897, depending on which source you believe). He worked with legendary New Orleans bandleader Jack Carey ("Tiger Rag" was once known as "Play Jack Carey"), and in army bands during his service in World War I. In 1926, he moved to Chicago, where he worked but did not record with Freddie Keppard and Jelly Roll Morton, and did both with Al Wynn. As a member of Tiny Parham's big band, Miller appeared on three of Parham's Victor recording sessions. Victor wanted a cut-down ensemble and Parham alternated Miller on a platoon system with Roy Hobson, who was not nearly so good a jazz player. Miller's sessions with Parham took place in 1928 and 1929. Before the Depression killed off jazz recording in Chicago, he did a session in 1930 with Frankie Franko's Louisianians. Up through the mid-1940s he often led his own bands in Chicago.

Ernest "Punch" Miller (tp, voc on %); Ace Harris (p, voc on #); Clifford "Snags" Jones (d).

H & T Tavern, Chicago, January 28, 1941

| High Society | S D 509 A, Paramount CJS102 | ||

| Bugle Call [Bugle Call Rag^] | S D 509 B, American Music AMCD-40^ | ||

| Panama | S D-510 A | ||

| Harris' Blues | S D-510B, Paramount CJS102, American Music AMCD-40 | ||

| Shine | Paramount CJS102, American Music AMCD-40 | ||

| Chinatown [Chinatown, My Chinatown^] | Paramount CJS102, American Music AMCD-40^ |

After Steiner and Davis recorded him, Miller wandered around the country for a while. He resurfaced in Chicago in 1944, where the rival Session operation recorded him in the studio on June 12. In 1947, he moved his base of operations to New York City, where he would next record for Savoy (two sessions that year). For roughly the next decade he toured in circus bands and R&B combos. After returning to New Orleans in 1956 to participate in the traditional jazz scene there, he recorded fairly often up through 1969, becoming a regular at Preservation Hall, and was featured in a documentary film in 1971. Punch Miller died in New Orleans on December 2, 1971.

Born at 2310 2nd Street, New Orleans, in 1900, Clifford Jones began playing the drums while in elementary school. (His nickname, "Snags," was a slightly more decorous version of "Snaggletooth.") His first professional job with was with the legendary (and completely unrecorded) cornetist Buddy Petit. Subsequently Snags worked for several years in Jack Carey's band and also gigged with Papa Celestin and A. J. Piron. In 1922 he joined the migration to Chicago, where he initially worked under another New Orleans expatriate named Tig Chambers. In 1924 he was a member of King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band while it still included Louis Armstrong. He made his first records in 1926, providing accompaniment for blues singers with Richard M. Jones at the piano. In 1928, he recorded with Junie C. Cobb, Jimmy Wade, the Dixie Four, and the State Street Ramblers. After a sojourn in Milwaukee, he labored in relative obscurity in Chicago for most of the 1930s.

After appearing with Punch Miller on Session, Snags recorded with Preston Jackson for Victor (October 31, 1946; two of these sides featured him as a blues singer); during that same year he worked with Darnell Howard and Bunk Johnson. He died in Chicago on January 31, 1947.

In their recordings of live sessions, Steiner and Davis were partial to piano players. This was partly out of personal interest—Steiner was a proficient amateur pianist whose jazz styling revealed a heavy Earl Hines influence. There was also the financial angle—a solo piano player was more economical than a combo. Consequently, there were recordings by Cow Cow Davenport, Jack Gardner, Tut Soper, Cassino Simpson, Mel Henke, Chet Roble, and Frank Melrose. Still, most of these sessions did not end up on S D. One reason is that many of the live concerts Steiner and Davis recorded in the 1940s were done on 16-inch discs, often yielding tracks that were too long for release on 10-inch S D 78s. (Unlike Session, S D did not experiment with the 12-inch format.) The Cassino Simpson session, from 1942, is the second live session to see release on a S D 78 (and then just one side was used, which was held for release until the end of 1947).

Cassino Simpson (p).

Elgin Mental Hospital, Elgin, Illinois, May 17, 1942

| Tea for Two | Paramount CJS109, Chicago Piano 12-001 | ||

| It Don't Mean a Thing | Paramount CJS109, Chicago Piano 12-001 | ||

| Blues Variations | Paramount CJS109, Chicago Piano 12-001 | ||

| Moonglow | Paramount CJS109, Chicago Piano 12-001 | ||

| Song of the Wanderer | Paramount CJS109, Chicago Piano 12-001 | ||

| Little Joe | Paramount CJS109, Chicago Piano 12-001 | ||

| Lost in a Fog | Paramount CJS109, Chicago Piano 12-001 | ||

| Variations on Variations [Variations^] | Paramount CJS109, Chicago Piano 12-001^ | ||

| UP 102 DP | After You're Gone [sic] | S D Merry Christmas 1947* |

The Cassino Simpson outing was more of Steiner and Davis's more daring endeavors. They recorded Simpson while visiting him at the Elgin Mental Hospital, where the famed pianist was a patient. They'd became aware of his presence there in 1940, but were not able to record him then, and might very well not have been able to record him at all. In a reminiscence about his location recording trips with Hugh Davis, before World War II rationing set in, Steiner said:

In the old days — about the fall of '40, anyway we had gas, Davis and I with an evening for idle pleasure, low on dough, and by chance carrying our several hundred pounds of recording junk in the back, set out to locate TALENT. It seems we were at the moment definitely hyped by having 'discovered', at least for ourselves, within the preceding month or two Cass Simpson in Elgin, the Bert Bailey Six in Milwaukee and the unbelievably magnificent (in the Panassie idiom) Kenneth Morris, director of music at the colored First Church of Ascension. (The Jazz Session, No. 5, January-February 1945, p. 3)

(There is evidence from the Steiner Collection that they made location recordings at the church, though not for release on S D. We don't know what happened with the Bert Bailey Six.)

Swiss jazz researcher Johnny Simmen ("Cassino Simpson," Storyville no. 28, April-May 1970, pp. 123-127) noted that Steiner wrote him in 1940 about discovering Simpson at the mental hospital, remarking, however, that there was "no hope of getting him to record." Obviously somebody had talked to someone and something had changed by 1942. However, Simmen, like J. R. Simpson in his 1955 Jazz Journal article on Cassino Simpson, dated the recordings to 1944 and 1945.

The only track to be released on a 78 appeared on S D Merry Christmas 1947, a special gift record issued in a limited edition. The Merry Christmas 78 looks hastily put together, as "After You've Gone" is misrendered, and the recording date is given as 1944 (though that might have been a strategic decision, safely postdating S D's deal with the Union). In the trail-off shellac what we've written as DP is a monogram of a D with a P stuck in it; it stood for Dike-Polzin, a company in Pasadena, California that made masters and mothers for pressing companies like Bishop. On the flip side was a Red Nichols side of a radio broadcast transcription that Steiner picked up in Los Angeles (see session SD16 below). For a discography (by John Steiner himself) of the Merry Christmas releases, see the Matrix 21 (January 1959), p. 21, where gave the date for the Simpson side as May 17, 1942.

Steiner may have originally intended a different discmate for "After You've Gone." The January 1954 issue of the Record Changer (p. 24) offered at auction an unnumbered S D coupling of the Mel Henke Trio playing "Hindustan" and Cassino Simpson playing what was described as "After U Gone." We know of no actual S D releases by Mel Henke, a pianist then active in Chicago and Milwaukee who operated his own label for a brief period. In 1946 and 1947, Henke was signed to other companies—notably Vitacoustic, to which he was under contract in December 1947

The remaining sides would lie on the shelf until Steiner revived the Paramount label in 1949 and began issuing Paramount LPs in 1952. In fact, Paramount CJS 109 didn't appear till 1954. Chicago Piano 12-001 was released in the 1970s; Cassino Simpson was given the B side while the A side was taken up with 4 recordings of Kansas City Frank Melrose that Steiner got from the American Record Company and 2 from Paramount (well, sort of, where the Paramounts were concerned) and initially released in 1952 on Paramount CJS 103, a complicated entity to be described later on.

Steiner and Davis had developed an appreciation for Simpson from his work on several Paramount sides, notably the ones he made with singer/pianist Laura Rucker, who turned over the keyboard duties for the 1931 session (two of these sides were selected for reissue in the S D 100 series; see SDR3 and SDR4 below).

Pianist Cassino Wendell Simpson was born in either Chicago or Venice, Italy, on July 22, 1909. He recorded as early as 1923 with trumpeter Bernie Young and then worked with Arthur Simm's orchestra, which was subsequently led by Young. Simpson left the Young orchestra in 1930. For a time he worked with Erskine Tate. In 1929, Simpson made some valuable jazz recordings with Jabbo Smith and Ikey Robinson. During 1931-33, Simpson led his own bands in Chicago, followed by a stint accompanying Frankie "Half Pint" Jaxon.

In 1932 or thereabouts, Milt Hinton played in a band with Simpson at the Showboat. The front man was trumpeter Jabbo Smith; John Thomas was the trombonist; Scoops Carry, Jerome "Don" Pasquall, and Scoville Brown made up the reed section; Ted Tinsley was the rhythm guitarist; and Floyd Campbell (later replaced by Richard Barnet) was in the drum chair.

In his memoirs, Hinton recalled Simpson this way:

In addition to playing the piano, Cass Simpson wrote most of the arrangements. He was a brilliant musician—one of the guys from that era that I'll never forget. He was light complected and his face was scarred from small pox. He always smoked a cigar when he played and he'd let the ashes fall all around him. After he'd smoked it down to a little stub he'd put the whole thing in his mouth, chew on it for fifteen or twenty minutes, then spit out whatever was left. By the end of the night the bandstand was filthy and also smelled pretty foul.

We played what would probably be called New Orleans-style. Cass actually wrote out the parts so the reeds and brass could harmonize during the solos. He also composed new tunes, and for some reason always named them after soul food like neckbones and rice, mustard greens and pig tails, cabbage and black eyes.

Cass was also an unbelievable piano player. He had Art Tatum's depth and Oscar Peteron's fire. I've never really heard anybody else play that way. But like a lot of geniuses he had some serious mental problems and I think all of us knew it, even back then. (The Bass Line, p. 50)

After the club owners fired Jabbo Smith, who often missed the entire first set, and sometimes skipped out before the night's work was over, Simpson took over as leader. The band continued for a little while, doing freelance jobs and working a couple of nights per week at the Regal Theater.

In 1935, the mental problems came to the fore when Simpson tried to kill "Half-Pint" Jaxon. Cassino Simpson was admitted to the Elgin Mental Hospital. In the hospital he played drum in the marching band and piano and vibes in the dance band. As might be expected, the S D recordings were the only ones he made in the asylum. He died there on March 27, 1952.

Simpson sources: John Chilton, Who’s Who of Jazz: Storyville to Swing Street (Philadelphia: Chilton Book Company, 1972): 338; Milt Hinton, The Bass Line: 50; Tom Lord, The Jazz Discography, Volume 20 (West Vancouver, B.C.: Lord’s Music, 1998): S729.

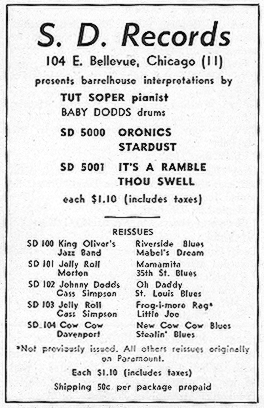

Newly recorded material on S D began to appear on a 5000 series, on which Steiner put out releases by pianist Tut Soper and vibist Red Norvo with the Stuff Smith Quartets. S D 5000 and 5001, both by Tut Soper, were on sale by mid-May 1944. An advertisement for S D Records in Down Beat (May 15, 1944) lists 5000 and 5001 along with 100 through 104 (see below for the 100 reissue series).

The August 15, 1944 issue of Down Beat announced that 5000 and 5001 could also be purchased on wire, at a time when this predecessor to tape recording was not yet seen as a retail medium. S D was a true innovator in this realm. According to Bjöaut;rn Englund in his article "Early Pre-Recorded Tapes (1955-1957), "In the 1940s the Webcor wire-recorder achieved some popularity and John Steiner in Chicago issued a few titles from his Steiner-Davis label as prerecorded wires. This is the only label known to have done so" (Names & Numbers 36, January 2006, p. 38). Aristocrat briefly showed an interest in wire recording, though not for release. Other record companies didn't get into the action until 1950 or later, when some began offering prerecorded tapes.

5000 and 5001 were listed again in S D's advertisement in The Jazz Record for November 1944.

S D 5002 and 5003 were also planned in 1944. But so far as we can determine, they didn't make it into circulation before the fall of that year, when Steiner quit trying to press S D records. After which, they spent an amazingly long time in limbo... we have no evidence that they were released before 1949. But more about all of that below.

The labels on 5000 and 5001 listed the company’s address, but misspelled Bellevue as "Bellvue." As he would do on all subsequent sessions, Steiner assigned master numbers according to the date of the recording and the take.

Oro "Tut" Soper (p, vcl -1); Warren "Baby" Dodds (d, vcl -2).

Jack Gardner's apartment, Chicago, January 31, 1944

| 13144-1; CRC 9132A 13144-1 |

Oronics [No. 1] (Soper) | S D 5000 A | |

| 13144-2 | Butter & Egg Man (#1) -1, 2 | unissued | |

| 13144-3 | Butter & Egg Man (#2) -1, 2 | — | |

| 13144-4 | That's a Plenty | Baby Dodds 2 | |

| 13144-5 | Oronics No. 2 (Soper) | unissued | |

| SD 13144-6A ; CRC 9135 A 13144-6 A |

It's a Ramble (Soper) | S D 5001 A | |

| 13144-7 | Right Kind of Love -1 | unissued | |

| 13144-8;

CRC 9133 A

13144-8; DP 7 |

Thou Swell (Rodgers-Hart) | S D 5001 B | |

| 13144-9 | Keeping Myself for You | unissued | |

| 13144-10 ; CRC 9134 A13144-10 DP 7 | Stardust Stomp (Carmichael) | S D 5000 B | |

| 13144-11 | Oronics No. 3 (Soper) | unissued | |

| 13144-12 | Tea For Two (drum novelty) | Baby Dodds 2, Dan [Jap] VC-4013, VC-7015 |

Tom Lord in a note below his listing said that there may have been a release on a 16-inch disk that contains this entire session. (Most likely, he is just referring to the session master; 16-inch acetates and transcription disks were common at this time.) Lord, like some other discographers, refers to all S D releases as "Steiner-Davis." But none of the labels actually read "Steiner-Davis." In articles about his company and in advertisements, John Steiner followed the punctuation practices of his day and wrote "S. D.," but there are no periods on the labels. Nor was there ever a hyphen between the S and the D.

S D 5000 and 5001 were apparently pressed in two distinct runs. Some copies (including S D 5000 and 5001 in Konrad Nowakowski's collection) show the matrix numbers shown at the top, with CRC 9100 series numbers in the trailoff area. CRC was Chicago Recording Company, and by implication the pressings were done at a plant in the Chicago area.

Other copies (such as those in Tom Kelly's collection) leave off the CRC numbers and show a monogram (a D with a P stuck in it) and a number 7 in the runoff on one side. The same DP monogram can be seen on some Session releases from this period. The Bishop pressings date from 1947 (S D 5000 and 5001 were not in Steiner's initial order) through 1950 (Steiner got his masters back from Bishop in September of that year). During that period, Steiner often ordered pressings of multiple records in very small quantities each.

We now know, from the correspondence with The Bishop Presses that John Steiner largely preserved (now in Box 26 Folder 22 in the John Steiner collection af the University of Chicago), that DP stood for Dike-Polzin Co., Record Processing, which was located at 221 South Arroyo Parkway in Pasadena, California. Dike-Polzin, which later changed its name to Deeco, did masters and mothers for many of the records that Bishop pressed in South Pasadena.

S D 5000 and 5001 remained in Steiner's catalog until at least 1952, as they are advertised in a booklet that was included with his first Paramount10-inch LP release, Paramount CJS101.

Pianist Tut Soper was born Oro M. Soper on April 9, 1910. In the early 1920s, Soper made a record on OKeh with a group of kids, all 13 and under, called The Five Baby Shieks. Besides Soper on piano, they included Art Elefson on drums, Howard Snyder on sax, and Elmer Fearn on violin. By the late 1920s he was a regular in Chicago clubs, despite being underaged, and performing with Bunny Berrigan, Wingy Mannone, Boyd Brown, and Floyd Town. After years of playing in bands, in the late 1930s Soper went solo, introduced vocals to his repertoire, and played in such clubs as the legendary Three Deuces (222 North State).

By the war years, Soper could be found in the Randolph Street nightclub district. He was playing around the corner from Randolph Street at the Capitol Lounge on State when his S D recordings were made. Steiner and Davis teamed Soper up with Dodds in pianist Jack Gardner’s apartment for the session. Gardner owned a particularly fine piano, which is why the session was held in his place, at 102 East Bellevue, a basement apartment located in the same complex as John Steiner's. Jazz fans tend to revel in improvisation, and Down Beat columnist George Hoefer loved the idea at how "impromptu" the recording was, as Soper and Dodds had never met before, and had to feel each other out in the recording process.

Lord lists "Oronics No. 3" as being released on S D 5000, but Hoefer in his "Hot Box" column of 15 June 1944 lists the title as simply "Oronics," and gives the master number as 13144-1. He goes into detail how the "first test" of the number turned out to be the best, and ended up being used for release. We'll go with Hoefer on this; besides, the matrix numbers on S D 5000 back him up.

Down Beat reviewer John Lucas—who tended to give favorable reviews to his collector colleagues’ product—cited these releases as "some of the finest jazz piano waxed in many years." He raved about each one of the songs, and concluded, "The rip-rattling drum accompaniment provided by the one and only Baby Dodds simply could not be touched by anyone else. If Soper is super, Dodds is at once devastating, dynamic, and droll!"

In a lengthy review published in the October 1944 issue of The Jazz Record, George Avakian gave effusive praise to S D 5000 and 5001. "Picture Earl Hines in the full flower of his wildest period, playing as though it were his last chance to explode through with vital ideas of earth-shaking consequence. This is Tut Soper; an exciting, intensely live pianist whose work doesn't merely "send" you the way many agitated instrumentalists can—it reaches out, grabs you by the throat, and shakes and chokes hell out of you" (p. 3). Avakian contrasted Soper's genuineness and avoidance of clichés with the mannerisms of "the present-day frantic clique," into which he went so far as to lump "such hopeless musicians as Lionel Hampton, Art Tatum, Roy Eldridge, Dizzy Gillespie, and a whole string of trumpet players, electric guitar virtuosos, and Hazel Scotts" (p. 3). Out of the four, Avakian declared that "[t]he originals—Oronics and It's a Ramble—are my pet sides, displaying Tut's talents in two tempos and two moods, both nonetheless full of his overall excitement. The first is sheer panic, but good; the Ramble is reflective and rather interestingly developed from the melodic view. The others are Soper franticizations of Thou Swell and Star Dust, and the tunes improve under his manhandling." (p. 3.) Of Dodds' contributions, Avakian complained (p. 11) that the drummer "loses much of his subtlety" on Oronics, but praised him for his rapport with Soper elswhere on the session.

John Chilton described Soper as one of the leading pianists in Chicago, and credited him with working with Bud Freeman, Wild Bill Davison, Boyce Brown, Bud Jacobson, and Eddie Wiggins, among others. In the early 1950s, Soper worked in California with Muggsy Spanier and Marty Marsala. He toured with Eddie Condon in 1960.

Soper in his later years worked mostly as an insurance salesman for the Chicago Motor Club. He died in March 1987. His obit described him as a former jazz pianist, who had played for 50 years in "some of Chicago’s most famous jazz clubs and with the bands of Gene Krupa and Bud Freeman."

Soper sources: M/Sgt. George Avakian, "Records—Old and New," The Jazz Record, October 1944, pp. 3, 11; George Hoefer Jr., "The Hot Box," Down Beat, 15 June 1944; [John Lucas] "Diggin’ The Discs," Down Beat, 15 July 1944, p. 8; Catherine Jacobson, "Oro ‘Tut’ Soper," Jazz Vol. 1, No. 10 (December 1943): 8-9; "Oro Soper" [Obit], Chicago Tribune, March 24, 1987; Tom Lord, The Jazz Discography, Volume 21 (West Vancouver, B.C.: Lord’s Music, 1999): S1057.

John Steiner’s North side apartment at 104 East Bellevue was the location for the next S D session, which teamed up two legends of jazz—vibist Red Norvo and violinist Stuff Smith—accompanied by Remo Palmieri on guitar and Clyde Lombardi on bass.

Anthony Barnett has recently revised his discographical listing for this session, and we are following him here.

Stuff Smith (vln); Kenneth Norville [Red Norvo] (xyl); Remo Palmieri (eg); Clyde Lombardi (b).

John Steiner's home, Chicago, April 5, 1944

| unknown master number 4544-0B as released |

Rehearsal [Red’s Stuff (Norvo-Smith)] | S D 5002 A (part) | |

| 4544-00 4544-0B as released |

Rehearsal [Red’s Stuff (Norvo-Smith)] | S D 5002 A (part) | |

| 4544-1 | Red’s Stuff (Norvo-Smith) | unissued | |

| 4544-2 | Red’s Stuff (Norvo-Smith) | unissued | |

| 4544-3 | Red’s Stuff (Norvo-Smith) | unissued | |

| 4544-4a | Red’s Stuff (Norvo-Smith) [false start] | unissued | |

| 4544-4b | Red’s Stuff (Norvo-Smith) | unissued | |

| 4544-5B | Red’s Stuff (Norvo-Smith) | S D 5002 B | |

| 4544-6 | Confessin’ (Neiburg-Dougherty-Reynolds) | unissued | |

| 4544-7B | Confessin’ (Neiburg-Dougherty-Reynolds) | S D 5003 A | |

| 4544-8 | Confessin’ (Neiburg-Dougherty-Reynolds) | unissued | |

| 4544-9 | Confessin’ (Neiburg-Dougherty-Reynolds) | unissued | |

| 4544-10 | A Fawn Jumped at Dawn (Palmieri) | unissued | |

| 4544-11B | A Fawn (Palmieri) | S D 5003 B | |

| 4544-12 | Blue Hugh’s Hue | unissued |

We drew our information on the session from Anthony Barnett's book Desert Sands, the definitive bio-discography of Stuff Smith. (See p. 111 for the discographical entry.) Although Tom Lord used Barnett as a source, several errors crept into the listing for this session in Lord's Jazz Discography. Recently, Anthony Barnett discovered that the Rehearsal, as released on S D 5002 A, is actually an edited composite of 4544-00 and another lacquer that apparently has been lost. Meanwhile, 4544-4b was not used for the released "Rehearsal," as previously thought; it is still unissued. Courtesy of Anthony Barnett, we have updated this session listing with the latest information available.

As released on S D 5002 A, the "Rehearsal" (of "Red's Stuff") consists of edited material from two masters. The first half of the released side is the extant master 4544-00, with a minute or so of talk and fragmented passages edited out. The second half of the released side (music, no talk) is from a master apparently now lost (maybe it was 4544-0); we of course don't know whether all of the lost master was used or not.

On the labels to S D 5002 and 5003, all four musicians are listed, but Red Norvo appears under his real name, as "K. Norville." The date is given on the label as April 4, 1944, but the matrix numbers indicate April 5, which is confirmed by the session sheet.

The 78 lists "Red’s Stuff" on the label while the recording sheet says "Red Stuff." On Side A of S D 5002, Anthony Barnett indicates that track 4544-00 (possibly edited) is followed by material from a lacquer that may be lost. A cassette copy of the session made by John Steiner gave the last track the title "Blue Hugh's Hue"; on the session sheet, the piece was untitled.

A copy of S D 5002 in the collection of Konrad Nowakowski shows SD 4544-0B on the A side, and carries the Dike-Polzin monograph in the runoff area. Copies with the DP were pressed by Bishop in South Pasadena, California. The B side of Nowakowki's copy shows DP and B9 in the trailoff area. A close inspection of S D 5003 is also warranted.

As noted by Barnett, "Red’s Stuff" would be recorded for Keynote in July 1944 (on a session that included Teddy Wilson and Slam Stewart) as "Blues à la Red." Norvo subsequently recorded "Blue Hugh's Hue" for World Transcriptions (in May or June 1944) and for V Disc (in May). Both of these later recordings used the title "Red Dust" (credited to Fletcher Henderson).

For another photo taken at the session, showing the musicians listening to a playback, see the AB Fable Archives site.

The release dates for S D 5002 and 5003 continue to puzzle us. The release numbers and the appearance of the labels indicate a planned release in 1944. S D 5002 and 5003 were announced by Leonard Feather in the 1945 Esquire Jazz Guide (p. 123, in a volume that was actually published in December 1944).

However, a test pressing of S D 5003 shows the 8 South Dearborn address, which is from 1947 or 1948. And Charles Delaunay's Hot Discography from 1948 lists S D 5000 and 5001—but not 5002 and 5003. In the Steiner-Bishop correspondence, the first request for pressings of 5002 and 5003 was sent on March 4, 1949. Steiner was billed on March 31, 1949 for 227 copies of S D 5002, probably (the invoice repeats 5003 for two different records), and 229 copies of S D 5003. These were good-sized orders for Steiner, though not necessarily the biggest he would make for these two 78s. The first known advertisement for 5002 and 5003 appeared in the Record Changer for July/August 1950. (And a list of titles for sale included in a booklet with Paramount LP CJS101, which was released in 1952, mentions "Red Norvo and Stuff Smith Quartet" but mislists the items as S D 5000 and 5001...) Since we haven't found an earlier review or ad for these 78s, we have to go with April 1949 as the release date, but we find the length of the delay intensely puzzling. Were a few demo copies circulated in 1944, followed by a commercially serious pressing run in 1949? Could there have been some legal tie-up?

Red Norvo was born Kenneth Norville on March 31, 1908, in Beardstown, Illinois. He built his reputation playing the xylophone and marimba, but also played piano. He began his career touring with a marimba band, the Collegians, in 1925. His first session under his own name was in 1929 for Brunswick Records, but it went unreleased. His next recording opportunity came in 1933. Meanwhile, he had been working with the Paul Whiteman Orchestra in 1931, and there met Mildred Bailey, to whom he would be married for 12 years.

In 1933 Norvo got a band together, Red Norvo and His Swing Septet, and began recording for Columbia. Thereafter he was rarely out of the recording booth. His last Columbia recording was done in 1942. From 1935 to 1944 Norvo led bands from small combos to large orchestras. In October 1943 he recorded V-Discs for broadcast to the armed services. By this time he had switched from xylophone to vibraphone.

The April 1944 S D session was something of a coup for Steiner and Davis. They were of course recording him for what he represented in the past. Although Steiner would eventually issue a live broadcast featuring Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, it is most unlikely that he and Hugh Davis were anticipating anything like Red's famous 1945 session for Comet that included Bird and Diz.

In 1944, Norvo disbanded his sextet and joined the Benny Goodman band, and the following year saw him in Woody Herman’s band. In 1947, moved to Santa Monica, California and returned to leading his own combo. His 1950-1951 trio with Tal Farlow on electric guitar and Charles Mingus on bass was one of the leading "cool jazz" ensembles. During the 1960s, he had a long residency at the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas. Norvo had to retire from playing after suffering a stroke in 1986; he died in Santa Monica, California, on April 6, 1999.

Norvo sources: John Chilton, Who’s Who of Jazz: Storyville to Swing Street (Philadelphia: Chilton Book Company, 1972): 277-78; Barry Kernfeld, "Red Norvo," The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz (London: Macmillan, 2002, 2nd edition, Vol. 3, pp. 165-167); "Red Norvo, 91, Who Introduced Xylophone to Jazz," Chicago Tribune, 8 April 1999; Tom Lord, The Jazz Discography, Volume 16 (West Vancouver, B.C.: Lord’s Music, 1997): N350.

We will be adding a capsule biography of Stuff Smith one of these days.

Smith sources: Anthony Barnett, Desert Sands: The Recordings and Performances of Stuff Smith. (Lewes, East Sussex: Allardyce, Barnett, 1995).

Probably intended at one time for release in the 5000 series was a session by pianist Chet Roble and his group. All we know about this one is that Steiner cut it in the summer of 1944; an item in the August 15 issue of Down Beat signaled that the group had been recorded "for S D." But no releases ever emerged (even years later, when Steiner was putting out LPs on Paramount) and it is doubtful whether any tracks are still extant. Roble also recorded, with his trio of Boyce Brown on alto sax and Sammy Aron on bass, in July 1946 for Morton Sultan's Detroit-based label. But the sides were never released. In the 1950s, Roble made a single for Topper (1952) and an LP for Argo (1958), more pop-oriented efforts from a period in which he was working piano bars.

For releases planned after he stopped trying to press S D's in the fall of 1944, Steinter dropped a zero out of the 5000 series numbers and hopped from 5003 to 504. Of course, the earliest session listed here (Punch Miller, 1941) ended up as the last in the series, on 509 and 510.

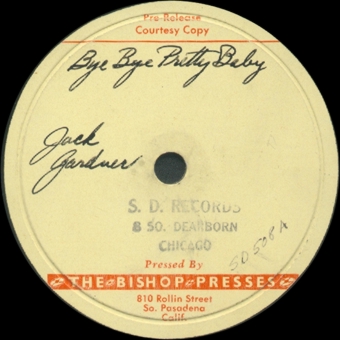

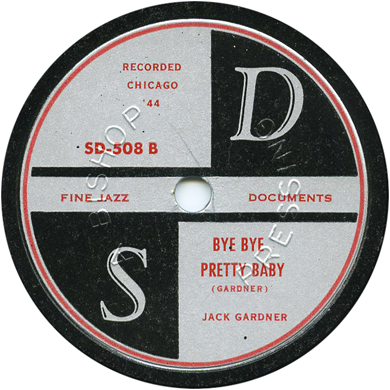

While the 500 series releases got going in January 1947 (Steiner made his first pressing order from Bishop on December 16, 1956, taking delivery early the next month), the sessions they were drawn from took place in 1941, 1944, and 1946. In January 1944, Steiner and Davis waxed their friend, pianist Jack Gardner, accompanied by Baby Dodds on drums. Their Gardner 78 paired one number from the January session and another from a session in June 1944. We should note that both the 5000 and the 500 series featured a label design in which the S was in the lower left quadrant and the D in the upper right, not connected by any hyphen. This is why refer to the label as S D, not S-D.

We know of releases on 504, 505, 506, 507, 508, 509 and 510.

Jack Gardner (p); Warren "Baby" Dodds (d).

503 West Aldine, Chicago, January 31, 1944

| SD1314461B DP | Doll Rag | S D 508 A |

Jack Gardner (p).

503 West Aldine, Chicago, June 30, 1944

| SD63044-9B DP | Bye Bye Pretty Baby (Gardner) | S D 508 B | |

| Rolling around in Roses | unissued |

The copy of S D 508 in Tom Kelly's collection is stamped "A Bishop Pressing" on the B side, under the label, in a fashion that is familiar from Bishop's 1946 and 1947 pressings of Session 78s. A copy in Konrad Nowakowski's collection shows 61B in the runoff area (we'd previously construed this as GIB); both sides carry the Dike-Polzin monograph in the runoff area. A test pressing of 508, in Volker Dorendorf's collection, was also done at Bishop, a pressing plant located in South Pasadena, California, where it began operations in April 1946. The test pressing gives "Paper Doll" as the title of "Doll Rag."

S D 507 and 508 were delayed for more than a year past 504 through 506. 504 through 506 were ready for release in January 1947. 507 and 508 were released in May 1948. On May 4, The Bishop Presses billed Steiner for 116 copies of S D 507 and 198 of S D 508, 20 cents a pressing. Both were advertised in the Record Changer for June 1948—but not mentioned in the company's ads in the same magazine that appeared in the July, August, and December 1947 issues.

Jack Gardner was born Francis Henry Gardner, August 14, 1903, in Joliet, Illinois. At the age of eight he began playing piano, after his family had moved to Denver. He moved to Chicago 1923 to play in Spike Hamilton’s Band. Jack Gardner first recorded in 1924 for OKeh, leading his own group. He did another session for the label the following year, and led his own touring band in the late 1920s. He also recorded with Wingy Manone (1928) and Jimmy McPartland (1936). In 1937 Gardner moved to New York. During 1939-1940 Gardner served as pianist for the Harry James Orchestra. Returning to Chicago, he led a trio at the Silver Palm (1117 West Wilson) for a while, and developed a friendship with John Steiner, out of which the S D session arose. Gardner subsequently moved to Texas. He died in Dallas on November 26, 1957.

Gardner sources: John Chilton, Who’s Who of Jazz: Storyville to Swing Street (Philadelphia: Chilton Book Company, 1972): 129; Tom Lord, The Jazz Discography, Volume 7 (West Vancouver, B.C.: Lord’s Music, 1993): G47-48.

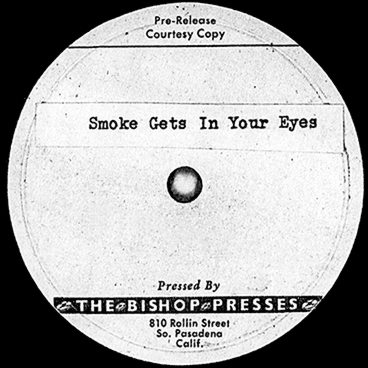

The session of June 30, 1944, also included 3 titles laid down by an unusual trio that consisted of Gardner at the piano, Red Nichols on cornet, and Vic Engle in the drum chair. The story of the June 30th outing—a truly impromptu affair—was told in an article on Red Nichols in Record Research (combined issue 96-97, p. 10). Not long after he and his wife bought a house in Los Angeles, Nichols was en route to his new home when he passed through Chicago. "Red was staying at the Sherman Hotel and met Vic Engle at the Croydon Hotel by chance. They phoned John Steiner to ask 'what's happening?' On a quick impulse they set up a recording date. They used Jack Gardner because they could get his piano and room for the job—it took place at 503 W. Aldine St. on June 30. It was a tentative deal, but John liked the results immediately and paid off. That trio never worked before or after the two hours before Red's plane left for the coast."

Red Nichols (cnt); Jack Gardner (p); Victor Engle (d).

503 West Aldine, Chicago, June 30, 1944

| 63044-1 | Cheerful Little Earful | test pressing | |

| 63044-1B | Cheerful Little Earfull [sic] | test pressing | |

| 63044-3B | Cheerful Little Earful | S D 507 A | |

| 63044-4B | I’ve Got a Woman [She’s Funny That Way] | S D 507 B, VJC VJC1009 (CD) | |

| 63044-5B | Smoke Gets in Your Eyes | test pressing |

The copy of S D 507 in Tom Kelly's collection was pressed by Bishop, an outfit in South Pasadena, California whose major customers were Jump, Session, and some other small indies with a jazz orientation. S D 507 dates from May 1948; on May 4, Steiner was billed for 116 copies of S D 507. A test pressing from this session—we are not sure about the coupling—was mentioned in a December 1947 article.

Lord claims that in all only 300 copies of S D 507 were pressed—this is according to information he had received from collector Jack Hester. We don't have documentation for later pressing runs on 507, but from the first run, the total seems about right. The VJC CD was titled Trumpet Royalty; the remainder of its cuts were by other artists.

One 78-rpm test pressing, made by Bishop, of 63044-1B backed by 63044-5B is now in the collection of Warren Hicks. At least one other test pressing is known to be extant; it has 63044-1 on one side.

Cornetist and bandleader Red Nichols was born Earnest Loring Nichols in Ogden, Utah, on May 8, 1905. He learned cornet under his father, a college music professor and leader of his family brass band. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s he was one of the most prolifically recorded of the white jazzmen, leading bands that enjoyed great popularity. His most significant recording legacy was the Brunswick recordings he made in the late 1920s under the name Red Nichols and His Five Pennies, a recording ensemble of varying size and lineup that included such musicians as Jimmy Dorsey, Eddie Lang, Miff Mole, Joe Venuti, Jack Teagarden, and Benny Goodman. During much of the 1940s and early 1950s, Nichols played long residencies in West Coast venues, notably El Morocco Club in Los Angeles and Club Hangover in San Francisco.

But Nichols emerged as a legend. In 1959 he played for the soundtrack of the movie, The Five Pennies, which in the typical Hollywood way—it starred Danny Kaye as Red Nichols—was loosely based on his life. Nichols found new popularity, and toured Europe in 1960 and 1964. He died in Las Vegas, on June 28, 1965.

Nichols sources: John Chilton, Who’s Who of Jazz: Storyville to Swing Street (Philadelphia: Chilton Book Company, 1972): 275-76; Tom Lord, The Jazz Discography, Volume 16 (West Vancouver, B.C.: Lord’s Music, 1997): N243-258.

A little while after the Red Nichols session, S D went into temporary hiatus. As Steiner would later explain, "In the fall of 1944 with record pressing at its highest output, and, as a result of shortages, lowest quality, since the turn of the century, S. D. Records suspended activity to await the availability of a prideful type of disc" ("Records to Burn," The Jazz Record, September 1946, p. 5). The company had released 2 78s in its 5000 series and 5 in its 100 reissue series by the middle of May 1944, though we are pretty sure there was some additional production of demo copies.

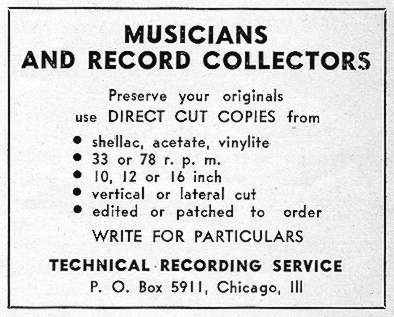

In February 1945, it was announced that Steiner had bought out Hugh Davis’s share in S D. Davis apparently had lost interest in the partnership. As George Hoefer reported, "Davis has other record activities not conducive to his continuing with S D." Steiner later stated that "Hugh Davis opened his Technical Recording Service, offering fine acetate copies of out-of-print records, non-commercial transcriptions, private recordings and off-the-air shots. It was expedient then for me to purchase his interest in S. D. and await the New Day" when the company could get more records pressed with reasonable quality ("Records to Burn," p. 5).

A brief item on Technical Recording Service appeared in Down Beat on May 21, 1947. It promised "all types of services... including direct-cut copying of valuable collector's titems, copies by re-recording, editing and patching of copies. The latter allows for copying certain choruses only and patching portions of one or more records together on a single plate. Concert 'air shots' are also available."

Hugh Davis would die way too soon, in 1948. He was survived by his wife Nina and a son, Bill. Steiner would later marry Nina.

Meanwhile, the lull in S D's operations dragged on. Steiner would announce impending releases, then they would fail to appear. In George Hoefer, Jr.'s column of July 1, 1945, Steiner reported that he would be releasing the results from a live recording he and Davis had made at the H & T Tavern in 1941, featuring trumpeter Punch Miller and drummer Clifford "Snags" Jones. Granted, all that he promised was that the sides would appear "sometime in the future." We aren't too sure when. The John Steiner Collection, now at the University of Chicago Library, has finished, printed labels for two Punch Miller singles, S D 509 and 510. But we have not seen the actual records. Any that Steiner ordered must have been pressed by Bishop between 1948 and 1950, in what he called "experimental lots": 20 or 25 of each. Four of the six 1941 sides showed up in 1952 as on side of a 10-inch LP, CJS 102 on Steiner’s revived Paramount imprint.

Steiner had become preoccupied with the extensive work he was doing at the Uptown Playhouse Theater (1225 North LaSalle at Goethe). Initially he was called in to fix the group's recording equipment:

The Uptown Players, directed by James Bradley-Griffin, a flamboyant theater character of the wild Woolley-Barrymore genre, had purchased a marvelous building for their activities including work rooms, a recording studio, class rooms, and a 500-seat theater. Within the Players' first few months' occupancy, as a result of inexpert handling, the recording mechanism, radios and phonographs had gone out of adjustment. The group was thoroughly discouraged with their own talent at mechanics and electronics and were casting about for an operator. Davis and I edged in and salvaged a good recording unit and rebuilt the acoustics of their studio.

At a moment when the job was finished and Griffin beamed appreciation (his glow possibly heightened by a quart of ale) I arrived at an agreement with him for my services as a recording operator and janitor of electronics in exchange for a basement room in which to store [a couple of large record collections], as well as a large stock of my own and a residue of S. D. left-overs which had begun to bulge the original S. D. Studios at 104 East Bellevue. The arrangement suited both of us ideally and after a few months I was given several large rooms in the theater to refurbish as an apartment for myself in order that the Players could offer 24-hour recording service. ("Records to Burn," p. 5)

With 5 pianos in playable condition, several record players, radios, and even portable recording equipment available, the theater evolved into a major hangout for traditional jazz musicians and fans. In the July-August 1945 issue of the Record Changer, Steiner actually gave 1225 North Lasalle as the new address for S D.

As though all of this informal activity wasn't enough, Steiner branched out into public concerts. He organized a series of "jazz musicales" for the first and third Sunday afternoons of each month during July and August 1945 at the Uptown Playhouse Theater . His first session featured Bud Jacobson’s Jungle Kings. While Down Beat columnist Don C. Haynes was unimpressed by the group as a whole, he lauded the work of pianist Tut Soper and guitarist Jack Goss. In August, Steiner sponsored the Jimmy Noone Memorial Concert at the Uptown Playhouse, which featured a band consisting of Darnell Howard (clarinet), Boyce Brown (alto sax), Baby Dodds (drums), Gideon Honoré (piano), Jack Goss (guitar), Tut Soper (second piano), and Pat Pattison (bass). In addition, Steiner was doing a bunch of recording at the Playhouse.

Bud Jacobson (cl -1, p -2, ts -3); Volly De Faut (cl -4, d -5); Darnell Howard (cl -6); Dave North (p -7); Mel Grant (p -8); Jack Goss (g -9); Frank Lehman (b -10).

Uptown Playhouse Theater, Chicago, June 1945

| Cherry -2, 4, 9, 10 | unissued | ||

| Fast Blues -1, 5, 7 | — | ||

| High Society -3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 10 | — |

These three entries are taken from Lord's Jazz Discography. The first two are dated June 1945 while the third is dated 1945 with no location noted. All are attributed to "Steiner Davis." Are the masters still extant?

Bud Jacobson (ts); Johnny Mendel (tp); Warren Smith (tb); Volly De Faut (cl); Tut Soper (p); Jack Goss (g); Jim Lannigan (b); Claude Humphries (d).

Uptown Playhouse Theater, Chicago, July 1, 1945

| NOS601 | Digga Digga Do (Part 1) | While Label 17040 | |

| NOS601 | Digga Digga Do (Part 2) | White Label 17040 |

This item apparently survived. All information from Lord's Jazz Discography; has anyone seen the White Label release?

Lord lists three other unissued sessions for Bud Jacobson, dated March 1944, 1945, and 1946, but they are either credited to the Signature label, or merely cited as unissued without a label affiliation, so we have not them here.

The concerts ended when Steiner found himself in a spot of trouble with the Musicians Union. Reported Jazz Session editor John T. Schenck, "John Steiner, the person responsible for some very fine jam sessions in Chicago, ruined his chance for putting on future sessions, and possibly chances for others to stage jam sessions, by trying to pull a ‘fast one’ on the musician’s union by using a mixed band, avoiding to pay leader and stand-in money, and so on. ‘Know-it-all’ Steiner’s blunder will make it twice as difficult for the next person interested in staging a hot jazz concert or jam session." This kind of nastiness, unfortunately, was typical of Schenck, and Steiner never contributed another word to Jazz Session. Note the comment on the "mixed band." Steiner's trouble was with Local 10, the segregated White local of the Musicians Union. But Local 208, which had its own turf to guard, wasn't the most supportive of racially mixed bands at the time.

Steiner's own account is worth contrasting with Schenk's:

On Sunday afternoons in the summer of 1945 we held jam sessions in the theater, attracting with eight and ten-men bands capacity houses which allowed us to pay the men well over scale for their participation. But to pay beyond agreement proved inexpedient generosity, for the Petrillo hoods concluded that we must be making millions and thereupon assessed us $120.00 for the so-called standby charge, an infamous fee set aside for Union electioneering "benefits." Another so-called ruling which the Petrillo boys invoked included an assessment of 10% of the price of the band for using Tony Parenti, who carried only a traveling card, not local membership. We simply went broke; Union greed snuffed us out before the summer was out. ("Records to Burn," p. 6)

The only profit from the sessions was $19.90 out of the soft drink concession. Steiner did note that after he discontinued his sessions other trad enthusiasts formed the Chicago Hot Club, which was able to make a better deal with the Musicans Union.

After hotfooting it out of concert promotion, Steiner launched Jazz Record Seminars, which met every two weeks during the winter of 1945-1946. In 2 hour sessions, 20 or 30 records were played, with commentary from a panel of 3 or 4 experts. Musicians as well as record collectors attended regularly.

On top of the scheduled activities, informal sessions were going on just about constantly. One "jamboree" brought out no less than 27 of the local "hot boys," who according to Steiner produced 45 minutes of recordings. On that occasion, trumpeter Lee Collins, alto saxophonist Boyce Brown, clarinetists Darnell Howard and Volly DeFaut, no fewer than five pianists (Gideon Honoré, Tut Soper, Jack Gardner, Mel Henke, and Chet Roble), and drummer Jim Barnes were among the contributors.

Sources used: George Hoefer Jr., "The Hot Box," Down Beat, 15 February 1945, p. 11; George Hoefer Jr., "The Hot Box," Down Beat, 1 July 1945, p. 11; Don C. Haynes, "Jazz Struggles for Survival in Chicago," Down Beat, 15 July 1945, p. 4; George Hoefer Jr., "The Hot Box," Down Beat, 15 August 1945, p. 11; [John T. Schenck], "Steiner Sessions Fold Up," Jam Session 9 (September-October 1945): 26; John Steiner, "Records to Burn," The Jazz Record, September 1946, pp. 5, 6, 17.

While Steiner was recording regularly at the Playhouse, he must have intended the next session for release on S D, because he got George Hoefer to announce it in print.

Bert Patrick (as); Red Norvo (p); Jack Goss (g); Josh Billings (suitcase); Jim Hall (d).

Uptown Playhouse Theater, Chicago, January 1946

| Confessin’ | unissued | |

| Exactly like You | — | |

| I Talk about the Weather | — |

George Hoefer, in his February 11, 1946 "Hot Box" column, reported these titles in his rundown of "recent waxings." Apparently Steiner never released the titles; Lord cite them as unissued. Lord indicates that Norvo was playing vibes, but Hoefer lists him on piano. This grouping of musicians arose out of concerts Steiner was presenting at the Uptown Playhouse Theater. During intermissions at the Jimmie Noone Memorial Concert and the Baby Dodds Riverboat Band concert, Steiner featured performances by a revived vaudeville act, named the Mound City Blue Blowers after the legendary groups led by Red McKenzie. Steiner's reincarnated Blowers consisted of Frank "Josh" Billings playing a suitcase with whiskbrooms, Tut Soper on piano, and Jack Goss on guitar. According to Steiner, the same trio appeared on many informal sessions at the Uptown Playhouse, playing from 10 or 11 pm to daybreak.

It's hard for us to trace Bert Patrick's movements, because he rarely worked as a leader. On March 15, 1945, he filed an "indefinite" contract with Local 208 for a gig at The Irish Village, followed up by another indefinite contract on June 7. In November 1946 Bert Patrick was playing in Hillard Brown’s six-piece band at Joe’s Deluxe Club.

In 1954, Bert Patrick, now playing tenor sax, was in the studio band on several vocal sessions for a new small label called Drexel. The company's first session featured a doowop group, the Gems, singing "Talk about the Weather," which, in turn, was credited to Caldwell and Patrick (Les Caldwell was one of the label's owners). Bert Patrick appears to have been involved with Drexel for about a year; in 1955, he was replaced on the company's sessions by Johnny Houser. His last composer credit on Drexel was to a song titled "Atlantic Boardwalk," which was sung by Dave Turner.

Bert Patrick and Soper/Goss/Billings sources: George Hoefer Jr., "The Hot Box," Down Beat, 11 February 1946, p. 11; John Steiner, "Records to Burn," The Jazz Record, September 1946, pp. 5, 6, 17.

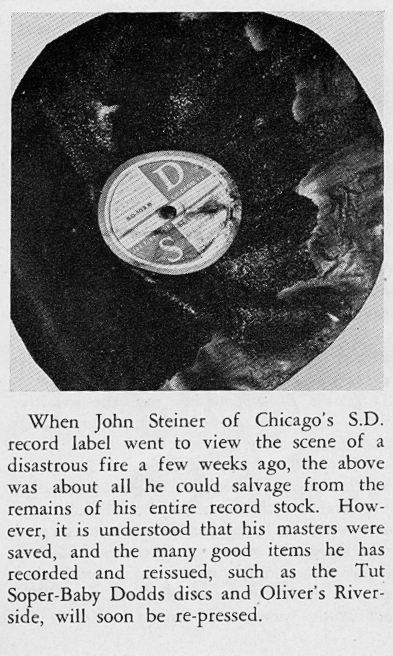

There was another significant hiatus in Steiner's activities after a disastrous fire hit the Uptown Playhouse Theater on April 20, 1946. In his rueful post-mortem, "Records to Burn," he noted that the fire began as the Players were finishing the third act of "You Can't Take It with You."

It reduced the building to a shell. "Along with theater properties were consumed my library and clothes, furniture and office equipment, substantially all of the thousands of records racked in the phono-storage room, the recording studio (more destroyed by inundation than by fire), and every piano in the place, including my upright autographed with the sharp corner of a screw-driver by a host of visitors from Yancey to Slam." (p. 6).

Along with pressings of previous S D releases (but fortunately not their masters) Steiner lost no less than 150 unissued sides by Jack Gardner and his groups (Steiner refers to Gardner as the "musical director for S. D. enteprises since 1941"), 20 sides by groups led by Boyce Brown, a few by Frank Melrose, and location recordings by Gideon Honoré, Zinky Cohn, Punch Miller, Bobby Hackett, Joe Sullivan and Jimmy Yancey, along with many disks recorded from radio broadcasts by big name jazz artists.

Taking the chemist's analytical attitude, Steiner noted that when the 78s were inundated, the labels peeled right off the records pressed during World War II while sticking fast to the pre-war Decca, Columbia, and Victor product. "Wartime shellac compositions blistered upon long contact with dirty water and they became raspy under the needle... A few records of recent pressing, including some Savoy, Philo, and Keynote, after five days immersion, crumbled like clay pies, presumably due to solution of some element in their composition." (p. 17)

"There may be some gain from this experience, especially if this story carries a moral. Records are not to be stored in inflammable buildings. Records are to be copied and the copies widespread" (p. 6).

Sources on the fire: The Jazz Record, June 1946, p. 11; John Steiner, "Records to Burn," The Jazz Record, September 1946, pp. 5, 6, 17.

No doubt helping his recovery from the fire, Steiner was able to get in another recording session. On September 30, 1946, he conducted a marathon outing involving tenor saxophonist Bud Freeman and alto sax player Bill Dohler; Jack Gardner and Tut Soper took turns at the piano bench. Three S D 78s were drawn from it; they were released in March 1947, marking a return to activity for the label.

As a warmup to the September 30 outing, Steiner recorded a concert at the Opera House on September 1 (at least this is the date that Steiner attached to the recordings later on). We don't know the full lineup, but Bud Freeman was featured as a member of a quartet led by pianist Paul Jordan. Two sides were eventually released, though not until Steiner began producing LPs in the early 1950s. We are including them here for completeness.

Paul Jordan (p); Bud Freeman (ts); prob. Mike Rubin (b); prob. Frank Rullo (d).

Opera House, Chicago, September 1, 1946

| C9146-13 | Blop Boose | Paramount CJS105, Classics [Fr] 975 | |

| C9146-17 | Blue Lou | Paramount CJS105, Classics [Fr] 975 |

We got the personnel and the matrix numbers from the Bud Freeman listing in Lord's Jazz Discography. Paramount CJS105 was a 10-inch LP titled Panorama under Bud Freeman's name; Steiner released it in 1953.

Two sides by what was probably the same Paul Jordan Quartet appeared in the Fall of 1946 on Gold Seal 402. These carry matrix numbers in the UB 2000 series from United Broadcasting Studios and appear to have been recorded in September 1946. Precisely because of the UB numbers, however, they do not appear to be from the Opera House concert, as Lord claims in his Bud Freeman section. And Gold Seal identified Paul Jordan as the leader, although Bud Freeman was mentioned on the labels. (There is, in fact, an incomplete listing of the same session in Lord's Paul Jordan section.)

Classics 975 is a French CD released in 1997 under the title Bud Freeman 1946.

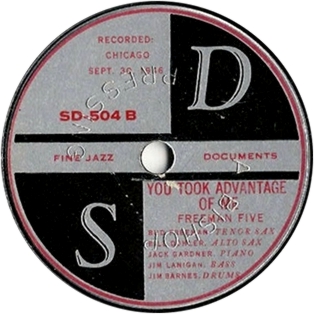

Bud Freeman (ts); Bill Dohler (as); Jack Gardner (p); Jim Lannigan (b); Jim Barnes (d).

Chicago, September 30, 1946

| SD93046-3-1 | Taking a Chance on Love | S D 504 A, Paramount CJS105, Classics [Fr] 975 | |

| SD93046-5-1 | You Took Advantage of Me | S D 504 B, Paramount CJS105, Classics [Fr] 975 | |

| SD 93046-18-1 | Ribald Rhythm | S D 506 A, Paramount CJS105, I Giganti del Jazz [It] GJ34, Europa Jazz EJ 1027, Classics [Fr] 975 |

The copies of S D 504 that we have seen bear the familiar embossing that indicates they were pressed by Bishop. Unlike some other S D's that suffered long delays before release, S D 504, 505, and 506 got moved right along. On December 16, 1946, Steiner wrote to The Bishop Presses from 154 East Ontario street, "Labels are enroute for the our first six sides to be processed and pressed by you." Master numbers, label numbers and titles were provided for all 3 78s. "We shall appreciate fyour every effort to speed test pressings." On January 4, 1947 (shipping date misrendered as 1946), Bishop billed Steiner for over 800 copies of 504 and 505, and 955 copies of 506, at 23 cents a pressing. These were the biggest pressing runs that Steiner is known to have ordered from Bishop; he sent the company a quantity of preprinted labels and asked for as many pressings as labels. Typically the numbers for a particular single were between 2 (really) and 300 copies.

Of all the Bud Freeman sides released by Steiner, S D 504 got the most favorable mention by the Down Beat reviewer, who was not the ever-pliable John Lucas. It didn't hurt that "You Took Advantage of Me" was an old favorite of Freeman's; he had given it a memorable performance in 1938 for Commodore, and would record it on several other occasions. Awarding the 78 three of the four possible quarter notes, the reviewer noted that both numbers swung "consistently with both reed men attempting good consistent improvisation."

"Ribald Rhythm" on S D 506 got a two-note review and the Down Beat scribe noted that the number was actually "Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea."

John Lucas praised the sides in his "Jazz on Record" column in the Record Changer (April 1947), lauding Steiner for a "novel and stimulating idea," that is, using alto and a tenor sax as the "whole melody section in collective improvisation." He said S D 504 found Dohler on alto and Freeman on tenor "weaving some of the most complex patterns conceivable, and with complete spontaneity."

The Freeman 78s on S D 504 through 506 remained in stock until at least 1952, when a booklet included with the first 10-inch Paramount LP release still advertised them for sale.

Finally, though, they were superseded by a 10-inch LP that collected the 6 tracks from this session and 2 from September 1. Paramount CJS105 was called Panorama under the artist name Bud Freeman; Steiner released it in 1953.

Classics 975 is a French CD released in 1997 under the title Bud Freeman 1946.

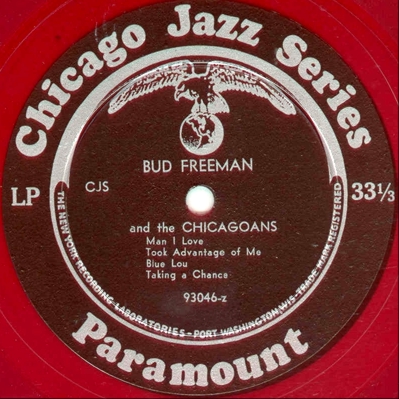

Bud Freeman (ts); Jack Gardner (p); Tut Soper (p-1); Jim Lannigan (b); Jim Barnes (d).

Chicago, September 30, 1946

| SD-93046-11-1 | The Man I Love -1 | S D 505 A, Paramount CJS105, Classics [Fr] 975 | |

| SD 93046-18-1 | Ontario Barrel House* | S D 506 B, Paramount CJS105, I Giganti del Jazz [It] GJ34, Europa Jazz [It] EJ 1027, Classics [Fr] 975 |

Lord gives the artist names as Bud Freeman Quintet and Bud Freeman Quartet. We are using the names as they appeared on S D 504, 505, and 506. See above for the pressing history on these three; Steiner ordered 800 or more copies of each in mid-December 1946 and had them in his hands in January 1947. Paramount CJS105 was called Panorama and the artist's name there was plain old Bud Freeman on the jacket, Bud Freeman and the Chicagoans on the labels; Steiner put it out in 1955.

Lord also identifies 3 of the tracks that appeared on the 10-inch LP as different takes from those released on S D. But according to Bud Freeman expert Tom Hustad, no alternate takes have survived, and Steiner's Paramount LP was a straight reissue of the S D sides (with the two from September 1 added).

Classics 975 is a French CD released in 1997 under the title Bud Freeman 1946.

The Down Beat reviewer gave both numbers two quarter notes out of a possible four. "The Man I Love" was criticized for poor mike placement and Freeman’s "unsteady" tone, and "Ontario Barrel House" was faulted for Freeman’s "honkey" tone and Gardner’s right hand lacking "technical freedom." Lucas, on the other hand, thought that "Ontario Barrel House" and "Ribald Rhythm" (S D 506) was the best of the three couplings.''

According to Hoefer, "Ontario Barrel House" is named for the street where the apartment that Steiner and Gardner shared was located. We checked the phone books from the period and could not find either Steiner or Gardner at that address. But they had left Bellevue Place, and the apartment that Steiner maintained at the Uptown Playhouse had been destroyed in the fire. In fact, Steiner's letter to Bishop on December 16, 1946 was mailed from 154 East Ontario. In January 1947, received a bill from Bishop at the same address. He seems to have moved to 8 South Dearborn before June 1947.

Bud Freeman was born Lawrence Freeman, on April 13, 1906. He is one of the famed members of the Austin High School Gang, and helped put Chicago on the map as a jazz center in the 1920s, playing with his schoolmates in the Blue Friars and then the Wolverines. He began on the C Melody sax in 1923, and switched to tenor sax in 1925. During 1926-27, he played in various Chicago bands, and then moved with Ben Pollack’s band to New York City in 1928. In 1929 Freeman was touring with Red Nichols. Early white jazz was gimmicked up with sound effects, and Freeman is credited with being one of the first white tenor sax players to free himself from the novelty approach (black tenorists, led by Coleman Hawkins and Prince Robinson, also had to escape the pull of the once-omnipresent "slap-tonguing" technique). During the 1930s, Freeman recorded extensively with such bands as Paul Whiteman, Tommy Dorsey, and Benny Goodman. He established his own band in the late 1930s, performing in a style that combined Swing with traditional Chicago style. From 1943-45, Freeman was in a service band, and upon becoming a civilian in the summer of 1945 formed his own band. He was under contract to Majestic for a year, but the experience was unsatisfactory because his band was mainly called on to back vocal groups, producing several records with no real jazz content.

As one of the titans of early jazz, Freeman was frequently recorded during the 1940s and 1950s. He had a long residency in Chicago at his own Gaffer’s Club in 1949. In the late 1970s he was living in London, but returned to Chicago when invited to appear in the Chicago Jazz Festival in 1980. He retired from performing in 1989, and died in Chicago on March 15, 1991.

Freeman sources: John Chilton, Who’s Who of Jazz: Storyville to Swing Street (Philadelphia: Chilton Book Company, 1972): 125; R. Bruce Dodd and Jerry Crimmins, "Lawrence ‘Bud’ Freeman, Chicago-Style Jazz Legend," Chicago Tribune, 17 March 1991.

Bill Dohler (as); Tut Soper (p); Jim Lannigan (b); Jim Barnes (d).

Chicago, September 30, 1946

| SD93046-17-1 | Blue Lou | S D 505 B [edited], Paramount CJS105 |

The copies of S D 505 that we have seen were pressed by Bishop in South Pasadena, California. See above for the pressing history on S D 504, 505, and 506, which were done by Bishop in late December 1946 or early January 1947 (Bishop's invoice to Steiner was dated January 4, 1947).

Dohler's opening statement (running to 22 seconds) was edited out of the original release, which starts with Soper's first piano solo. On the Bud Freeman LP (Paramount CJS 105), the track is complete.

The Down Beat scribe, "Mix," who reviewed the number with its flip, "The Man I Love," gave the number two notes out of 4, and faulted poor mike placement that kept Lannigan’s bass from coming through. (In fact, Barnes' bass drum is louder than the string bass.) Similar to his comments on Gardner, he appreciated Soper’s enthusiasm, but thought he needed more "technical surety." Lucas, in contrast, was more taken with Gardner and Soper than "Mix," gushing, "these records are priceless if only because of the electrifying work of Soper and Gardner."

The entire package of 3 S D releases was reviewed in George Avakian's column in the May 1947 issue of The Jazz Record. Alluding to the long pause since the last S D release, Avakian referred to the 78 as the company's "first post-war release in the form of three records featuring the tenor sax of Bud Freeman and the alto ditto of Bill Dohler... with a three-piece rhythm section" (p. 7). It really was the first postwar release, the product of Steiner's first pressing order with Bishop. Avakian's assessment of the music was that the 78s "have a distinct jam-session flavor, and should appeal most to those who get a great kick out of these affairs. They are two-fisted improvisations, emotional rather than calculated, on familiar standards" (p. 8). Avakian thought that "Ribald Rhythm" wasn't quite up to the same level as the others, because the (unnamed) standard on which it was based "never was much of a jazz vehicle" (p. 8).

Bill Dohler had been performing since the late 1920s, when he got together with his former classmates from Lake View High on the far north side of Chicago—Lake View High Gang doesn’t have the same ring as Austin High Gang. He bounced from band to band, playing for example in the 1930s Earl Hoffman band out of Louisville.

Avakian commented that "Dohler, who is new to me, and probably a stranger to most readers, too, plays quite like Bud, and on the sides in which they improvise duets it's hard to tell which instrument is which" (pp. 7-8).

We know hardly anything about Bill Dohler's later activities. Bill Dohler also played alto sax in an octet led by Paul Jordan that recorded for Gold Seal in September 1946. This was a studio recording at United Broadcasting; the Paul Jordan Octet single on Gold Seal 403 carries matrix numbers in the UB2400s. Bud Freeman did not participate in the octet session, which featured Boyd Rolando as the tenor saxophone soloist.

S D 505 remained in Steiner's catalog until at least 1952. The entire session, Dohler's solo feature included, was reissued on a 10-inch LP in 1953. Paramount CJS105 was called Panorama under the artist name Bud Freeman and the Chicagoans.

The decision to exclude Bill Dohler's side from a Bud Freeman compilation (Classics 975) had its logic, but it has left this one excellent performance without any reissues on CD.

Sources Used: George Hoefer Jr., "The Hot Box," Down Beat, 26 February 1947, p. 12; Mix, "Diggin’ the Discs," Down Beat, 26 March 1947; John Lucas, "Jazz on Record," The Record Changer 6/2 (April 1947): 10; George Avakian, "Records—Old and New," The Jazz Record (May 1947), pp. 7-8; Booklet included in Paramount CJS101, released in 1952, courtesy of Konrad Nowakowski.

In addition to the 5000/500 series, S D put out a special 78 Christmas 1946, drawn from a Duke Ellington concert that Steiner had recorded at the Civic Opera House in Chicago. If it was released around Christmas 1946, that made it the first S D release since the fall of 1944; releases in the 500 series would not begin until the spring of 1947. The first sign we've spotted of the Xmas 46 record is a bill from The Bishop Presses on March 11, 1948—for 25 copies. On April 26, 1949, Steiner ordered more copies of the Xmas 46 record, but made it clear that it wasn't a priority ("their [sic] simply experimental lots") and that it could be done on "Flex." or Vinylite at Bishop's discretion.