Revision note: Our thanks to Brad Barrett for pointing out the Ora Nelle sides that were employed in the CD that accompanies the 2008 Shanachie DVD, And This Is Free: The Life and Times of Chicago's Legendary Maxwell Street.

The legendary Ora Nelle label was run out of a record store, and operated for a year or two, managing just two releases. Another 10 sides of alternate takes and unreleased material make Ora Nelle's entire legacy just big enough to round out one LP.

Bernard Abrams, who was probably born in 1919, opened Maxwell Radio and Record Company at 831-833 West Maxwell Street in 1945. He converted what had been his family's house into the store (the Abrams family continued to live nearby). Operated by Bernard and his wife Idel, the store was in the center of an open air market that operated each Saturday and Sunday morning, where many blues musicians would perform outdoors. By 1945, the market area had already been around for many years. Like some other record store owners during the 1940s and 1950s, Abrams acquired a disk-cutting machine, which allowed customers to make demos on the premises. Most such demos, like those reportedly made by Muddy Waters, went out the front door after the musician had paid for them. But after a couple of years, the idea took hold of making a commercial release of some of the down-home style blues that could be heard in the surrounding area.

Ora Nelle was named after a female relative, and the release series began at 711—not for the numerological reasons that later led Sun Ra to put 711 on his LP The Magic City, but on account of the winning combinations when shooting dice. The label never had distribution; Ora Nelles were sold out of the store, where copies were still in stock 20 years later, or resold by people who had bought them there.

The label produced two official releases, both of which came out in 1947. Other blues artists were recorded in the store with an eye to possible release. Their direct-cut Presto 8-inch lacquers, along with those bearing alternate takes of three of the released items, remained in the possession of Bernard and Red Abrams. The exact dates on these unreleased items are not always clear; the Sleepy John Estes sides, at least, could have been made a couple of years later. Though played more often than was ideal, and on old equipment, the lacquers were kept in the store.

In 1969 George Paulus, who had been a regular customer at Maxwell Street Record and Radio for several years, bought the surviving lacquers from the Abrams family. He subsequently released all 14 sides on an LP on his Barrelhouse label (in 1974), then, in improved sound, on his St. George label (1983). In the 1990s, P-Vine licensed the material for release in Japan, leading to an LP and a CD. These were and still are the only systematic reissues of Ora Nelle material. Four sides were also included in the CD that accompanied a 2008 DVD release from Shanachie, And This Is Free: The Life and Times of Chicago's Legendary Maxwell Street.

Here is George's account of Maxwell street, the store, and the acquisition of the label:

A friend and I first went to Maxwell Street (only a few people called it the Maxwell Street Market) in eighth grade. We skipped Sunday Mass and took the bus from the white South side of Chicago to the near West side cross streets of Halsted and Maxwell.

Stepping out of the green and yellow bus, we took a short walk down a street lined with card sharks, junk sellers, and Jewish merchants pulling your elbow or coat into their stores. Our senses were dazzled; we looked around in wonderment at the random mix of humanity and stray dogs. The street was noisy, perfumed by Polish sausage or barbequed meat or mixed Mex on a grill, along with garbage that had been left to rot on the curbs.

West on Maxwell, a few blocks down on the left, was Maxwell Street Radio and Record shop. Cheap, garishly painted, flaking wood, iron grates and sliding burglar gates covered the facade. Above the door was a cheap speaker blasting out old blues 45s. We made a verbal note to check out the store on the way back and kept on walking, stopping to look in the window of the shop that sold hoodoo incense, potions, and old books. A dozen cats walked or leaped around inside. There was nothing like this in our middle class white neighborhood. A fat black hoodoo man dressed in loud glittering robes sat on a chair curbside. We eyeballed him and he glared at us while tapping his wooden staff.

Walking down another block we heard live music with blasting guitar, blues vocals and amplified harp. Our pace quickened as we turned a corner and saw: Big John Wrencher on vox and harp, Little Buddy Thomas on elecric guitar and Playboy Coot Vinson lazily hitting his ancient drums. One-armed Big John Wrencher slithered around, jumped, whooped, and hollered as he blew into his harp mike. The band passed a pint of whiskey around, at eleven in the morning. An ancient small black man approached the spectators with an open cigar box, cajoling the people who didn’t toss in coins. We were immediately converted and returned almost every Sunday. Soon we would be requesting songs and slipping a dollar in Big John’s pocket.

On our way back to the bus stop we climbed the few cement stairs into the Maxwell Record shop. It was filled with old televisons. Radios were being operated on amid the dust. The place looked like it was a hundred years old. Big and pleasantly gruff Bernie Abrams looked at us and asked what we wanted as he performed an autopsy on a customer's radio. “Records,” we happily replied. He simply pointed to the middle of the store.

Behind the U-shaped counter—like a throne with 8 by 10 publicity photos stapled to the front and sides—sat Bernie’s wife Red [Idel, as she was generally known to the customers]. Fair skinned with bright red hair, she was elevated a couple feet above floor level. She smiled and asked what records we were looking for. “Uh, Muddy Waters , Howlin’ Wolf, Jimmy Reed,“ we replied. “ Oh I think we have some of those,” Red coyly responded. She pulled out 2 boxes filled with about 50 or more 45s each. She pulled the sides out and clucked, “ oh here’s a nice one.” She went through the titles, showing us the little 7-inch discs. We each selected 3 or 4 platters.

We had been repeating our Maxwell Street expedition almost weekly when one day Red mentioned that she and Bernie had put out Little Walter’s first record, along with Othum Brown. A stack of each Ora Nelle 78 was on the floor behind her, just slightly out of view. She played the Walter, then the Johnny Young, and we bought one each. The sound was wild and she smiled all the way through the one-minute record demonstration. For us this was somewhere between 8th grade summer and freshman year in high school. Soon I would be buying 3 or 4 copies weekly for “ friends”. Red never liked selling too many to each person. I was soon shipping the 78s to England and France.

One Sunday Red surprised me. “I have a gift for you! It’s a really old record from the 1920s,” She smiled. It was an Autograph 78 with a small hairline crack. I graciously accepted her gift, damage and all. No reason, just a gift out of the blue. I called Paul Sheatsley of Record Research later that evening and asked if he had any interest in it. “ Cracked? No interest,” He responded. “I thought it sounded pretty good and it played over the hairline,” I replied. “ Jesus Christ,” he shouted “you have the record,” “That’s one of the rarest jazz records ever made. 4 to 5 known copies. You’ll get a fortune for it.”. Paul was extremely honest and schooled my jazz knowledge for years.

As the years passed and I became a deeply hooked record collector I got around to asking Red if they had recorded any other blues singers. "Have you heard of Jimmy Rogers?" “Sure I replied, “He’s one of my favorites!” "Oh yes, we did some things for local boys and they took their acetates home. Muddy did one here but he took it with him." Mythical or not, the thought of such acetates was pure ecstasy.

“Let me see if I can find it...hmm, oh here it is!” she again coyly replied. Red pulled an eight inch acetate of Rogers with Little Walter on harp. “ Wow that’s great, can I buy that one” I gently asked. “Oh, not right now, maybe someday,” she answered with a smile. The record stayed on my mind for a year. I finally bought all the Ora Nelle masters in 1969 when I turned twenty one. Seemed like a fitting birthday present...

I did the deal with Bernie. He handed over the acetate masters and Red looked hurt and was silent. She had had the acetates under the counter for years. Her musical children. When Bernie said I could take the pictures from the wood counter Red looked like she was going to faint. As each staple was removed I could almost hear her painful moans. No smiling Red today. “ Please don’t take them all,” she quietly pled.

I asked Bernie where he recorded Walter and Rogers. He matter of factly replied, “We had a little disc cutting machine in the front of the shop. Recorded right about where you are standing. The boys just sat on chairs and played. Hell, Walter played harp on the steps when he was relaxing.” Red came over and said ,”Walter was a very nice talented fellow and we wished him all the best.” "Ora Nelle Blues," sung by Othum Brown, was named after one of Red’s relations. “We couldn’t get the distribution so we sold the records right out of the store.” Bernie said the store looked pretty much the way it did back them. A little cleaner, with shiny varnish on the wooden floors. “It was nicer back then. Not the violence we have today,” Bernie grimaced. Red silently nodded.

Ora Nelle was the first label to record the revolutionary blues harmonica player Little Walter, the only label to record guitarist Othum Brown, and the second to record guitarist Jimmy Rogers. Its surviving holdings also include sides by Sleepy John Estes, Johnny Temple, and a guitar player known as "Boll Weevil." Restricting itself to blues performances accompanied by one to three instruments, Ora Nelle was in the right place at the right time to capture emerging down-home blues sounds. The only competitors in this niche were other small Chicago-based independents, such as Aristocrat and Opera, also founded in 1947. Planet and Marvel would follow in 1948, Tempo-Tone and JOB in 1949.

In the 1950s Little Walter would become one of the giants of Chicago’s postwar blues boom, but in 1947 he was all of 17 years old and his renown was strictly local. He was born Marion Walter Jacobs on May 1, 1930 in Marksville, Louisiana. Walter left his home with his harmonica at the young age of 13 to become an itinerant street musician, going to New Orleans, then up to Memphis, then St. Louis, and finally Chicago in 1946. He took up performing in the Maxwell Street market. The following year he made his first recordings right there on Maxwell Street, for Ora Nelle. His next sessions would be for Tempo-Tone, in May 1949, and for Parkway, in January 1950. Chess finally began recording him with Muddy Waters in July 1950; he went solo two years later, after his first release for Checker scored a big hit.

About Othum Brown, hardly anything is known. Brown was reportedly from Richland, Mississippi, and left the music scene in the early 1950s, spending his later years in New York City. Ora Nelle 711, plus two alternate takes cut in the store, make up his entire recorded legacy.

Marion Walter "Little Walter" Jacobs (hca); Othum Brown (eg, voc).

Maxwell Radio Record Company, Chicago, 1947

| tk. 1 | Ora-Nelle Blues (Othum Brown) [That's Alright*] | Ora Nelle 711A, Chance 1116*, Muskadine 1, Muskadine M 100, XTRA [Br] 1133, Barrelhouse BH-004, St. George STG-1001, P-Vine [J] PCD-1888, P Vine Special [J] PLP-6714 | |

| tk. 2 | Ora-Nelle Blues (Othum Brown) | Barrelhouse BH-004, St. George STG-1001, P-Vine [J] PCD-1888, P Vine Special [J] PLP-6714 |

Art Sheridan licensed Ora Nelle 711 for reissue on his Chance label—it was the only reissue from the label to take place before the blues revival of the 1960s. Part of his agenda is revealed by the retitling of this side, as "That's Alright." For "Ora Nelle Blues" was the same piece as "That's All Right," which in the meantime had become a hit for Jimmy Rogers—on Chess in 1950. Sheridan didn't bother to mention Brown on the label, either.

Muskadine 1 was an LP released around 1969. Muskadine M 100, with the same tracks in a different order, was released in 1971, and XTRA 1133 was its British counterpart, released in 1973. All were titled On the Road Again: An Anthology of Chicago Blues 1947-1954.

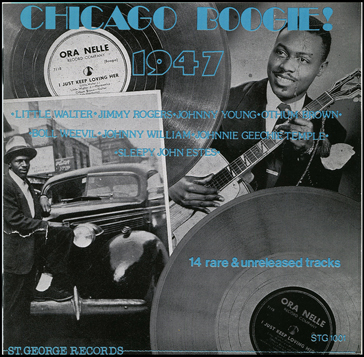

Barrelhouse BH-004 was an LP released in 1974, under the title Chicago Boogie!. St. George STG-1001 was an LP released in 1983 under the title Chicago Boogie! 1947; all tracks were the same as on Barrelhouse BH-004, but in a different order and with improved sound. P-Vine PCD-1888, released in Japan in 1993, used the cover art of the St. George LP and the track order of the Barrelhouse. P-Vine Special PLP-6714, Chicago Boogie, was an LP that reused George Paulus' cover art for Barrelhouse; it was supposedly also released in 1993.

Little Walter (hca, voc); Othum Brown (eg).

Maxwell Radio and Record Company, Chicago, 1947

| tk. 1 | I Just Keep Loving Her (Little Walter J.) [Just Keep Loving Her*] | Ora Nelle 711B, Chance 1116*, Barrelhouse BH-004, St. George STG-1001, P-Vine [J] PCD-1888, P Vine Special [J] PLP-6714 | |

| tk. 2 | I Just Keep Loving Her (Little Walter J.) | Barrelhouse BH-004, St. George STG-1001, P-Vine [J] PCD-1888, P Vine Special [J] PLP-6714 |

Art Sheridan released Chance 1116 in May 1952, which gave him a slight jump on Little Walter's big hit, "Juke." In addition to whatever interest he had in Little Walter, Sheridan wanted the other side because a later version of it had been a hit record (see above).

Barrelhouse BH-004 was an LP released in 1974, under the title Chicago Boogie!. St. George STG-1001 was an LP released in 1983 under the title Chicago Boogie! 1947; all tracks were the same as on Barrelhouse BH-004, but in a different order and with improved sound. P-Vine PCD-1888, released in Japan in 1993, used the cover art of the St. George LP and the track order of the Barrelhouse. P-Vine Special PLP-6714, Chicago Boogie, was an LP that reused the Barrelhouse cover art; it was supposedly released in 1993.

John O. Young, known as "Man" because he played mandolin as well as guitar, was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi, on January 1, 1918. In the mid-1930s he played with a string band in Rolling Fork, Mississippi. He said he worked with Sleepy John Estes and Hammie Nixon in Tennessee before moving to Chicago in 1940. In Chicago, he claimed to have performed with such notables as Memphis Minnie and Big Bill Broonzy, but one has to wonder how many of these were club dates, as Young was still essentially a street musician. By the late 1940s, he had become a regular in the Maxwell Street scene, playing with a cousin, guitarist Johnny Williams, and at various times with harmonica player Snooky Pryor, guitarist Floyd Jones, and Floyd's guitar playing cousin Moody Jones.

Johnny Williams was born in Alexandria, Louisiana, on May 15, 1906. He was raised first in Houston and then deep into Delta blues territory, in Belzoni, Mississippi. His uncle played with Charlie Patton, and Williams got to know Patton, Jim Jackson, Howlin’ Wolf, and other legendary Delta bluesmen. Williams began performing in the late 1920s, arriving in Chicago in 1938. During much of the 1940s Williams played house parties, while first working in the defense industry, then in the Oscar Mayer factory at Division and Sedgwick on the Near North Side. After World War II, he fell into the Maxwell Street scene, performing most often with Johnny Young.

During 1947, Young and Williams and a very young Little Walter were playing at the Purple Cat (2119 West Madison) on the West Side. Williams says he joined the Musicians Union to play at the Purple Cat, and we can assume that Johnny Young did as well. Ora Nelle 712 was the first commercial recording for either musician.

John Young (mand); Johnny Williams (g, voc).

Maxwell Radio and Record Company, Chicago, 1947

| Worried Man Blues (William) | Ora Nelle 712A, Barrelhouse BH-004, St. George STG-1001, P-Vine [J] PCD-1888, P Vine Special [J] PLP-6714, Shanachie 6801 [DVD/CD] |

John Young (mand, voc); Johnny Williams (g).

Maxwell Radio and Record Company, Chicago, 1947

| tk. 1 | Money Taking Woman (Young) | Ora Nelle 712B, Barrelhouse BH-004, St. George STG-1001, P-Vine [J] PCD-1888, P Vine Special [J] PLP-6714 | |

| tk. 2 | Money Taking Woman (Young) | Barrelhouse BH-004, St. George STG-1001, P-Vine [J] PCD-1888, P Vine Special [J] PLP-6714 |

One take of "Money Taking Woman" was included in the CD that accompanied Shanachie 6801. This was a DVD, released in 2008 under the title And This Is Free: The Life and Times of Chicago's Legendary Maxwell Street. The DVD combined two films: And This Is Free from 1964 and Maxwell Street-A Living Memory. The CD compiled work by various blues artists with a Maxwell Street connection, ranging from Papa Charlie Jackson to Muddy Waters, including four sides from Ora Nelle.

Late the next year, up north, Young and Williams ran into Chester Scales in the Square Deal club, which was right around the corner from his record shop at 941 North Sedgwick. According to Williams, Scales was instrumental in getting Young and Williams a job at the Square Deal. Said Williams to interviewer John Anthony Brisbin in Living Blues, "We were the first ones to go there with a band." In November or December 1948, Young and Williams recorded for Scales' tiny Planet label; they were joined on the session by harmonica player Snooky Pryor. Scales' recordings were snapped up in 1949 by Egmont Sonderling and Al Benson's Old Swing-Master operation.

Young subsequently made one session for Joe Brown’s JOB label, but Brown chose not to issue the sides, which encouraged Young—already dispirited about the music business—to retire from performing. (The session was done at an unknown date, and the masters may not have been preserved, as they have eluded every reissue program.) With the emergence of white fan interest in blues in the early 1960s, Young was lured out of retirement in 1963, and recorded—we may fairly say, overrecorded—for Testament, Arhoolie, Milestone, Vanguard, Blues on Blues, Spivey, Bluesway, Rounder, and a variety of European labels. Man Young died on April 18, 1974 in Chicago.

Johnny Williams appeared on just one further recording session; he shared studio time with Arthur "Big Boy" Spires, for Chance Records on January 17, 1953. Williams’ two items were not released until the late 1970s, when P-Vine Special in Japan and Charly in the UK put out "Silver Haired Woman" and "Fat Mouth." He stopped performing blues in 1959 after a conversion experience and entered the Baptist ministry, but reappeared on the scene in 1968 when he attended Little Walter’s funeral. Johnny Williams died in Chicago on March 6, 2006.

Johnny Young and Johnny Williams Sources: Jim O’Neal, "Johnny Young" [obit], Living Blues 17 (Summer 1974): 6; Sandy Sutherland, "Uncle Johnny Williams," Blues Unlimited 99 (Feb-Mar 1973): 7-9; John Anthony Brisbin, "Uncle Johnny Williams: Being Regular with the People," Living Blues 127 (May/June 1996): 28-41; Justin O’Brien, "The Dark Road of Floyd Jones, Part I" Living Blues 58 (Winter 1983): 13; Obituary of Johnny Williams in the Chicago Sun-Times, May 11, 2006.

Guitarist Jimmy Rogers was born James A. Lane on June 3, 1924, in Ruleville, Mississippi. He began performing on harmonica. Shortly after arriving in Chicago in 1945, Rogers began working with Muddy Waters and then Little Walter, then all three together as the Headhunters. Since Walter was dominant on harmonica, Rogers switched to rhythm guitar to play with the group. Rogers first recorded for Mayo Williams' Harlem label in 1946—on harmonica—but the one side featuring him was mislabeled on release, inexplicably credited to Memphis Slim and Sunnyland Slim, neither of whom was on that session. His next recording opportunity, on guitar, was with Little Walter for Ora Nelle, but the side was not released at the time.

Jimmy Rogers (eg, voc); Little Walter (hca).

Maxwell Radio and Record Company, Chicago, 1947

| tk. 1 | Little Store Blues (Rogers) | Barrelhouse BH-004, St. George STG-1001, P-Vine [J] PCD-1888, P Vine Special [J] PLP-6714, Shanachie 6801 [DVD/CD] | |

| tk. 2 | Little Store Blues (Rogers) | Barrelhouse BH-004, St. George STG-1001, P-Vine [J] PCD-1888, P Vine Special [J] PLP-6714 |

Take 1 of "Little Store Blues" was included in the CD that accompanied Shanachie's 2008 DVD release, And This Is Free: The Life and Times of Chicago's Legendary Maxwell Street.

Rogers must have been feeling snakebit during this period. His next recording opportunity, for Tempo-Tone in 1949, also failed to generate a release. His two sides for JOB, also in 1949, were dealt to Apollo— then not released till years later. The same happened with his single side, done at the end of a Memphis Minnie session, for Parkway early in 1950. Jimmy Rogers finally broke through in July 1950, when Chess recorded him as a leader after a Muddy Waters session.

Boll Weevil (g, voc).

Maxwell Radio and Record Company, Chicago, 1947

| Christmas Time Blues | Barrelhouse BH-004, St. George STG-1001, P-Vine [J] PCD-1888, P Vine Special [J] PLP-6714, Shanachie 6801 [CD/DVD] | ||

| Thinkin' Blues | Barrelhouse BH-004, St. George STG-1001, P-Vine [J] PCD-1888, P Vine Special [J] PLP-6714 |

"Christmas Time Blues" was also included in the CD that accompanied Shanachie's 2008 DVD release, And This Is Free: The Life and Times of Chicago's Legendary Maxwell Street.

Boll Weevil, a country blues guitarist who often played around Maxwell Street, was almost certainly named Willie McNeal. Two sides with a trio, recorded for in 1955 Club 51 but not released on that label, complete his known output.

Country blues guitarist Sleepy John Estes was born John Adam Estes in Ripley, Tennessee, on January 25, 1899. He recorded for Victor in Memphis on several occasions in 1929 and 1930. After the recording industry rebounded from near-extinction during the Depression, he resurfaced in 1935, recording for Decca in Chicago, subsequently recording for the same company in New York in 1937 and 1938, and again in Chicago in 1940. His last session before the AFM ban took place in Chicago in 1941; it was done for Bluebird. In 1947 (or even a year or two later), he was looking for a new record deal—which, as it turned out, was not imminent. The Ora Nelle sides were done with pretty typical accompaniment—harmonica and one-string bass—but the harmonica player, in George Paulus' judgment, doesn't sound like Estes' long-time musical partner, Hammie Nixon.

Sleepy John Estes (g, voc); uinidentified (hca); unidentified (one-string bass).

Maxwell Radio and Record Company, Chicago, 1947 (?)

| Harlem Bound | Barrelhouse BH-004, St. George STG-1001, P-Vine [J] PCD-1888, P Vine Special [J] PLP-6714 | ||

| Stone Blind | Barrelhouse BH-004, St. George STG-1001, P-Vine [J] PCD-1888, P Vine Special [J] PLP-6714 |

After four sides in 1952, for Sun in Memphis, Estes was off the recording scene until he cut The Legend of Sleepy John Estes for Delmark. From 1964 through 1968, he appeared on several LPs for Delmark, Vanguard, Storyville, and other labels. He made several more between 1972 and 1976, for such labels as Albatros, I Dischi del Sole, and Trio—the names are indicative of international interest in his work. Sleepy John Estes died on June 5, 1977, in Brownsville, Tennessee.

Johnny Temple, another veteran bluesman, was born in Canton, Mississippi, on October 18, 1906. Temple first recorded in 1935, when he cut 6 sides featuring just his guitar and vocals, in Chicago for Vocalion. From 1936 through 1941, he recorded prolifically for Decca, both in Chicago and in New York, generally fronting jazz-oriented combos such as the Harlem Hamfats. In 1941, he cut one session for Bluebird in Chicago, with just guitar and piano backing. J. Mayo Williams knew Temple from the days when Williams ran Decca's race division; in 1946 he recorded a bunch of Johnny Temple sides (intended for his own Harlem/Chicago/Southern/Ebony operation, they ended up being dealt to King Records, which released two of them). The King sides were done with a jazz combo. Temple's one side for Ora Nelle was very different. Unfortunately, "Olds 98 Blues," a remarkable precursor to rock and roll, would not see release until after his death.

Johnnie Temple (eg, voc).

Maxwell Radio and Record Company, Chicago, 1947

| Olds "98" Blues | Barrelhouse BH-004, St. George STG-1001, P-Vine [J] PCD-1888, P Vine Special [J] PLP-6714 |

Here is another contender for the notional honor of first rock and roll record—two years before "Trouble in My Home." And four years before "Rocket 88," which maybe not coincidentally also refers to an Oldsmobile.

Johnny Temple recorded two more sides for Mayo Williams in 1950, this time with a more contemporary blues band. Williams was winding down his record company at the time (he would restart it in 1952), so he dealt these sides to Miracle, which unfortunately was then on its last legs and could not promote them. Temple supposedly cut two more for Chess in 1950, but if this is so no documentation of them remains. He died in Jackson, Mississippi, on November 22, 1968.

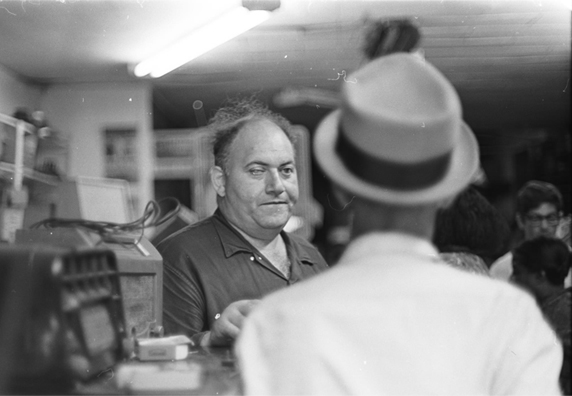

In 1975, when Jim O'Neal and Amy van Singel took the photos that can be seen here, Maxwell Record and Radio was still in operation, untidier and more dilapidated than ever. In 1976, the store moved down the block to 805 West Maxwell. We do not know the exact year that the 805 store closed, but by the early 1990s, the building at 831 Maxwell Street was in ruins. While vacationing in Scottsdale, Arizona, Bernard Abrams died on December 14, 1997, at the age of 78; he was remembered in the blues press. (See Bernard Abrams' obituary, by Tony Burke, in Blues & Rhythm #126. We are indebted to Byron Foulger for a clipping.)

Lamentably, nothing remains today from the market area; what was left of the buildings along that entire stretch was demolished in 1994 to make way for an expansion of the University of Illinois Chicago. Today the former 831 Maxwell Street is just a grassy plot by the sidewalk, part of the UIC athletic fields.

Our thanks to Jim O'Neal and Amy van Singel, for permission to use their photos of 831 Maxwell Street.

Click here to return to the Red Saunders Research Foundation page.

Click here to return to Robert L. Campbell's Home page.