Revision note. We have updated our information on Joseph De Johnette's Haven label (which may have planned to record Prince Cooper, but so far as we know never actually did). We have added photos of a gospel acetate (by the "Spitual" Voices) formerly in Bill Sabis's collection.

Club 51, which existed from 1955 to 1957, was one of the myriad mom and pop labels that briefly made their appearance in Chicago during in the post-World War II efflorescence of independent label recording activity. The label grew out of the various enthusiasms of local entrepreneur Jimmie Davis and his wife Lillian.

Club 51 operated as part of the Davises' Savoy Record Mart at 527 East 63rd Street. It was not their main business enterprise. Two blocks west was their principal interest, the Park City Bowl skating rink at 345 East 63rd (on the corner of 63rd and South Parkway Boulevard). Davis was the foremost advocate of roller skating in the black community. In December 1938 he had inaugurated roller skating nights at the famed Savoy Ballroom, 47th and South Parkway. Davis served as assistant manager of the Savoy Ballroom until 1947, when he left the faltering operation to become manager of the Park City Bowl. (After a final bid to build attendance by bringing in high profile artists like Duke Ellington and Charlie Parker, the Savoy folded quietly in July 1948.)

The Park City Bowl was born out of racial change on the city's South Side. For decades the skating rink was known as the White City Bowl; it was the only facility to remain from the famed White City Amusement Park complex after most of it burned down in the late 1920s. During the early 1940s, there was much racial conflict over White City's ban on African American clientele. Its location in the black community and its name unintentionally but obviously redolent of segregationist policy made the conflict particularly intense. The Defender described White City as an "anti-Negro stronghold." Finally, in 1947, White City was turned over to new management and was renamed the Park City Bowl with an open door policy for all races although it attracted primarily African Americans.

As manager (and later owner) of the Park City Bowl, Davis and his wife Lillian could keep their fingers on the pulse of the black entertainment scene, because the facility did not just serve as a skating emporium--it was also a venue for concerts sponsored by local black deejays, mainly McKie Fitzhugh. The couple thus became well acquainted with both the amateur and the professional talent in the city.

Jimmie and Lillian soon built a small rehearsal studio in the back of their record store, and eventually launched a label. Davis wanted to call his label Savoy, but because the name had been taken by the already famous New Jersey-based company, he settled on Club 51. The company was in the planning stages for a while. The decision to sign the vocal group the Four Buddies (as Davis insisted on calling them) was made in the Fall of 1954, and Davis's holdings included some demos (either made in his rehearsal studio or made elsewhere and submitted to him) that have 1954 dates on them. Davis and his wife finally started the label in late March of 1955, as reported in the April 8, 1955 Kansas City Call, which said that the firm was "opened for business" the previous week. The paper reported that Paul Gill would be in charge of sales and that Dave Clark would be in charge of promotion. These two individuals were undoubtedly freelancers who took on Club 51 as a client. (For instance, in 1953 and 1954 Dave Clark had done some work for the larger United label.)

The acts recorded for the label were an assortment of combos, standup R&B and blues singers, and vocal groups: Prince Cooper, Rudy Greene, Bobbie James, Honey Brown, Sunnyland Slim, Five Buddies, and the Kings Men. The biggest name was Sunnyland Slim. The Kansas City Call reported that three releases by Prince Cooper, Rudy Green, and Bobbie James would constitute the initial release.

Accompaniment to vocalists was initially provided by tenor saxophonist Eddie Chamblee and his combo. When Chamblee left town in 1955 to go on tour with Lionel Hampton’s big band, his place was taken by guitarist William "Lefty" Bates, an experienced studio musician with many sessions at Vee-Jay, United/States, Chance, and Parrot under his belt. While Davis supervised the recording sessions (today he would be called a producer), Chamblee and later Bates directed the band. Said Jimmy Hawkins of the Five Buddies about the operation, "Davis would record a lot of our stuff in his practice studio first. Then we would go to Universal and have a regular session, but he was always having a hard time getting money for the sessions. I don't know how he recorded as many people as he did. He did have a successful record shop, so maybe the money came from that as well as the skating rink."

The practice studio was used by many groups in the community to make audition dubs to take to other companies. Davis charged two dollars an hour for studio time and $2.50 a dub, and other Chicago companies, particularly Vee-Jay, had aspiring groups cut their audition dubs at Davis's studio to save time. Davis reportedly made hundreds of such dubs.

Before the label opened for business, a number of singers and combos were bidding for a chance to record on Club 51. According to Richard Reicheg, Davis had in his possession demos made by singer Jean Carroll and several by the Freeman Brothers Band (featuring Von Freeman on tenor sax, George Freeman on guitar, and Bruz Freeman on drums), including one on which they backed singer Bobbie James. Bobbie James ended up recording for Club 51; the Freeman Brothers didn't.

In his interview with Richard Reicheg many years ago, Jimmie Davis insisted that his label began in 1951, and he offered the name as confirmation. But Leadbitter and Slaven, in their 1987 volume, give 1955 dates for Prince Cooper, Rudy Greene, and Honey Brown (this last actually turns out to be from 1956), and the Kansas City Call article nails down early 1955 for sessions Cl1 and Cl3/Cl4.

In all, we know of seven releases by the company, numbered 101, and 103 through 108. There was never an official Club 51102, which presumably would have shown matrix numbers 22103 and 22104. However, Jimmie Davis circulated a few copies of lacquers by other artists, which were variously marked as 102, C106, and C107, then ended up not releasing them. As was standard practice at the time, all full-dress Club 51 releases appeared on both 78 and 45 rpm. Those seven represent a typical boutique operation, which typically for the city's black music scene melded jazz, doowop, blues, and pop. Including the items that Jimmie Davis considered for release but did not carry out his plans for yields three additional 78s, and adds gospel to the genres covered.

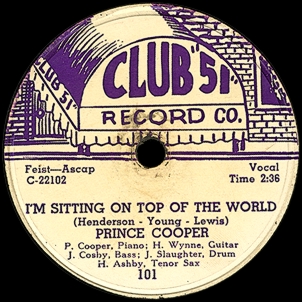

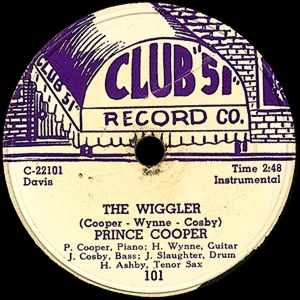

Robert "Prince" Cooper (voc -1, p); Harold Ashby (ts -1); Wilbur Wynne (eg); Jimmy Cosby (b); James Slaughter (d, Latin perc).

Chicago, Universal Recording, March 1955

| C-22101 | The Wiggler (Cooper-Wynne-Cosby) | Club 51 101 | |

| C-22102 | I'm Sitting on Top of the World (Henderson-Young-Lewis) -1 | Club 51 101 |

Prince Cooper was born Robert L. Cooper on October 14, 1921. He attended Tilden Tech high school in Chicago. In his youth he took up concert violin, but his interests eventually drifted toward jazz, and he began playing the piano in 1937. He served in the Army in World War II. On returning to Chicago in 1944, he found work first in the the stockyards and then at International Harvester. He got his first professional job in February 1946, as the pianist for Marvin Cates and His Earls of Rhythm, who were performing at Jack's Club Showboat (6109 South Parkway). Another up-and-comer in that band was tenor sax blower Eddie Chamblee.

With the Cates band Cooper developed a knack for singing. Jack Ellis, the owner of the club and former Defender band columnist, was particularly impressed with Cooper, and had him form a trio to replace the Cates band. Cooper recruited Hurley Ramey on guitar and Jimmy Cosby on bass, and the Robert "Prince" Cooper Trio performed in a long residency at the club from June 1946 to the end of the year (Cooper posted a 5-month contract with Jack's Showboat on May 16 and extended it for 8 months on September 16). The Cooper trio was still holding down the gig in June 1947, posting an extension for another 6 weeks on June 19, 6 more months on July 17, and 6 months on October 2. The engagement seems to have ended a little prematurely in January of 1948, when Prince Cooper moved to the Music Box (408 East 63rd Street; indefinite contract posted on January 22).

The Prince Cooper Trio patterned its sound very closely after the Nat King Cole Trio; Jack's Club Showboat advertised Cooper as "King Cole's Double." The group cut some sides for Exclusive in Los Angeles in 1946 (two were released; the company was in no hurry with them, as Exclusive 94x was reviewed in Cash Box on May 7, 1949, p. 11). On the Exclusive session, Lord lists the bass player as Charles "Truck" Parham, but it was probably Cosby (unless the recording was actually done later). When the trio recorded for the new Aristocrat label in September and December 1947 (most notably "It's a Hit Baby"; eight cuts were done in two sessions, and six were released), Parham was definitely responsible for the bass work. "It's a Hit Baby" shows just how close to King Cole Cooper could get at the time.

The Cooper trio worked steadily in Chicago over the next few years: In June 1948 they were working Kennedy's Honeydripper Lounge at 5910 South State (indefinite contract accepted and filed on June 3). In April 1950 they made a stop at Don's Den (461 East 61st; 10 week contract accepted and filed on April 20) and in November 1950 they were working Fuller's Lounge at 4700 South Wentworth (according to an "indefinite" contract filed with Musicians Union Local 208 on November 16, 1950).

In 1951 Cooper formed a new trio with Wilbur Wynne and Jimmy Cosby and played for two years at the Avenue Lounge (64th and Parkway), owned by Joseph De Johnette. (Cooper's contract with the Avenue Lounge, another "indefinite," was accepted and filed by Musicians Union Local 208 on October 4, 1951). For a time Wynne dropped out to work with Ahmad Jamal's trio; when he was not available, Cooper used Emmett Spicer, formerly with Duke Groner's trio and the Four Shades of Rhythm, on guitar instead. For instance, when the trio played the Luther Rawlings Cocktail Lounge (4711 South Cottage Grove), the Defender for May 9, 1953 gave the lineup as Cooper, Cosby, and Spicer. The contract with Luther's Lounge was for 6 months (according to the Local 208 Board minutes for May 7) but no such ambitions were fulfilled. Within 6 weeks the trio would return to the Avenue Lounge, where their indefinite contract was accepted and filed on July 16, 1953.

In October 1953 Wynne rejoined Cooper. At that time the trio was scheduled to go into the studio for De Johnette who planned a "new recording company" that he said would begin operations in the fall (we're getting this from the Chicago Defender of October 1, 1953). The trio seems to have stayed at the Avenue Lounge through the end of the year. A few months after the announcement in the Defender, DeJohnette joined with Orlando Murden, who played the harp and the piano, to start a label called Haven (Cash Box, February 20, 1954, p. 27). Haven was responsible for a handful of releases, but, if Prince Cooper actually recorded for it, we have yet to find anything by him.

On February 4, 1954, Local 208 posted Cooper's indefinite contract with the "Kit Kat" Club. After two weeks, the trio moved to the 411 Club (indefinite contract accepted and filed on February 18). In August, he took an engagement at the Pershing Lounge (contract filed on August 19). In early October, the trio was back at the 411, posting another indefinite contract on October 7, 1954. In December, his trio returned to the Kitty Kat Club, to judge from some publicity in the Defender.

By the time of his Club 51 session, Cooper was working on the North Side at the Club Laurel (1733 West Lawrence); his indefinite contract was accepted and filed on January 20, 1955. Relations with the owner grew tense, however, because Cooper wanted to increase the size of his group. According to the Local 208 Board meeting minutes of March 3, 1955:

Cooper stated that Mr. McLaughlin, the owner of Club Laurel came to him and stated that he would have to cut the band to three pieces or be dismissed. Cooper also explained that Mr. McLaughlin only wanted four musicians in the beginning and that he insisted that he use five musicians. (p. 1)

As of March 3, Cooper was working three nights a week at the club with a trio and two nights with a quintet. The reason the Board was concerned about any of this was that Wilbur Campbell had brought a claim against Cooper, allegedly for dropping him down to two days a week without notice. The Board denied Campbell's claim, but he presumably found another gig as soon as he could, and James Slaugther took the drum chair for the Club 51 session. Apparently Cooper remained in good standing with the owner, for he did not move his trio to another club until June (contracts filed with the Kitty Kat Club and the New Esquire Lounge, both on June 16). Cooper's trio was replaced at the Kitty Kat in early August, when Ahmad Jamal took over; we are not sure when the New Esquire gig ended.

For the session Cooper's trio was joined by two of the top jazz musicians in town, Harold Ashby (1925-2003) on tenor sax and James Slaughter on drums. Presumably they were also in his working band two nights a week at Club Laurel. Judging from "The Wiggler," on which he and Wilbur Wynne are the dominant voices, Cooper had moved beyond the King Cole influence in his piano playing. But apart from Ashby's tenor sax solo, "Sitting" is still in the Cole mold.

After his Kitty Kat gig ended, Prince Cooper dropped off the 208 contract lists for several months (he may have been on the road, or working in the suburbs). He resurfaced at the Stage Lounge in mid-1956.

According to Richard Reicheg, a Club 51 acetate is extant of two more sides by a Prince Cooper group. This was given a stick-on purple on white label and a tentative release number (C107) was typed in, but Davis changed his mind and used 107 for Honey Brown's record instead. See Cl8 below.

Cooper in later years moved to Elgin, Illinois, about 30 miles west of Chicago, and played regularly in the lounges in Elgin and other towns along the Fox River. He died in Elgin on January 4, 1998.

Leadbitter and Slaven (1987) give 1955 as the recording date; the Kansas City Call article allows us to be more precise. The session personnel were listed on the label; we've added full first names. We derived some biographical details from Joe Segal's notes on the Chess South Side Jazz LP, which includes two of Cooper's Aristocrat sides; however, Segal gives an incorrect birth date for Cooper (October 13, 1927).

Since our information about Club 51 is primarily based on the issued sides and secondarily on acetates that have come to our attention (if there was ever such a creature as a company master book, it's long gone), we're not in a good position to know about additional tracks cut at the sessions. Cl3 and Cl4 form the only industry-standard 4-tune session that we can document. According to Dickie Umbra and Ularsee Manor, just two tunes were done in session Cl5; they say they wished they could have done two more. All the same, our guess is that the missing Club 51 102 contained (or at one time was intended to contain) the rest of this Prince Cooper session. In the company's report to the Kansas City Call no other artists were mentioned among the initial releases.

Still, Jimmie Davis at one time had plans for a 102 by a different group.

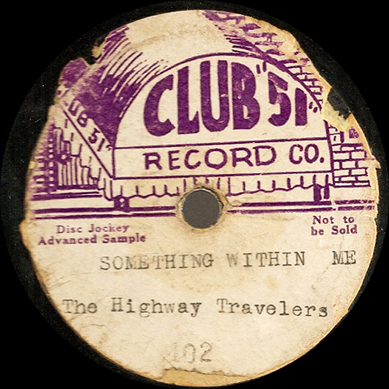

Unidentified male vocal quartet.

Chicago, early 1955

| Something within Me | Club 51 102 (unissued lacquer) | ||

| After I Die | Club 51 102 (unissued lacquer) |

There have been a number of reports over the years about a Club 51 102 by a gospel group, The Highway Travelers. Jimmie Davis got far enough along with the project to make a few acetates with 102 on them and distribute them to disc jockeys. There is no evidence that Club 51 ever released the single. The only surviving copy was in the collection of Bill Sabis. One side is shown here because, on the other, only about 10% of the flimsy stick-on label remains, with the fragmentary inscriptions "r I Die" and "Highway Travel."

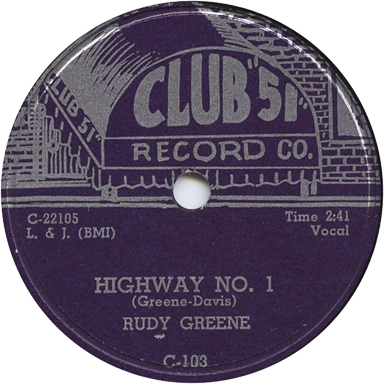

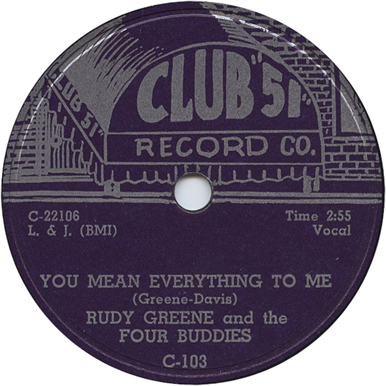

Rudy Greene (voc; eg) with The "Four" Buddies: Ularsee Manor, Jimmy Hawkins, Irving Hunter, William Bryant, Dickie Umbra (voc on ^ only); accompanied by Eddie Chamblee Combo: Eddie Chamblee (ts); Robert "Prince" Cooper (p); unidentified (b, d).

Universal Recording, Chicago, March 1955

| C-22105 | Highway No. 1 (Greene-Davis) -1 | Club 51 103 | |

| C-22106 | You Mean Everything to Me^ (Greene-Davis) | Club 51 103, Relic 5059 |

In March 1955, Jimmie Davis brought into Universal Studios the blues man Rudy Greene, R&B singer Bobbie James, and the Five Buddies. These Greene tracks were recorded at the same session as the Bobbie James number, according to Dickie Umbra of the Five Buddies. The matrix numbers and the instrumental support confirm the report. Jimmie Davis told Dick Reicheg that he used Eddie Chamblee's group on this session. Ularsee Manor confirms that Chamblee was on tenor sax and adds that Prince Cooper was the pianist: "Cooper was like the house band."

We've learned that some copies of Club 51 103 actually carried a credit to the "Eddie Chamblee Combo." Bill Sabis owns one, on which the credit has been erased on both sides. (See the next session, Cl 4, for "erased" label copy on Club 51 104.)

Edwin Leon Chamblee was born in Atlanta, Georgia, on February 24, 1920. He attended Wendell Phillips High in Chicago, where he was a classmate of Ruth Jones (better known to posterity as Dinah Washington). From 1941 to early 1946 he worked as musician in Army bands. Returning to Chicago, he began an association with the Miracle label. Initially he appeared as a sideman on sessions with Dick Davis and Sonny Thompson, but after the tremendous success of Thompson’s "Long Gone" (a two-sided blues instrumental featuring Chamblee’s solo on Part II), he began recording for Miracle as a leader, scoring a hit with "Back Street" in 1949. He stayed with Miracle until it folded in 1950, then cut two more sessions for its successor label, Premium. In 1952, Chamblee did one session for Coral (a Decca subsidiary), then began an association with the United label that lasted until the end of 1954. While at United, he backed the extremely popular Four Blazes in the studio, accompanied the vocal group The Five Cs, and cut three sessions of what was picturesquely billed as "The Rockin' and Walkin' Rhythm of Eddie Chamblee."

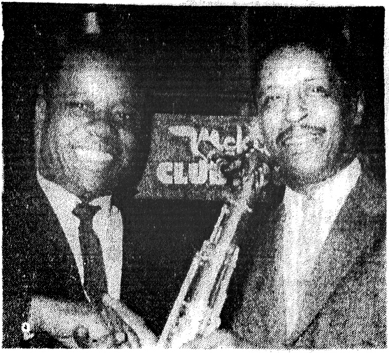

After his work for Club 51, he went on the road with Lionel Hampton's big band in 1955-1956. In 1957 and 1958 he worked with singer Dinah Washington (he was briefly Dinah's fifth husband; the relationship came to a end when she made her point in a quarrel by smashing his saxophone against a barroom wall). He recorded two jazz LPs in Chicago for EmArcy in 1957 and 1958, on Dinah Washington's recommendation (she was a Mercury artist); he also accompanied her on many of her own sessions. After splitting with Dinah Washington, he enjoyed a run of several months at McKie's Disc Jockey Lounge in 1958. Subsequently Chamblee moved to New York, where he led a series of jazz combos. He made an LP for Prestige with an organ trio (1964) and a reunion album with other Lionel Hampton alumni for the French label Black & White (1976). In the mid to late 1980s he led a quartet that played the Saturday afternoon "jazz brunch" at Sweet Basil in New York City. He died May 1, 1999 in a New York nursing home.

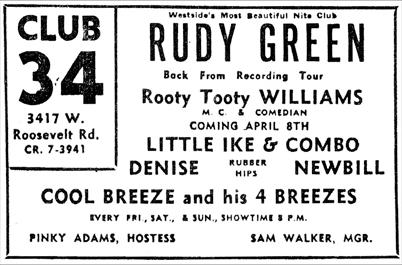

Rudolph Spencer Greene (often spelled "Green") was a blues guitarist and blues and ballad singer who first recorded for the Bullet label in Nashville, cutting two sessions as a leader in 1946 and 1947. He resurfaced on two sessions as a leader for Chance Records in 1952 and 1953. He also made as a sideman appearance in 1953, behind singer Bobby Prince for RCA Victor. Greene was a disciple of T-Bone Walker. One of the two photos we have seen of him shows him playing the guitar behind his head, a stunt for which his idol was well known—and many of the fine guitar solos in his recorded work show that fluid approach. Greene was continuously employed in the Chicago area clubs during 1954 and the first half of 1955. As late as January 1955 he was still being billed as a Chance recording star, while performing at Club 34 (3417 Roosevelt Road). After a couple of weeks at the Crown Propeller Lounge, he returned to Club 34, which declared in early April that he was "back from a recording tour." The "tour" hadn't taken him any farther away than Universal Recording, but no matter.

Greene sings "Highway No. 1" in a wailing Roy Brown style. Prince Cooper contributes some rolling piano. Greene solos in his best T-Bone manner, and Chamblee follows with a strong statement of his own. On "You Mean Everything to Me," Greene is supported by the redundant triplets of Prince Cooper and the wordless vocalizing of the Four Buddies. Chamblee weaves through the vocal sections and makes a convincing solo statement.

"Highway No. 1," says Dave Penny, was Club 51's biggest seller. The Billboard reviewer in the May 7, 1955 issue gave "Highway No. 1" a 68 and said it was "an appealing traveling blues based on traditional material... sung by a talented shouter and given a solid rhythm backing, this makes quite listenable wax". Regarding "You Mean Everything To Me," the reviewer gave it a 66 and described it as "a quiet, sentimental ballad in which Greene gets a tastefully harmonized backing from the Four Buddies. Two good sides that deserve wide exposure." The upper 60s ratings in Billboard are lower than average, but the trade journal rated records for commercial potential as well, and the reviewer knew that Club 51 was an exceedingly small label. Cash Box also reviewed the single in its May 7 issue (p. 24), giving both sides solid ratings.

Rudy Greene's run at Club 34 continued into May 1955. By late in the year or early in the next, he was back in Nashville recording for Excello. This was followed by sessions with Ember (in New York in 1957) and Poncello (in Nashville in 1961).

Our basic session information comes from Leadbitter and Slaven (1987), who give a 1955 date. However, we filled in the instrumental and vocal group personnel. Background on Greene (such as there is) was obtained from Dave Penny's fine profile of his work, "Rudy Green-The Blues Imitator," from Blues & Rhythm: The Gospel Truth, March 1989.

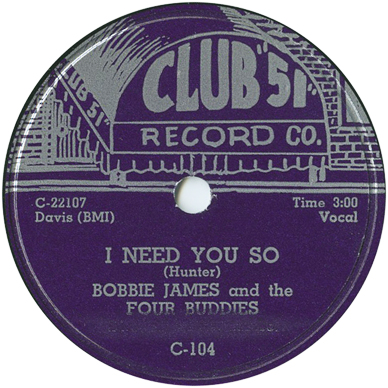

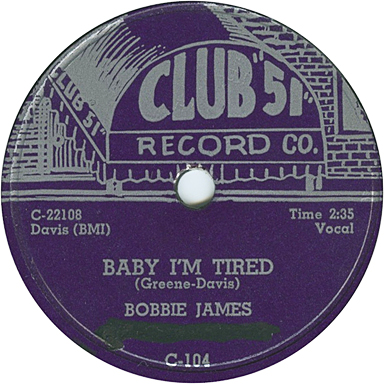

Bobbie James (voc) with the "Four" Buddies: Ularsee Manor, Jimmy Hawkins, Irving Hunter, William Bryant, and Dickie Umbra (voc on ^ only); accompanied by Eddie Chamblee Combo: Eddie Chamblee (ts); Robert "Prince" Cooper (p); Rudy Greene (eg); unidentified (b, d).

Universal Recording, Chicago, March 1955 (same session as Cl3)

| C-22107 | I Need You So^ (Hunter) | Club 51 104, Relic 5059 | |

| C-22108 | Baby I'm Tired (Greene-Davis) | Club 51 104 | |

| C-22108 [alt.] | Baby I'm Tired (Greene-Davis) | unissued |

Bobbie James was born Bobbie Mitchell and came from a prominent church family in Chicago. At age twelve, she began singing gospel in the New Covenant Baptist Church (44th and Langley), of which her grandfather was a well-known pastor. While still in high school she joined an R&B vocal group, the Five Jays, followed by a four year stint with the Goodie Watkins Band. According to Richard Reicheg, there was another singer named Bobby Mitchell who had already recorded, hence the name change.

In May 1955 in a McKie Fitzhugh-promoted show at the Park City Bowl, the Five Buddies appeared with Bobbie James (as "Bobbie James and her Buddies") along with Amos Milburn, the Danderliers, and the Clouds. This suggests that the James may have also been promoting her recent release on Club 51.

Cash Box (April 23, 1955, p. 24) gave both sides OK ratings. Regarding "Baby I'm Tired," the Billboard reviewer commented (in the May 7 issue), "The songstress expresses her disillusionment with men in this wailing blues. Her voice has a pleasing dark quality that seem cut out for this type of song" (rating 67). On "I Need You So," the verdict was, "Miss James brings out the sentiment of this ballad with believable emotion. Again her sobbing lower tones make an impression. With stronger material she could go far" (rating 64).

"I Need You So" is an excellent song, however, and features lovely support from the tenor sax and low-key humming by the Five Buddies. "Baby I'm Tired" is a routine twelve-bar blues, again with a nice sax break. There is a test pressing of this same performance of "Baby I'm Tired" on a Universal Recording acetate that was once in Jimmie Davis's holdings. Our label information is confirmed by a copy of Club 51 104 in the collection of Tom Kelly; the original label credits the Eddie Chamblee Combo.

Jimmie Davis decided to take the credit to Chamblee's group off the label. Some copies of Club 51 104 (e.g., one offered for sale in John Tefteller's auction of September 2009) have new labels without the Chamblee attribution; on a copy in Robert Campbell's collection, the attribution has been blacked out on one side—and removed with a pencil eraser on the other. Davis hadn't made a mistake: All four sides of Club 51 103 and 104 definitely have Eddie Chamblee on tenor sax. We figure that Chamblee's contract with United hadn't expired when the sessions were made, and Jimmie Davis did the erasing to avoid problems with Leonard Allen.

In December 1959, Bobbie James surfaced at McKie's Disc Jockey Lounge; a caption on a photo of Tom Archia and Lucius Washington, who were headlining at the club, stated "They will be joined by Bobbie James who will have charge of the vocals" (December 12, 1959, p. 18). James got a write-up in the March 3, 1960 Chicago Defender while still performing at McKie's (this is where we obtained our meager biographical information about her).

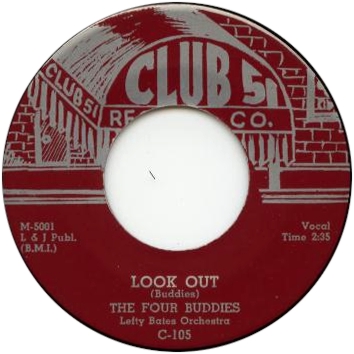

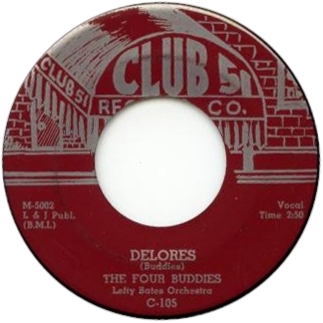

The "Four" Buddies: Ularsee Manor (lead), Jimmy Hawkins (alt lead), Irving Hunter, William Bryant, Dickie Umbra (voc); with Lefty Bates Orchestra: William "Lefty" Bates (eg); James "Red" Holloway (ts); Prince Cooper (p); poss. Quinn Wilson (b); poss. Paul Gusman (d).

Universal Recording, Chicago, 1955

| M-5001 | Look Out (Buddies) | Club 51 105, Relic 5059 | |

| M-5002 | Delores (Buddies) | Club 51 105, Relic 5059 | |

| M-5002 [alt.] | Delores (Buddies) | unissued |

Dickie Umbra says this was a later session than the one with Greene and James. The change to a new matrix series tends to confirm it.

The Five Buddies were formed in the Ida B. Wells housing project around 1952. The original group was called the Four Buddies and consisted of lead Ularsee Manor, tenor Jimmy Hawkins, tenor Nathaniel "Sam" Hawkins (Jimmy's cousin), and bass/baritone Willie Bryant. The addition later of baritone/bass Dickie Umbra made the group the Five Buddies. Most of the members attended Tilden Tech and Wendell Phillips high schools. Sam Hawkins was soon replaced by Donald Ventors, but when Ventors moved back to his home in Texas he was replaced by Irving Hunter.

In September 1954 the group got their break. They did a radio show with McKie Fitzhugh as part of the promotion for the deejay's big event at Corpus Christi Auditorium that featured a host of acts, including the Five Buddies and five other vocal groups. Davis saw the group and signed them up to his label.

Davis first used the Five Buddies as back-up session singers for Greene and James. The group's single was released, in either 1955 or 1956, but to no obvious acclaim. "Delores," the ballad side, features lovely sax work that weaves throughout the song and also unusually extended melodic sax solo. Richard Reicheg reports an alternate take of "Delores" on a Universal Recording acetate. On the jump side, "Look Out," the sax man wails a few measures. In addition to the regular release of Club 51 105, some D J copies of the 78 were issued with typed-in label copy but on regular pressings, not lacquers; one of these is in the collection of George Paulus. We should further note that "repro" 45s of Club 51 105 are in circulation among doowop collectors; thanks to Armin Büttner for alerting us to these.

By this time Eddie Chamblee was no longer available. Ularsee Manor identifies the tenor saxophonist as Red Holloway (who can be heard weaving his sax through vocal group ballads on many sessions from the period) and the pianist as Prince Cooper.

James "Red" Holloway was born May 31, 1927 in Helena, Arkansas. He was raised in Chicago, where his family moved when he was 5, and attended DuSable High School. He began on piano, but took up saxophone in 1942. In 1943, he became a member of the first edition of Gene Wright's Dukes of Swing; in 1946 he joined the Army. Upon his discharge, he attended the Chicago Conservatory of Music while playing with the Jump Jackson band. During the 1950s Holloway led bands at Club Evergreen, the Crown Propeller Lounge, Stage Lounge, and Roberts Show Lounge, among others.

Holloway became a regular on the studio scene in October 1952, when he accompanied singer Big Bertha Henderson for Chance in a studio band led by Al Smith. He did studio work for Chance in other Smith-led bands, as well as with his own quartet. He soon became one of the top R&B studio musicians in town, laying down session after session for Vee-Jay, United/States, and Chess, as well as tiny labels like Club 51 and Theron. He also recorded as a leader for Mercury (1956, never released) and Tommy Jones' Mad label (1958 or 1959).

In the 1960s Holloway spent much of his time on the road with the Lloyd Price, Bill Doggett, and Jack McDuff bands. In 1967, he moved to Los Angeles, then in 1987 to Cambria, California. In his later years, Holloway recorded as a jazz artist, beginning with 4 LPs done in the New York area for the Prestige label from 1963 through 1965. Still active in music past the age of 80, Red Holloway died in Morro Bay, California, on February 25, 2012, after suffering a stroke and kidney failure.

We drew in part on the obituary by Howard Reich in the Chicago Tribune, February 26, 2012 (http://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/music/ct-nw-red-holloway-obit-0226-20120227,0,3005292.column).

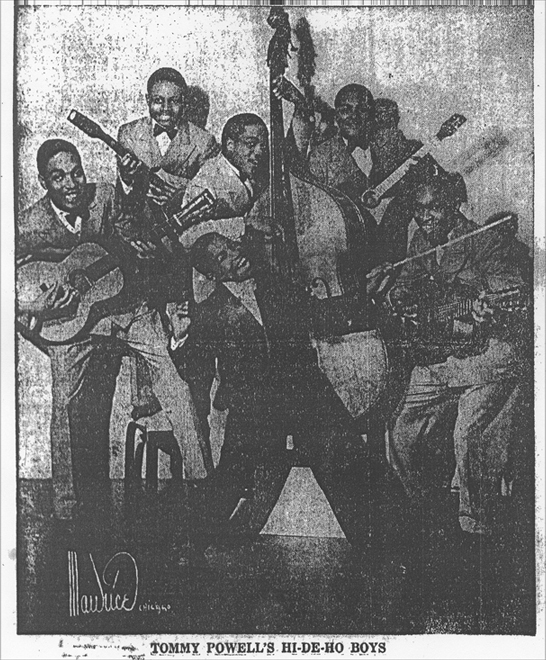

William "Lefty" Bates was born in Leighton, Alabama, March 9, 1920. He was raised in Saint Louis and went to Vashon High School. While still in secondary school Bates formed a vocal/string band, a kind of ensemble that was extremely popular in the black community during the 1930s and the 1940s. The group was called the Hi-De-Ho Boys, and consisted of Tommy Powell (dance / vocals), James Crosby (bass / vocals), Lefty Bates (guitar / vocals), Bill Williams (guitar / vocals), Walter Jones (guitar / vocals), and Cleo Roberts (guitar /vocals). The Hi-De-Ho Boys moved to Chicago in 1936, recorded on Decca, and became a semi-regular act at the Club DeLisa from 1937 to 1950.

Bates had to leave the Hi-De-Ho Boys to serve in World War II. When he got out he first formed a combo of his own, which played the Three Deuces in February 1946. He then joined the Aristo-Kats, who successfully recorded two sessions for RCA Victor in 1946 and 1947. The members besides Bates were Orlando Randolph (trumpet/vocals), Quinn Wilson (bass), and Julius Wright (piano). When the Kats broke up in 1948, Bates rejoined the Hi-De-Ho Boys. The group's last engagement at the Club DeLisa ended in early May 1950. In a demonstration of changing tastes, the Boys were replaced for a couple of weeks by another vocal-string ensemble, then organist Lonnie Simmons moved in and the Club DeLisa never hired another such group. Shortly before the group's run at the Club DeLisa ended, the Hi-De-Ho Boys cut two sides for Mayo Williams' Harlem label.

In 1952 Bates put together a trio with Quinn Wilson (bass), and Horace Palm (piano), playing regularly with this lineup for the rest of the decade (sometimes a horn player was added to make it a quartet). The Bates combo could be heard in such establishments as Duke Slater's Vincennes Lounge (601 East 36th), the Shalimar Club (5659 Wentworth), Banks' Trocadero Lounge (4719 Indiana), and Spruce's Duck Inn Lounge (5550 South State). When Bates got the call for a studio session, he often brought Palm and Wilson along.

Bates recorded minimally under his own name, producing one release on Boxer (1955), one on United (1957), a session on Tommy Jones' Mad label (1958), and two on Apex (1959). Though none of the sides achieved any kind of traction, it is unlikely that Bates cared. He earned his money in club gigs and as the most in-demand guitar player for recording sessions; beginning with Chance in 1952, he laid down countless sessions for Vee-Jay, but also did work for much smaller operations like Club 51. Bates's last musical affiliation was with the Ink Spots, during the 1970s. Because of the onset of Alzheimer's disease, Lefty Bates had to go into a nursing home in 2001. He died on April 7, 2007.

In a typical Lefty Bates studio band, Quinn Wilson and Paul Gusman were likely choices on bass and drums; however, Prince Cooper's associates might have been called on instead.

A demo of the Five Buddies singing "Delores" survives (issued on the same Relic LP), and it has a similar instrumental lineup to the official master.

In 1957, the Five Buddies broke up, as the big break the group was looking still appeared all too elusive. Curiously, while the group went by the name Five Buddies, Davis always listed them as the Four Buddies. It's been suggested that Davis did this to sow confusion with deejays who were a lot more likely to know an East Coast group, the Four Buddies, who recorded on Savoy. Information on the "Four" Buddies came from our interviews with Ularsee Manor and Jimmy Hawkins, plus David Hinckley and Marv Goldberg's article on the group, "The Other Four Buddies," which appeared in Goldmine, April 1979.

Willie McNeal (voc); other musicians unidentified.

Chicago, 1955

| Things Ain't What They Used to Be | Club 51 C106 (unreleased lacquer), St. George LP 103 | ||

| Streamline Woman | Club 51 C106 (unreleased lacquer), St. George LP 103 |

A letter from Bill Greensmith to Blues & Rhythm #45 describes this Club 51 "metal dub" with the purple-on-white stick-on label carrying some typed information. The artist was Willie McNeal and the titles were "Things Ain't What They Used to Be" b/w "Streamline Woman." These two titles were eventually issued on a St. George LP (STG 1003) titled Southside Screamers Chicago 1948-58. St. George listed the artist as The Boll Weavil Blues Trio; according to Greensmith, "it is thought that McNeal is the same artist as Boll Weavil from the Ora Nelle sides on the Chicago Boogie LP (Barrelhouse BH04)."

More we cannot say, as Jimmie Davis dropped his plan to release McNeal's sides and reassigned C106 to his Sunnyland Slim single.

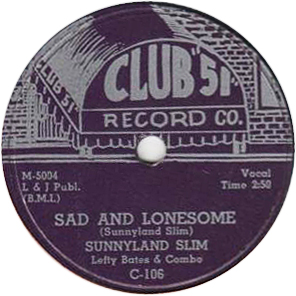

Sunnyland Slim (voc, p); with Lefty Bates Combo: Lefty Bates (eg); Red Holloway (ts); Louis Myers (eg); unidentified (b); unidentified (d).

prob. Universal Recording, Chicago, 1955

| M-5003 | Be Mine Alone (Slim) [SS, ens voc] | Club 51 106, Classics 5171 [CD] | |

| M-5004 | Sad and Lonesome (Slim) [SS voc] | Club 51 106, Classics 5171 [CD] |

Sunnyland Slim (born Albert Luandrew, 1906 - 1995) was the most durable of all the Chicago bluesmen. He began recording in Chicago as a sideman in 1946. His first sessions as a leader were for Hy-Tone and Aristocrat (both sessions in September 1947--apparently just a few days apart--and both followed up for the same labels in December). He subsequently picked up with RCA Victor (as Dr. Clayton's Buddy), Opera, Mercury, and Tempo-Tone. In the early 1950s he cut for his own Sunny label (1950), for Regal (1951), and for Mercury again (also 1951). And he was prolifically recorded by JOB during its most active period (he probably owned a stake in the label, where he participated in a session in 1949 [his own sides were sold to Apollo], probably one in 1950, four sessions in 1951, four in 1952, two in 1953, and two in 1954). Records also appeared on Blue Lake (1954) and he made sides for Vee-Jay (also 1954) that took 52 years to finally see release. By 1955, he seems to have parted company with Joe Brown and JOB, which let Jimmie Davis jump in.

The session details are from Leadbitter, Fancourt, and Pelletier (1994), who give a firm 1955 date.

Made during a period when Sunnyland Slim was turning out a lot of routine performances, the Club 51 sides are exemplary. "Be Mine Alone" is a vigorous jump tune; Sunnyland wails the lyrics to this 12-bar blues with élan over a swinging unit that has Red Holloway blowing up a storm on his long solo. Holloway's responsive phrases to Slim's lyrics on the last third of the song are particularly effective. "Sad and Lonesome" is a particularly exuberant slow blues that has Slim getting nice counterpoints from Louis Myers, whose energetic solo exhibits the virtues of blues records of the period with its hot, deliberately distorted sound. (We previously thought this might be Lefty Bates exercising his rock and roll chops, but as Dick Shurman points out, Sunnyland shouts "Ride, Louis, ride!") These sides were reissued for the first time in 2006 on Classics 5171, Sunnyland Slim 1952-1955, which also includes Sunnyland's previously unissued Vee-Jay sides.

After his Club 51 session, Sunnyland Slim experienced the only significant recording drought since he had begun making records; he couldn't find another small company willing to issue his work on singles. After picking up a little sideman work for Abco (1956) and one session for Cobra (also 1956), he would not resume his recording activity until the early 1960s, as the blues revival kicked in.

Club 51 considered releasing another record on Prince Cooper, who remained active in Chicago-area clubs, sometimes with a trio and sometimes with a quartet. "Blues at the Capri" is a significant jazz performance by a trio. It runs 7 1/2 minutes and takes up both sides of a 10-inch 78.

Robert "Prince" Cooper (p); unidentified (eg); unidentified (b).

prob. club recording, Chicago, 1956

| Blues at the Capri Part 1 | Club 51 C107 (unreleased lacquer) | ||

| Blues at the Capri Part 2 | Club 51 C107 (unreleased lacquer) |

These two sides were given a tentative release number (C107) and limited circulation on lacquers with typed labels of the "Disc Jockey Advanced Sample" variety. They were professionally recorded, probably in a club instead of a studio. Whether Prince Cooper had a gig at a club called the Capri is still being researched.

There is first-rate solo work by all three participants on "Blues at the Capri." Had it been released, it would have solidified Prince Cooper's reputation as a jazz performer and Club 51's as a jazz label. Instead, Jimmie Davis changed his plans, reassigning 107 to Honey Brown's R&B release.

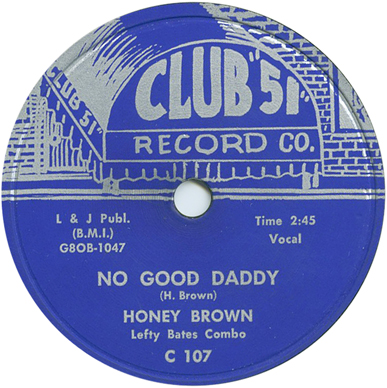

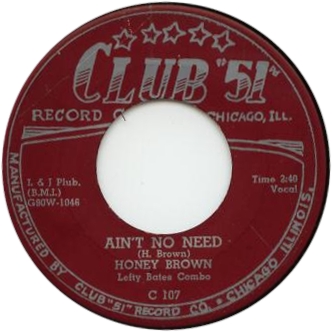

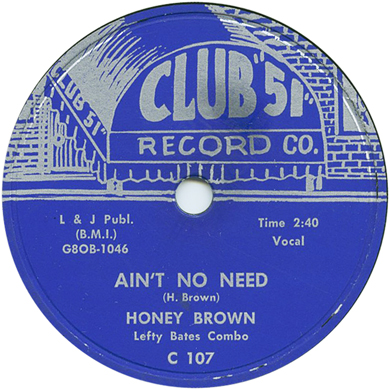

Honey Brown (voc); with Lefty Bates Combo: Lefty Bates (eg); Red Holloway (ts); McKinley Easton (bars); prob. Horace Palm (p); prob. Quinn Wilson (b); prob. Paul Gusman (d).

Chicago, 1956

| 1215 G9OW-1047 G8OB-1047 |

No Good Daddy (H. Brown) | Club 51 107 | |

| 1216 G9OW-1046 G8OB-1046 |

Ain't No Need (H. Brown) | Club 51 107 |

This release carries two matrix numbers, one from the studio where it was recorded (1215 and 1216) and one from RCA Victor, which did the mastering and pressing (the G8OB prefix appears on the 78s, and the G9OW on the 45s).

Honey Brown first surfaced in 1937, when her photo ran in the Chicago Defender on February 27 (she appeared to be in her early 20s then); at the time the "charming and original Honey Brown of Chicago" was performing in Toledo, Ohio. She was back in Chicago in June of 1937, performing at the Swingland (343 East Garfield); the Defender described her as a song and dance act.

Brown made her way to Detroit by the early 1940s, and throughout much of the decade worked in the city's clubs as a blues singer. When she appeared at Club B & C, in the legendary Paradise Valley section of Detroit, the Michigan Chronicle reported that Brown was "singing blues, and how." In 1944, she appeared at Lee's Sensation. The paper reported a long gig during December 1945 and January 1946 at the Club Owens, commenting, "Honey Brown, the gal that 'rocks' the blues, headlines... delivery of 'Salty Papa' and 'St. Louis' were encore numbers. Her reception proves that local theatre bar patrons know a good blues singer when they see one." Regarding a Brown date at the Blue Bird Inn in July 1947, the Chronicle exclaimed, "Honey Brown, the girl with a voice that drips like honey, sings blues that really sting..."

In the late 1940s, Brown began switching back and forth between her hometown of Chicago and her adopted town of Detroit. She reappeared in Chicago in August 1948 as part of a revue at the Club DeLisa (5521 South State), and then in October 1953 at the Crown Propeller Lounge (868 East 63rd). Brown was in Detroit in June of 1954, playing at El Sino and the famed Twenty Grand. By 1956, she was in Chicago recording for Club 51.

The Club 51 session was her second appearance on vinyl—her first had been four sides in 1950 for the New York-based Derby label, two with the Freddie Mitchell Orchestra and two with the Edward Johnson Orchestra. Our basic session details are from Leadbitter and Slaven (1987), who give a 1955 date. However, the RCA Victor-derived matrix numbers, with the G prefixes, point to 1956. The non-Victor matrix numbers may be from the same 1200 series used by Ronel for some of its singles and by Ping for its last two releases. In fact, Ronel 109, a Country release by Tiny Murphy, carried matrix numbers 1213 and 1214; it, too, was pressed by RCA Victor in 1956. The studio may have been MBS.

On Club 51 107, we hear Red Holloway on tenor sax and Mac Easton on baritone sax. The rhythm section sounds like Lefty's frequent associates Horace Palm and Quinn Wilson, with Paul Gusman (who worked a lot of recording sessions with Lefty) on drums. Further confirmation: Red Holloway told Dani Gugolz that he was on the record. Leadbitter and Slaven identified only Lefty Bates on guitar.

Typically, Honey Brown's Club 51 single features a ballad side and a jump side. "No Good Daddy" is a slow uptown blues. Brown’s strongly etched voice smolders over an accompaniment by a wonderful tickling piano (we think it's Horace Palm) and Lefty Bates' guitar, while Red Holloway blows a long solo working the lower parts of his B-flat tenor with smooth authority. "Ain’t No Need" is the jump side and it swings with vigor, as Brown rides the rhythm section with assurance, while Holloway blows on the short break and Mac Easton on baritone sax plays some prominent counterpoint. It seems inconceivable today that these terrific sides were virtually ignored upon their release in 1956. There has never been a legitimate release of the Honey Brown single, but "repros" on 45 rpm are now widely available.

Up to this point, Club 51 had used the same design, depicting the brick front wall and the big awning of its mythical namesake, on all of its labels (first in purple on white, then in silver on red or purple). For some reason the company tried a different label design, on 107 only. This didn't last, however. Other copies of 107 reverted to the awning design (now on a blue background). The blue awning label was then used exclusively for Club 51's final release, on 108.

On June 8, 1957, Cash Box (p. 36), in its Los Angeles notes, reported that John Barnette had been to Chicago to sign Honey Brown to a recording contract. A session in Hollywood was said to be imminent. There was no mention of the label that Barnette, a well-known agent, was involved with. There was a reason for this. Some of Barnette's previous attempts to get Chicago-based artists (e.g., Ann Carter) recording sessions in Los Angeles had fallen through. We suspect the same thing happened in this case. In any event, Honey Brown's contract with Club 51 had expired.

Brown by the late 1950s had settled down in Chicago, and continued to make occasional club appearances, including one on the undercard for a Roy Milton date at the Crown Propeller Lounge, which was then on the way down, in January 1959. Brown recorded one further session that we know of, for Tommy "Madman" Jones's M&M imprint, in 1961.

Sources on Brown: Chicago Defender clips: 26 June 1937, 27 February 1937, 7 August-3 September 1948, 24 September 1953, 3 January 1959; and courtesy of Lars Bjorn, co-author with Jim Gallert of Before Motown: A History of Jazz in Detroit 1920-1960 (University of Michigan Press, 2001), Michigan Chronicle clips: 31 January 1942, 15 December 1945, 5 January 1946, 26 July 1947, and 5 June 1954.

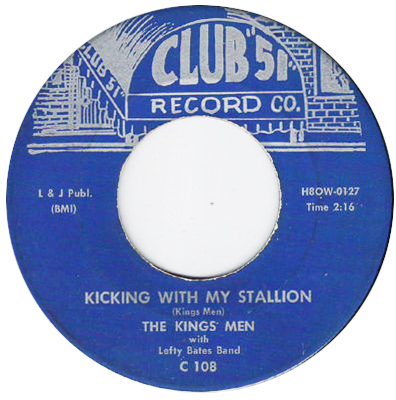

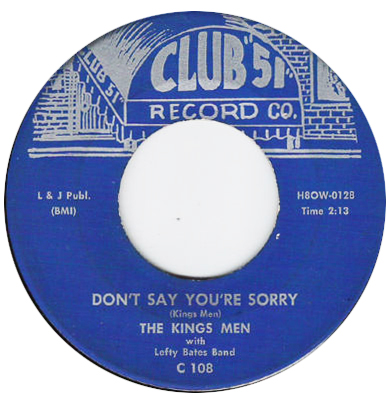

The Kings Men: Eugene Smith, Walter Broad, Herman Nolan, Johnson Williams, Mickey Green (voc); with Lefty Bates Band: Lefty Bates (eg, dir); Lucius "Little Wash" Washington (ts); McKinley "Mac" Easton (bars -1); Horace Palm (p); Quinn Wilson (b); prob. Al Duncan (d).

prob. RCA Studios, Chicago, early 1957

| H8OW-0127 H8OB-0127 |

Kicking with My Stallion -1 (Kings Men) | Club 51 108, Relic 5059 | |

| H8OW-0128 H8OB-0128 |

Don't Say You're Sorry (Smith-Twiggs) | Club 51 108, Relic 5059 |

The Kings Men, formed in 1954 while they were still students at Englewood High, joined Club 51 in 1956. The original members were Johnson Williams, Eugene Smith, Walter Broad, Ron Henderson, and Billy Hebert, but by the time the group recorded the group had lost Hebert and Henderson to the draft, to be replaced by Herman Nolan and Mickey Green.

One member of the group recalls hearing the record on radio in November 1956, but a release date in March 1957 is consistent with their first appearance at a well-advertised package show—and with the RCA Victor-applied matrix numbers (H8OB appears on the 78 rpm release, and H8OW on the 45). "Don't Say You're Sorry," the ballad side, features a true lead singer with unusually pleasing voice. No room is given for any of the musicians to show their stuff. This number has been credited to Smith and Twiggs on the reissue; the original labels give the group the composer credit. "Kicking with My Stallion" uses a common melody that appeared in many routine Chicago jumps; only the words are changed. There's room for the sax to wail on a solo break. The tenor saxophonist sounds like Little Wash, and the rest of combo appears to consist of Lefty's usual associates in the studio.

Lucius Washington was born in Memphis, Tennessee, on June 18, 1926. He began on guitar but soon moved to the tenor saxophone. In 1942, frustrated by the lack of music schools in Memphis, Washington moved to Chicago, where he stayed with a cousin and finished high school at Wendell Phillips. He served in the armed forces in 1944-45, then returned to Chicago where he attended Metropolitan School of Music. In 1949, he started his own group with help from drummer and bandleader Jump Jackson. In an interview with Robert Campbell (18 July 2001), he recalled that "Little Wash" was his hasty suggestion for a marquee name when Jackson was assembling promotional material for the group. He later regretted the choice, because he considered himself a jazz musician and his handle made fans think he was a bluesman.

Washington really established himself playing weekends at Ada’s Chicken Shack (5114 South Prairie) with a "battle of the saxes" format that included Grady Johnson (tenor sax), Louis Carpenter (piano), and Walter Perkins (drums). Contracts filed with Musicians Union Local 208 indicate that his group was in residence at Ada’s from May 1952 through the beginning of 1954.

Thereafter, Little Wash led bands at the Victory Club, the Cotton Club, the State Theatre Lounge, the Crown Propeller Lounge, the Stage Lounge, the Pit, and the Strand Show Lounge (where he was working at the beginning of 1956). Washington got a major break when Al Smith, who had been heavily reliant on Red Holloway for tenor sax work, was looking for a "new sound" on some of his studio sessions, and Lefty Bates recommended him. Lucius Washington appeared on something like 20 studio sessions for Vee-Jay between May 1956 and May 1958, backing singers and vocal groups; he also participated in two for States (1956) and this lone session for Club 51. He also got a lone session as a leader, probably in 1957, for a label called PMS.

From 1957 to 1959, Washington held down a high-profile engagement at McKie's Disc Jockey Lounge, in a battle of the saxes format with Tom Archia; McKie Fitzhugh broadcast parts of the proceedings on his radio show. He cut a local LP in 1969 in a group under the leadership of drummer Billy Mitchell. Lucius Washington's last regular gig was at the Downtown Marriott Hotel in Chicago, in a trio led by pianist Laura Hoffman, from 1989 through 1999. When the gig ended, Lucius Washington retired.

Billboard reviewed the Kings Men disc in the April 20 issue. The reviewer was most impressed by the "Kicking with My Stallion" side, giving it a 68 rating, and saying, "Interesting story told here about a horseback ride with a chick. Material has a new slant and the group gives it a good ride. Plenty is happening here and the side is worth a look from jocks." "Don't Say You're Sorry" got a 60 rating. The reviewer panned it as follows, "Okay r&b ballad gets a big sound from the group. There's little, however, to make it memorable in a world of many new releases. Rough sledding ahead."

According to Robert Ferlingere there are "repro" versions of this 45 on red and black vinyl.

In March 1957, the Kings Men appeared at the Grand Ballroom on a Herb Kent-sponsored show that included the Spaniels, Dream Kings, bluesman J.B. Lenoir, and the Willie Dixon Orchestra. The concert was a great way to kick off their recording career. In April, the group appeared at Herb Kent's spectacular concert at Hyde Park High and shared the stage with the Danderliers, Moroccos, Debonairs, Debs, Dells, Magnificents, and Dee Clark, among others. Presumably it was downhill for the group after that.

We obtained our basic history on the Kings Men from Echoes of the Past #51 (2000), Mitch Rosalsky's article "The Kings Men," based on interviews with Billy Hebert and Herman Nolan. We identified the accompanists (except, of course, for Lefty Bates) by ear.

The label closed down before the end of 1957. This was the first indication that the Davises' entertainment complex was on the decline. In 1958, they shuttered the Savoy Record Mart and their beloved Park City Bowl was forced to close. The following year Jimmie Davis opened up a rink called the Savoy at 61st and Cottage Grove. For a time the rink maintained a standing agreement with Musicians Union Local 208, which permitted the establishment to hire bands for one-nighters. On May 21, 1959, the Local 208 Board meeting minutes (p. 1) stated that a one-year agreement with the "Savoy 51 Skating Rink" had been accepted and filed. On January 18, 1962, the establishment was identified as the "Savoy '51' Roller Rink" on Local 208's list of one-year agreements (it reappeared under the same name when a new one-year agreement was posted on April 4, 1963).

As the neighborhood's center of gravity shifted southward, the rink relocated to 78th and Cottage Grove in 1963; it appears that the Davises no longer booked live music after the end of that year. When interviewed by the Chicago Sun-Times in 1987, Davis was operating the Savoy Skate Shop at 621 East 79th Street and a record shop next door. According to Herman Roberts (one-time proprietor of Roberts Show Lounge), Davis closed his skate shop in 1992. Jimmie Davis died in 1995.

There has never been a compete reissue of Club 51's output. Relic put out an LP, The Golden Groups—Part 35: The Best of Club 51 Records in the late 1980s; including it in the "Golden Groups" series entailed a focus on doowop. This is the music that built Relic, but the company was forced to fill out the LP with audition demos, most of them in truly miserable sonics. In retrospect, it might have been wiser to use the releases by Prince Cooper, Sunnyland Slim, and Honey Brown, plus the Bobbie James and Rudy Greene solo sides. That would have made a fabulous collector’s item. (The Sunnyland Slim sides were eventually reissued on Classics, but to this day nothing has been done with the other material.) Although Relic Records no longer exists, the former owners still currently hold rights to the label.

We've made no attempt to list all of the direct-to-78 demos that Davis cut in the back of his store, or the audition disks and tapes that other singers and groups presented to Club 51 and that Jimmie Davis kept. (However, a demo that Sun Ra cut with members of his first Arkestra, in the fall of 1955, and gave to Davis is covered on our Sun Ra page. For demos cut by Von Freeman's group, see our Parrot/Blue Lake page; for a King Fleming demo, see our King Fleming page.) There were a lot of demos, most not intended for use on the label, and the surviving items usually have no artist information attached (some vocal group demos and lacquers were loaned to Relic Records by Richard Reicheg and used to fill out Relic LP 5059). Besides, the recording quality is frequently dire; many of the demos were amateurishly recorded in clubs and practice rooms on less than the best equipment.

Jimmie Davis maintained some interest in gospel, as the abortive venture with the Highway Travelers indicates. A gospel acetate on Club 51 by another gospel group, The Spitual Voices (we're pretty sure that this was a misprint for Spiritual Voices, on labels that also misspell "Promised") was in Bill Sabis's collection. The record carried a stick-on Club 51 label (purple on white), marked as an advance sample for disc jockeys. However, there is no matrix number on either "The Promise Land" [sic] or "The Canyon Land," nor is there a tentative release number. We'll assume that the use of the Club 51 stick-on label without a release number indicated a lesser degree of commitment from the company. A track by at least one other (unidentified) gospel group, a brilliant performance of "God Made the World," was also included among the demos and test pressings once held by Jimmie Davis.

In developing the history of Jimmie Davis and his Club 51 operation we found the following particularly helpful: Donn Fileti's notes to The Golden Groups—Part 35: The Best of Club 51 Records (Relic 5059) which were based, in turn, on Richard Reicheg's interviews with Jimmie and Lillian Davis; and Delia O'Hara's Davis profile for the April 29, 1987 Chicago Sun-Times called "Skating through the Color Barrier." Robert Ferlingere's tutorials on the RCA Victor matrix number system helped us figure out the dates of label's last two releases. We also thank George Nettleson for providing the Kansas City Call clip that allowed us to firmly date the founding of Club 51; to Jerry Sko, Tom Kelly, Big Joe Louis, George Paulus, Dr. Robert Stallworth, and Dan Ferone for label photos (any Club 51 is extremely difficult to find in the collectors' market); to Richard Reicheg for a dub of Club 51 106; to Bill Sabis for a photo of the unreleased Club 51 102 and to Bill Greensmith, Stephen Dikovics, and Bo Sandell, and Richard Reicheg for information about the Club 51 penumbra--the array of lacquers, test pressings, and limited-circulation items that may have been intended for general release at one time.