Revision note:We have clarified the timing of Max Miller's two sessions (for Life and then for Columbia) in 1950. We have added a little about Life's pickup in activity at the beginning of 1952, about the original RCA Victor releases that correspond to Life 1013/5003 and 1014/5004, and about the company's last feeble sign of activity, in March 1953. We have added information about (what was probably the second) Life 1001, by Singing Tom and the Twilighters. We are still upgrading our coverage of multi-instrumentalist Max Miller, taking advantage of the extensive file on him in the John Steiner collection at the University of Chicago Library. We have seriously upgraded our coverage of Lucille Fanolla (aka Gloria Van), the singer who was responsible for Life 1002. She made three singles that we can verify before her 1950 session for Life, and four afterward

Life Records, an independent label in operation from 1948 into 1953, was an obscure Chicago enterprise, run on the side by an executive at a music publisher. The company is of interest today really for just one reason, because it recorded a maverick jazz musician named Max Miller. Miller was somewhat of a legend in Chicago. He got offers from major labels from time to time, but throughout his career accepted just one of them, because he did not want to give up ownership or control of his original compositions. Consequently, his commercial recordings would be few and and sporadic.

Owned by W. W. Maloney, a music publishing executive, the Life company was located in the Garrick Theater buidling at 64 West Randolph Street in the Loop. It opened for business in August 1948, took 18 months to get three releases out, and didn't begin working with Max Miller until April 1950.

Life has gotten little attention in the past. Its total output was tiny (10 releases that we know of) and its distribution not much to talk about. From 1950 through the middle of 1952, it was handled by Art Sheridan's American Record Distributors in Chicago, but there was no oomph behind its records anywhere else. For a while, Max Miller would sell what was left of the company's stock out of his studio. It was not strictly a jazz label, and the jazz sides by Max Miller and his various groups were interlarded with pop vocal and instrumental material of lesser interest today. Maloney wasn't interested in rhythm and blues, and like many of the older White jazz musicians in Chicago, Miller had no connection with that scene—though as a veteran radio man he did appreciate the importance of DJ Al Benson.

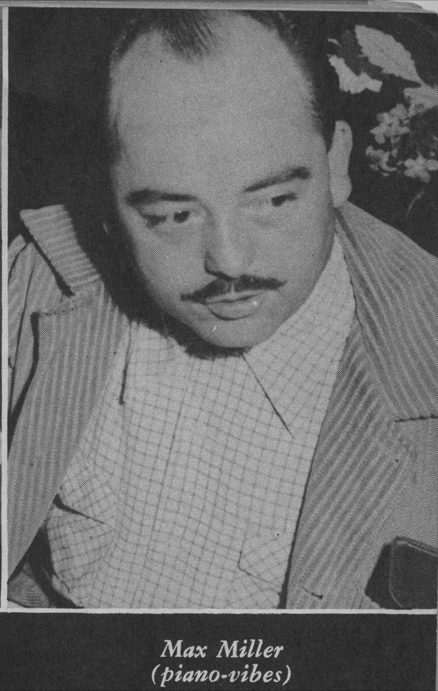

Multi-instrumentalist Max Miller was born Edward Maxwell Miller, on November 17, 1911 in New Philadelphia, Ohio. His family moved to East Chicago, Indiana, when he was 12. His first instrument was the banjo, which he played in the East Chicago High School band. He joined Local 203 (Hammond, Indiana) of the Musicians Union in 1927, at age 16; around this time, under the influence of Eddie Lang, he switched to guitar, playing in regional jazz groups. From 1928 through 1932 he gigged with various bands in Indiana and Michigan, also getting married for the first time, to Peggy Ludlam, who was from Michigan. In 1933, he wasn't earning enough to support his family—he and Peggy had three children—so he worked full-time in a foundry, in a filling station, and as a Fuller brush salesman, also selling radios and refrigerators. "I quit the righteous life in 1935," he told Music and Rhythm (March 1941, p. 68). "I packed my belongings into a trailer and went to Chicago. I had no instruments, no union card."

His first gig was as a drummer; when he joined Phil Dooley's band, he first played string bass, then told the leader he'd play the vibraphone as long as he was furnished with an instrument. In all of his interviews, he claimed to be self-taught on every instrument. Among the musicians with whom he worked in his early days were drummer Dave Tough and pianist Kansas City Frank Melrose.

He toured with the Vincent Lopez Orchestra, playing mostly guitar but doing some feature numbers on the vibes. He left Lopez in 1937 to become the musical director at radio station WIND, performing 15-minute live shows 6 nights a week. These often featured his original compositions. Leaving the radio job in 1939, he headlined at the Off Beat Club, run by a Down Beat editor in the basement underneath the Three Deuces. His vocalist was Anita O'Day. They would work together on several other occasions in the 1940s and early 1950s. In 1940, Miller led a quintet at the Three Deuces, on which he played vibes and Johnny Bothwell played alto sax. The gig ended when the club burned down. Subsequently, he became the music director for Boyd Raeburn's big band for a time.

In February through April 1941 Miller led a trio at Benton's Grill on Lake Street. He played vibes; Herb Lawson (who had replaced Sid Fisher) was on guitar and Ed Mihelich on bass. A photo of the trio is included in the first article about him, "'Musicians are Lazy and Jam Sessions Are the Bunk!' Night club owners tell Max Miller his band is fine, but they want him to 'take out his teeth,'" Music and Rhythm, March 1941, pp. 64-68. Supposedly the work of one "Tom Palmer," the article was actually written by Paul Eduard Miller.

Early in 1943, Miller was in a group led by trumpet player Shorty Sherock at Elmer's Room. Located at 186 North State Street, Elmer's was across the street from the Chicago Theater and the Capitol Lounge. Miller was still playing the vibes at this point, but in the two years since it opened Elmer's had developed a particularly strong reputation "as a jumping off deal for solo pianists," according to Metronome writer George Hoefer Jr. Hoefer noted that such jazz keyboardists as Dorothy Donegan, Robert Crum, and Mel Henke first came into the limelight performing there.

In March, 1943, Max Miller temporarily dropped out of music. He was turned down for military service and wanted to aid the war effort, so he got a job in a factory manufacturing airplane parts on the other side of the lake, in St. Joseph, Michigan. He dedicated himself to learning piano in his off-hours.

By the summer of 1944, his job at the factory was more white collar (he had been promoted to sales engineer), and he was leading a trio in Benton Harbor, Michigan, which included Ken Smith on drums. In August 1944, he and jazz critic Paul Eduard Miller (no relation) drove all the way to Springfield, Illinois, to take in a performance by Sidney Bechet, who was doing a return engagement at Club Rio, an Italian restaurant run by Vito Impastato. Paul Eduard Miller (1902-1972), who had been a major Bechet booster for a decade, would become Max Miller's biggest sponsor over the next several years.

Paul Miller had been urging Max Miller to meet Bechet for some time. Ken Smith was driving a truck for a milk company; it was hard to travel on the highway during World War II because gasoline and tires were rationed, and the national speed limit was 35 miles an hour. He and Max Miller drove 100 miles to Chicago in the milk truck to pick up Paul Miller.

We picked Paul up there and then went on to Springfield, Illinois, about another 250 miles. We got there in the middle of the night, or so it seemed, but Sid was still blowing at the club, and after we were introduced we sat in and we played for the rest of the night. We hit it off straight away and later, whenever Sid came to Chicago, we usually had a session. (Max Miller, interviewed by John Chilton, in Sidney Bechet: The Wizard of Jazz, New York: Oxford University Press, 1987, p. 158).

Thereafter, Max Miller would make his way to Chicago on Sundays to make private recordings with Sidney Bechet, Ken Smith, Bill Funkey (alto and tenor saxophone), Zilner T. Randolph (trumpet and composer), and Tony Parenti (clarinet). His first session with Bechet took place on October 8, 1944, after Bechet wrapped up the gig in Springfield; John Steiner and Hugh Davis did the recordings. On November 15, Down Beat reported that the session had been recorded at someone's home, with Paul Eduard Miller presiding. All numbers were performed by a trio, with Kenny Smith at the drums.

In its issue of September 15, 1945, Down Beat ran an article trumpeting, "Max Miller Returns to Music as Pianist." The Billboard of the same date announced that "Max Miller has quit his war job and is 88-ing at Elmer's, Chicago" (p. 32). His first gig was at Elmer's Room, playing solo piano. In November 1945, "prominent young guitarist" Jimmy Raney joined him.(Billboard, November 10, 1945, p. 32).

On December 15, 1945, Billboard ran an article about jazz critic Paul Eduard Miller's efforts to emulate other jazz in concert presentations that were "cleaning up plenty moo." For an Orchestra Hall concert scheduled for December 17, "Only well-known jazzman on the first date is Sidney Bechet, the New Orleans reed ace, with the remainder: Tony Parenti, white, N. O., clary; Bill Funkey, Gary (Ind.) alto and tenorman; Max Miller, Chi pianist corrently fronting his own cocktail trio; Kenny Smith, drummer, and several other unknowns filling out the program. Ducats are scaled from 95 cents to $3.00 for boxes" ("Chi Trying to Build a Jazz-Star Center," p. 18).

As it turned out, neither Bechet nor Parenti was available when the concert took place, so Muggsy Spanier, a pretty famous jazzman, was engaged as a replacement. Mickey Simms, of the Red Saunders band, was the bassist, and Jimmy Raney, who had been working in Miller's trio, was the guitarist.

Apparently uninterested in Miller's schemes for blue bitonality—he explained to Music and Rhythm how a 12-bar blues in G that started on a flatted ninth chord would support soloing in G or in D flat as the soloist preferred—John Steiner, who took notes during the concert, wrote "Same Old Blues" after the titles of several items.

The January 1946 Phil Featheringill column in Metronome indicates that Miller was still at Elmer's, noting that Ken "Smitty" Smith was now installed in the drum chair. Featheringill further noted the December concert. The March 1946 Phil Featheringill column indicated that Miller was at Elmer's, performing in a trio, with Joe Broccolo as his new drummer. Around September of 1946, Miller was playing at the Cowboy Lounge.

In October 1946, Jack Green announced that he had recorded two artists, the Paul Jordan Octet and Max Miller. Miller, it was said, had cut some original compositions on piano and some on celeste. He was backed by Buddy Nichols on bass and Andy Nelson on guitar. The announcement was that these would be coming out on a label called Green Records. No such thing happened.

Instead, two tracks by the trio showed up on a short-lived, eclectic Chicago imprint called Gold Seal.

As it turns out, the Max Miller sides had been recorded in August. Any announcements from Jack Green would be postponed. However, on September 29, Paul Eduard Miller presented "a jazz concert in the intimate manner," at 3 PM in Kimball Hall. According to the announcement in the Chicago Sunday Tribune (September 29, 1956, part 6, p. 5), the musicians were Ford Canfield, Dean Schaeffer, Porky Panico, Ken Smith, Mel Henke, Joe Rumoro, Max Miller, and Buddy Nichols.

Green did manage to accomplish a little bit of recording and a little bit of concert promotion. In its issue of October 12, 1946, Billboard ran a story titled "Real Estate - Jazz Concert Op Forms New Chi Diskery."

"Chi's biggest jam session ever" was planned for the Civic Opera House on October 13. "John C. Green, industrial-real estate op who dabbles in concert promotion, heads the diskery. Aided by Paul Edouard [sic] Miller, the jazz critic, he has rounded up 22 jazzmen, including Sidney Bechet, Gene Cedric [sic] and Dizzy Gillespie, who'll fly in for one-nighter, together with Paul Jordan, Max Miller Trio and Bud Freeman, latter three being stars of Green's first releases. Green plans to have Freeman Quartet, Miller Trio and Jordan's Octet do numbers at concert, which they do on first Green issues, plus other numbers by the 22 jazzists. If Green gets good reaction to any numbers on program which haven't been waxed, he plans to have John Steiner, former head of S. & D. platters on hand to record them after the show" (p. 35). The September 29 announcement in the Tribune had mentioned the October 13 show as upcoming, with the same artists (Sedric's name was misspelled the same way) plus Jimmy McPartland and Geroge Barnes.

The article mentioned a follow-up concert to take place at Kimball Hall on October 26, "when Boyd Rolando, tenor find, heads a mixed group of jazzmen." In fact, the next concert was postponed till November 9; it appears that this event and its follow-up on December 1 reverted to being strictly Paul Eduard Miller's responsibility. The story even gives a succinct explanation why Green Records wasn't going to make it: "Green plans to confine the catalog strictly to jazz. Deal has been made for a Midwest pressery to handle disk production, but distribution problems still confront the firm."

Gold Seal had been launched just a couple of weeks earlier, by Leonard Klein, who had been with United Broadcasting Studio. During its roughly 24 months in business, Gold Seal did a small amount of new recording and got its other releases from other independent labels that had gone out of business. The three 78s that been intended for release on Green Records were the company's first acquisition, and rounded out what there was to its jazz series.

It's doubtful that Paul Eduard Miller, who had brought Max Miller to Green Records, was satisfied with this outcome. Max Miller would get just one release on Gold Seal, which discontinued the 400 series after three singles. But it was a musically significant release, his first commercial recording as a leader, and the first recorded performance of one of his own compositions.

Max Miller (p); Andy Nelson (g); Buddy Nichols (b).

Bachman Studio, Chicago, August 1946

| 6 | Heartbeat [Heartbeat Blues*] (Miller) | Gold Seal 401, Life L-B-1003* | |

| 7 | Caravan (Ellington-Tizol) | Gold Seal 401, Life L-A-1003 | |

| Berta's Bounce | Green (unissued) | ||

| Tune on My Mind | Green (unissued) | ||

| Blues for Beethoven | Green (unissued) | ||

| These Foolish Things | Green (unissued) | ||

| Fantasia of the Unconscious | Green (unissued) | ||

| One Way | Green (unissued) | ||

| Sweet Lorraine | Green (unissued) | ||

| Carmen Av. Special No. 1 | Green (unissued) |

The Max Miller sides on Gold Seal 401 show an unadorned 6 and 7 for matrix numbers, suggesting that they originated from a single session away from any of the main commercial studios. Most likely, Miller, who was already used to organizing his own sessions, was in charge of this one all the way. The title "Carmen Av. Special No. 1" points directly at the Bachman Studio. We had estimated the date as September 1946, but in his interview with John Steiner (August 7, 1958) Miller recalled it as August.

The Green Recordings concert program for the Civic Opera House, October 13, 1946 (see below), listed no fewer than 9 unissued Max Miller Trio items. "Heart Beat Blues" was said to be ready for "late October release"; "Caravan" was not mentioned (unless it was given some tricky retitle). "Berta's Bounce" and "Tune on My Mind" were also said to be scheduled for release in late October 1946; the others were listed as "For Future Release." The implication is that Miller had cut 10 sides for Green Records (maybe 11, if "Fantasia of the Unconscious" was as long as his 1950 rendition would be) and only 2 would ever see release. Also, we can see that Gold Seal made different picks from Jack Green.

The two standards on this session, "These Foolish Things" and "Sweet Lorraine," were not revisited when Miller cut an all-standards LP for Columbia in 1950. "Fantasia of the Unconscious" was rerecorded for Life that year.

"Heartbeat" is a minor blues, the same Max Miller composition that was called "Heartbeat Blues" in some of his contemporary press coverage, that appeared under that title at his concert of December 17, 1945, and was referred to as "Heart Beat Blues" on the concert program for the October 13 outing at the Opera House. On reissue in 1950, it would be titled "Heartbeat Blues." One passage in "Hearbeat" prefigures Mal Waldron, another sounds uncannily like the work of Randy Weston; neither, of course, was making any records in 1946. "Caravan" was already a jazz standard by this time. Miller plays with such verve and power that Nelson's rhythm guitar and Nichols' bass could easily be missed by a casual listener. But Nelson's quietly insistent rhythm makes up for the absence of a drummer.

Gold Seal 402 and 403, both by groups led by pianist Paul Jordan, were recorded at United Broadcasting, a venue Leonard Klein would keep using as long as his company was in business.

A long biographical profile by George Hoefer, Jr., in Metronome (December 1946), put Miller back at Elmer's, playing solo again. Hoefer explained that "for a while Max worked with Jimmy Raney on electric guitar, a bass, and several drummers." Raney had been with Miller at the December 17, 1945 concert; Andy Nelson replaced him before the recordings for Green took place.

In the notes to his Columbia LP, Miller is said to have spent a year and a half in California during the late 1940s. This is verified in the John Steiner interview; apparently Miller got out of town not long after he realized that Green Records wouldn't be going anywhere. A sojourn far away would have helped him get his mind off all those unreleased masters. Meanwhile, Paul Miller featured Sidney Bechet in two concerts at Kimball Hall (and had both of them recorded). At the aforementioned event on December 1, Bechet was accompanied by Ray Dixon on piano. On January 26, 1947, Fletcher Henderson was booked to accompany him.

Unlike Green, Gold Seal was not meant to be a jazz label primarily. Gold Seal put out three 78s by legendary pianist Robert Crum, known for his interest in lengthy, essentially free improvisations, and, toward the end of its run, picked up some Valaida Snow sides from another defunct record company called Bel-Tone. It also recorded singer Arthur Lee Simpkins, who included some jazz numbers in his repertoire, but may not have done them for Gold Seal (Simpkins is supposed to have had one release out, but we haven't found a copy). But the rest of Gold Seal's activity was in pop organ-piano music (featuring Kenny Jagger, then in much demand as a "cocktail single") or in Country. As the second Petrillo recording ban hit, on January 1, 1948, Gold Seal was in trouble. The company got its last writeup in Billboard on February 14, 1948. Its last months were devoted to Country reissues. By the end of the year, iit had sunk without a trace.

His Green/Gold Seal experience now behind him, Max Miller returned to Chicago in the middle of 1948. He experimented for a while with larger groups before returning to a trio format.

Ted Hallock's column in the August 11, 1948 issue of Downbeat did not sound too impressed with Max Miller's sextet:

Max Miller's unit, backing Boot Whip, is probably the worst he's had, notable for a trombonist who shouldn't be playing for money, period. Personnel includes Remo Belli (drums), good; Ralph Gephardt (bass), eager; Hal Blondstein (trumpet), who can't play like Diz but tries; Bob Gillett (alto), excellent; and Jay Kelliher (trombone), oh my. Miller, Kelliher, Belli, and Blondstein are on a new kick....the "pukka bloke" facial adornment. May replace the goatee.

A quintet lineup can be seen in a photo taken at a Milwaukee club in 1948, where Jay Kelliher and Max Miller are the "pukka blokes." Instead of Hal Blondstein, Tommy Allison is on trumpet. A photo taken during the same engagement, but probably not on the same night (the three horns are positioned differently on stage) shows Anita O'Day as the vocalist. "Hi Ho Trailus Boot Whip," on Signature, was her latest record.

On January 28, 1949, the Max Miller Trio opened a new club in the near North Side, the Hi-Note, at 450 North Clark Street. The Hi-Note was generally thought to be owned (or co-owned) by Anita O'Day. During this engagement he worked with Earl Backus on guitar and Buddy Nichols on bass (a postcard announcing the engagement is in the John Steiner Collection). For two weeks at the Blue Note starting on March 28, Miller added four pieces, backing Mel Torme. On April 11, the trio resumed at the Hi-Note. On June 16, 1949, Max Miller married for the second time. His new wife was Jeanne O'Brien, whom Billboard described as "secretary to Tweet Hogan, local act booker" (June 18, 1949, p. 22). She would be involved in promoting him for the next few years.

Life Records opened for business in August 1948. Its owner, who ran a music publishing company, started a record company because he wanted to get some of his own tunes recorded.

Chicago, 1947 or 1948

| Baby (Maloney) | Life A-1001 [?] | ||

| Old Rendezvous (Maloney) | Life B-1001 [?] |

What we know about this release comes from the August 21, 1948 issue of Billboard. One of the trade paper's Chicago items ran as follows:

W. W. Maloney, chief of Chicago Music, BMI affiliate, bowed with his Life Record label, with the first platter featuring the Three Kings and a Queen, Michigan cocktail combo, doing Maloney's Baby and Old Rendezvous, first of a backlog of masters on Maloney's original tunes. (p. 21)

We're not sure how seriously to take this "backlog" language. It's possible that Maloney had paid for a session and couldn't get any existing company to release the sides; in addition, he might not have wanted to alert the Musicians Union to new recording activity while the second Petrillo ban was still officially in effect.

We still haven't seen a copy of the first Life single, which we infer is the rarest of the lot. But now that we know that the next Life single had sides denominated C-1001 and D-1001, we figure the first one was also a Life 1001.

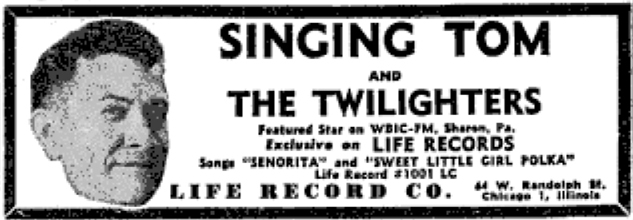

Not a whole lot happened over the next year. Pent-up demand for W. W. Maloney's compositions, it had turned out, was minimal. On July 30, 1949, Cash Box (p. 18) ran a teaser ad promising two new releases. In September 1949, the company's address was still 64 West Randolph Street, in the Loop. And what looks like the second Life 1001, featuring a polka band singer from Pennsylania, was advertised in the September 24 issue of Billboard. It was listed as a new release in the same issue (p. 36). All right, there was new release…

Personnel unidentified

Chicago, c. September 1949

| Senorita [sic] | Life L-C-1001 | ||

| Sweet Little Girl Polka | Life L-D-1001 |

On October 1, 1949, the second Life 1001 got one of the worst reviews ever handed out by Billboard (p. 34): four 25's out of 100 for "Senorita." "Senorita" was identified in the review as coming from a film, so it wasn't a Maloney composition. The labels show no composer credits at all.

Our estimate is that Life recorded and released 14 sides from 1948 through 1950, all of which appeared on 78 rpm in a 1000 series. Six sides were performances of original compositions by Max Miller. However, Life nearly always used its scarce ads in the trade papers to flog pop singles.

In any event, Life was not pursuing what anyone would consider an aggressive release schedule: 1002 wouldn't be coming along for nearly six months. Meanwhile Max Miller held down a gig at Rossi's New Apex Club, where he would remain for much of 1950. His association with the company was yet to begin.

On February 18, 1950, Billboard's Chicago music items included "Life Records here is going into 45 r.p.m., according to A. T. Maras, the firm's recording chief. Ray Magee has been appointed Eastern division manager for the diskery" (p. 43). That would have been bright and early for a small indie. In the end, all four known 45s from Life were done in 1952.

Our knowledge of Life 1002, a pop single, is based on a Billboard ad that ran on March 4, 1950, and the review that Billboard ran on March 18. It would be nice to find a copy.

Gloria Van was born Lucille F. Fanolla, in Alliance, Ohio, on August 17, 1920. Her family moved to Chicago when she was a girl. In 1929, her father, a baker, was killed by Al Capone's gang. He was selling yeast to two mobs, both of which used it to make illegal beer, and Capone's had demanded an exclusive deal. She attended Bowen High School. She was working at the cookie counter in Goldblatt's when she was discovered by her manager: she had been asked to sing at the store's holiday party. She began singing at Siegel's Barbecue Stand on the South Side, then at Knowle's Cafe in Hyde Park. One of her early gigs, at Cafe Tomorrow on Halstead, was in a show that featured a stripper. Probably in 1940 (her interviews sometimes gave an earlier date), she worked the Glass Hat at the Congress Hotel, where she met James Lynn Allison (born in 1912), a saxophonist and singer in Jerry Shelton's combo. (Lynn Allison remembered meeting her while they were in Scat Davis's band). He was the brother of singer and future TV puppeteer Fran Allison. Gloria Van was singing a rhumba (Shelton, an accordion player formerly with Shep Fields and His Ripplin' Rhythm, backed a Latin dance team for nearly ten years) and the leader thought it needed a male duet partner. When Shelton went on the road—he ended up spending a lot of time in California—Gloria Van left his band.

Probably from late 1940 through the end of 1942, she sang in Johnny "Scat" Davis's band. (She was occasionally mentioned in publicity for the band; for example, when Davis played in the Oriental Theater along with the Mills Brothers, Chicago Tribune, December 5, 1941, p. 32). Billboard reviewed a live performance.) After two years with Davis, which included a lot of traveling, she was stranded in California when Davis got an offer to make a B movie (Sarong Girl) with Ann Corio, decided he could use the money, and deactivated the ensemble. If she appeared in a Paramount short with Scat Davis, as a 1949 article on her later asserted, then Gloria Van got something out of the the West Coast trip.

Gene Krupa conducted a series of raids while Davis was otherwise occupied. Gloria Van spent long enough in Ted Fio Rito's orchestra, which was doing a series of engagements on the theater circuit called Interstate Time, to get from California to the East Coast, then went with Gene Krupa's. She replaced Anita O'Day in February or March 1943. Gloria Van and Lynn Allison were married on March 30, 1943, between shows at a theater in Pittsburgh, while both were singing with Krupa. Krupa was busted in May, for allegedly getting his valet to buy marijuana for him; his band did not shut down immediately, but we are not sure how much longer Gloria Van stayed in it. In November 1943 she moved to Hal McIntyre's band, replacing Helen Ward, who had joined Harry James' band. After her husband was drafted he ended up working with Glenn Miller's Army Air Force band and his Crew Chiefs in England; one day in December 1944 he drove Miller to the airstrip, but fortunately for him did not board the plane that went down over the English Channel. Meanwhile, Gloria Van stayed with McIntyre into February 1945, then worked a show in the Cincinnati area for several weeks and returned to Chicago. She initially lived with her sister-in-law, Fran Allison, who was then performing on radio on "The Breakfast Club."

While such bands as Krupa's and McIntyre's had been doing a lot of recording, Gloria Van was with them while the first Petrillo recording ban was in effect.

When Lynn Allison came home from the war, Gloria was onstage at the Chicago Theater, singing "It's Been a Long, Long Time." Lou Breese was supposed to make his entrance, but Lynn had just arrived and Breese sent him out on stage in uniform.

She started a sextet called the Vanguards, subsequently reduced to a 3-man Vanguard vocal group (with her husband singing tenor). With the vocal-group Vanguards, she had her own weekly radio show on WBBM for two years, from September 21, 1946 through September 1948; for much of 1947 they were billed as Cinderella and Her Fellas. When WBBM didn't renew the deal, she and the Vanguards joined Buddy DiVito's big band for a spell (October 1948 through February 1949; Billboard announced she had joined DiVito on October 1, 1948, p. 44). WBBM then hired a new vocal quartet, the Meadowlarks, which just happened to include ex-Vanguard Maury Jackson. Gloria Van led another combo of her own for a while in 1949, and appeared on an ABC TV show, her first.

Gloria Van first recorded in 1947 for some tiny label (resulting in a single on Master; if this was a typical Master release, the tiny label had been delinquent on a studio bill at United Broadcasting). All we know about it is that the titles were "My Town" and "The Soap Box Serenade"; it hit the Billboard Advance Record Releases during a week when someone was in a hurry and gave the names of the companies without the issue numbers (November 15, 1947, pp. 31-32). It would be nice to see a copy, but it must be ridiculously rare. Shortly thereafter, she and the Vanguards put out a single on Universal. Universal put some promotion into this one. We have a company ad for Universal 34, "All Dressed Up with a Broken Heart" b/w "Cindy" (Billboard, November 29, 1947, p. 28), and a review of her single in Billboard for December 20, 1947 (p. 98). Among the performers featured in the same Universal ad was her former employer "Scat" Davis (Universal 17).

Probably in February 1949, right after the Vanguards broke up, Gloria Van and the black vocal group the Four Vagabonds recorded a single for a tiny label called VRT (our thanks to Andy Bohan for information about this highly obscure release, which was featured on the Vocal Group Harmony site Vocal Group Record of the Week #833, February 28, 2015, http://www.vocalgroupharmony.com/4ROWNEW/IThoughtYouTold.htm). The Vagabonds (John Jordan, lead tenor; Norval Taborn, baritone; Robert O'Neal, tenor; and Ray Grant, Jr. (bass and guitar) had been inactive for about a year, and had just gotten back together around this time (see Rick Whitesell, Pete Grendysa, George Moonoogian, and Marv Goldberg, The 4 Vagabonds). More was likely done for VRT, but if so the sides are untraced.

Both songs were written by Rose Mary Trabucco, who might in fact have contributed two letters to VRT, and Bill Walker. At the time William Stearns Walker (1917-1994) was writing songs, playing the piano on WIND in Chicago, and leading a society band whose highest-profile gig was off-nights at the Pump Room. One of the few records he made under his own name was for Aristocrat in 1950; two more were done for Rondo in 1950 or 1951. In 1953, Walker went into the field where he found lasting success, writing and producing music for commercials.

To avoid road tours and their strings of one-nighters, Gloria Van often worked in shows that ran for a month to 6 weeks at the same venue. In October 1949, she was featured in "Salute to Rodgers and Hammerstein" at the College Inn at the Sherman Hotel, enjoying extra stability in a show that had been running since May (it got a positive review from Johnny Sippel in Billboard, May 28, 1949, p. 42). Somebody at Cash Box liked her performances, because the trade ran a short article reminding readers that "The gal is not only a 'looker' but has a pair of pipes that are sure to bring her renown from all who hear her" and encouraging record companies to sign her ("Record Potential," Cash Box, October 15, 1949, p. 15). The bio mentioned her big band and radio work, but just one of her prior recordings. Presumably her outing on Universal was mentioned because the company was known to be in business at press time.

Five weeks later, Cash Box's Chicago tidbits included one about Dick Bradley of Tower Records having recorded Gloria Van and offering various people a "prevue" of the "disking" (November 19, 1949, p. 10). Strangely, there was no further mention till February 1950, when Cash Box (again?) had her cutting her first session with Tower. The only other information on offer was that Bill Snyder's orchestra, which had been in the show at the College Inn, had provided backing (February 11, 1950, p. 9). Tower 1473, by Bill Snyder with a different vocalist, was released that month. Had Tower recorded her (the first time) with a bandleader who was under contract to another company? It's hard to say, as the trades' coverage of Tower was frequently confusing.

And is there any chance that Tower recorded "The Gentleman Is a Dope," which had been Van's big number in the Rodgers and Hammerstein show? We don't know of any Gloria Van releases on Tower, either from 1949 or from 1950. And if she'd been inked to a year with the company, wouldn't she have stayed with it? We seriously doubt that Life lured her away with more money up front. In the end, Tower, despite its promotion in the trade papers, didn't really have much better distribution than Life did, Life would actually outlive its more widely known competitor by several months.

Johnny Sippel reviewed Gloria Van in another show, at Chez Paree in Chicago on February 13, 1950:

Despite poor attention, the supporting cast is above par. Gloria Van, Jane Russellish chirp, is developing an excellent torch style. Gal just inked with Life Records. Her interpretation of Love for Sale is a classic and netted a good mitt. Had she worked on a raised podium more people could have seen her and it would have cut the din. (Billboard, February 25, 1950, p. 46)

The headliner was Jimmy Durante, who drew a big, noisy crowd. The show opened on February 10; Van's appearance had been promoted in another brief item in Cash Box (February 4, 1950, p. 9). According to a Chez Paree 20th anniversary section in Billboard for December 8, 1952 (p. 22), the show closed on March 16.

Gloria Van (voc); Russ Grilley (voc -1); The Velvetones: Ernie Inucci (g); others unidentified.

Chicago, c. February 1950

| Bamboo | Life L-A-1002 | ||

| Knock, Knock, Knock -1 | Life L-B-1002 |

The ad, which appeared in the March 4, 1950 jukebox supplement to Billboard, does inform us about the company's distribution network. The Velvetones were a small combo, unconnected with the Velvetones from the East Coast who had recorded for Sonora in 1946-1947. In January 1951, the Chicago Velvetones were an accordion-guitar-bass trio; the guitarist, Ernie Inucci, was said to have done recording work with Gloria Van (and with Lee Monti's Tu-Tones). The other two members, who at the time (Southtown Economist, January 31, 1951, p. 11) were Al Rhomba (accordion) and Art Cavalieri (bass), may have arrived after this session.

The Billboard reviewers (March 18, 1950, p. 31) did not care for Life 1002. They considered "Bamboo" unimaginatively arranged and performed, and thought "Knock, Knock, Knock" was dopey (all four gave that side a 40 out of 100—though this was a rating seldom hung even on offerings from puny companies with no distribution, it was an improvement on Singing Tom's scores.) Life, like many other small labels then operating, put singers like Van at a disadvantage because the company didn't want to have to pay another music publisher royalties on a standard (besides "Love for Sale," she was known for her rendition of "Embraceable You"). The tunes she put on record for Master and VRT, as well as for Life, were the work of composers with ties to the company. Even so, her VRT single (which we have now heard) was pretty good. A couple of her other early records might also have been better than Life 1002.

In April, Life announced that it had picked up distributors in Berkeley, California, and San Francisco. "Max Miller's jazz combo and John Wyskowski's Omaha polka band have been added to Life's talent roster" (Billboard, April 8, 1950, p. 20). Although he was not mentioned, it appears that Paul Eduard Miller had once again helped to bring Max Miller together with a small record company.

Max Miller was now a Life artist, but his first release for the company was a reissue—of his only previously released recording as a leader. In fact, it is the only reissue on a single of anything that the short-lived Gold Seal put out. We were alerted to it by Larry Grinnell (email communications, November 8-9, 2012).

Max Miller (p); Andy Nelson (g); Buddy Nichols (b).

Myron Bachman Studio, Chicago, August 1946

| 6 | Heartbeat [Heartbeat Blues*] (Miller) | Gold Seal 401, Life L-B-1003* | |

| 7 | Caravan (Ellington-Tizol) | Gold Seal 401, Life L-A-1003 |

The Life reissue appeared in June 1950. It actually got a review in Billboard (July 8, 1950, p. 111) with ratings around 70 (these were good for a tiny label).

We have yet to find evidence of Life obtaining or using any of the remaining, unissued titles that Miller originally recorded for Green Records. In a 1982 letter, John Steiner claimed to have in his possession everything recorded for Green that had not been dealt to Gold Seal.

Three Jays: vocalists and instrumentalists unidentified.

Chicago, c. June 1950

| Save the Wishbone for Me Ma (Valli) | Life L-A-1004 | ||

| Penthouse Serenade (Jason Burton) | Life L-B-1004 |

A copy of this single, the last pop vocal item on Life that we know of, was in the collection of Bill Sabis. Otherwise, we know only that that it was released at the beginning of July 1950 (it was announced in Billboard on July 8, p. 38). It sports a black label with silver print. In this case, the company was willing to pay composer and publisher royalties on a standard. If only it had been willing to do the same on its Gloria Van session…

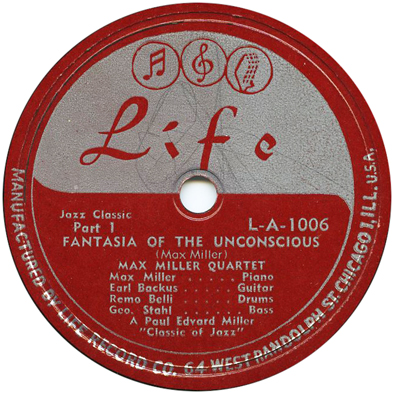

With the next four Max Miller sides, we are on firmer ground.

Max Miller's music was once again being promoted (in fact, his recording session was paid for) by his friend Paul Eduard Miller. The critic's endorsement was right there on the labels. Effects on sales are unknown and unproven.

On June 24, 1950, Billboard tersely announced in its Chicago items that "Max Miller has been made musical director for Life diskery. He cut eight sides last week" (p, 19). We know of four sides from the session. Were there four more?

Max Miller (p); Earl Backus (eg); George Stahl (b); Remo Belli (d).

Modern Recording Studio, Chicago, c. June 17, 1950

| MRS 2538-1 | Sunny Disposition (Miller) | Life L-B-1005 | |

| MRS 2538-2 | Jump for Al Benson | Lumbar Ganglion Jump (Miller) | Life L-A-1005 | |

| MRS-2538-3 | Fantasia of the Unconscious Part 1 (Miller) | Life L-A-1006 | |

| MRS-2538-4 | Fantasia of the Unconscious Part 2 (Miller) | Life L-B-1006 |

The personnel is supplied on the labels to Life 1005 and 1006. The matrix numbers from Edwin M. Webb's Modern Recording Studio, in those days a favorite venue for small record companies in Chicago, are incised in the trail-off area on each side. These come later in the MRS series than the Mildred Richardson session for JOB. They are just a little earlier than the first sides for Seymour, so they can be pretty confidently dated to July or August 1950.

We are indebted to Bob Sunenblick for details about a copy of Life 1006 in his collection. The same endorsement from Paul Eduard Miller appears at the bottom of the labels as on 1005.

"Fantasia of the Unconscious" is a remake of the same piece that Miller had cut for Green Records in 1946. Whether the first version was as long as this second one, we of course don't know. In the meantime, Miller had written out a different version of the piece for Howard Legere, a classical pianist, who featured it at some of his recitals.

In July, Life acquired a connection with Gary, Indiana, when it "inked Bud Pressner's 12-piece territory ork"; the company also added a Los Angeles-based manager for sales in the Western states (Billboard, July 15, 1950, p. 14).

Life actually sprang for a display ad in Billboard, on August 5, 1950 (p. 28). It mentioned the office in Los Angeles—and three Max Miller singles: Life 1003, 1005, and 1006.

We know of four further 78 rpm releases on Life 1011, 1012, 1013, and 1014. They were the counterparts of four 45 rpm releases, Life 5001 though 5005 (see below). Which may or may not imply the existence of a Life 1007, 1008, 1009, or 1010. Collectors, what say you?

On August 18, 1950, Max Miller's quartet opened the New Apex Club, 449 North Clark Street at Illinois Avenue. As of early October, it featured Denny Roche, trumpet, and Frank Gassi, guitar, along with a drummer.

But Miller then took a brief hiatus from the label. According a brief Chicago item in the September 9 issue of Billboard, "Max Miller, musical director of Life Records here, will cut an eight-selection LP for Columbia" (p. 21). George Avakian was in the midst of producing a series of 10-inch LPs called Piano Moods; Miller was recommended to him by a local distributor.

The series put Max Miller in good company. The first LP to be released was by Erroll Garner; the other jazz contributors were Ralph Sutton, Jess Stacy, Joe Bushkin, Teddy Wilson, Eddie Heywood, Stan Freeman, Buddy Weed, Bill Clifton, and Earl Hines.

Columbia wasn't doing a whole lot of recording in Chicago in 1950. The Melrose combine had wrapped up its blues operations with the company, and the OKeh subsidiary wouldn't be revived for another year. CCO items were being recorded at the rate of 8 per month, on average. They wouldn't pick up the pace even after OKeh reopened.

Avakian wanted each side of the Piano Moods LPs to proceed without pauses between tracks, and the pianists obliged with transitional passages to bridge to the next piece. Consequently, the tracks from Miller's Columbia session are listed in the order of their appearance on the LP instead of the order in which they were recorded (the latter may easily be inferred from the matrix numbers).

Max Miller (p); Earl Backus (g); Bill Holyoke (b); Remo Belli (d).

Chicago, September 28, 1950

| CCO 5189-1 | St. Louis Blues (Handy) | Columbia CL 6175, Columbia 39338*, Columbia 4-39338, Mosaic MD7-199 [CD] | |

| CCO 5196 | Liebestraum [No. 3] (Liszt) | Columbia CL 6175, Columbia 39339, Columbia 4-39339, Mosaic MD7-199 [CD] | |

| CCO 5190 | Don't Blame Me (Fields-McHugh) | Columbia CL 6175, Columbia 39339, Columbia 4-39339, Mosaic MD7-199 [CD] | |

| CCO 5191-1 | Lover (Rodgers-Hart) | Columbia CL 6175, Columbia 39338*, Columbia 4-39338, Mosaic MD7-199 [CD] | |

| CCO 5192 | Rose Room (Wiliams-Hickman) | Columbia CL 6175, Columbia 39340, Columbia 4-39340, Mosaic MD7-199 [CD] | |

| CCO 5195 | Besame Mucho (Velazquez) | Columbia CL 6175, Columbia 39341, Columbia 4-39341, Mosaic MD7-199 [CD] | |

| CCO 5193 | Embraceable You (Gershwin-Gershwin) | Columbia CL 6175, Columbia 39341, Columbia 4-39341, Mosaic MD7-199 [CD] | |

| CCO 5194 | I Can't Believe That You're in Love with Me | Columbia CL 6175, Columbia 39340, Columbia 4-39340, Mosaic MD7-199 [CD] |

The 10-inch LP, Columbia CL 6175, was released on July 13, 1951. It was the last jazz offering in the Piano Moods series. It is the only Max Miller recording that most have heard of, and the only one to be listed in Tom Lord's Jazz Discography. On August 4, 1951 (p. 7), Cash Box mentioned Columbia 39338, "Lover" and "St. Louis Blues," as though Miller had just recorded those two sides.

Columbia also released the other 6 sides on singles, both 78 and 45 rpm. The 45s carry the 4- prefix. Interestingly, the DJ copies we have seen of 39338 don't show a release number; they merely carry the matrix numbers and refer to Miller's "Columbia set."

In 2000, all of the 10-inch LP sessions by jazz pianists for the Piano Moods series, along with Ahmad Jamal's first two sessions for OKeh, a second Ralph Sutton LP, and a live concert by Art Tatum, were compiled into Mosaic MD7-199, a 7-CD set titled The Columbia Jazz Piano Moods Sessions. The matrix numbers, original track order, and release numbers for the singles were all obtained from the Mosaic booklet.

The Mosaic set is the only reissue that most items in the Piano Moods series have gotten, and its production quality meets Mosaic's usual high standards. However, the liner notes by Dick Katz presume that the reader knows the life stories of Art Tatum, Earl Hines, Erroll Garner, and Teddy Wilson, and supply less than adequate detail about the less famous contributors. Max Miller is incorrectly said to have been born in 1915 and none of his other recordings are mentioned. Katz also says that Miller derived much of his income from work on recording sessions. That is a claim we are inclined to doubt, and have not seen made anywhere else.

Although we have yet to document a Life release from 1951, the company was still making recordings—at its customary desultory pace. Bud Pressner's territory band, based in Gary, Indiana, recorded for Life in the first week of June, according to a Billboard Chicago item on p. 14 of the June 16 edition. We would like to see one of Pressner's records. There's room between Life 1007 and 1010 for something of his.

In May and June 1951, Max Miller was at the Hi-Note again, with Denny Roche, trumpet; Earl Backus, guitar; and Buddy Nichols, bass—and Anita O'Day, vocals. He was even getting an occasional blurb in the trades: "Party for Max Miller, great jazz pianist, at the Seven Stairs this past Thursday, crowded" (Cash Box, July 7, 1951, p. 7; the event was probably on June 29). This had more to do with Miller's work around Chicago and with the imminent release of his Columbia LP than with anything he was doing or had been doing for Life. In September 1951, when the Milwaukee Journal ran a piece on him, he was working in that city with a trio.

In 1952, Life tried kicking things up a notch. A Billboard article about some movements in record distrbution in Chicago ("Chi Distrib Changes in R&B Field," March 1, 1952, p. 35; story dated February 23) treated Life as a new pickup for Art Sheridan's American Record Distibutors (which it wasn't; the article also presented Sheridan's own Chance label as a new operation, which it wasn't). In the process, it misspelled the name of Life's owner. (However, some other coverage from 1952 identified "R. Maloney" as an owner or part-owner, so perhaps W. W. had bowed out in favor of another family member.) The article did indicate that Life "is readying a more aggressive cutting and selling campaign."

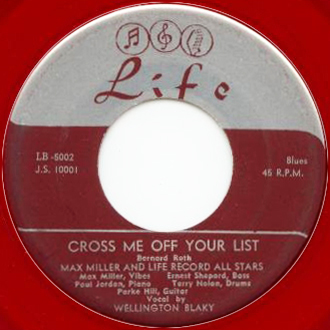

Max Miller had probably just cut one more session for Life, which launched a new 5000 series for its 45s. This time Paul Eduard Miller was not mentioned on the labels and presumably was not having to pay for anything. Two of the four sides featured a singer from Gary, Indiana named Wellington Blakey, singing songs written by a butcher, also from Gary, Indiana, named Bernard Roth. (We strongly suspect Bud Pressner had brought both Roth and Blakey to the company's attention.) The other two sides were instrumental renditions of jazz standards. Miller, who was operating his own studio by this time, played vibes throughout.

We once thought Life might have given up on 78s during this phase, but we now have confirmation of all four releases on 78 rpm: 1011 (in the collection of Bob Sunenblick), 1012 (listed as a new release in Billboard), and 1013 and 1014 (in the collection of Robert L. Campbell).

Max Miller (vib); Parke Hill (eg); Paul Jordan (p on %); Ernest Shepard (b); Terry Nolan (d on %); Wellington Blakey (voc on %).

Max Miller's studio, Chicago, February 1952

| KB 1690 | Jazz Me Blues (Deloney) | Life A-1011, Life A-5001 | |

| Tea for Two (Youmans-Caesar) | Life A-1012, Life A-5002 | ||

| KB 1698 | Only You (Roth) % | Life B-1011, Life B-5001 | |

| Cross Me off Your List (Roth) % | Life B-1012, Life B-5002 |

We learned of Life 1011, the 78-rpm release, from Bob Sunenblick. The label copy is virtually identical to what can be seen on Life 5001. For instance, Wellington Blakey's name is misspelled (the same way) on both B-sides. Instead of the JS numbers that can be seen on Life 5001, the 1011 labels carry N. S. 5003 on both sides. Also, the 78 carries the KB 1600 series numbers in the trail-off vinyl. These do not come from any known commercial recording operation in Chicago during the period; we strongly suspect they were from Miller's own studio. The 78 labels leave off the composer credit for "Jazz Me Blues" that we can see on the 45 labels.

The 78s and 45s from this session were released in March 1952. Billboard, which received and reviewed them on 78 rpm, listed 1011 and 1012 as new releases on March 22 (p. 45) and reviewed Life 1011 on March 29, 1952 (p. 85).

Max Miller must have felt he was on a roll in February and March 1952. He had two new records out, and there was a TV special starring Benny Goodman. For the occasion, a band was assembled by Freddy Williamson, who worked in the Chicago office of prominent agent Joe Glaser. It included Red Saunders at the drums and Max Miller on vibes (Sam Evans, "Kickin' the Blues Around," Cash Box, March 1, 1952, p. 16).

We should note that a second Life label was active during the same period, and that it got more mentions in Billboard, for what that might be worth. The "other" Life was in New York City. It was already up and running in 1948 (see Billboard, NAMM section, June 19, 1948, p. 58), was still going in 1952, and had nothing to do with the Chicago operation.

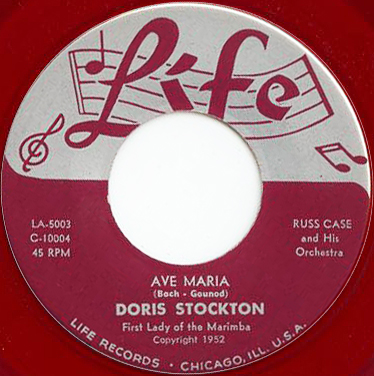

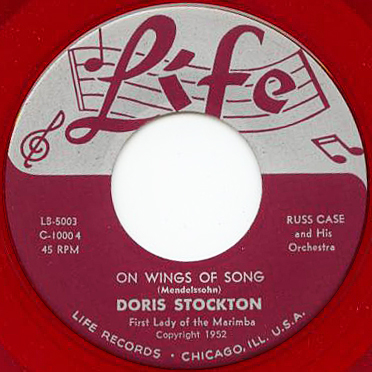

The final two releases on the Chicago Life, also from 1952, featured Doris Stockton playing "Tico Tico" and three light classics on the marimba. Accompaniment on these was by studio bands led by Russ Case. Born around 1916, Stockton did little commercial recording beyond the one session, originally for RCA Victor, that Life made a deal to reissue. She was recorded on other occasions, and kept copies, but those we have seen were lacquers cut at concerts or taken off radio broadcasts; when there are dates, they are from the late 1940s.

Like their counterparts on 78 rpm, Life 5003 and 5004 feature a new, less busy version of the company logo. In addition, the copies of Life 5004 that we have seen were pressed on unusual lemon-yellow vinyl; Life 5003 was pressed on red vinyl.

Life had arranged to reissue 1947 sides that Stockton had made for RCA Victor:

Life Records has completed a royalty deal with RCA Victor and will issue a series of eight sides cut in 1947 by Russ Case and Doris Stockon on its own label. R. Maloney, Life topper, said the eight classics will be released on 45, 78 r.p.m, and LP. (Billboard, March 1, 1952, p. 40)

Eight tracks was just right for a regulation 10-inch LP, but we haven't seen any on Life. We know of two 78s in the 1000 series (not easy to find; we learned about them from Arthur DeBolt after Doris Stockton's death). And we know of the same two releases (a little easier to get in this form) on 45s in the 5000 series. Life seems to have made it through half of the projected eight sides. Three of the sides reissued on Life employed orchestral arrangements including strings; "Tico Tico" used a Swing band.

Doris Stockton (mar); Russ Case (dir); other musicians unidentified.

January or February 1947

| D7VB-222 [RCA Victor 78 only] | Ave Maria (Bach-Gounod) | RCA Victor 20-3102B, Life LA-1013, Life A-5003 | |

| D7VB-220 D7VW-0220 |

On Wings of Song (Mendelssohn) | RCA Victor 20-3104B, Life LB-1013, Life B-5003 | |

| D7VB-216 D7VW-0216 |

Tico Tico (Drake-Abreu) | RCA Victor 20-3104A, Life LA-1014, Life A-5004 | |

| D7VB-218 D7VW-0218 |

F. Major Waltz (Chopin) | RCA Victor 20-3105B, Life LB-1014, Life B-5004 |

From release numbers stamped in the trailoff area of three of the four Life 78s sides, we see that "Tico Tico" and "On Wings of Song" were originally paired on RCA Victor 20-3104. "F. Major Waltz" was originally RCA Victor 20-3105B. "Ave Maria" was probably remastered for its Life release, because it carries no RCA Victor release number; according to Tyrone Settlemier's listing at http://www.78discography.com/RCA203000.htm it had been on 20-3102. In an ad featuring new releases, RCA Victor mentioned a four-pocket album, Marimba Classics, on September 25, 1948 (Cash Box, p. 7). The album number was P-222 and the indidvidual 78s were 20-3102 through 20-3105. "Ave Maria" is listed there as the B side of 20-3102.

The sides not reissed on Life were: RCA Victor 20-3102A, "Perpetual Motion"; RCA Victor 20-3103A, "Waltz of the Flowers" and B, "Hora Staccato"; and 20-3105A, "The Swan."

The D7VB numbers are the original matrix numbers for the 78s; the D7VW numbers were modified by RCA Victor using its standard code for 45 rpm masters (there wouldn't have been any of these in 1947). Judging from other RCA Victor releases with known D7VB numbers, the recording session took place in January or February 1947. There is no clue to the location, which could have been New York, Chicago, or Los Angeles.

So far as we know, 1014/5004 was the label's last release.

Life's burst of activity lasted three or four months. By July 1952, it appeared from some new friendly mentions in Cash Box (which had not carried ads for the company's 1952 releases, or reviewed them) that R. Maloney and whoever else had a piece of the operation had given up on commercial distribution for their four new singles. According to Sam Evans' column for July 5, 1952, there was a new company called Life, Max Miller "headed" it, and, by implication, Life 5001 and 5002 were its first releases (Cash Box, p. 13). At least Evans spelled Wellington Blakey's name correctly. Subsequent mentions proclaimed that "Max Miller, star of the 88's, is now also a disk distrib. For [sic] 'Life Records.' (Cash Box, July 12, 1952, p. 7). Then Evans gave the company the same address as Miller's studio: "Life Record Co. in business at 222 West North Ave., Chicago. Waxery is headed by Max Miller, a real mean man with the vibes" (Cash Box, July 26, 1952, p. 15). Through the haze, we may faintly discern Max Miller selling the remaining stock of his own Life releases (and maybe what was left of the others) out of his studio.

Finally, in March 1953, Cash Box, in its regular notices for Chicago (still heavy, in those days, on the Mickey Mouse band bookings, including Ray Pearl's), declared that "Maloney, Mayer & Wise are the three who own Life label which is cutting Ted Reynolds, GI Sgt. who won Morris B. Sachs amateur hour contest and also appeared with Harvest Moon ball winners. Ray Pearl ork will background the boy" (March 14, 1953, p. 9). This was the company's last gasp; it would not be mentioned again in the trades. We have no idea what Sergeant Ted Reynolds sounded like, and there is no reason to suppose that any further recordings materialized.

In all, Life had been responsible for 10 singles: all 10 in the 1000 series for 78s and 4 in the 5000s for 45s. The known 78s are 1001 A and B (probably) and 1001 C and D (definitely) through 1006, and 1011 through 1014. Still missing are 1007 through 1010. The 45s were 5001 through 5004, and the company's last four releases appeared in both series.

We suspect Gloria Van completely forgot her single on Life Records. She was on a DuMont network TV show called "Windy City Jamboree" from April 1950 into the summer. The Down Beat scribes liked her, and in March 1951 they put her on the cover for the second time (in 1944, she had shared one with Hal McIntyre). In the first half of the 1950s, her bread and butter would be singing for sweet bands. In August 1950, Wayne King lost his regular female vocalist (Nancy Evans, who had been with him for more than 5 years, opened her own TV production office; Cash Box, August 19, 1950, p. 7). Gloria Van took over in September 1950, the beginning of King's second year on television; "music boys [were] still talking about that full hour opening show of Wayne King's with Gloria Van, Harry Hall, and his entire TV gang bringing down the house" (Cash Box, November 11, 1950, p. 11). She stayed with him for 2 full seasons of his NBC show (through June 1952). The TV work often entailed gigs in Chicago hotels (as in October 1950, when "Wayne King with his entire TV gang" were booked into the Edgewater; Cash Box, October 28, 1950, p. 9). The shtick usually required her to dress as a Native American or an Italian peasant girl.

This all being live TV, on one occasion Van was mortified when she started "Kiss of Fire" (a song that was charting in 1952) and realized she'd forgotten every word of the lyrics. "I just went blank, and here I was in this dumb window frame, and I couldn't even see the band to get any help," she told Christine Winter in 1990. "I finally just made the words up as I went along." King's show was a forerunner to Lawrence Welk's: the band was squarer than she would have liked, but the pay was good and she made friends. There was the further benefit that King broadcast the show 44 weeks each year, from Chicago, so out-of-town engagements were generally confined to Monday nights and not too far away. When his TV deal ended, King started touring, which was not in her plans. She appeared on a local Chicago TV show for a while, did the "Chance of a Lifetime" show in 1953, and spent some time in the Teddy Phillips band, which she left at the end of September 1954, while Phillips was a fixture at the Martinique (Billboard, October 2, 1954, p. 22). (Phillips was making records during this period, for a variety of labels, but in the studio he seems to have stayed with Lynn Hoyt as his female vocalist. We don't know of any Phillips sides that feature Gloria Van.)

She did get further opportunities to record. In 1950, Billboard mentioned a single for Tower, supoosedly with Buddy DiVito's band. The whole thing could have been a muddled reference to whatever she'd cut in October or November 1949. Then again, Buddy DiVito did record for Tower (as a singer, not as a bandleader) in 1950. Nothing of DiVito's saw release till December 1951, after Joe Bihari of Modern bought what was left of Tower (and soon lost interest in releasing more such material). The Tower items that we know got a delayed, limited release and featured either DiVito or Elaine Rodgers singing with the same band.

But after leaving Teddy Phillips, Gloria Van recorded four tunes, around the beginning of 1955, for Archie Levington of Studio Music (Levington was married to Fran Allison, Gloria's sister-in-law). The omnipresent Lew Douglas Orchestra backed her, along with a vocal group billed as the Vanguards (any connection with her late 1940s group is unlikely, though Lynn Allison could have participated). Levington dealt the sides to X, a new subsidiary of RCA Victor. The deal was announced in March (Cash Box, March 26, 1955, p. 17) and X-0111 was out in April (reviewed in Billboard on April 23, p. 52; talked up in Cash Box on the same date, p. 10). Van made a round of promotional appearances for X; for instance, she performed at a Rock-Ola exhibition in Chicago (Cash Box, May 7, 1955, p. 7) and sang at a juke box operators' convention in the Catskills (Billboard, June 18, 1955, p. 76). But when X passed on "Che Sara, Sara" and "I Wanna Be There," Levington got these two masters back and redealt them to Wing (a newly launched subsidiary of Mercury). On August 13, 1955, Cash Box mentioned (p. 13) that Gloria Van had recently been working at the Cairo Lounge, and (incorrectly) that she would be recording for Wing. Her contract with Wing was announced on August 27, 1955 ("Wing Signs 4 Artists; 2 in Pop, 2 R.&B.," Billboard, September 3, 1955, p. 15; "Wing Inks Two," Cash Box, August 27, 1955, p. 30) and the two sides as released on Wing 90019 were advertised in Billboard for September 3 (p. 37). Wing featured 90019 in a Cash Box ad for September 24 (p. 13). Wing must have picked up just the two, because by the end of the year she was with another company.

An outfit called Reserve, which was based in Cleveland, started up in December 1955. Gloria Van's signing was included in the launch announcement, with her first release planned for January 1956 ("Reserve Records Formed," Cash Box, December 24, 1955, p. 30). Reserve 103 carries G series matrix numbers from RCA Victor's custom pressing division, indicating that it was mastered and pressed in 1956. So does Reserve 106, which presumably appeared a little later. Reserve didn't employ a big studio ork. Gloria Van was backed by Earl Backus and Remo Biondi (guitars), Bob Acri (piano), and Al Poskonka (bass). Reserve kept going till some point in 1957, but without calling Gloria Van back into the studio.

After her Reserve singles, Gloria Van became a part-time performer. The demand for her style of singing was softening, her husband was running a music store, she had to cancel some engagements on account of being pregnant, and by 1963 she had three school-age children. She did some local TV work (for instance, on Channel 9's Dial 9 for Music, Chicago Sunday Tribune, August 19, 1956, pt. 3 radio). She also appeared on Arthur Godfrey's show in 1957, and on the Jack Paar edition of the Tonight Show in 1958. In 1960, she sang Hoagy Carmichael's "Stardust" with a 100-piece orchestra at Soldier Field, at the composer's request, in front of 75,000 people.

Gloria Van would get one more commercial recording. Norman 536, "Hear Me" (sung partly in Italian) and "Raindrops", came out in 1963 (Cash Box reviewed it on April 6, p. 16). With the repertoire she had developed over 25 years as a performer, Gloria Van would have benefited from an LP that let her work with some of her favorite standards, but no such opportunity arose.

In later years she worked as head receptionist for the Kemper Insurance Company and, after undergoing two heart operations, for a support group called Mended Hearts. Interviewed by the Chicago Tribune at age 70, she was still recording herself at home in Elk Grove Village, singing over band-minus-vocalist records. Lynn Allison died in 1993, not long after their 50th wedding annversary. She made one private-issue CD. Gloria Van gave her last public performance in September 2002, with Rick Falotta and the Yorkville community band. Lucille Fanolla Allison died of kidney failure on December 24, 2002, in Elk Grove Village, Illinois (see Christine Winter, "Singer Van Gets a Kick Reliving Her Gloria Days," Chicago Tribune, November 4, 1990, http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1990-11-04/news/9004010313_1_air-force-band-congress-hotel-big-band; Archibald McKinlay, "Calumet Roots: Big Band 's Heyday Gave Singer Fame," Shia Kapos, "Gloria Van, 82: Jazz singer, TV star during the '40s, '50s," The Northwest Indiana Times, January 9, 1999, http://www.nwitimes.com/uncategorized/big-band-s-heyday-gave-singer-fame/article_88c6a1ec-b5e3-52fe-a8db-ac5083d2a002.html, and Chicago Tribune, December 26, 2002, http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2002-12-26/news/0212260018_1_big-band-singer-gene-krupa-variety-show; Joe Carlton, "Interview with the Crew Chief," The Great Escape! No. 17 (January/February 2010), pp. 1, 4, http://www.dixieswing.com/vol17.pdf).

Doris Stockton continued to perform for many years, eventually moving to California. In 2009, now 93 years old, she donated her instrument to a university. Doris Stockton died on March 7, 2013, at the age of 97 (our thanks to Arthur DeBolt for the news).

In September 1953, Wellington Blakey cut one of the very first sessions for Vee-Jay, which in its formative stage was located in Gary, Indiana. His Vee-Jay single also featured two songs writtten by Bernard Roth. Blakey seems to have stayed in Gary, which limited his recording opportunities. In 1960, Bud Pressner's studio made a 78-rpm acetate out of 4 of Blakey's live performances, powerfully sung but recorded in a club on really cheap equipment; obviously it was meant as a demo. In 1964, he was invited to sing the blues on a Riverside LP being recorded by his cousin's band; "Wellington's Blues" would be his only recorded performance with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers.

Bernard Roth continued to peddle songs to Vee-Jay; he was responsible for at least 3 numbers recorded by the doowop group, The Spaniels. At some point he obtained an introduction to Leonard Chess, submitting a few blues tunes that were recorded by Little Walter ("Who") and Muddy Waters ("Just to Be with You," "40 Days and 40 Nights"). Among Roth's songs, the two that he wrote for Muddy benefited from absolutely blazing performances at two sessions in 1956 and have become by far the best known of anything he did.

Max Miller kept up a high level of activity on the Chicago club scene for several more years. In 1953, his column "The Audio Workshop" ran in Down Beat, netting him free equipment from some of the top audio manufacturers of the day. He recorded frequently in his studio, also venturing out to make live jazz recordings in a variety of locations. He also kept an even greater distance from the commercial recording industry, and bought his way out of a contract with a major management agency, MCA, after learning that MCA would end up owning rights to any original compositions that he recorded.

On July 20, 1955, he opened a club called Max Miller's Scene, at 2126 North Clark Street. At first, he fulfilled nearly all of the musical duties, playing piano with a trio. On May 10, 1956, the Defender announced (p. 18) that singer Phyllis Branch, previously known as a calypso perfomer, was moving into the Scene, along with pianist Earma Thompson (enabling Miller to concentrate on playing the vibes). In time Miller discovered, like others before him, that operating a club and performing at it five nights a week didn't mix. An item in the Defender for September 25, 1956 (p. 15) announced that the Jazz Scene, as it was now known, would be under new management as of September 26; the new house trio consisted of Gene Esposito (piano), LeRoy Jackson (bass), and visiting Ghanaian drummer Guy Warren. The club closed in 1957.

In 1958, Miller landed a couple of gigs at the Golden Lion Inn, in the Sheridan Plaza Hotel. On September 12, 1958, he began an engagement at the inn with violinist Eddie South (Defender, September 10, 1958, p. 17). When that gig ended in early November, Miller moved out quickly, leaving behind a bill for repairs to the apartment where he had been staying (it was owned by John Steiner, who kept the invoices). After several months living on a farm in Missouri, Miller returned to Chicago for a job at the London House (Wacker at Michigan Avenue), where he was recorded backing trumpeter Bobby Hackett.

Bobby Hackett (tp except -1); Max Miller (p); Bill Cronk (b); Buzzy Drootin (d).

London House, Chicago, between June 2 and June 21, 1959

| St. Louis Blues (Handy) | Mr. Music MMCD-7019 | ||

| When Your Lover Has Gone (Swan) | Mr. Music MMCD-7019 | ||

| Muskrat [sic] Ramble (Ory) | Mr. Music MMCD-7019 | ||

| Caravan (Tizol-Ellington-Mills) -1 | Mr. Music MMCD-7019 | ||

| Tenderly (Gross-Lawrence) | Mr. Music MMCD-7019 | ||

| Bernies [sic] Tune (Miller) | Mr. Music MMCD-7019 | ||

| Take the A Train (Strayhorn) | Mr. Music MMCD-7019 | ||

| Indiana (Hanley) | Mr. Music MMCD-7019 | ||

| Limehouse Blues (Braham-Furber) | Mr. Music MMCD-7019 | ||

| These Foolish Things (Strachey) | Mr. Music MMCD-7019 | ||

| Caravan #2 (Tizol-Ellington-Mills) -1 | Mr. Music MMCD-7019 | ||

| Rose Room (Williams-Hickman) | Mr. Music MMCD-7019 | ||

| Struttin' with Some Barbecue (Armstrong) | Mr. Music MMCD-7019 | ||

| Sweet Lorraine (Parish-Burwell) | Mr. Music MMCD-7019 | ||

| Take the A Train #2 (Strayhorn) | Mr. Music MMCD-7019 |

The Armed Forces Recording Service recorded Bobby Hackett's group live on several occasions during their three-week run at the London House. These were edited down into two 30-minute broadcasts, with voiceovers by two different announcers added, for the AFRS One Night Stand series. (The announcer on the first 8 tracks tries to be cute with song titles, then partly redeems himself by employing the original, unbowdlerized "Muskat Ramble.") Each broadcast was distributed on 16-inch transcription disks. The first eight tracks appeared on One Night Stand 4918, broadcast on September 25, 1959; the final 7 were on One Night Stand 4933, broadcast on October 16 of the same year. It is not known on which nights the selections were recorded, but two different performances of "Caravan" and "Take the 'A' Train" were included. Personnel and other information are derived from the 2009 release on Mr. Music MMCD-7019.

The Bobby Hackett broadcasts, which were done in decent sound, allow us to hear Max Miller as an accompanist. He was given a nightly feature on "Caravan." On both 1959 performances, he follows his 1946 arrangement quite closely.

The London House gig was the very last in Chicago. Miller hit the road, spending time in Dallas, Texas, Tucson, Arizona, and Miami, Florida. By 1965 he had settled in Oklahoma, where he taught and performed, health permitting. As of 1982, when he resumed his correspondence with John Steiner, any damage to Steiner's apartment was long forgiven; Steiner wrote a letter in support of an application for a grant to get Miller's lacquers, tapes, and scores in order, but the application was not successful. On June 18, 1985, just a few months before his death, he was interviewed by jazz writer John Chilton for a book on Sidney Bechet. Max Miller died in Shawnee, Oklahoma on November 13, 1985, of congestive heart failure. After his death, his third wife, Juanita Strange Miller, catalogued his compositions and recordings; she died in 1995.

An introduction to Max Miller's life and music can be had from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max_Miller_(musician).

Click here to return to Red Saunders Research Foundation page.