Revision note:We've corrected an error in the personnel of the Four Tons of Rhythm; our thanks to Marv Goldberg for catching it. With new information in hand about Dike-Polzin, a company in Pasadena, California that did metal parts for The Bishop Presses, located in South Pasadena, we've updated our listings on Sessions that were pressed in 1946 and 1947.

We strongly recommend Patrice Hickox's site, Session Sounds, to everyone who is interested in Phil Featheringill and Session Records.

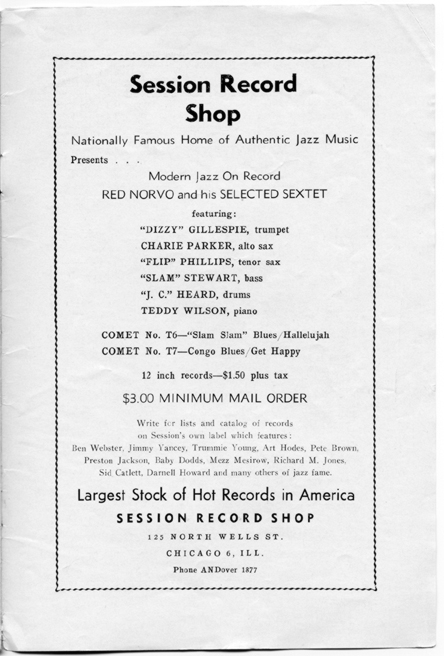

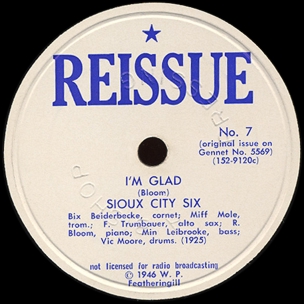

Session was a small label that catered to specialist record buyers. During the label's active period, its co-owners were said in publicity releases to be W. P. "Phil" Featheringill and David W. Bell. Some questions remain as to who controlled what, but Featheringill was definitely the more visible of the two during the label's lifetime.

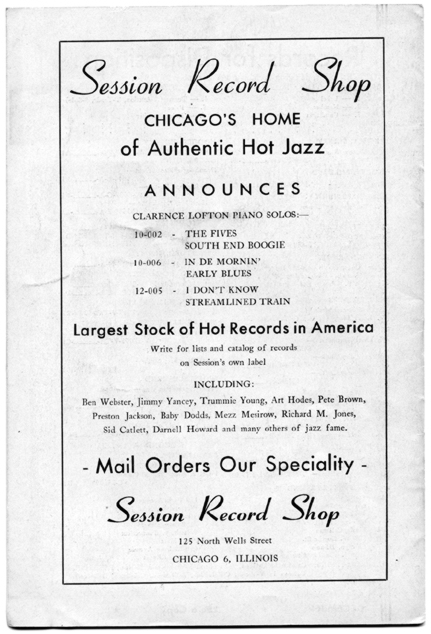

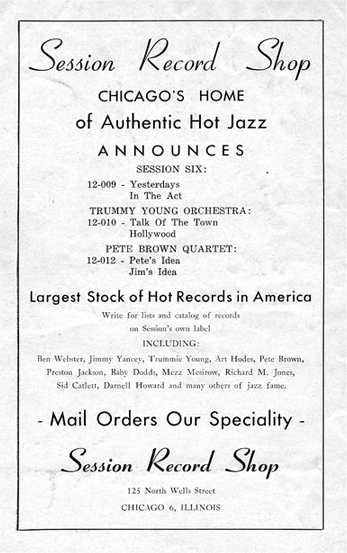

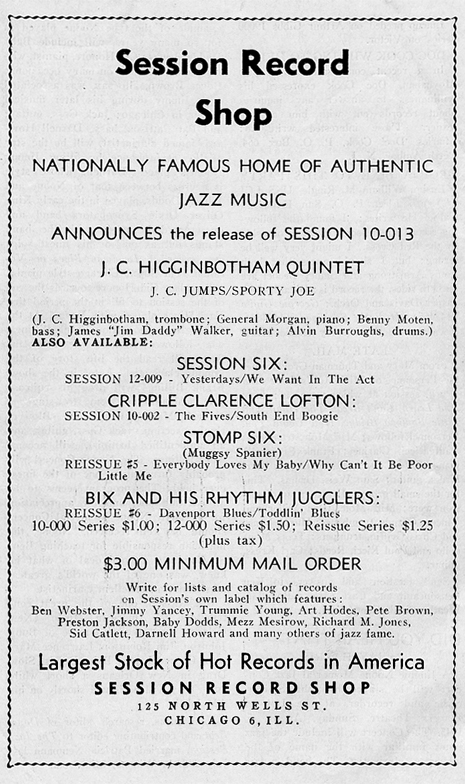

The label ran in conjunction with the Session Record Shop, operated by Phil Featheringill and his wife Evie at 125 North Wells Street in Chicago. The store's specialty, as advertised in the September 1945 Chicago telephone book, was "Original & Re-release Hot Jazz Records." Shop and label both opened for business on November 20, 1943, according to coverage in Down Beat. In his column "The Hot Box" (December 1, 1943, p. 13), George Hoefer, Jr. noted that the shop "will deal exclusively with hot jazz recordings with equal emphasis on the current crop from such sources as the Commodore, Jazz Man, etc. and the rare out of print classics."

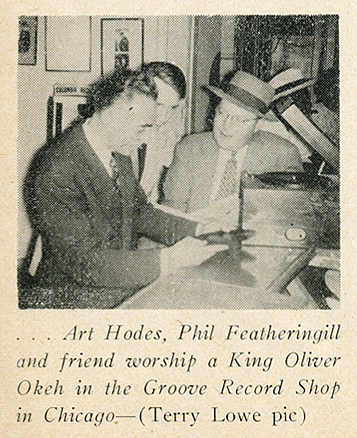

As Hoefer noted, Phil Featheringill previously worked at The Groove Record Shop at 4712 South Parkway on the South Side, where he had been running regular auctions of out-of-print jazz records.

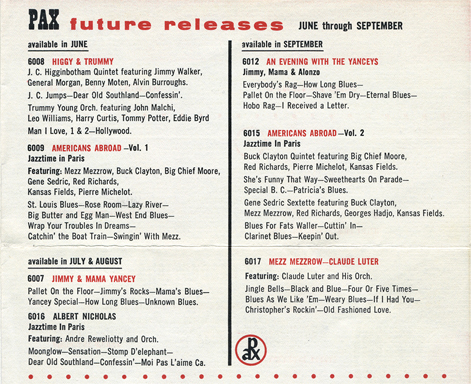

Although the label announced its intention of making "original" recordings when it was launched, Session's first releases were reissues. The targets for reissue were records made in Chicago or by artists with Chicago associations in the first half of the 1920s. (See the Appendix for complete details on the reissues.) By this point in history, many 78s from this period had been long out of print and were becoming increasingly difficult for collectors to find. More substantial reissue programs had already been mounted in the late 1930s by United Jazz Clubs of America and the Hot Record Society. The major labels (at this date, these were Columbia, RCA Victor, and Decca) had also begun reissuing jazz classics whose rights they controlled. However the recording ban of August 1, 1942 stopped new instrumental recording at the majors and the wartime shortage of shellac discouraged reissue activity as well. As an extreme specialist operation, Session focused on the product of tiny Chicago-based companies like Autograph and Rialto, which had put out important material by King Oliver and Jelly Roll Morton during the acoustic era; a ragtime piano solo by Ezra Howlett Shelton was put to use as a flip side for a Jelly Roll Morton solo that originally appeared with a coupling of no jazz interest. (One more Morton 78 reissue derived from Autograph was delayed until 1946, when it appeared on Reissue 8.) These Autograph/Rialto originals were so obscure that some were not listed in Delaunay's Hot Discographybefore Session reissued them.

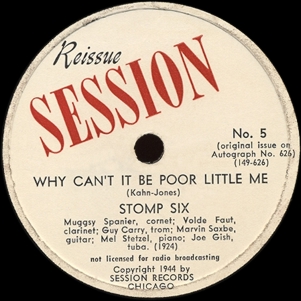

The company also put out three 78s of material that had been recorded for the larger Gennett label; the artists were two groups led by Bix Beiderbecke and the Stomp Six, a combo that featured Muggsy Spanier as lead cornetist. The first three Session reissue 78s (and possibly others done before Featheringill moved his record company to California in 1946) were actually pressed by Gennett. While Gennett had quit making commercial recordings a decade earlier, the parent firm, the Starr Piano Company of Richmond, Indiana, and its pressing plant were still functioning in the 1940s.

Phil Featheringill began recording new material in the fall of 1943, when he took portable equipment to a house party where ragtime pianist Alonzo Yancey was playing. He went to work in earnest recording new material in December 1943, laying down over 30 blues piano sides with Alonzo's more famous brother Jimmy and Cripple Clarence Lofton, plus an extremely obscure figure named Jesse Young.

In fact, the career of the label divides into two distinct periods. Nearly half of the total sides recorded by Session came from the piano marathon of December 1943. A peek at our discographical listings will quickly show how reissue interest has centered on the piano records. Since 1953, these have been kept in near-continuous circulation by labels that cater to fans of boogie-woogie and blues piano.

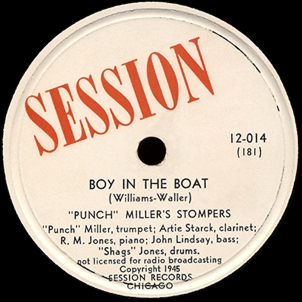

A second wave of recording began February 1944. Now the focus was on jazz combos, some strictly traditional (Richard M. Jones' Jazzmen, Punch Miller and His Southside Stompers, Art Hodes' Trio), some playing fairly advanced Swing (Trummy Young, Ben Webster, Pete Brown, John Levy and Jimmy Jones), some a little harder to categorize (J. C. Higginbotham). The combo recording activities spread out over 8 months, winding down in September 1944. These sides have drawn far less reissue interest: two of the Pete Browns waited over 50 years for a reappearance, and some of the other Swing sides have never been reissued at all.

Phil Featheringill relocated to the West Coast in the summer of 1946, taking the record company's operations with him. Then the Session Record Shop closed down in the Fall of 1946. Featheringill re-pressed many of the Sessions and made them available from a mail-order house and a record distributor that he operated in the Los Angeles area, but this final burst of activity ended in the Fall of 1947.

While most of Chicago's small indies concentrated on local musicians, Session reached out to such nationally known acts as Ben Webster and Sid Catlett to augment its stable of home-grown and locally working artists. The Yanceys and Cripple Clarence Lofton were Chicago residents, as were Richard M. Jones and Punch Miller. Though Art Hodes was a longtime resident of Chicago, and Mezz Mezzrow was a native, neither was based there when Session recorded them. Some of the Swing players were established musicians with national reputations who happened to be working gigs in Chicago: Pete Brown, Trummy Young, and J. C. Higginbotham (the last of whom was working with Henry "Red Allen" at a two-year engagement in a Loop club). A group variously billed as the Chicago Jazzmen or the Session Six included local Swing players (Jesse Miller, Eddie Johnson, and Nat Jones) who were not name artists. Jimmy Jones and John Levy, who participated on that date and later recorded as a duet, were local musicians on their way to national prominence with Stuff Smith's trio. In addition, one trad session (Art Hodes / Mezz Mezzrow) and one Swing session (Ben Webster / Sid Catlett) were conducted in New York City.

Because Session recorded jazz musicians with national prominence and Phil Featheringill, who was the Chicago correspondent for Metronome and was tight with traditional jazz advocate George Hoefer, Jr. at Down Beat, was plugged into the jazz journalism of the day, the company's offerings got unusual attention from the jazz press. We are, after all, talking about an outfit with low pressing runs, limited distribution, and high retail prices for some of its product.

The label was so small that for nearly three years its address was the Session Record Shop (replaced, after the shop closed, by the address of the mail-order operation that Featheringill operated in the Los Angeles area). As for the matter of price, the 3-disk set This Is Jimmy Yancey (Session Set 1), which consisted of the first three Jimmy Yancey 12-inch releases on Vinylite, went for $8.50. This was a substantial sum in 1944, roughly what a classical maven had to cough up for an entire Beethoven symphony on 78s. (The company's subsequent retreat to conventional pressings brought its retail prices in line with what the competition was charging.) Moreover, the acrimony between the Moldy Figs and the Moderns was going full tilt when Session began doing combo recordings. On the Modernist side, Metronome's record reviews, which were written by Barry Ulanov and Leonard Feather, vented their fervid dislike of traditional jazz: they faulted the Session combo records for sound quality, musical interest, or both. Meanwhile Down Beat, where George Hoefer, Jr., played a prominent role, worked hard to promote Session's products. Smaller publications for old-jazz enthusiasts and record collectors also gave Session 78s a positive reception.

An unusual feature of Session's efforts was its reliance on 12-inch 78s, which took up half of the company's new releases. 12-inch records offered the advantage of longer playing times (all the way to 5 minutes, as opposed to the 3 or 3 1/2 minutes on the standard 10-inch record). But they were more expensive, and the industry reserved them mostly for classical recordings. According to Geoffrey Wheeler, in his 1999 book Jazz by Mail, distributors and retailers disliked 12-inch records because they broke more easily. A few other small jazz labels were putting out 12-inch records at the time: Commodore, HRS, General, Black & White, Comet, and Blue Note (in its early days). Session went so far as to press the first run of 12-001 through 12-003 on Vinylite. This put them in the forefront technologically, required no scarce shellac, and cut significantly down on breakage—but jacked up the cost. For their subsequent 12-inch offerings (including later pressings of the first three), Session reverted to conventional shellac and ground limestone, which they used throughout for their 10-inch releases. By going back to shellac they reduced their pressing costs, but reintroduced the breakage issue. A couple of other indie labels with jazz interests, American Music and Black & White, would soon have the same experience of releasing 12-inch 78s on Vinylite, finding it too expensive to sustain, and reverting to shellac, with the expected negative reactions from many jazz record stores.

The first six numbers in the Session matrix series (100 through 105) were used for Reissue Session 1 through 3 (see our Reissue listing at the end of the page).

The first new sides recorded for the label, though not the first to be released, were the work of Alonzo Yancey, a ragtime pianist and brother of the much more famous Jimmy. These have been listed as studio recordings in the past. We know that Phil Featheringill recorded Alonzo at a house party, at some point in the fall of 1943, and we strongly suspect that at least one of Alonzo's sides as issued on Session came from that source; what we don't know is whether some of the others were recorded in the studio in December 1943, as discographies have previously stated.

We also don't know the actual order of recording for the solo piano items on Session, so we will be grouping them by artist, starting with Alonzo Yancey.

Alonzo Yancey (p).

Chicago, prob. Fall 1943

| PF-31-B (60-B) | Unknown Rag | Wayhi L93 [cassette], Document BDCD 6045 | |

| PF-32-A (61) | Ecstatic Rag | Wayhi L93 [cassette], Document BDCD 6045 | |

| PF-32-B (62) | Everybody's Rag | Wayhi L93 [cassette], Document BDCD 6045 | |

| WC-106 DP | Everybody's Rag | Session 10-015, Pax LP6012, Jazztone J-1023, Guilde du Jazz J.1023, Origin of Jazz Library OJL16, Biograph BLP-12047, Gannet GEN5138, Storyville SLP238, Document DOCD-5043 | |

| WC-107 DP | Twelfth St. Rag | Session 10-015, Gannet GEN5138, Storyville SLP238, Document DOCD-5043 | |

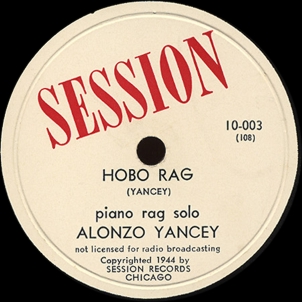

| WC-108 DP | Hobo Rag (Yancey) | Session 10-003, Pax LP6012, Gannet GEN5138, Storyville SLP238, Document DOCD-5043 | |

| 109 | Ecstatic Rag | unissued | |

| 110 | Ecstatic Rag | unissued | |

| WC-124 DP | Ecstatic Rag (Yancey) | Session 10-003, Gannet GEN5138, Storyville SLP239, Document DOCD-5043 |

In his column "The Hot Box" (Down Beat, August 1, 1944, p. 11), George Hoefer, Jr., had an announcement to make:

Also scheduled for release soon are some interesting piano rags by Jimmy Yancey's brother, Alonzo, who passed away a month after cutting the sides. Alonzo had never played other than at house parties prior to April 1944. He composed many rags and stomps, one of which he made at this session. This number is Ecstatic Rag, which will be paired with Hobo Rag on Session 10-003. The two other sides, Everybody's Rag and 12th St. Rag will be assigned a number later. Alonzo Yancey was a friend and companion at house parties with Clarence Lofton and his brother, Jimmy.

We don't buy the April 1944 date that Hoefer mentions. According to Godrich, Dixon, and Rye (4th edition), Alonzo was recorded at a party in the fall of 1943. And the PF prefixes to the numbers that were written on the original acetates of the first three items on this entry point to someone we know. In 1990, the masters of these party recordings of Alonzo Yancey were auctioned off, and three of the sides were finally issued, first on a Wayhi cassette in 1993, then later that year on a Document CD. There may be additional unissued acetates from this source.

Other discographies have given December 1943 as the recording date for matrix numbers 106-110 and 124. But complicating matters is the fact that matrix 107, "Hobo Rag," is incomplete (just 1:45 as issued, and missing its opening). Were some of the items that ended up with 100-series Session matrix numbers also recorded on portable equipment at a house party?

Session 10-003 and 10-015 were 10-inch 78s. 10-003 is copyrighted 1944 and presumably exists in an earlier version with an F prefix to the matrix numbers. However, the copies we are aware of were manufactured in 1946 by The Bishop Presses, of South Pasadena, California; the matrix numbers are incised, but have the WC prefix (for West Coast). After the matrix number there is a monogram, which we can't reproduce accurately in our listing, of a D with a P stuck in it. This, we recently learned, stood for Dike-Polzin Record Processing, 221 South Arroyo Parkway, Pasadena, California. Dike-Polzin (by 1950 it had changed its name to Deeco) did the masters and mothers for most of the records that Bishop pressed.

Session 10-015 was released in early 1947 (it was first advertised in the March 1947 issue of the Record Changer, and reviewed by John Lucas in May). Known copies have a red label, a 1946 copyright date, and incised matrix numbers in the shellac with a WC prefix and another Dike-Polzin monogram after the nubmer. Pressings were by Bishop, a company in South Pasadena, California that Featheringill acquired a financial interest in. He used The Bishop Presses, which opened in April 1946, for all of his later Session pressings. Bishop regularly handled releases for Jump, a small Southern California-based company, and from December 1946 through June 1950 pressed most of John Steiner's S D, Dublin's, and Paramount releases.

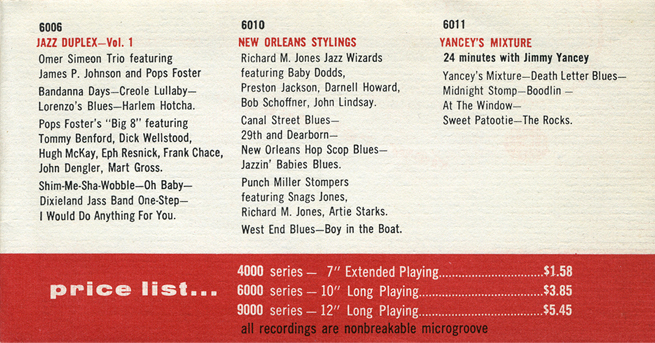

Pax LP6012 was a 10-inch LP titled An Evening with the Yanceys: Jimmy, Mama & Alonzo ; its contents were listed in the Pax Jazz LP catalog of May 1954, where it was scheduled for issue in September 1954--but it never made it.

Jazztone J-1023, a straight repackaging of Pax LP6012 in the 10-inch format, was released in 1957; its counterpart Guilde du Jazz J.1023 was a French LP titled Une soirée avec les Yancey (Jimmy-Mama-Alonzo).

Gannet GEN5138 was a British LP that John Holley issued c. 1975. Titled Jimmy Yancey and Alonzo Yancey Volume 3; it was filled out with Jimmy Yancey's sides for Victor and Bluebird (1939-1940) and Vocalion (1940), as well as two home recordings from 1940.

Storyville SLP238 was a Danish LP titled The Yancey-Lofton Sessions, Volume 1. Storyville SLP239 appeared under the title The Yancey-Lofton Sessions, Vol. 2; both also include material by Jimmy Yancey and Cripple Clarence Lofton.

Biograph BLP12047 was a various-artists collection titled Black and White Ragtime 1921-1939 [sic].

Document DOCD-5043 was released in the 1990s under the title Jimmy Yancey Volume 3: 1943-1950; it is obvious who is responsible for the remainder of the tracks! Document BDCD 6045, Piano Discoveries (1928-1943), released in 1993, was a collection of piano recordings which also included a track by Ezra Howlett Shelton (see the entry Reissue 3, in the Appendix) and items by Jimmy Yancey and Cripple Clarence Lofton (not of Session origin).

Görgen Antonsson (http://sunsite.kth.se/feastlib/mrf/yinyue/pw/YANALO.HTM) claims that Origin of Jazz Library OJL-16, which came out in 1968, actually contained 108 "Hobo Rag" and mistitled it as 106 "Everybody's Rag"—this needs to be checked. According to Antonsson's listing for the label at http://sunsite.kth.se/feastlib/mrf/yinyue/pw/ORIGI.HTM, OJL-16 was titled Ragged Piano Classics and included one track each by Robert Cooper, Herve Duerson, Will Ezell, Blind Leroy Garnett, Sugar Underwood, and Alonzo Yancey, as well as additional performances by "white or jazz artists."

Matrix numbers 111 and 112 remain unaccounted for. Jimmy Yancey's contributions begin with number 113 (see below). So 111 and 112 could have been intended for the mysterious Session 10-004, by one Jesse Young.

Jesse Young (p)

Chicago, 1943

| 111? | Flyin' Santa Fe | Session 10-004[?] | |

| 112? | Skipper | Session 10-004[?] |

Jesse Young was a blues pianist, as one might expect from the titles, and from the focus of the label's recording activities in 1943. But all we have on his sides is a solitary entry in the Esquire Jazz Book for 1945. Leonard Feather's "Discography of the Year" for 1944 (p. 137 in the aforesaid Esquire tome) lists Session 10-004 and identifies the sides as "piano solos." The promised release never materialized.

No Jesse Young is listed in Godrich, Dixon, and Rye, or in any other blues discography. The only other trace we have found of him is a composer credit for "Greyhound Bus," a number recorded by Washboard Sam on August 5, 1940, and issued on Bluebird B-8540-B. (See our Buster Bennett page for details; the pianist on the session was Blind John Davis.) Nor have any of the reissues of the Session piano records included Young's sides. All we can do is hope that the masters have been preserved and that they will see issue one day.

The most extensively documented pianist on the early Session recordings, Jimmy Yancey, was born in Chicago on February 20, 1898. From ages 6 to 17 he worked as a singer and tap dancer in vaudeville. Starting around 1919 he played piano in public and played professional baseball in the Negro Leagues. In 1925 he took what would be his day job for the rest of his life, as a groundskeeper for the Chicago White Sox at Comiskey Park. Jimmy Yancey made his first records in Chicago for Solo Art in 1939. He recorded in Chicago for Victor (also 1939), Vocalion (1940), and Bluebird (1940), and cut two tracks in his home in 1940 that were released years later. In 1941, he suffered a stroke that imposed some limitations on his left-hand technique. He cut several records at private parties in Chicago in the fall of 1943 before undertaking his marathon date for Session.

Again not knowing the order in which they were recorded, we have grouped all of Jimmy Yancey's December 1943 sides together. As far as we know, all were studio recordings. The missing matrix numbers belong to one side by his brother Alonzo (124; already listed in Sess1) and to six by Cripple Clarence Lofton (125 through 130; see Sess4 for these).

Jimmy Yancey (voc -1; p -2; harmonium -3); Estella "Mama" Yancey (voc -4).

prob. Chicago Recording Company, Chicago, December 1943

| WC-113-C | Boodlin' (Yancey) -2 | Session 10-001, Vogue LDE166, Jazztone J-1224, Vogue V2365 [78], Vogue EPV-1203, Jazz Selection JSLP 50.019, Folkways FJ2082, Gannet GEN5136, Jazz Anthology 30JA5212, Storyville SLP238, Document DOCD-5042 | |

| 114 | Yancey's Mixture -2 | Pax LP6011, Jazztone J-1224, Jazztone J-1258, Jazz Selection JSLP 50.019, Vogue LDE166, Gannet GEN5136, POP SPO 17.003 [EP], Jazz Anthology 30JA5212, Storyville SLP238, Document DOCD-5042 | |

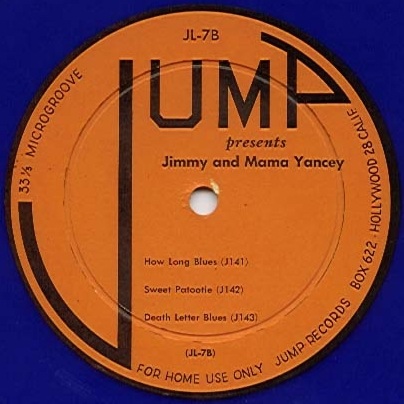

| 115 [J143*] |

Death Letter Blues -1, 2 | Jump JL-7*, Pax LP6011, Jazztone J-1224, Jazz Selection JSLP 50.019, Vogue LDE166, Gannet GEN5136, Jazz Anthology 30JA5212, Storyville SLP238, Document DOCD-5042 | |

| 116 [J142*] |

Sweet Patootie -2 | Jump JL-7*, Pax LP6011, Jazztone J-1224, Vogue EPV-1203, Vogue LDE166, Jazz Selection JSLP 50.019, Gannet GEN5136, Jazz Anthology 30JA5212, Storyville SLP238, Document DOCD-5042 | |

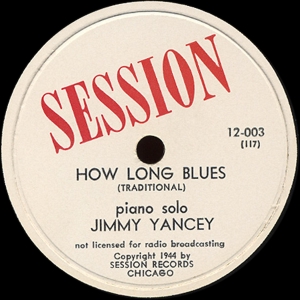

| 117-A; WC-117 B-1811x [J141*?] |

How Long Blues (trad.) -2 | Session 12-003, Folkways FP 55, Jump JL-7* [?], Folkways FJ2802, Folkways FE4602, Gannet GEN5137, Storyville SLP238, Document DOCD-5042 | |

| ? [J141*?] |

How Long Blues (trad.) -2 | Session 12-003, Jump JL-7* [?]. Pax LP6012 [?], Jazztone J-1023, Guilde du Jazz J.1023, Oldie Blues [Nl] OL 2802, Document DOCD-5042 | |

| 118 | The Rocks (Yancey) -2 | Pax LP6011 [LP], Vogue LDE 166 [LP], Vogue V2365 [78], Jazztone J-1224, Vogue EPV-1203, Jazz Selection JSLP 50.019, POP SPO 17.053 [EP], Gannet GEN5136, Jazz Anthology 30JA5212, Storyville SLP238, Document DOCD-5042 | |

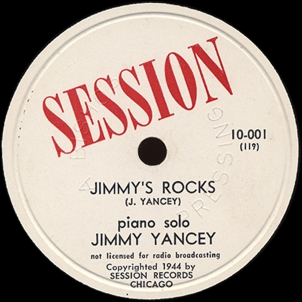

| WC-119 | Jimmy's Rocks (Yancey) -2 | Session 10-001, Oldie Blues [Nl] OL 2802, Gannet GEN5137, Document DOCD-5042 | |

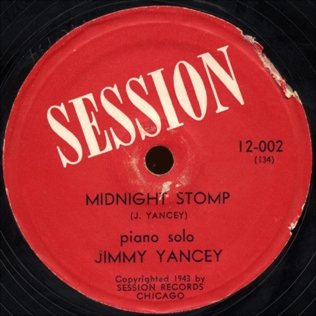

| 120; WC-120 B-1812 | How Long Blues (trad.) -3, 4 | Session 12-002, Pax LP6007, Oldie Blues [Nl] OL 2802, Gannett GEN5137, Roots EPL001, Storyville SLP239, Document DOCD-5042 | |

| 121? | Mama's Blues -2, 4 | Session 12-004 [?], Pax LP6007 [?] | |

| 122? | Rough and Ready | Session 12-004 [?], Pax LP6007 [?] | |

| 123 | White Sox Stomp -2 | Jazztone J-1023, Guilde du Jazz [Fr] J-1023, Oldie Blues [Nl] OL 2802, Gannet GEN5137, Storyville SLP239, Blues Encore CD52031, Document DOCD-5043 | |

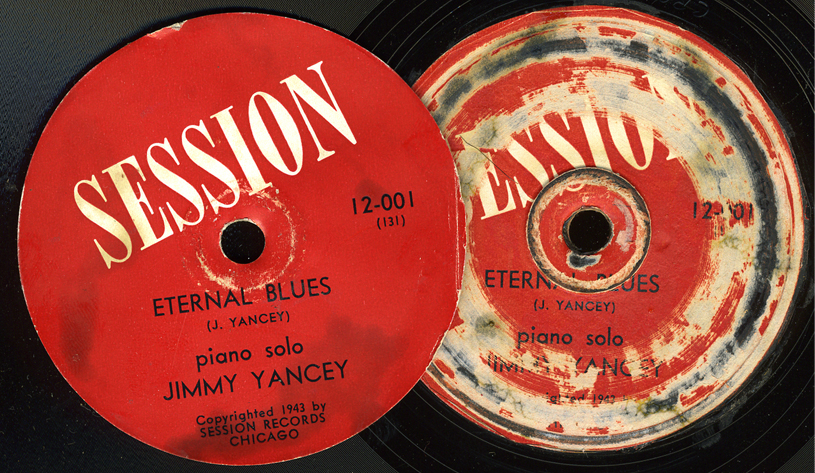

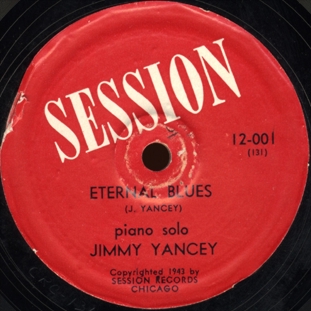

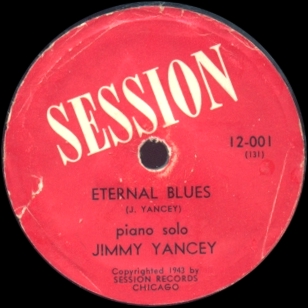

| CRC-131; WC-131 B-1813 | Eternal Blues (Yancey) -2 | Session 12-001, Pax LP6012, Jazztone J-1023, Guilde du Jazz J.1023, Oldie Blues [Nl] OL 2802, Gannet GEN5137, Storyville SLP239, Blues Encore CD52031, Document DOCD-5043 | |

| 132 | I Received a Letter -2 | Pax LP6012, Jazztone J-1023, Guilde du Jazz J.1023, Oldie Blues [Nl] OL 2802, Gannet GEN5137, Storyville SLP238, Document DOCD-5043 | |

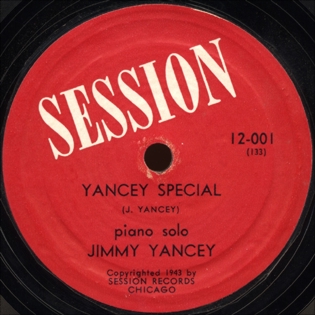

| (133); WC-133 B-1814 [J139*] |

Yancey Special (Yancey) -2 | Session 12-001, Jump JL-7*, Pax LP6012, Jazztone J-1023, Guilde du Jazz J.1023, Oldie Blues OL 2802, Gannet GEN5137, Joker SM 4081, Joker SM 9416, Storyville SLP239, Jazmine JSMCD2538, Document DOCD-5043 | |

| CRC-134; WC-134 B-1815x | Midnight Stomp (Yancey) -2 | Session 12-002, Pax LP6011, Vogue LDE 166, Jazztone J-1224, Gannet GEN5136, Jazz Selection JSLP50.019, Jazz Anthology 30JA5212, Storyville SLP238, Jazmine JSMCD2538, Document DOCD-5043 | |

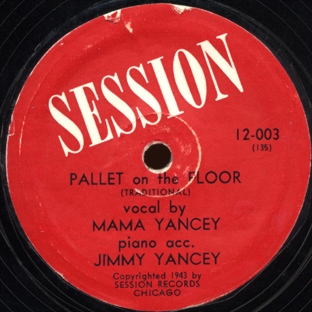

| (135); WC-135 B-1816 | Pallet on the Floor (trad.) -2, 4 | Session 12-003, Pax LP6012, Jazztone J-1023, Guilde du Jazz J.1023, Oldie Blues [Nl] OL 2802, Gannet GEN5137, Storyville SLP239, Blues Encore CD52031, Document DOCD-5043 | |

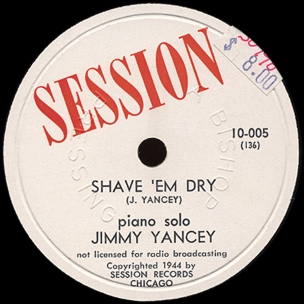

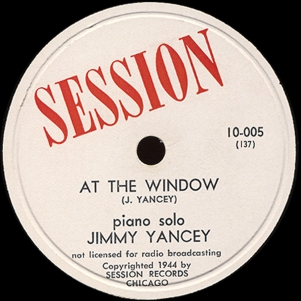

| WC-136 DP [J140*] |

Shave 'em Dry (Yancey) -2 | Session 10-005, Jump JL-7*, Pax LP6012, Jazztone J-1023, Guilde du Jazz J.1023, Oldie Blues [Nl] OL 2802, Gannet GEN5136, Storyville SLP239, Document DOCD-5043 | |

| WC-137 DP | At the Window (Yancey) -2 | Session 10-005, Pax LP6011, Jazztone J1224, Vogue EPV-1203, Vogue LDE166, Jazz Selection JSLP 50.019, Gannet GEN5136, Jazz Anthology 30JA5212, Storyville SLP239, Document DOCD-5043 | |

| 138 [J138*] |

Make Me a Pallet on the Floor (trad.) | Jump JL-7*, Pax LP6007, Gannet GEN5137, Storyville SLP239, Oldie Blues [Nl] OL 2802, Roots EPL001, Document DOCD-5043 | |

| 139 |

There are two versions of the solo piano "How Long Blues." It took nearly 20 years before anyone called attention to this fact in print: in his review of Gannet GEN 5137 and Oldie Blues OL 2802 in Blues Unlimited (August 1974, p. 22), Mike Rowe noted that the LPs used different versions of "How Long." But Rowe, not knowing Session 12-003, called the Gannet version (which had been dubbed from a Session 78) an alternate take, and referred to the version released on a Jazztone LP (and taken up by Oldie Blues) as the original. In fact, 117-A (which appears as WC-117 on later pressings) is the only take of 117 known to to exist; it times in at just under 4 minutes. Discographies have further mixed things up with still a third version of "How Long" (recorded as a vocal with harmonium accompaniment, matrix 120). The 117 version appears on Document CD 5042 as track 16.

The original matrix number for the second solo version of "How Long" (first issued on Jazztone J-1023 and its French counterpart Guilde du Jazz J.1023) remains unknown. This version fades in and, because of the extra-slow tempo, runs 4 1/2 minutes. The Storyville and Document issues give the matrix number as 117, but this was an incorrect surmise (besides which, the Storyville compilers didn't know the real 117); each different version of a tune on the blues piano sessions was given a different matrix number. On Document 5042, this version appears as track 15.

Session 10-001 was a 10-inch release; it appeared in 1944. Known copies of 10-001 have white labels and stamped matrix numbers with a WC prefix, pressed by Bishop.

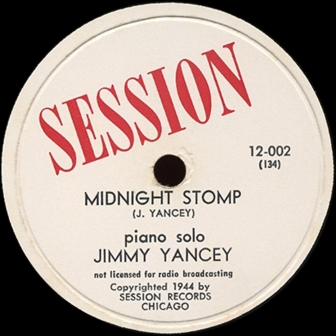

Session 12-001, 12-002, and 12-003 were 12-inch 78 rpm releases; they were initially packaged as Session Set 1, This Is Jimmy Yancey, pressed on Vinylite and sold for the stiff price of $8.50. The red labels on the Vinylite copies have an odd appearance that results from being glued over other red labels that were then sanded down. The apparent source of the trouble was inadequate preparation of the area around the center hole before the labels were glued on. (Pressing on Vinylite really was a brand-new procedure at the time.) The labels carry a 1943 copyright date, and the matrix numbers are incised in the vinyl.

Most extant copies of the Vinylite pressings are made of black vinyl (which has grayed somewhat with age). However, Mama Yancey remembered in a 1964 interview with Barbara Dane and Pete Welding that she and Jimmy had made "LPs" (i.e., 12-inch records) for Session, and that they were pressed on red Vinylite. (Our thanks to Jane Bowers for her transcription of part of the interview.) And sure enough, a red Vinylite copy of 12-001 has turned up at an auction.

The later pressings were done on shellac with neatly applied white labels, a 1944 copyright date, and WC prefixes on stamped matrix numbers. The later pressings of 12-001 through 003 were sold separately.

The Vinylite pressings of Session 12-001 carry CRC-131 incised in the vinyl on one side—and nothing on the other (though 133 can be seen on the label). CRC stands for Chicago Recording Company, a commercial studio that was active in the mid-1940s. CRC also did mastering; it handled some of S D's releases that were pressed in 1944. The shellac pressings have numbers with WC prefixes stamped in the shellac, and B series stamper numbers incised.

The Vinylite pressings of Session 12-002, which are from 1943-1944, carry CRC-134 incised in the vinyl on the "Midnight Stomp" side (120 on the other). The shellac pressings, from 1946 or later, use WC prefixes for the stamped matrix numbers; there is also a stamper number in the B 1800 series (from Bishop) on each side.

"Midnight Stomp" as issued on Session 12-002 consisted of 18 blues choruses. Jimmy Yancey normally did not repeat himself during an improvisation, but chorus 15 and 16 on the original performance are virtually identical. On the Pax LP and the Gannet LP the track is unedited. On Jazztone J-1224, one of the repetitive choruses (either 15 or 16) has been cut; the same is the case on the Document CD.

On the original Vinylite pressings of Session 12-003, the matrix numbers are incised in the vinyl, with no prefixes (in fact the 135 side has no matrix number in the vinyl at all, though there is one on the label.) Later pressings are on shellac, carry white labels and 1944 copyright dates, and have stamped matrix numbers with the WC prefix and incised stamper numbers with the B prefix for Bishop.

On Febuary 15, 1944, George Hoefer Jr.'s column "The Hot Box" announced that the first three Sessions were in the offing, and would be sold as a set for $8.50. "In addition to catching the real Yancey [the Featheringills] discovered that Mama Yancey (Jimmy's wife) can sing very fine blues, and she sings on two of the sides."

On May 15, 1944, Down Beat followed up with an ecstatic review (p. 8) of "Session Set 1," This Is Jimmy Yancey. The review was by "Jax" (John Lucas, a trad jazz proponent who was located in Chicago and was obviously in close touch with Featheringill). As Jax opined, "the Featheringills have caught the true spirit of Jimmy Yancey and his wonderful wife Estella. Yancey Special gives Jimmy plenty of opportunity to exercise his famous boogie abilities at a medium tempo, and he comes through with a performance that completely outclasses the fine rendition by Meade Lux Lewis." The 5 remaining performances received comparably glowing commentary. And Lucas had no complaints about the extra expense: "Pressed in Vinylite, the first commercial use of this flexible and unbreakable material, this limited edition possesses amazing fidelity." In Down Beat for January 1, 1945, Session 12-001, "Eternal Blues" b/w "Yancey Special" was one of 3 Session releases to make "Mix"'s top 10 list for "Piano Discs" ("Best Hot Discs of 1944," p. 11).

Another laudatory review of the set was contributed by Master Sergeant George Avakian. Duly noting the steep price, Avakian wrote "I think I'd cheerfully cough up the major portion of a sawbuck just for Eternal Blues and Make Me a Pallet on the Floor..." (The Jazz Record, September 1944, p. 3). But Avakian was already a fervent admirer of Vinylite (which was being used, noncommercially, for V-Disks produced for the entertainment of the armed forces). He had once owned a Benny Goodman 78 experimentally manufactured out of the substance; he would entertain guests by dropping it on the floor and slamming it against the wall before playing it. As for the music on the set, "It is, quite distinctly, the feline's mustaches. Jimmy's piano should be known to all jazz fans, and for the first time we hear his wife, Estella, known as Mama—and a worthy successor to the great traditional blues singers she is" (p. 13). Avakian prefers her contribution on Pallet on the Floor to her singing on the vocal version of How Long ("Jimmy plays organ on this side (apparently of the home-grown, foot-pedal variety)"). Out of the instrumental sides, Avakian singles out Eternal Blues. Of the instrumental How Long he says, "very slow, deliberate, and delicately simple." He describes Yancey Special as "the weak side of the date, which is merely praise for the rest of the session. You know the tune from the Meade Lux recording; it's also a standard testing piece for all your neighbors who try to learn boogie woogie on their pianos."

Before Session 12-001 through 12-003 were re-pressed on shellac, there was an extended period, at least 2 years, of unavailability (the press runs for the Vinylite versions had to be minuscule).

Session 10-005 was a 10-inch 78 made in extremely limited quantities. We know of just three copies: one in Konrad Nowakowski's collection, one in the SONIC database, and one in the collection of the late John Steiner (who played it in 1999 on a BBC Radio 3 program that presented a portrait of Jimmy Yancey).

Session 10-005 was first advertised in a Records, Inc. ad in the Record Changer for March 1947 and reviewed in the May issue. The copy in our hands was pressed by Bishop (in 1947) and has WC prefixes in the shellac; as with the copies of Session 10-003 that we have seen, the matrix numbers are stamped instead of incised and are followed by the Dike-Polzin monogram. Was there an earlier pressing of 10-005 with the F prefix? Collectors, what say you?

In his article on Jimmy Yancey's recordings for Record Research, Walter C. Allen declared that "only a few copies were pressed gratis for friends" (Volume 2, no. 1 issue 7, February 1956, p. 5). His source was George Hoefer's liner notes for Pax LP 6011, which were apparently referring to a 1944 test pressing.

Session 12-004 was announced but apparently never issued; hence the matrix numbers are not known. However, George Hoefer, Jr. mentioned 12-004 again in the discography attached to his 1951 Down Beat obituary article for Jimmy Yancey, so he must have heard a test pressing! At least one side of 12-004 was scheduled for release on Pax LP6007 (maybe there was a jinx in operation, for that LP never came out either). There are suggestive gaps in the matrix series at 121 and 122 and again at 139.

The first reissue of an Session material was a 10-inch LP on Folkways FP 55, a various-artists compilation called Jazz, Vol. 2: The Blues. Though copyrighted 1950, it probably came out in 1951 (it was reviewed in the Record Changer, June 1951 issue, pp. 15 and 18). The use of the Session material may have been unauthorized; another LP in the same series led to a lawsuit by Marili Ertegun of Jazz Man and Rudi Blesh of Circle, who charged that Folkways was bootlegging their material. Folkways FJ 2802 was a straight reissue of FP 55, and we assume that FE4602 did likewise, though it would be nice to be able to confirm this. The Folkways issues incorrectly identify "How Long" as coming from Session 12-002 (that would be matrix 120), instead of Session 12-003 (matrix 117).

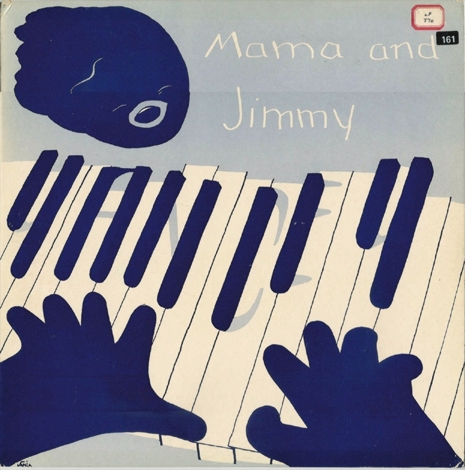

Next came Jump JL-7, a 10-inch LP of Jimmy Yancey material put out by Ed Kocher and Clive Acker, whose record sales and distribution enterprises Phil Featheringill worked for after his move to the West Coast in 1946. It was released in 1953. (Tom Lord's Jazz Discography, Volume 26, manages to mention one of the tracks that appeared on Jump JL7: 138, "Make Me a Pallet on the Floor.")

Pax LP6011, said to be available in the Pax catalog for May 1954, but actually issued in December of that year, was titled Yancey's Mixture: 24 Minutes with Jimmy Yancey. Pax LP 6012, intended to be issued in September, was to be titled An Evening with the Yanceys: Jimmy, Mama, & Alonzo. Pax LP6007, Jimmy & Mama Yancey, was announced for release in July or August of 1954, but never materialized either.

Vogue L.D.E. 166, a 10-inch LP titled Jazz Immortals No. 2 Jimmy Yancey-Piano Solo was listed among the latest releases in Jazz Journal for February 1956.

Vogue EPV-1203 was a British EP that consisted of the B side of Pax LP6011, in a different order; it was released in March 1957 and reviewed in Jazz Journal's July 1957 issue (p. 20).

Jazz Selection J.S.L.P. 50.019 Jazz Immortals no. 1: Yancey's Mixture is a straight reissue of Pax LP6011 done by French Vogue; the master numbers on each side are the same as on the Pax.

POP SPO 17.053, abc du jazz - i: Piano Traditionnel is an EP made by French Vogue, perhaps at a later date. The other 3 titles are from other sources. "The Rocks" cames out correct on the cover but is misspelled "the roks" on the label.

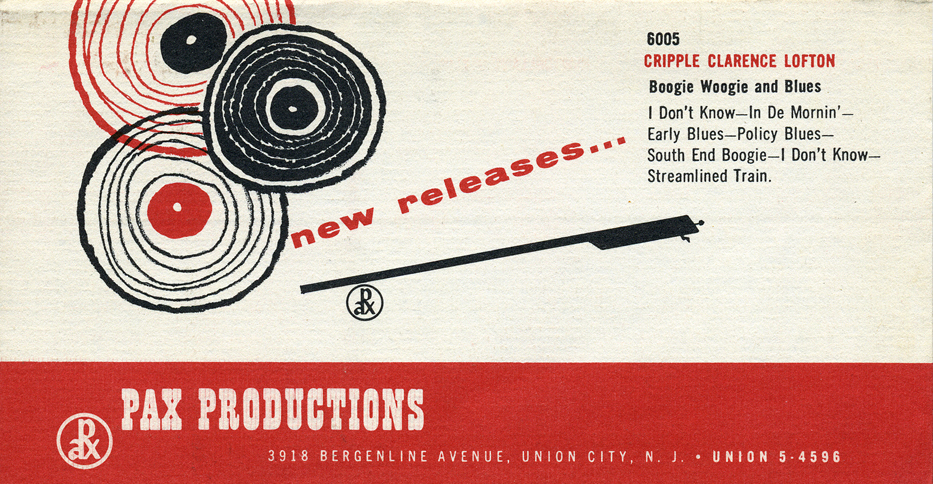

Jazztone J-1224, Pioneers of Boogie Woogie: Jimmy Yancey and Cripple Clarence Lofton was a 12-inch LP that incorporated material from two issued 10-inch Pax LPs, 6005 and 6011. The Yancey side is identical to Pax LP6011, tracks in the same order as they appeared on Side A then Side B—except that "Midnight Stomp" has been discreetly edited (see above). The Jazztone LP appeared in March 1956, according to Geoffrey Wheeler, Jazz by Mail (published 1999, pp. 112-113). Jazztone J-1258 was 12-inch LP sampler that included one Jimmy Yancey track from J-1224; it was released in March 1947, according to Geoffrey Wheeler's book Jazz by Mail (1999, p. 144). Jazztone J-1023 was a 10-inch LP issued in 1957; its French counterpart, Guilde du Jazz J.1023, was titled Une Soiréee avec les Yancey (Jimmy-Mama-Alonzo). J-1023 was unusual in the Jazztone line in that it was issued only in Europe, not in the USA.

Oldie Blues OL 2802, The Immortal Jimmy Yancey 1898-1951, released in the Netherlands 1974, was a reissue of Jazztone J-1023 with two 1940 tracks by Jimmy Yancey added and one track by Alonzo Yancey deleted.

Gannet GEN5136 and 5137 were British LPs released in 1974 as Jimmy Yancey/Cripple Clarence Lofton Volume 1 and Volume 2.

Jazz Anthology 30JA5212 belonged to a big series of cheap reissue LPs put out by the French company Musidisc in the mid to late 1970s. We are assuming that it drew from the previous releases on Jazztone and Vogue but it would be nice to have confirmation on that.

Storyville SLP238 was a Danish release titled The Yancey-Lofton Sessions, Vol. 1. On SLP238, the track titled "Sweet Patootie" is actually "Boodlin'," which therefore appears twice on the LP (oops!). Storyville SLP239 was a Danish release, The Yancey-Lofton Sessions, Vol. 2.

Jazzmine JSMCD2538 is a British various artists compilation on CD titled Boogie Woogie Volume 1—Piano Soloists.

Document DOCD 5042 is an Austrian CD released in 1991 under the title Jimmy Yancey Volume 2. The continuation on DOCD 5043 goes as Jimmy Yancey Volume 3: 1943-1950; this CD follows Jazztone J-1224 in using the edited version of 134, "Midnight Stomp."

After making these sides for Session, Jimmy Yancey, though musically active, was off the recording scene for several years. George Hoefer Jr.'s column "The Hot Box" (Down Beat, January 28, 1946, p. 17) noted that "Gene Keasler, Chicago Times sportswriter, recently did column Boogie Woogie On The Diamond featuring Jimmy Yancey who helps take care of the White Sox ball park. Jimmy's record of Pallet On The Floor is called Pile It on the Floor. Also announces Jimmy and Mama are working on a new tune to be called Weekly Blues. Jimmy Yancey performed at Carnegie Hall with Mama Yancey in 1948, and worked regularly at the Bee Hive in Chicago from 1948 through 1950, when it featured traditional jazz instead of the bebop for which it became known later. In December 1950, Jimmy Yancey made a session at the Myron Bachman studio; it was sold to John Steiner and appeared on a 10-inch LP on his revival of the Paramount label. Steiner liked the material so much he pretended to have recorded it. In 1951 Jimmy Yancey recorded an album's worth of material for Atlantic (his last studio session) and participated in several private sessions that were later released on Document. Jimmy Yancey died in Chicago on September 17, 1951. (For biographical information see J. Bradford Robinson and Barry Kernfeld, "Jimmy Yancey," in B. Kernfeld (Ed)., New Grove Dictionary of Jazz (2nd edition, Volume 3), pp. 1002-1003 (New York: Grove's Dictionaries, 2002).

The other major contributor in the early going, Cripple Clarence Lofton, was born on March 28, 1887 in Kingsport, Tennessee. His physical impairment, a birth defect to one leg that gave him a pronounced limp, wasn't serious enough to prevent him either from tap dancing or from playing the piano while standing up. A leading exponent of boogie woogie, he developed a high energy act during years spent working tent shows. In the 1930s, he ran his own club, the Big Apple, in Chicago. Lofton began recording in Chicago in 1935 (sessions for Vocalion and the American Record Company, as well as one side for Bluebird as "Albert Clemens"). In 1938 or 1939, he appeared on a private recording session whose contents were issued on LP in the 1960s and 1970s by Swaggie, Yazoo, and Mauros. In 1939 Lofton recorded for the Chicago-based Solo Art label, which also recorded Jimmy Yancey; these were reissued on Riverside in 1954, and subsequently by London, BYG, and others. He retired in the late 1940s after boogie-woogie went out of fashion. Cripple Clarence Lofton died of a stroke in Chicago on January 9, 1957.

Cripple Clarence Lofton (voc, p); unidentified (perc -1).

prob. Chicago Recording Company, Chicago, December 1943

| 125 | Streamline Train -1 | Pax LP6005, Jazztone J-1224, Vogue EPV-1209, Vogue LDE 122, Jazz Selection JSLP50.021, Gannet GEN5136, Jazz Anthology 30JA5212, Storyville SLP238, Jazmine JSMCD2538, Document BDCD6007 | |

| 126 | I Don't Know-II | Pax LP6005, Vogue L.D.E. 122, Vogue EPV-1209, Jazz Selection JSLP 50.021, Gannet GEN5136, Jazz Anthology 30JA5212, Storyville SLP238, Document BDCD6007 | |

| WC-127 | Policy Blues (Lofton) [CCL voc] | Session 10-014, Pax LP6005, Jazztone J-1224, Vogue LDE122, Jazz Selection JSLP 50.021, Gannet GEN5136, Jazz Anthology 30JA5212, Saydisc Matchbox SDR 146, Storyville SLP238, Document BDCD6007 | |

| WC-128 | I Don't Know (Lofton) [CCL voc] | Session 10-014, Pax LP6005, Vogue LDE122, Jazztone J-1224, Jazz Selection JSLP 50.021, Gannet GEN5136, Jazz Anthology 30JA5212, Saydisc Matchbox SDR 146, Storyville SLP238, Document BDCD6007 | |

| F-129; WC-129 | The Fives | Session 10-002, Pax LP6005, Jazztone J-1224, Vogue EPV-1209, Vogue LDE 122, Jazz Selection JSLP 50.021, Gannet GEN5136, Jazz Anthology 30JA5212, POP SPO 17.003 [EP], Storyville SLP238, Document BDCD6007 | |

| F-130; WC-130 | South End Boogie (Lofton) | Session 10-002, Pax LP6005, Jazztone J-1224, Vogue EPV-1209, Vogue LDE 122, Jazz Selection JSLP 50.021, Gannet GEN5136, Jazz Anthology 30JA5212, Storyville SLP238, Document BDCD6007 | |

| F-140; WC-140 DP | In de Mornin' (Lofton) | Session 10-006, Pax LP6005, Jazztone J-1224, Vogue LDE 122, Jazz Selection LP50.021, Gannet GEN5136, Jazz Anthology 30JA5212, Joker SM 4081, Joker SM 9416, Storyville SLP239, Document BDCD6007 | |

| F-141; WC-141 DP | Early Blues (Lofton) | Session 10-006, Pax LP6005, Jazztone J-1224, Vogue LDE 122, Jazz Selection JSLP 50.021, Gannet GEN5136, Jazz Anthology 30JA5212, Storyville SLP239, Document BDCD6007 | |

| F-142 | I Don't Know (Lofton) | Session 12-005, Gannet GEN5137, Storyville SLP239, Document BDCD6007 | |

| F-143 | Streamlined Train (Lofton) | Session 12-005, Gannet GEN5137, Storyville SLP239, Document BDCD6007 |

The original releases were the 12-inch 78—Session 12-005—and three 10-inch 78s: Session 10-002, 10-006, and 10-014.

Session 12-005 was released in the summer of 1944. Pressed on shellac, the copies that we know of carry red labels; the incised matrix numbers show the F prefix.

Session 12-005 was reviewed by John Lucas in Down Beat on August 1, 1944 (p. 8). "Both of Lofton's numbers have already appeared some years ago [1939] on Dan Qualey's Solo Art, but here the Featheringills give the eccentric boogie veteran plenty of elbow-room and plenty of leeway. Streamline is good, but I Don't Know is great. It's bizarre and hypnotic, in fact, at times smacking more than faintly of the oriental and specifically of the Balinese. In a word it's weird, friends! If you like these, which I hope and expect you will, you really ought to catch Lofton in person. The man is mad!"

On January 1, 1945, the reviewer who went as "Mix" listed Session 12-005 as one of the 10 best "piano discs" of 1944 ("Best Hot Discs of 1944, Down Beat, p. 11). No fewer than 3 Session releases made the list, along with 4 by James P. Johnson on Blue Note and two by Oro "Tut" Soper on rival Chicago-based indie Steiner-Davis.

We have not encountered a postwar re-pressing of Session 12-005. Such a thing would have a WC prefix on the matrix number or some other indicator of involvement from The Bishop Presses.

Session 10-002 was issued in 1944 with a red label and matrix numbers with an F prefix stamped in the wax (in italics). The 1946 re-pressings also have a red label, but now the matrix number has a WC prefix and is stamped in the wax, and the pressings are by Bishop with the center die it often employed ("A Bishop Pressing" is embossed on the label on one side).

A review of the re-pressing appeared in the Record Changer for February 1946 (p. 15). Noting that Lofton's piece called The Fives had nothing in common with the Jimmy Yancey number with the same title, the reviewer says

It is a great piano piece whatever the question of names. Lofton really has only two themes. He plays the first theme about six times, varying it the last two. After the fourth we hear the breaks that Romeo Nelson uses on Head Rag Hop. Listen to Lofton's right hand on this break...

South End Boogie is slow. The introduction barely establishes the tempo but the old foot stomping away can be heard on the record. The piece proper starts with Lofton's left hand deep in the bass. The rhythm of this piece is heavy and musically sonorous. His inventions are very musical and in the medium of the greatest piano jazz. ... This whole boogie blues has a majesty in its slew-foot pace that few boogie pieces have.

The exact release date for Session 10-006 is not known, but the label reads "Copyrighted [sic] 1944." There are earlier copies with a white label and the F prefix in the shellac; the matrix numbers are incised. Later copies have a red label and the WC prefix that is characteristic of Bishop pressings; the matrix numbers are incised (as on the copies of 10-003 and 10-005 that we are familiar with) and there is a Dike-Polzin monogram after the number.

Session 10-014 was released in the first quarter of 1946; it was mentioned in the "Current Records" list in the Record Changer for May 1946. It is known only in copies pressed by Bishop with a red label, a 1946 copyright date, and stamped matrix numbers with the WC- prefix.

Pax LP6005, a 10-inch LP titled Cripple Clarence Lofton, was released in May 1954. George Hulme's Pax listing (in the Matrix 58, 22-26) errs in giving "Deep End Boogie" as the original title of 130; on Session 10-002 it was already titled "South End Boogie." The Pax LP gives the title "I Don't Know-I" to the vocal version (matrix 128).

Vogue L.D.E. 122 is a 10-inch LP released in 1955 under the title Jazz Immortals No. 1: Cripple Clarence Lofton. It is a straight reissue of the Pax LP, using the same master numbers for each side. Probably in 1957, Vogue put out the 4-track EP EPV-1209. On this one, matrix 126 appears "I Don't Know," then on the cover its matrix number is wrongly given as 142!

Jazztone J-1224, a 12-inch LP incorporating material from the 10-inch Pax LPs 6005 and 6011, appeared in March 1956 under the title Pioneers of Boogie Woogie: Jimmy Yancey and Cripple Clarence Lofton.

Jazz Selection J.S.L.P. 50.021 is a 10-inch LP produced by Vogue; like L.D.E. 122 it is a straight reissue of Pax LP 6005 down to the matrix numbers on each side. 128 is titled "I Don't Know, vocal by Clarence Lofton."

Gannet GEN5136 was a British LP released in 1974 as Jimmy Yancey/Cripple Clarence Lofton Volume 1. It gives the title of 126, "I Don't Know-II" as "I Don't Know." Gannet GEN5137 was also issued in 1974, as Jimmy Yancey/Cripple Clarence Lofton Volume 2.

Jazmine JSMCD2538, a British CD titled Boogie Woogie Volume 1: Piano Soloists, also includes "I Don't Know"--either matrix 126 with the vocal or 128 without.

Document BDCD 6007, Cripple Clarence Lofton Vol. 2: 1939-1943 is an Austrian CD released in the mid-1990s. On it "I Don't Know-II" is listed as "I Don't Know No. 2."

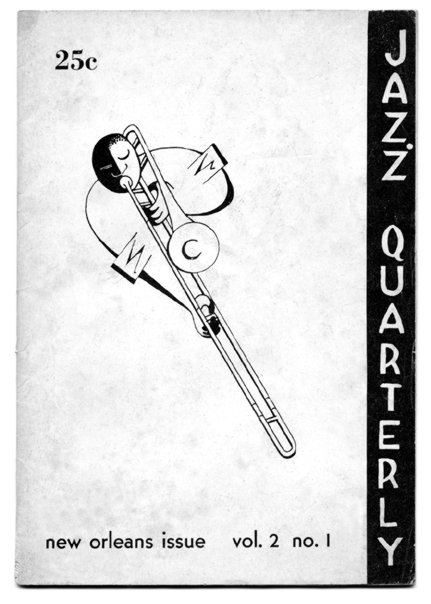

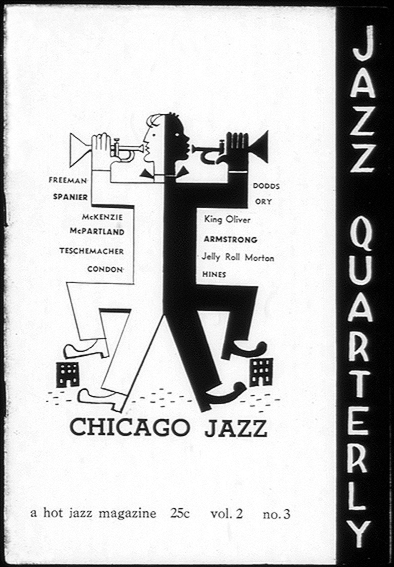

Around the same time that Session was cutting its first new recordings, Phil Featheringill was involved in producing the Spring 1944 issue (Volume 2, Number 1) of Jazz Quarterly, which focused on New Orleans jazz. He contributed several pen and ink drawings to the issue.

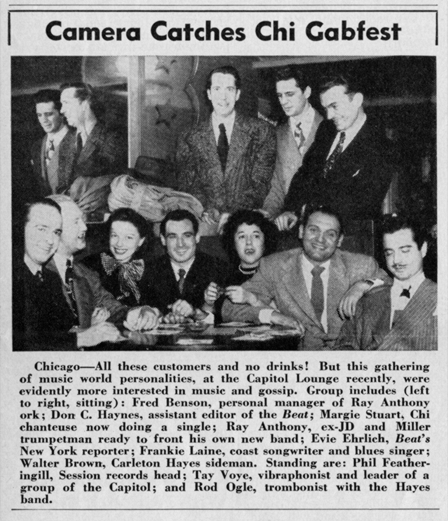

The first combo to appear on Session, led by Trummy Young, was in town playing the Capitol Lounge when Featheringill approached the leader about recording his unit.

James Osborne "Trummy" Young was born in Savannah, Georgia, on January 12, 1912. He began working professionally on the trombone in 1928, in Washington, DC. In 1933 he joined the Earl Hines Orchestra (where he did not solo often on recordings). In 1937 he went with the Jimmie Lunceford band, where he hit full maturity as a soloist. Young also sang comic numbers with the Lunceford band.

After leaving Lunceford in March 1943, Young toured with Charlie Barnet for a little while, then picked up some work with other leaders. Toward the end of the year he started own combo. A profile in Metronome (February 1944, p. 12) states: "In a matter of a few weeks, Trummy has built a six-piece combo that is a 'must' for expert ears. The few less initiated patrons also listen, entranced, to the trombonist-singer's well-planned arrangements." The profile indicates that Young recruited Leo Williams, Harry Curtis, John Malachi, and Tommy Potter (he seems to have added Eddie Byrd when he left Louis Jordan's combo). Accompanying the article were three photos of the group taken at the Capitol Lounge in Chicago. One feature sharply dates the profile: Young had visions of expanding his combo to a big band when the war ended. Wasn't going to happen, but it seems nobody realized it then.

James "Trummy" Young (tb; voc -1); Harry Curtis (as); Leo Williams (ts); John Malachi (p); Tommy Potter (b); Eddie Byrd (d).

Chicago, February 7, 1944

| F-144 | Hollywood (no composer listed) | Session 12-010, Pax LP6008, Classics [Fr] 1037 [CD] | |

| F-145 | Talk of the Town (Cohn) -1 | Session 12-010, Classics [Fr] 1037 [CD] | |

| 146 | The Man I Love (part 1) | Session 12-011 [?], Pax LP6008 | |

| 147 | The Man I Love (part 2) | Session 12-011 [?], Pax LP6008 |

Session 12-010 was released in December 1944 and reviewed in Down Beat on December 15, 1944 (p. 8); it was categorized as "Swing." In Metronome's profile of Trummy Young's combo (February 1944) and its "Exclusive Jazz Discography" (June 1944, p. 25) as well as in the Down Beat review, the saxophonists are identified as Harry Curtis on alto and Leo Williams on tenor (all three sources misspell Malachi's last name, as Session also did in its publicity for the single).

Session promptly ran an advertisement announcing the availability of 12-010 (along with 12-009 by the Session Six and 12-012 and Pete Brown) in the January-February 1945 issue of The Jazz Session.

In his Jazz Discography, Volume 26, Lord puts Leo Parker on alto sax and Harry Curtis on tenor sax, but provides no reason for this alteration. But then he also manages to leave off Session 12-010! Curtis and Williams are mentioned in contemporary accounts of Young's group, and on the labels of Session 12-010. A listen to "Hollywood" reveals an alto sax solo by a somewhat lachrymose Swing player who bears no resemblance to Leo Parker whatsoever.

Known copies of Session 12-010 have a white label and matrix numbers incised in the shellac using the F prefix. Like the contemporary media treatments, the label on 12-010 misspells Malachi as "Malchi."

Session 12-011 was announced during the lifetime of the company and has been listed in discographies; it was meant to contain the two-part treatment of "The Man I Love." We have no evidence that it was actually released, however, and it has consequently eluded the recent reissue program on Classics.

Reviewing 12-010 for Down Beat, John Lucas liked the leader's work but had little praise for the rest of the band: "Hollywood opens with a three-man ensemble sounding like thirty. Harry Curtis plays a solo reminiscent of Tab Smith's alto, then Trummie [sic] comes on for two that are full of slurs and smears, even for a trombone! John Malchi's [sic] piano is fast if nothing else, and Leo Williams' tenor is pretty sad. The closing ensemble is light and buoyant, very amazing for such a set-up! Talk is all Trummie, and the girls will go all out for this side! Young's vocal is certainly cute, for Trummie's either knocked out or groggy. His trombone is just like his singing here, the most typical thing Trummie's ever recorded. Harry Curtis plays an alto as if he's practicing but far from perfect, while Malchi's piano is pleasant if nothing more. Williams' tenor work during the closing ensembles is far better than his work on the reverse."

Otherwise, Session 12-010 got little attention from reviewers. In the Jazzette for March-April 1945 it got onto the "Also Recommended" list (p. 26, no comments about highlights or quality of performance).

Trummy Young's sides for Session were his very first as a leader, and carry the distinction of being done with a working group. Heard today, the Session 12-010 sides have the most "modern" sound of any of the combo recordings Young made during this period, and we are fortunate that this group got to record. While the saxophonists in the group remained obscure, John Malachi would join Billy Eckstine's bop-oriented big band, then settle in Chicago, and Tommy Potter went on to play in several high-profile bop quintets, most notably Charlie Parker's.

Young would continue to record as a leader through 1946, on such labels as Signature (unfortunately not released), Duke (not the famous Houston-based indie of the 1950s), G. I. (unlike the others, a big band session), and HRS. Although the later sessions featured great work by top-flight musicians such as Don Byas on tenor sax and Buck Clayton on trumpet, they were all done with pick-up groups. In 1946 and 1947 Young also participated in the Jazz at the Philharmonic tours, on top of which he led two V-Disc sessions.

In 1947 Young settled in Hawaii, which took him out of circulation as far as most jazz fans were concerned. However, he was back in front of the public from 1952 through 1963 as a member of Louis Armstrong's All Stars, where he developed a highly personal approach to traditional jazz trombone. On leaving Armstrong he returned to Hawaii, though he made occasional tours with different leaders. His later recordings as a leader were few: a session in France for Ducretet Thomson (in 1955), and two LPs done in Hawaii for a company called Flair (1975 and 1979). Trummy Young died in San Jose, California on September 10, 1984.

Pax LP6008 was announced in May 1954 as a 10-inch LP titled Higgy & Trummy; supposedly scheduled for release in June, it was to consist of 3 Trummy Young tracks on Side B and 3 J. C. Higginbotham tracks on Side A. It never came out.

Classics 1037 is a French CD, released in 1998, titled Trummy Young 1944-1946. It includes all of his available 1940s sides as a leader, and is the first actual reissue of Session 12-010. The compilers complained that Session 12-011 (and, of course, Pax LP6008) could not be found.

The company's next session took place in New York City. We are not sure how this was put together--did Featheringill supervise the recording in person? In any event, it featured two musicians with ties to Chicago and its traditional jazz scene.

Milton Mesirow, known for most of his adult life as Mezz Mezzrow, was born in Chicago on November 9, 1899. He began recording in Chicago in 1928, departing for New York later that same year. Opinions of Mezz's clarinet playing continue to be divided: admirers maintain that he was a folk artist, detractors that he was merely out of his league technically. He definitely could play the blues and for many years he was able to hang out—and record—with the greats. (He frequently supported himself by selling "mezzrolls"—a now extinct synonym for marijuana cigarettes—to his fellow musicians, and gained further notoriety with his autobiography Really the Blues, which was published in 1946.) He began recording as a leader in 1933 and was fairly active in the studios until the late 1950s. From 1945 through 1947 operated his own record company, King Jazz, in New York; it is best known today for the string of sessions that Mezzrow recorded featuring Sidney Bechet. The very last King Jazz session was actually made in Chicago in December 1947, while Bechet was working Jazz Ltd. (the club's owners did not want him to leave town during his engagement). It should be noted that Mezzrow generally holds up his end musically on the King Jazz sides. In 1951, Mezzrow moved to France, where he continued to record until 1959, also appearing in two movies. After several years of limited playing activity, he died in Paris on August 5, 1972.

Arthur W. Hodes was born in Nikoliev, Ukraine, probably on November 14, 1904 (there has always been some fuzziness about the year). Fleeing from persecution, his family moved to New York City when he was 6 months old and on to Chicago when he was 6 years old. His first gig was playing solo at the Rainbow Gardens in 1920. By the time he made his first recording with Wingy Mannone in 1928, he had become fully committed to jazz. He remained based in Chicago until 1938, when he moved to New York, working with Joe Marsala and Mezz Mezzrow and then starting his own band in 1941. Hodes first recorded under his own name in 1939 for Solo Art, followed by a session in 1940 for Jazz Record (his own company). Thereafter he recorded for Signature, Jazz Record, Black & White, and Decca. Around two weeks after this session he would begin cutting for Blue Note (no fewer than 4 sessions in 1944, followed by 5 in 1945). From 1943 to 1947, he also edited The Jazz Record, a magazine that promoted traditional jazz. In 1950 he moved back to Chicago, where among other engagements he led the band at Jazz Ltd. in 1953, 1956, and 1957. He continued to record prolifically, while writing extensively about jazz and hosting two TV series. He made his last record in 1989 and had to quit playing after suffering a stroke in 1991. Art Hodes died in Harvey, Illinois, on March 4, 1993.

Mezz Mezzrow (cl); Art Hodes (p); Danny Alvin (d).

New York City, March 5, 1944

| F-160; WC-160-F | Really the Blues (Mezzrow)^ | Session 10-008, Pax LP6013, Classics [Fr] 1074 [CD] | |

| F-161; WC-161-F | Milk for Mezz (Mezzrow)^ | Session 10-008, Pax LP6013, Classics [Fr] 1074 [CD] | |

| F-162; WC-162-F | Feather's Lament (Hodes) | Session 10-007, Pax LP6013, Classics [Fr] 1074 [CD] | |

| F-163; WC-163-F | Mezzin' Around (Hodes) | Session 10-007, Pax LP6013, Classics [Fr] 1074 [CD] |

The session was listed in Metronome (June 1944, p. 25) although no recording date was given.

"Feather's Lament" is a title assigned in cutting irony. At the time Hodes, an ardent "moldy fig," had become Barry Ulanov and Leonard Feather's chief punching bag in the pages of Metronome. In January 1944, the magazine reviewed a Hodes release on another label: "these sound like an amateur band entertaining in an air shelter. Us, we'll face the bombs." In February 1944, Barry Ulanov declared that a live appearance by Hodes: "presented a pathetic set... tinkly, faltering, vapid... really a chore." In March either Feather or Ulanov really went beyond the pale in a review of another Hodes release: "Many of Art Hodes' personal friends... have taken us severely to task for our unkind review... But oddly enough, none of them tried to offer any musical defense. Even men who have worked with him follow the line of reasoning which runs: 'Don't be hard on the guy. We know he can't play, but he's sincere and he means well and he's kind to children.' Alas, we can't let this influence us..." That was the month that Hodes sued Metronome "for heavy damages," according to a brief item that appeared in the April 1944 issue.

Given his bellicose role in the Moldy Fig vs. Modernist brouhaha, Feather didn't much care for Session Records either, despite Phil Featheringill's contributions to Metronome. In his roundup of independent jazz labels, "Waxing Furious," published in the June 1944 issue of Metronome (p. 18), Feather had this to say: "Session Records are in the hands of Phil Featheringill. Reissues and a very few special recordings, pressed in very limited quantities at high prices (three Jimmy Yanceys, as a set, set you back $8.50)." By contrast, trad-friendly reviewers went out of their way to assure potential buyers that 12-inch pressings on Vinylite were worth the extra expense.

Session 10-007 was issued in September 1944, followed by 10-008 around November. 10-007 was released under Hodes' name, while 10-008 came out under Mezz Mezzrow's name.

Early pressings of Session 10-007 have white labels and the F prefix on incised matrix numbers; later pressings also have white labels but show the WC prefix on stamped matrix numbers, and an F suffix. One side on the later pressing shows the embossed Bishop logo. On the "Mezzin' Around" side, an error is corrected by striking through a digit, so the matrix number reads WC-1603-F.

Earlier pressings of Session 10-008 carry white labels and the F prefix on the incised matrix numbers; later pressings have red labels, the Bishop pressing log embossed on one side, and a WC prefix to stamped numbers (there is also an F suffix—was this just carried over from the first pressing, or did it have some other meaning?). Both editions show a 1944 copyright date on the labels.

This session is covered in Lord's Jazz Discography, Volumes 9 and 14. Lord hypercorrects "Mezzin' Around" to "Messin'" in his listing under Art Hodes' name. But then Lord lists 162 and 163 a second time under Mezzrow's name, this time "Mezzin'" it up properly. (In his Mezzrow entry, Lord throws in a track titled "My Daddy Rocks Me," which was not recorded for Session.)

Session 10-007, which listed Hodes as the leader, got a review from John Lucas in Down Beat on October 1, 1944 (p. 8). "On the Session sides Art manages to tear Mezzrow away from his book long enough to cut the best clarinet he has ever waxed. The first is all Mezz's, a clarinet jump that builds up and up dynamically so that the tension increases all the way. Hodes' piano and Alvin's drums furnish excellent accompaniment, but this number is really strictly for Mezz. The reverse is a slow blues, played with deep feeling by all three, especially by Art."

Metronome predictably jumped all over 10-007 in its October 1944 issue (pp. 25-26). The reviewer gave "Feather's Lament" a C- and "Mezzin' Around" a D. "The Hodes Trio, Art, Mezz Mezzrow, and Danny Alvin, is consecrated to the purpose of presenting Mezz's feeble clarinet. On the Lament you have a lot of uncertain groping on the clarinet and a really lamentable cut-off in the middle of the last chorus, as if the engineer said stop and they just stopped. Some phrases reminiscent of Mezzrow's Apologies begin a curious exhibition of clarinet on Mezzin' Around, some frantic one-note bleating, some stiff fingering, unrelieved by any sounds we could find pleasant."

Session 10-008 got the typical exultant Lucas treatment in Down Beat on December 15, 1944 (p. 8). Categorized as a "hot jazz" offering, it was praised by the reviewer who noted the ardent blues playing on both sides: "Here are shades of Jimmie Noone and, say, Paul Barbarin or Zutty Singleton. These three white jazzmen have kept faith!"

In the January 1, 1945 issue of Down Beat, the "Best Hot Discs of 1944" featured competing lists by "Jax" (whose real name was John Lucas) and "Mix." On the "Mix" list, Session 10-007 made the top 10 for "Piano Discs" (p. 11).

Pax LP6013 was titled Dixie a la Hodes and was advertised in the Record Changer, December 1954. (It had not been included in Pax's catalog of May 1954.) The four titles from this session were to appear on Side A of this 10-inch LP. It is not known what was intended for Side B, but obviously it had not been made for Session. The LP was never released.

We know of just one (!) further reissue of this material: all 4 sides from this session appeared on Classics 1074, a CD released in 1999 under the title Mezz Mezzrow 1944-45.

Session matrix numbers 148 through 153 were attached to the reissue 78s that came out in March 1944 on Reissue Session 5 through 7; see the Reissue section at the end of the page for more about these. Unfortunately Featheringill lost track of his matrix assignments two years later; he ended up reusing 154 and 155 for his final reissue effort on Reissue 8. (Because the two sessions recorded in New York City were entered into the master book later, their matrix numbers don't line up with the recording dates.)

Session continued its trad jazz efforts with 4 12-inch sides by a band led by the legendary Richard M. Jones.

A veteran of the Chicago scene, Richard M. Jones was born in Barton, Louisiana on June 13, 1892. (His middle name has been given variously as Mariney and Myknee; in his later years he was addressed as "Myknee," pronounced like "my knee.") He worked in New Orleans as a pianist from 1908 to 1918. He arrived in Chicago in 1919, finding employment in Clarence Williams' music publishing house. He first recorded in 1923, when he did laid down two piano solos for Gennett. In 1925 and 1926 he recorded as a leader for OKeh, where he also functioned as the recording director for many blues sessions. He would become most famous, however, for supervising the sessions by Louis Armstrong's Hot Five. He also recorded a session with King Oliver's Dixie Syncopators (1926) and appeared on Willie Hightower's only session (1927). He subsequently cut three sessions for Victor (1927 and 1929), Gennett (under the pseudonym "Wally Coulter," 1927), and Paramount (1928). In 1935, Jones made three sessions in Chicago for Decca and in 1936 he cut two sides for Bluebird; in 1940 he recorded with Jimmie Noone for Decca. Preston Jackson (1902-1983; on the Chicago scene since 1917) had appeared on three of Jones' OKeh sessions in 1926. For a time he ran a record store; he also was involved in distributing OKeh records. Jones gained some renown as a songwriter; his most famous tunes were "Trouble in Mind" and "Caldonia."

A veteran of the Chicago scene, Richard M. Jones was born in Barton, Louisiana on June 13, 1892. (His middle name has been given variously as Mariney and Myknee; in his later years he was addressed as "Myknee," pronounced like "my knee.") He worked in New Orleans as a pianist from 1908 to 1918. He arrived in Chicago in 1919, finding employment in Clarence Williams' music publishing house. He first recorded in 1923, when he did laid down two piano solos for Gennett. In 1925 and 1926 he recorded as a leader for OKeh, where he also functioned as the recording director for many blues sessions. He would become most famous, however, for supervising the sessions by Louis Armstrong's Hot Five. He also recorded a session with King Oliver's Dixie Syncopators (1926) and appeared on Willie Hightower's only session (1927). He subsequently cut three sessions for Victor (1927 and 1929), Gennett (under the pseudonym "Wally Coulter," 1927), and Paramount (1928). In 1935, Jones made three sessions in Chicago for Decca and in 1936 he cut two sides for Bluebird; in 1940 he recorded with Jimmie Noone for Decca. Preston Jackson (1902-1983; on the Chicago scene since 1917) had appeared on three of Jones' OKeh sessions in 1926. For a time he ran a record store; he also was involved in distributing OKeh records. Jones gained some renown as a songwriter; his most famous tunes were "Trouble in Mind" and "Caldonia."

Richard M. Jones (p); Bob Shoffner (tp); Preston Jackson (tb); Darnell Howard (cl); John Lindsay (b); Warren "Baby" Dodds (d).

Chicago, March 23, 1944

| F-154-C | 29th and Dearborn (Jones) | Session 12-006, Pax LP6010, Folkways FJ2817, Carrousel CAR19, Gannet CJR1002 [CD], Classics [Fr] 853 [CD] | |

| 154 [alt.] | 29th and Dearborn (Jones) | Gannet CJR1002 [CD] | |

| F-155-B | New Orleans Hop Scop Blues (Thomas) | Session 12-006, Pax LP6010, Folkways FJ2817, Carrousel CAR19, Gannet CJR1002 [CD], Classics [Fr] 853 [CD] | |

| 155 [alt.] | New Orleans Hop Scop Blues (Thomas) | Gannet CJR1002 [CD] | |

| F-156-A | Jazzin' Babies Blues (Jones) | Session 12-007, Pax LP6010, Folkways FJ2817, Carrousel CAR19, Gannet CJR1002 [CD], Classics [Fr] 853 [CD] | |

| F-157-A | Canal Street Blues (Oliver-Armstrong) | Session 12-007, Pax LP6010, Folkways FJ2817, Carrousel CAR19, Gannet CJR1002 [CD], Classics [Fr] 853 [CD] |

The original releases on Session 12-006 and 12-007 were given a detailed advance review by George Hoefer, Jr. in his column "The Hot Box" (Down Beat, April 15, 1944, p. 13); about the release plans Hoefer merely said "these records should be out soon." Hoefer supplied the complete personnel, along with titles, couplings, and rundowns of the soloists on each side.

The copies of Session 12-006 and 12-007 that we have seen were are pressed on shellac; they have red labels and the F prefix in front of the matrix numbers, which are incised in the shellac. The copy of 12-006 in Konrad Nowakowski's collection actually has the red labels pasted on top of blank labels, rather like the early Vinylite editions of 12-001 through 12-003. We don't know whether other copies of 12-006 all look like this.

George Hoefer Jr.'s advance review in Down Beat(see above) was strongly enthusiastic. Of 12-006 Hoefer said:

The Jones opus dedicated to a south Side corner [29th & Dearborn] is played in a medium tempo with fine rhythm background. Long solos by Howard, Jackson and Shoffner. The composer of the tune that was renovated by Bob Crosby under the name Dixieland Shuffle plays a piano chorus. The N. O. Hop Scop which was written years ago by George W. Thomas is introduced by Jackson's trombone and an an ensemble chorus followed by Jackson in solo, Howard's clarinet playing reminiscently similar to his cousin Barney Bigard, a drum-piano duet with Baby riding the rimes, and Shoffner's trumpet sounding off in the Oliver Vocalion tradition. The finale of the rendition is of all things a session of close riffing by these jazz individualists.

Hoefer's thoughts about Session 12-007:

[Jazzin' Babies Blues] is of course another famous Richard Jones tune which also saw service as Tin Roof Blues. Opened by Jones himself playing some of that mean sporting piano of Storyville followed by Howard in the high register, the rendition continues unabated in the best Dixieland manner. This is probably the best of the four sides. Felt throughout these records and especially in Jazzin' is the solid bass support rendered by John Lindsay, a fine musician. The last side is the Oliver-Armstrong tune [Canal Street Blues] made famous by the Creole Band Gennett record. Done in a faster tempo it showcases noteworthy solos by all the participants.

When the records were commercially released, Down Beat followed up with an official review of 12-006 and 12-007 in its issue of August 1, 1944 (p. 8). According to John Lucas, "When I heard the test pressings of these platters, less than half a day after they were waxed, I declared vehemently that they were the best examples of real New Orleans jazz ever cut. Perhaps I'm prejudiced, but I still think so. They have minor flaws of course, but such insignificant moments only serve to enhance the magnificent effects of the whole performance." Lucas reserved his highest praise for Darnell Howard's clarinet work (as good, he says, as anything by Johnny Dodds, Jimmie Noone, Omer Simeon, or Sidney Bechet...), with Preston Jackson's trombone solos just behind. He also singles out the way the drums were recorded: "Thank God, someone's finally got Baby's drums down on wax just as they sound in person!"

Also firmly in the trad camp, The Jazz Session put 12-006 in at number 4 on its list of the "Ten Best Recordings of 1944" (January-February 1945, p. 22). The other entries were by Wild Bill Davison's Commodores, Art Hodes' Blue Note Seven, Muggsy Spanier's Ragtimers, Miff Mole's Nicksieland Band, George Bruns' Jazz Band, Kid Ory's Creole Jazz Band, and LaVere's Chicago Loopers.

The opening comment in Hoefer's column of April 15 seems apropos here: "Hostilities between the advocates of basic jazz and the modernists of swing are beginning to become more evident." (In the first half of 1944, the battle lines were not yet drawn around bebop; too few critics were aware of it yet.) Metronome, whose reviewers were solidly in the modernist camp, was obligingly scathing in its response to this material. 12-006 and 007 were reviewed together in the October 1944 issue (p. 26), on which all four sides were handed the grade of C-. "Nothing, absolutely nothing, though there are some well known musicians on this date... The boys go through their New Orleans paces about a mile back of the microphone, playing corny riffs, ragging the scale mercilessly. And we must confess that Baby Dodds' drumming, an unending stream of rim-shots, is absolute anathema to us."

The Summer 1945 issue of the Needle (Volume II, number 1) ran a detailed review of both 12-inch releases. The praise is faint: "One finds that these records are not as bad as they appear with casual listening. The bad balance in recording, bad pressing, and the lack of 'hang together" throughout the entire session, greatly overbalance the evident ability of the men to play better than average music, at least individually, if not collectively." Preston Jackson and Baby Dodds both get kudos for their individual contributions, but... "One who expects to hear good New Orleans music on these records will be frustrated by the total lack of collective improvisation and, as Dixieland, Jump or Swing, they fall down completely" (p. 56). Since the reviewer wasn't evaluating the Jones sides as bebop, that meant they weren't effective examples of any jazz genre, from his point of view.

Hoefer's column for October 1, 1945 credits Jones with being "a walking encyclopedia of jazz history, and what is more a stickler for the correct credit to the correct person" (p. 11). Most of the column reported personnels that Jones had provided for several of his recording sessions of the 1920s and 1930s. Jones got a big break around this same time, when he was hired to do A&R for the brand-new Mercury label, which started up in October 1945. He recorded such artists as June Richmond, the Four Jumps of Jive, Karl Jones, and the Cats 'n' Jammer Three for the new company, but his tenure was cut short when he died on December 8, 1945. One of the sides he supervised was a new version of "Trouble in Mind," sung by Sippie Wallace and backed by a group led by Karl Jones.

Down Beat ran a long tribute to Jones ("Reminiscences on the Career of a Jazzman" by Paul Eduard Miller) in its March 25, 1946 issue (pp. 10-11). "Richard M. Jones was a big man. He stood six feet four, carried his 250 pounds with grace and ease. His heart was even bigger: no jazzman did more (if as much) to help his fellow-musicians and to promote the jazz music in which he believed so completely." Some of the material in this article lacks credibility: there was no need for Jones to introduce Jelly Roll Morton around musical New Orleans, since The Roll was a native of the Crescent City, and (at least) two years older than Jones besides. But the story that Jones recommended King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band to Gennett in 1923 makes more sense, as does the story that he helped get Ma Rainey to Chicago to make her first recordings there. Miller reminded readers of Jones' authorship on "Jazzin' Babies Blues," "Riverside Blues," "Mushmouth Blues," and "Southern Stomps," among other pieces—as well as the appropriation of composer credit for these numbers by other musicians.

Pax LP6010 is a 10-inch LP, listed as for sale in May but actually released in October 1954 (and reviewed in the November issue of the Record Changer) under the title New Orleans Stylings: Richard M. Jones Jazz Wizards and Punch Miller Stompers. Jones gets all three tracks on Side A and one on Side B. (Lord fails to list any of these appearances on Pax LP6010.)

Gannet CJR1002 is a British CD titled New Orleans to Chicago: The Forties. The rest of the CD is by Punch Miller (see below), Karl Jones (who recorded for Mercury in 1945), Little Brother Montgomery, and Preston Jackson.

Classics 853 is a CD released in the mid 1990s under the title Richard M. Jones 1927-44.

After the Richard M. Jones date, matrix numbers 158 and 159 are unaccounted for.

An unsettled question about the next session, co-led by Ben Webster and Sid Catlett, is whether it was really done on a different date from the Hodes/Mezzrow outing. Did Phil Featheringill travel to New York City twice in the same month (during World War II, when travel could be difficult)? Did he delegate the supervisory role in one or both sessions? Or did he get both of them done on one visit? Here we are going with previously publicized session dates, but details remain that we would like to learn more about.

About Ben Webster (1909-1973), one of the greatest tenor saxophonists of the period, we will have more to say in a little while.

One of the top drummers of the Swing era, Sidney Catlett ("Big Sid") was born on 17 January 1910, in Evansville, Indiana, and attended high school in Chicago. After working in local bands a few years, he moved to New York in 1930. He subsequently played with Benny Carter (1933), McKinney's Cotton Pickers (1933-34), the Jeter-Pillars band of St. Louis, Fletcher Henderson's Grand Terrace band (1936), Don Redman (1936-38), and Louis Armstrong's big band (1938-42). Catlett also briefly played with Benny Goodman (1941). From 1944 to 1946, he was leading his own combos in California and New York City and doing extensive session work for several labels. (He is in particularly good form, and particularly well recorded, on the sessions that he made for Keynote in 1943 and 1944, under such leaders as Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins.)

Ben Webster (ts except *); Sid Catlett (d); Marlowe Morris (p); John Simmons (b).

New York City, March 25, 1944

| WC-170-F | Perdido (Tizol)^ | Session 10-010, Onyx ORI 217, New World NW 284, Xanadu FDC5170 [CD], EPM Musique FDC5170 [CD], Classics [Fr] 1017 [CD] | |

| WC-171-F | I Surrender Dear (Barris-Clifford)^ | Session 10-010, Onyx ORI 217, New World NW 284, Xanadu FDC5170 [CD], EPM Musique FDC5170 [CD], Classics [Fr] 1017 [CD] | |

| F-172; WC-172-F | 1-2-3 Blues (uncredited) | Session 10-009, Onyx ORI 217, Classics [Fr] 1017 [CD] | |

| F-173-A; WC-173-AF | I Found a New Baby (Williams-Palmer)* | Session 10-009, Onyx ORI 217, Classics [Fr] 1017 [CD] |

Our proximate discographical information comes from Lord's Jazz Discography Volumes 4 and 24. The session was listed in Metronome (June 1944, p. 25) albeit without a recording date. Session 10-010 from this session was a 10-inch 78 issued under Ben Webster's name; Session 10-009 was released under Sid Catlett's.

Session 10-009 is known in copies with an incised F prefix in the trail-off area (the first pressing), and in copies pressed by Bishop with a red label and a stamped WC prefix in the trail-off area. At least one copy (from the later pressing, by Bishop) ended up with on red label and one white one.

Session 10-010 is known in copies pressed by Bishop with a WC prefix to the stamped matrix number; there may also be pressings with an F prefix, but if so these still need to be verified by collectors.