Revision note. We have news from Paul Solarski (email of December 6, 2022) about a previously unknown single by the Bob Perkins Trio, made for a small label out of Hammond, Indiana. It was made a year and a half (or more) after the trio's single on Planet. Bob Perkins now has two singles to his name.

Chicago's postwar recording boom produced a number of remarkable blues recordings by small boutique recording companies. Among these were Planet (with just three known releases) and Marvel (with just two). Planet and Marvel helped pioneer an electrified country blues style by releasing the first-ever recordings by Snooky and Moody, Johnny Young, and Floyd Jones, all three acts becoming Chicago blues legends. The labels also came out with a Jimmy McCracklin record, picked up from the West Coast label Trilon, and a jazz combo release by the Bob Perkins Trio. Planet and Marvel 78s are exceedingly rare today, because in a fairly short time—most likely a few weeks—the records were picked up by Old Swing-Master, a larger operation established by Egmont Sonderling and deejay Al Benson.

The person who produced most of the Planet and Marvel recordings was an entrepreneur named Chester A. Scales (1914-1997) who owned a small record store on the Near North Side of Chicago. Up to now he has been little more than a name to blues researchers, and his exact association with these two labels has been left indeterminate. The following account is based in part on an interview with Scales’ stepson, Charles Bishop, who was a teenager at the time of these recordings. Bishop’s account has helped us to put together a story of Scales’s career and fill in a few blanks, but his precise relationship with Planet and Marvel is still conjectural.

Chester A. Scales was born November 20, 1914 in Mississippi. (We wonder whether the A. stood for "Arthur"—that would give Scales something in common with Howlin' Wolf.) He spent his childhood in Kansas City, Kansas, but by his teenage years had moved to St. Louis, where he attended Washington Technical High School. Chester Scales met Clara Ellison in St. Louis in 1936. (Ellison was born in Jackson, Tennessee, and had given birth to Charles Bishop in 1930.) Roughly from 1936 to 1939, Chester and Clara together operated the Rosebud Club on the famous African-American nightclub strip on Delmar (at Leffingwell Street). By the time they were married in December 1939, they were operating Clara’s Furniture Shop, and were no longer in the nightclub business.

In 1942, Chester Scales was jailed on a bigamy conviction, and Clara moved to Chicago. Scales got out of jail in 1943, reconciled with Clara and joined her in Chicago. By the end of World War II they were running a small record store on the Near North Side.

During the summers, Bishop would visit his mother and Scales in Chicago. A second family was developing there. After Clara miscarried with twins, Chester (in Bishop’s words) "decided to make kids on the outside." With two different other women, he had a girl, Evette, and a boy, Chester Jr. He met Evette’s mother in Maxwell Street, the outdoor flea market on the city’s West Side, where bluesmen would busk for change. Bishop recalls his stepfather as being very popular with the ladies, a 6-foot-tall imposing figure.

The Scales family lived on the Near North Side of the city, on Orleans Avenue. Bishop remembers John Lee Williamson (the first Sonny Boy) as well as Tampa Red and other blues artists dropping by Scales’s home. Williamson was an old friend of Clara. While Clara was in her first year of high school in Jackson, Tennessee, she and a friend, Parka Bennett, became friends with Williamson, who was 18 to 21 at the time. Family lore has it that the bluesman wrote "Good Morning Little School Girl" for Parka Bennett, with whom he was smitten. That was in the early 1930s; Williamson had his hit with the song in 1937.

A few blocks from the home, at 941 North Sedgwick, Chester and Clara operated the Northside Playland and Record Shop. The shop was right in the midst of a small African-American community, at the intersection of Sedgwick and Division, with several clubs nearby, notably the Square Deal at 230 West Division. Also at the intersection was the Oscar Mayer sausage factory, where several of the local bluesmen worked, including guitarist Johnny Williams, who accompanied Johnny Young on his early records.

Every Sunday morning, during the summer, Bishop would accompany his stepfather to Maxwell Street and set up shop on the street with records and radios from the store. The outdoor operation took electricity from the park behind them. Bishop mistakenly, but understandably, believed it was at the Maxwell Street market that Scales discovered Snooky and Moody and his other recording acts, Man Young and Floyd Jones. All of these musicians worked the outdoor market during the late 1940s.

When interviewed by Blues Unlimited in 1980, Snooky Pryor said that Scales actually discovered him on the Near North Side—first while playing outside his store with a guitarist named Grey Haired Bill [Johnson], and then playing with Moody Jones and Floyd Jones in a nearby club on Sedgwick. The recording was done with just Moody Jones, because at the time of the session Floyd Jones could not be found. As far as his recording contract went, Pryor said, "[Scales] pitched up a big deal and everything, and me not knowing too much about the recording business, I told the guy OK. So he set up a date and told me he was setting up on his own label. But then Al Benson wind up having the record and master and everything. I got paid for the session, but royalties, that was out. Scales was a real genius, if you know what I’m talking about, pretty slick. Yeah he was my peoples (laughs), but the guy he was real slick, he really knew his business." Being a neophyte in the business himself, Pryor probably had an exaggerated sense of how significant a figure Scales was, but he recalled that "he really was known and he knew all about the record business and about distributors."

One might surmise from Snooky’s recollections that Scales released Snooky and Moody on his own Planet imprint and then leased the record to Old Swing-Master, which was owned by Egmont Sonderling and A&R’d by deejay Al Benson (who secretly had a piece of the company). Bishop remembers that Scales had a warehouse at Orleans and Hubbard, and says he set up his record operation there. Bishop then suggests that white guys "took the label away" from Scales, which in his imperfect memory seems to indicate the transfer from Planet to Old Swing-Master—a label majority owned by Sonderling. Pryor’s reference to Scales’s slickness undoubtedly stems from his greater worldliness in the record business. As we will see below, Scales certainly knew enough about the business to list himself as the composer of two Floyd Jones tunes.

James Edward "Snooky" Pryor (voc, hca); Moody Jones (eg).

Chicago, November or December 1948

| PL 101 | Telephone Blues | Planet 101/102, Old Swing-Master 18A, Flyright LP 100, Magpie LP 1813, Flyright CD 20, Paula PCD-11 [CD], Indigo IGOCD 2095, Westside WESA 869 [CD] | |

| PL 102 | Boogie | Planet 101/102, Old Swing-Master 18B, Flyright LP 100, Magpie LP 1813, Flyright CD 20, Paula PCD-11, Charly CDGR 143-2, Indigo IGOCD 2095, Westside WESA 869 [CD] |

Some copies of Planet 101/102 have a plain label, like the one pictured here. The matrix numbers are the release number. In the wax on each side there is also a monogram that looks like an MP tied together. Other copies are extant with a Saturn logo that has "Planet for platters" written across the rings; we assume these came out a little later. (See the cover of Blues Unlimited, 137/138 (1980) for a photo of the PL 101 side of one of these.)

The Flyright (1969) and Magpie (1986) LPs, each issued as Snooky Pryor, are identical and both originated from the UK. The CDs on Flyright (UK) and Paula (USA) are identical and again released as by Snooky Pryor (1991). The Charly CD was issued as Chicago Blues: The Golden Era (1997), the Indigo CD was called Chicago Blues Hard Times (1999), and the Westside CD was called Pitch a Boogie Woogie If It Takes Me All Night Long—Seminal Post-War Chicago Blues (2001). This last was billed as by Snooky Pryor and Friends.

James Edward "Snooky" Pryor was born on September 15, 1921, in Lambert, Mississippi. His style on the harmonica was derived in roughly equal parts from John Lee "Sonny Boy" Williamson and Aleck Miller (aka Sonny Boy Williamson #2). He got the idea of amplifying his harmonica while serving in the military during World War II, and in 1945 began performing at the Maxwell Street market with portable PA system he purchased at a store at 504 South State. As the first to amplify a harmonica, Pryor should rightly be recognized as a blues pioneer. As he boasted to Living Blues, "I started the big noise around Chicago."

The sides that he made for Planet and Marvel were his first recordings. A Billboard review in May 1949 covered Old Swing-Master's reissue of Snooky & Moody's "Telephone Blues" and "Boogie." It was typically negative ("not especially inspired"), yet today the record is seen as a classic of postwar Chicago blues. Mike Rowe said of the two sides, "It is the lilting swing imparted by Moody's guitar that makes the record sound so modern for the time. Equally rhythmic is Snooky's singing and the interplay of the voice, harmonica, and guitar is particularly exciting."

"Boogie" is a spirited number, which swings with verve, and Pryor with his piercingly sharp harp sound blows with élan. Moody moves the number along with a robust boogie beat. The number is mostly instrumental, but Pryor talks the lyrics in places, opening with a reference to his neighborhood:

One dayThis monologue is too close in shape and rhythm to John Lee Hooker’s world-famous recitation about Hastings Street and Henry’s Swing Club to be a coincidence, though Moody Jones makes no attempt to emulate Hooker’s attack on the guitar. Since Hooker’s "Boogie Chillen" was released in November 1948, we can date this session with some confidence to November or December of that year.

Snooky Pryor subsequently recorded as a sideman for Sunnyland Slim's Sunny label (1950), and as a leader for JOB (1950, 1952, 1954), Parrot (1954), and Vee-Jay (1956). He retired from music in 1962 after one last session with JOB. In 1971 Living Blues magazine lured him out of retirement, and conducted the first published interview with him. He recorded an LP for Bluesway in 1973 (Do It If You Want), but did not become a hit on the blues revival circuit until a Blind Pig release in 1987 (Snooky). He continued to record into the 1990s for such labels as Antone’s and Discovery. Snooky Pryor died on October 18, 2006, in South East Missouri Hospital in Cape Girardeau. He was 85 years old.

Snooky Pryor Sources: Amy O’Neal, "Snooky Pryor," Living Blues 6 (Autumn 1971): 4-6; Mike Rowe, "The Old Swing-Masters: Snooky Pryor," Blues Unlimited 137/138 (Spring 1980): 19-24 (Blues Unlimited ran interviews raw and unmediated, so quotes are edited). Jim O’Neal, Steve Wisner, and David Nelson, "Snooky Pryor: I Started the Big Noise in Chicago," Living Blues 123 (September/October 1995): 8-21; John Anthony Brisbin, "Pryor Arrangements," Blues Access 36 (Winter 1999): 53-54; Obituary for James E. Pryor in The Southern Illinoisan, October 20, 2006.

Snooky's partner on Planet 101, Moody Jones, played guitar and bass. He was born in Earle, Arkansas on April 8, 1908. Jones got his grounding in blues guitar by learning Blind Lemon Jefferson and Lonnie Johnson songs. He moved north to Wolf Island, Missouri, then to East St. Louis, and arrived in Chicago in 1939. He developed his musicianship further in the Maxwell Street market, playing with his first cousin, guitarist Floyd Jones, as well as Snooky Pryor, Johnny Shines, and other recently transplanted southerners who were not yet ready to join the union and play nightclubs. He also accompanied Robert Nighthawk during the peripatetic guitarist’s visits to Maxwell Street, and developed facility on the banjo and piano as well.

After recording with Pryor, Moody Jones never had another release under his name. He appeared on several sessions for JOB in 1951 and 1952. He sang three numbers on a session that took place on April 28, 1952, but Brown rejected them (Jones claimed it was because Brown thought his voice was too rough). The songs remained unreleased until Flyright put it them out in the early 1970s, revealing a voice that wasn't all that rough by blues singers’ standards. Moody Jones continued to record for JOB through January 1953; then he gave up the blues and joined a gospel group. He later became a minister. Moody Jones died in Chicago on March 23, 1988.

Moody Jones Sources: Mike Rowe, "The Old Swing-Masters: Moody Jones," Blues Unlimited 137/138 (Spring 1980): 5-15.

John O. Young, known as "Man" because he played mandolin as well as guitar, was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi, on January 1, 1918. In the mid-1930s he played with a string band in Rolling Fork, Mississippi. He said he worked with Sleepy John Estes and Hammie Nixon in Tennessee before moving to Chicago in 1940. In Chicago, he claimed to have performed with such notables as Memphis Minnie and Big Bill Broonzy, but one has to wonder how many of these were club dates, as Young was still essentially a street musician. By the late 1940s, he had become a regular in the Maxwell Street scene, playing with a cousin, guitarist Johnny Williams, along with Snooky Pryor, Floyd Jones, and Moody Jones.

Johnny Williams was born in Alexandria, Louisiana, on May 15, 1906. He was raised first in Houston and then deep in Delta blues territory, in Belzoni, Mississippi. His uncle played with Charlie Patton, and Williams got to know Patton, Jim Jackson, Howlin’ Wolf, and other legendary Delta bluesmen. Williams began performing in the late 1920s, arriving in Chicago in 1938. During much of the 1940s Williams played house parties, while first working in the defense industry and then in the Oscar Mayer factory at Division and Sedgwick. After World War II, he fell into the Maxwell Street scene, performing most often with Johnny Young.

During 1947, Young and Williams and a very young Little Walter were playing at the Purple Cat (2119 West Madison) on the city’s West Side. Williams says he joined the union to play at the Purple Cat, and we can assume that Johnny Young did as well. That year, Young and Williams also recorded their first record for Ora Nelle, a tiny label owned by Bernard Abrams of the Maxwell Radio Store. Young drew the vocals on "Money Taking Women," and Williams sang "Worried Man Blues."

Late the following year, up north, Young and Williams ran into Chester Scales in the Square Deal, which was right around the corner from his record shop. According to Williams, Scales was instrumental in getting Young and Williams a job there. Said Williams to interviewer John Anthony Brisbin in Living Blues, "We were the first ones to go there with a band."

According to Mike Rowe’s Chicago Breakdown, both of these recordings were done at United Broadcasting (301 North Erie) the same day, and that same day sold to different imprints—Man Young’s record to Planet and Floyd Jones’ record to Marvel. (This becomes less astonishing when we realize that Scales almost certainly owned a piece of each label—see below.) In Justin O’Brien’s amazing feature on Floyd Jones (The Dark Road of Floyd Jones, Parts 1 and 2, which appeared in Living Blues in 1983), the assertion is made that Scales recorded the acts in separate studios, which strikes us as highly implausible. Since Floyd Jones appeared on two sides, this session obviously followed the Snooky and Moody session, but it could have taken place just a few days later.

Johnny Young (mandolin, voc); Snooky Pryor (hca); Johnny Williams (eg).

Universal Broadcasting, Chicago, November or December 1948

| PL 103 | My Baby Walked Out on Me | Planet 103/104, Old Swing-Master 19-A, Boogie Disease BD 101/102, Nighthawk 107 [LP], Flyright FLYCD 20, Paula PCD-11, Charly CDGR 143-2, Indigo IGOCD 2095, Westside WESA 869 [CD] | |

| PL 104 | Let Me Ride Your Mule | Planet 103/104, Old Swing-Master 19-B, Boogie Disease BD 101/102, Nighthawk 107 [LP], Flyright FLYCD 20, Paula PCD-11, Indigo IGOCD 2095, Westside WESA 869 [CD] |

The Boogie Disease 2-LP set was called Take a Little Walk with Me—The Blues in Chicago 1948-1957 (1972); the Nighthawk LP, Chicago Slickers Volume 2 (1981). The identical Flyright (UK) and Paula (USA) CDs were released as by Snooky Pryor (1991). The Charly CD was issued as Chicago Blues: The Golden Era (1997), the Indigo CD was called Chicago Blues Hard Times (1999), and the Westside CD was issued as Pitch a Boogie Woogie If It Takes Me All Night Long—Seminal Post-War Chicago Blues (2001); the Westside was attributed to Snooky Pryor and Friends.

The trio of Young, Pryor, and Williams sounds like a street ensemble. On the slow blues, "My Baby Walked Out," it is not always 100% clear who is supposed to be playing the lead, and even when it gets the lead, Young’s mandolin is outcompeted in the balance by the electric guitar and the amplified harp. Pryor’s harmonica lends the number most of its personality as a gritty Chicago-style electrified country blues. The hard-driving "Let Me Ride Your Mule" is a more effective showcase for Young’s mandolin strumming and singing. In his subsequent performances on record, Young’s more subdued singing and playing were always in danger of being overshadowed by the accompaniment.

To Living Blues writer Justin O’Brien, Floyd Jones told a tale of Man Young going to Scales’ record shop to ask for money for his recording. Said Jones, "[Scales] told him he didn’t have no money. Johnny was just talkin’ loud and cussin’. He had been drinkin’. So [Scales hit] Johnny and knocked him down. It ain’t funny, but Chester called the police and put Johnny in jail. He had to pay $25 to get out of jail—and then got hit, too." Seeking retribution, Jones allegedly rounded up a friend, got a gun, then went over to the shop and forced Scales to hand over a roll of money. "We went back," said Jones, "and I gave Snook some money. I give Johnny Young some money, and I give Moody some money." Since Jones did not explain to O’Brien how Scales responded—and it is hard to believe that Scales would have done nothing—the story is hard to credit.

After his one record for Scales, Young made one session for Joe Brown’s JOB label, but Brown chose not to issue the sides, which encouraged Young—already dispirited about the music business—to retire from performing. (The session was done at an unknown date, and the masters may not have been preserved, as they have eluded every reissue program to date.) With the emergence of white interest in blues in the early 1960s, Young was lured out of retirement in 1963, and recorded—frankly, overrecorded—for Testament, Arhoolie, Milestone, Vanguard, Blues on Blues, Spivey, Bluesway, Rounder, and a variety of European labels. Young died on April 18, 1974 in Chicago.

After recording with Johnny Young for Planet, Johnny Williams appeared on just one further recording session; he shared studio time with Arthur "Big Boy" Spires, for Chance Records on January 17, 1953. Williams’ two items were not released until the 1970s when Charly in the UK and P-Vine Special in Japan put out "Silver Haired Woman" and "Fat Mouth." He stopped performing blues in 1959 after a conversion experience and entered the Baptist ministry. He reappeared on the scene in 1968 when he attended Little Walter’s funeral. Johnny Williams died in Chicago on March 6, 2006.

Johnny Young and Johnny Williams Sources: Jim O’Neal, "Johnny Young" [obit], Living Blues 17 (Summer 1974): 6; Sandy Sutherland, "Uncle Johnny Williams," Blues Unlimited 99 (Feb-Mar 1973): 7-9; John Anthony Brisbin, "Uncle Johnny Williams: Being Regular with the People," Living Blues 127 (May/June 1996): 28-41; Justin O’Brien, "The Dark Road of Floyd Jones, Part I" Living Blues 58 (Winter 1983): 13; Obituary of Johnny Williams in the Chicago Sun-Times, May 11, 2006.

Guitarist Floyd Jones, Moody's cousin, specialized in dark, brooding blues that often spoke to depressed economic and social conditions—"Stockyard Blues," "Dark Road," "Hard Times." He was born on July 21, 1917, in Marianna, Arkansas. After several years of dabbling with the guitar, Jones began playing it in earnest after Howlin’ Wolf gave him an instrument. Through much of the 1930s and early 1940s he worked the South as an itinerant musician. After visiting Chicago a couple of times, Jones moved to the city permanently in 1945, settling in the Maxwell Street neighborhood. In the city, the blues became more electrified, and Floyd Jones, who had been playing an acoustic guitar with an electric pickup, switched to a Gibson electric. He began playing on Maxwell Street and in non-union venues with such artists as Little Walter, John Henry Barbee, and Sunnyland Slim. In the fall of 1946, Floyd Jones teamed up with Snooky Pryor, soon joined by Moody Jones.

The three were playing in a club on Sedgwick, when Chester Scales happened by and offered to record the trio, having remembered seeing Snooky on playing on the street sometime earlier. However, on the day of the session, Floyd Jones missed out on recording "Telephone Blues" and "Boogie," because he could not be located. Scales made up for it by recording the trio with Floyd Jones as the leader on "Stockyard Blues" and "Keep What You Got," two classics of postwar Chicago blues written by Jones. Much to Jones’s everlasting distress, when the record was released, Scales put Snooky and Moody down on the label as the main artists, and listed Floyd as mere vocalist. He also claimed composition credit on both titles.

Floyd Jones (eg, voc); Snooky Pryor (speech -1; hca); Moody Jones (eg).

United Broadcasting Studio, Chicago, November or December 1948

| M 1312 | Stockyard Blues -1 ("Scales") | Marvel 702-A, Old Swing-Master 22A, Blues Classics BC 8 [LP], Boogie Disease BD 101/102 [LP], Flyright FLYCD 20, Paula PCD-11, Charly CDGR 143-2, Indigo IGOCD 2095, Westside WESA 869 [CD], Classics 5130 [CD] | |

| M 1313 | Keep What You Got ("Scales") | Marvel 702-B, Old Swing-Master 22B, Blue Horizon LP2, Boogie Disease BD 101/102 [LP], Muskadine 1 [LP], Muskadine M 100 [LP], XTRA [Br]1133 [LP], Flyright FLYCD 20, Paula PCD-11, Indigo IGOCD 2095, Westside WESA 869 [CD], Classics 5130 [CD] |

The Blues Classics LP was released as Chicago Blues—The Early 1950’s (1965). Blue Horizon LP2, Let Me Tell You about the Blues Volume 1, was released in Britain in 1966, in an edition of 99 copies to get around potential copyright issues; there was no Volume 2. The Boogie Disease LP came out in 1972 as Take a Little Walk with Me—The Blues in Chicago 1948-1957, and the Muskadine LP was On the Road Again: An Anthology of Chicago Blues 1947-1954 (c. 1969 for Muskadine 1 and 1971 for Muskadine 100). The Xtra is the 1973 UK release of the Muskadine package. The Flyright and Paula CDs are identical and were both released as by Snooky Pryor (1991). The Charly CD was titled Chicago Blues: The Golden Era (1997), the Indigo CD was called Chicago Blues Hard Times (1999), and the Westside CD was called Pitch a Boogie Woogie If It Takes Me All Night Long—Seminal Post-War Chicago Blues (2001). This last was billed as by Snooky Pryor and Friends. Classics 5130, Floyd Jones 1948-1953, is a CD released in 2005; the final session on the CD actually dates from 1954.

Jones’ "Stockyard Blues" features well-developed lyrics about the financial stress of a work stoppage; Snooky and Moody provide the licks that create the sense of despair and defeat, although Snooky’s spoken asides lighten the mood temporarily. Despite the cautionary lyrics, "Keep What You Got" is a fast swinging boogie. The number probably dates back to the early 1930s when Jones was associated with Howlin’ Wolf, because it would be one of the very first tunes that Wolf recorded, for Modern in 1951. (Jones and The Wolf also shared a predilection for eerie modal numbers—"Dark Road" and "Early Morning" are noteworthy examples from Jones' repertory.) Jones first calls for Buddy (his nickname for Moody) to play—Moody then works up some spirited licks on the second guitar—and then calls out for Snooky—and Snooky blows with gusto. (Existing discographies have put Moody Jones on string bass, but he is in fact playing second guitar on both sides.)

Despite the excellence of both sides, which has earned them a legendary status, the record got minimal circulation on Marvel and probably didn’t sell much better on Old Swing-Master. Sunnyland Slim was on record by this time, and Muddy Waters had made a breakthrough a few months earlier, when Aristocrat released "I Can’t Be Satisfied" in June 1948. But postwar urban blues were not yet featured in most clubs, nor much played on radio; the market for this music was still emerging. One consequence, however, of having a recording out under his own name, was the opportunity to play in Union venues. According to his card on file at the Chicago Federation of Musicians, Floyd Jones joined Local 208 on May 21, 1949.

In May 1949, Floyd Jones went on to record with Sunnyland Slim for Tempo-Tone, making another classic of blues despair, "Hard Times." His next opportunity would come with Joe Brown’s JOB label in March 1951, when he made "Dark Road" with Sunnyland Slim and Moody Jones. By the end of the year, Floyd Jones had moved to Chess, where he recorded two sessions. Jones' second rendition of "Dark Road," cut for Chess in December 1951 in fratricidal competition with his JOB version, became his most successful record and the most enduring part of his recorded legacy. Jones returned to JOB for a session in Janury 1953, recording another standout, "On the Road Again." In 1954 he moved to Vee-Jay, where he made "Ain’t Times Hard."

A new White audience created a market for the pioneers of Chicago blues, and in 1966 Pete Welding recruited Floyd Jones to record an LP with Eddie Taylor for his Testament label. Jones subsequently recorded for the Swedish Magnolia label (with Big Walter Horton in 1970) and Earwig (with Honey Boy Edwards, Sunnyland Slim, and Kansas City Red in 1979, and with Big Walter in 1980). Floyd Jones died in Chicago on December 19, 1989.

Floyd Jones Sources: Mike Rowe, "The Old Swing-Masters: Floyd Jones," Blues Unlimited 137/138 (Spring 1980): 15-18; Justin O’Brien, "The Dark Road of Floyd Jones, Part I" Living Blues 58 (Winter 1983): 4-13; Justin O’Brien, "The Dark Road of Floyd Jones, Part II" Living Blues 59 (Spring 1984): 6-15.

Robert Perkins was an alto saxophonist who had been on the Chicago scene for a few years. His first known writeup appeared in The Billboard 1944 Music Year Yearbook, which ran two photos of "Bob Perkins The Sax-o-maniac and his Swing Quartet" with Earl Hyde on drums, George Dawson on guitar, and Everette McCrary on bass (our thanks to Bo Sandell for information on this source).

On November 2, 1944, Perkins filed an "indefinite" contract with Millie's Lounge with Musicians Union Local 208; this was followed by another indefinite contract on November 16. The proprietors of Millie's probably considered Perkins the rough equivalent of Buster Bennett. Perkins picked up again at Millie's in July 1945; he posted a 10-week contract on July 19. And on September 6, he filed an indefinite contract with the Garrick Lounge, renewed on October 18.

After an extended absence, Perkins began showing up again on the contract lists in September 1946. His contract with the General Lounge for two days was accepted and filed on September 5, 1946; he followed this up with a four-week contract (posted October 3). He then moved over to the Sky Club (two-week contract accepted and filed on November 7, 1946). In May 1947, Perkins resurfaced as a leader at Jimmy's Palm Garden (six weeks with an option; contract filed on May 15). The Palm Garden contract was extended on July 3 (six more weeks, with a 12-week option). By early November Perkins was at the Rag Doll (indefinite contract posted on November 6). In February 1948, he was holding forth at the Macomba Lounge (contract filed on February 5); he probably remained till late March, when he was briefly replaced by Tommy "Madman" Jones. On May 6, 1948, Perkins filed another contract with the Rag Doll (for 3 weeks and 2 days). On June 3, Perkins posted a 10-week contract with the Green Parrot; on August 5 his indefinite contract with Jimmy's Palm Garden was accepted and filed. And on November 4, 1948 he filed a two-week contract with Club 21 and an indefinite contract with the Rag Doll. In March 1949 his trio with Floyd Morris on piano and Norman "Flip" Gaines on drums was working as the house band at the Music Bowl, a club in the Loop (Down Beat, "Chicago Band Briefs," March 25, 1949, p. 4); he had been there since New Year's, posting an indefinite contract with the "New Music Bowl" on January 6. It's kind of obvious which nightspot is commemorated in "Boogie Woogie Bowl."

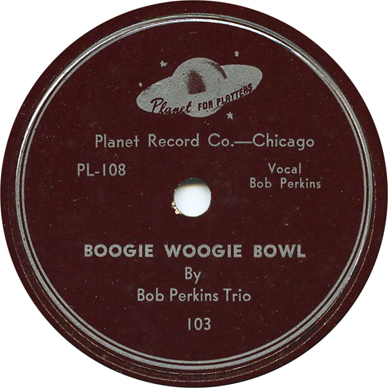

Bob Perkins (as, voc); Floyd Morris (p, voc); Norman "Flip" Gaines (d).

Chicago, between January and March 1949

| PL-108 | Boogie Woogie Bowl [BP, ens voc] | Planet 103, Old Swing-Master 17A | |

| PL-109 | Fool Again -1 [FM voc] | Planet 103, Old Swing-Master 17B |

Planet 103 carrries a release number that is distinct from the matrix numbers, and the label now sports a Saturn logo with "Planet for platters" emblazoned along the rings. Once again the MP monogram is visible in the wax on both sides.

Perkins’ trio had a sax-piano-drums configuration, which in those days was still broadly familiar to Chicago clubgoers. Since Perkins was a jazz player with leanings in the Louis Jordan direction, and he is not known to have frequented the Square Deal or other clubs in Chester Scales’ neighborhood, this may be the one Planet release that Scales was not involved in.

The Billboard review of the record in its Old Swing-Master incarnation was unfavorably disposed toward "Boogie Woogie Bowl," giving it ratings of 46-46-44-48: "Unpromising novelty ditty in boogie tempo gets a mediocre warbling and instrumental rundown by a sax-piano-drums trio." It's easier to like "Bowl" today; the number is in the Louis Jordan style, which perhaps Billboard reviewers were getting tired of. Although Perkins is not the consummate vocal entertainer that Jordan was, he is in control of his patter on this musical advertisement for the club, which manages to work in praise for the music ("There's boogie woogie, and a little bebop too"), the food, the drinks, and the service to be had at the establishment.

"Fool Again" is the customary lounge ballad B-side, competently crooned in a smooth baritone by Floyd Morris; the only distinctive feature is a rather eccentric vocal tag at the end. It did a little better with Billboard, coming in at 55-57-55-53: "Warbler and sax compete to be heard on a modern ballad number of some promise." Skepticism about Old Swing-Master's distribution definitely helped to lower the numerical ratings.

The biggest attraction on these sides is Perkins' alto sax (misidentified as a tenor in some sources). He was a Swing player with an attractively tart tone that sets him off from the Hodges-style players like Sax Mallard, Porter Kilbert, Nat Jones, and Willie Randall, the Bird emulators like Flaps Dungee and Goon Gardner, and the gutbucket artists like Buster Bennett. Perkins displays nice fluidity and good ideas in his theme statement and solo on "Bowl." His introduction, vocal accompaniment, and solo on "Fool Again" are refreshingly low on schmaltz but some listeners may find the second half of the solo overly busy. Floyd Morris does not solo on either side; Flip Gaines gets a drum break just before the conclusion of "Boogie Woogie Bowl." Our thanks to Steve Wisner for providing dubs of these very rare sides. Apparently they have never been reissued.

For years, we thought the Planet/Old Swing-Master was Perkins' only release as a leader. The Music Bowl was in financial trouble when the Down Beat item ran, and, sure enough, Perkins quickly moved to the Nob Hill Cocktail Lounge (2 week contract accepted and filed on April 7, 1949). After some time working outside Local 208's area, Perkins resurfaced in July ("indefinite" contract with Ralph's Club posted on July 7). After longer absences, he reappeared in Chicago in the Fall of 1950. In September, the "Chicago Chatter" column (we think that was in Cashbox, but as we are drawing this item from a First Pressings volume, we aren't sure of the periodical or the exact date) referred to "Alto man Bob Perkins leading a trio at the Ship, Madison and Woods, with bassman Johnny Pate and pianist Floyd Morris." A West Side establishment, the Ship Show Lounge was located at 1801 West Madison. The trio moved to the 125 Restaurant and Lounge in November 1950 (4 weeks with options, contract posted November 2). It appears that Floyd Morris had left the combo after the gig at the Ship, because he filed his own contract with the Century Club on October 19.

A Bob Perkins Trio with piano and drums made a second 78 rpm single around December of 1950. Personnel changes had been happening, and the other musicians weren't named on the labels, so we don't know who they were. The single was credited to Bob Perkins | Vocal | Instrumental; the other two instruments can be heard along with the leader's alto sax. The company was Mar-Vel', with a PO Box in Hammond, Indiana; it had no connection with Chester Scales' operation in Chicago. According to Paul Solarski (emails of December 6, 2022), Mar-Vel' was in operation from 1949 until 1954 (discogs.com suggests it was in business until 1965 or 1966). The company was run by Harry Glenn, whose name appears on the labels to the Bob Perkins single. Glenn seems to have favored Country performers and rarely recorded black musicians, but the Perkins trio had caught his attention. Maybe Glenn saw a live appearance in Gary or Hammond.

>On Mar-Vel' 800, which used a blue label, in an early style for Mar-Vel': "Harry Glenn, Mgr." in the copy, but not "BMI Affiliate." The A side was a rendition of "Dinah" and the B side was "Drinking Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee," which was still garnering covers in 1950. Perkins sang on both sides, which also include vocal contributions from the other two members of the trio. On "Drinking Wine," vocal duties limit the leader to an introduction on the alto sax, plus a brief tag at the end. "Dinah" gives him room for a substantial solo, on which his tart tone and basically Swing style can be heard to advantage. In case anyone thought he didn't know about bebop, Perkins works in a Charlie Parker quote. The full matrix numbers (in the trailoff area only) are MV30476 M R S MV800A for "Dinah" and MV30475 M R S MV800B for "Wine." The sides were recorded at Modern Recording Studio in Chicago, which used a work order and numerical suffix system for matrix numbers. Work order 3047 dates the session around December 1950. Other tracks for Mar-Vel' were cut on the same occasion. We know this was the case for both sides of Mar-Vel' 600, by George Wilson ("With Instrumental Accompaniment"), which the company counted as a hit (and reissued in 1956). The Wilson titles were "I Want Somebody to Love Me" and "Crimson Rose"; on the 1950 release, the trailoff area carried M R S MV30474 and M R S MV30473, respectively. Our thanks go to Paul Solarski for label photos, matrix numbers, and dubs of both sides of a super-rare Bob Perkins release.

Bob Perkins reappeared in Local 208's domain in September 1951 (indefinite contract at Ralph's Club posted on September 6). On November 15, 1951, he posted a contract (the time period was inadvertently left out) with the Blue Note; in September 1952 he showed up for a final time at the Hi-Note Lounge (his contract for 2 weeks was accepted and filed on September 4).

It looks like Perkins was spending a lot of his time on the road from 1949 onward, and we don't know what happened to him after 1952. Bob Perkins' card was not in the membership file that Local 208 passed on to the Chicago Federation of Musicians when it merged with Local 10 in January 1966; by then he had either retired from music or left Chicago for good.

Floyd Morris, on the other hand, remained on the club scene through the end of the 1950s; sometimes identified on the contract lists as Floyd Morris, Jr., he played solo or led a trio in the clubs, worked regularly for other leaders, and recorded with Red Saunders and Johnnie Pate, among others. As a member of Pate's groups, he played on two LPs for the Salem label, both made in late 1956. During the 1960s and 1970s he was a mainstay session musician for the Chicago soul music industry. The biggest audience ever to hear his piano playing consisted of the buyers of "Soulful Strut," by Young-Holt Unlimited, a 1968 recording that sold two million copies. Floyd Morris died in 1988.

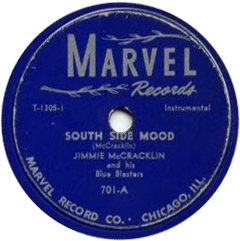

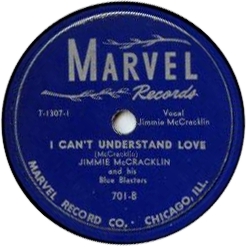

Two sides by Jimmy McCracklin are the only non-Chicago recordings that appear on the Marvel and Planet imprints. Like the other recordings from those labels, the two sides also ended up on Old Swing-Master (along with two more that, so far as we know, hadn't put in an appearance on Marvel first). The sides were originally released on Trilon, located in Oakland, California where McCracklin was then based. We do not know whether the other releases used the group name Jimmie [sic] McCracklin & His Blues Blasters.

Jimmy McCracklin (p, voc); Robert Kelton (eg); unidentified (b).

Oakland, 1948

| T 1305-1 | South Side Mood (McCracklin) | Trilon 244, Marvel 701-A, Old Swing-Master 24A | |

| T 1307-1 | I Can’t Understand Love (McCracklin) [JM voc] | Trilon 244, Marvel 701-B, Old Swing-Master 24B |

Jimmy McCracklin was born on August 13, 1921, in Saint Louis. He began to make records in 1945 for Globe on the West Coast, and in 1948 he was recording for Trilon.

Trilon, operated by Rene LaMarre, had aspirations to be a large outfit, because it maintained a distribution office in Chicago at this time, at Roosevelt Road and Spalding (1208 South Spalding). Of course, the existence of the distribution office makes it doubly mystifying why a larger out-of-town company felt the need to lease the sides to Marvel.

A clue is that Trilon 244 (and its companion, Trilon 245, which would also show up later on Old Swing-Master 25 without making a stop at Marvel) contained the last four sides to see release on the label. The company had been around since 1946, and had put out at least 43 releases. But in late 1948, it was going under, and apparently someone in Trilon’s Chicago office thought Marvel could do something with the two McCracklin sides.

While this sounds like a bit of stretch, consider what the Snooky Pryor and Floyd Jones said about Trilon. First, Snooky's recollection in his Living Blues interview with Jim O’Neal, Steve Wisner, and David Nelson ("Snooky Pryor: I Started the Big Noise in Chicago"). Pryor said that after Scales had put out the Snooky and Moody record, and he could see that it was selling, he went back to Scales to collect royalties. Scales rebuffed him and said he had sold the master to Trilon. Pryor then went down to Trilon to confront the guy who now supposedly had the record. After several weeks of hassling him, he discovered the Trilon shop was closed up, and the next thing he finds out is that record ended up with Al Benson. Second, what Floyd Jones related to Justin O’Brien in Living Blues: Scales "had a little label, but he was backed up through Trilon, and then one while he was with Marvel. That’s who he sold that number to—Marvel. Then later on Al Benson got it."

Scales had some kind of connection with someone at the Trilon distribution office in Chicago. Curiously, while both Pryor and Jones asserted that Scales had a label that put out their releases, neither identified it as Marvel or Planet!

Meanwhile, McCracklin enjoyed a long career in R&B, with stops at Modern, Swing Time, Peacock, Imperial, Hollywood, Irma (a latter-day Bob Geddins operation), Checker, Mercury, and Minit. Most recently he recorded for Bullseye Blues.

With a total of five releases between them, the labels look to have been the work of a small-scale entrepreneur, like the proprietor of a mom and pop record store. (Several other Chicago indies, such as Ora Nelle, Club 51, and Ping, came into being exactly this way.) The obvious candidate would have to be Chester Scales, because Bishop, Pryor, and Jones all thought he had a label, without specifically connecting him to Planet or Marvel. Yet we have no contemporary report that links Scales to those labels. Indeed, we have Mike Rowe’s report in Chicago Breakdown about Scales "selling" Man Young and Floyd Jones recordings to Planet and Marvel. But how did Rowe arrive at this information? One suspects extrapolation from the evidence he had. In fact, Neil Slaven, in his notes to a 2001 CD compilation on Westside that includes JOB tracks by Snooky Pryor and Floyd Jones, flatly states that Scales owned Planet and Marvel.

It turns out that under phonograph record distributors and wholesalers, the March 1948 Chicago telephone directory lists one Planet Record Sales at 831 South State, which advertised itself as a distributor of Vitacoustic Records. As Old Swing-Master was founded on the ruins of Vitacoustic’s "race" series and later reissued the Marvels and Planets, this is an intriguing piece of evidence. We wonder whether Planet Record Sales used the "Planet for platters" slogan that can be seen emblazoned across the rings of Saturn on some of the 78s. The slogan sounds like one that a wholesaler would use, but, unfortunately for researchers working over 50 years after the fact, the company didn’t purchase a display ad in the phone book. What's more, Planet Record Sales was no longer listed in the 1949 phone book, leading us to surmise that it went out of business before Old Swing-Master took over the Planet releases in May of that year.

So let us mark our trail of speculation for those who may wish to follow. We have an individual at Trilon that Scales presumably unloaded his Snooky and Moody and Floyd Jones sides to—according to the testimony of the musicians. Suppose, however, that this individual was not really representing Trilon, but freelancing—putting out records on Marvel in partnership with Scales. Meanwhile Scales ran Planet in partnership with someone at the Planet distribution firm; he may even have owned a piece of that short-lived distributor himself. The person at Trilon may have been involved in Planet as well.

Here's what we think is most likely: Lacking the capital to get records mastered, pressed, and marketed on his own, Chester Scales set up the Marvel and Planet imprints in partnership with other individuals, who were associated, respectively, with the Trilon distributor and the Planet wholesaling and distributing operation. The musicians—while providing invaluable testimony to blues historians—were somewhat out of the loop, besides being naïve about the record business, and thus never quite grasped the exact relationships between Scales, Trilon, and other record business operations of the day. (Of course, judging from the stories about the way he fended off requests for royalties, Scales probably didn't want these to be easy to grasp!)

One further mystery—there are gaps in the 100 matrix series for Planet and the 1300 matrix series for Marvel, possibly indicating that more sides were recorded (after all, the industry standard was 4 tunes per 3-hour session). If there were any unreleased sides, however, the trail after all this time is stone cold.

According to Bishop, Chester Scales owned a number of small record shops. At the same time he ran the shop on Sedgwick, he also maintained one at 211 West Division. Around 1952, after closing the old operations, Scales established a new record store, Ogden Radio and Record, at 3644 West Ogden, and then a second store at 3351 West Ogden. A search of the telephone directories has turned up just the Sedgwick store, but the others may have been small variety stores that sold records and radios as well.

Around 1953, Chester Scales left Clara and moved to the small town of Edgerton, Wisconsin, established a trucking business, took up with another woman, and started another family. He died on August 29, 1997, in Highland, a rural village in Iowa County, Wisconsin.

Sources used for Planet and Marvel: Robert Pruter interview with Charles Bishop, 23 October 2003; Mike Rowe, Chicago Breakdown (London: Eddison Press, 1973): 54-58; Classified Telephone Directory of Chicago March 1948 (Chicago: Donnelley, 1948): 1175; research by Eric LeBlanc.

Click here to return to Red Saunders Research Foundation page.